In 1943, the Soviets and Germans unleashed some 7,000 tanks and 2.6 million men against each other on the steppes of central Russia. What was at stake? Everything.

German infantryman Raimund Rüffer would never forget the first day of Hitler’s offensive toward the Russian city of Kursk. The 20-year-old lieutenant struggled toward his platoon’s objective on the morning of July 5, 1943, against a weight of fire he had never before experienced. As he recalled many years later:

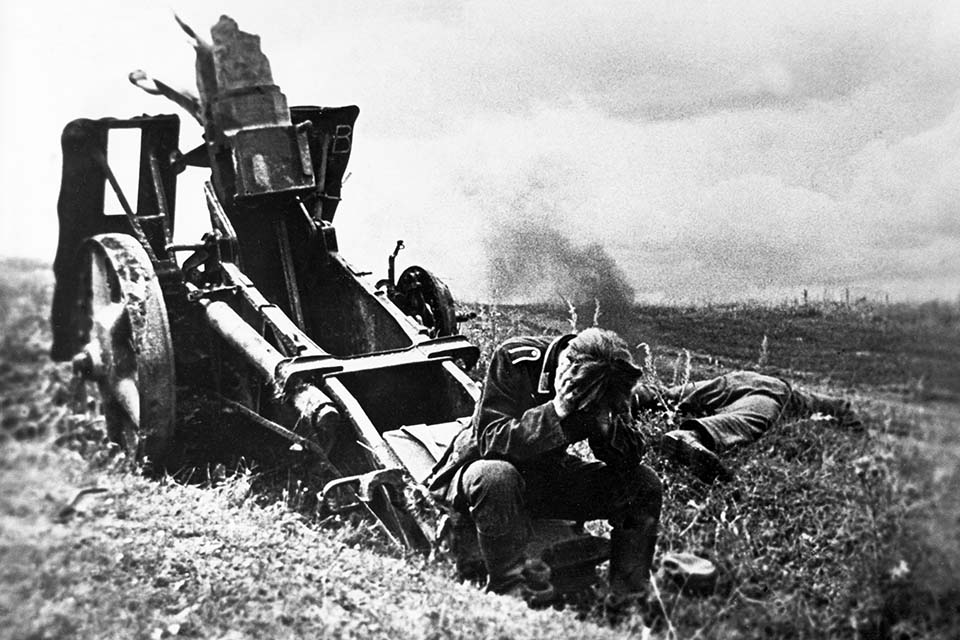

Ivan bullets zipped around us; I could hear them flying past my ears. I expected to be cut down any moment or blown to smithereens by the shells that slammed about….I heard my old friend Ernst panting seconds before his right arm was torn from his body by an explosion that flung his rifle at my feet. He whimpered as I moved toward him, but was silent by the time that I was at his side. A movement to my right. I twisted to see a camouflaged cover being thrown off a trench. I instinctively yelled a warning, dropped to one knee and squeezed the trigger of my rifle. The butt kicked and a round was sent hurtling toward a faceless Soviet soldier. In that same instant I was knocked off my feet as though hit by a heavyweight boxer. A Soviet round had struck me in the shoulder, shattering the bone and leaving me gasping for air.

At the battle’s conclusion, Germany’s inspector-general of armored troops, the wily Heinz Guderian, deemed that Germany had “suffered a decisive defeat”—certainly not the outcome Hitler had in mind when he said that Operation Citadel, as the Germans called the offensive, would be “of decisive importance.”

Yet the Battle of Kursk remains controversial, with aspects of its conception, conduct, and impact still hotly debated. For decades the battle has been visible only through two distorting prisms—one held by a defeated and divided Germany, and the other by the manipulative and oppressive Soviet regime. Only recently has a clearer and more balanced perspective come into view. It reveals Kursk as a desperate gamble by Hitler to secure the future of his forces on the Eastern Front—and even Germany’s wider prospects in the war. The struggle it spawned was staggering in its scope and consequence.

The roots of the Wehrmacht’s failure at Kursk are found not only in the battlefield’s dark Russian soil, but deeply buried in the stony ground of two years of fighting on the Eastern Front. Germany’s intense campaigning in the Soviet Union had damaged its ability to wage war successfully. By failing to overcome the Red Army in 1941 when the Wehrmacht was halted at the gates of Moscow, Hitler was bounced into a protracted, attritional war for which his country was neither mentally nor physically prepared.

During 1941, the poorly primed Soviets struggled to cope with their enemy’s onslaught. But German strategic and operational frailties, together with Stalin’s defensive tenacity and organizational prowess, gave Moscow the time it needed to bolster the nation’s defenses. By the end of 1942, with Hitler having massively extended the fighting front as he reached down into the Caucasus for oil, the Germans were struggling to keep pace with the demands of their unraveling campaign. The Soviets, meanwhile, worked assiduously to regain their poise and developed a strategy based on their strengths: the Soviet Union would wear down the Wehrmacht in the field as it mobilized its resources, reformed its armed forces, and gradually rolled out offensive fighting methods it had developed during the 1930s.

The application of the doctrine was seen in embryonic form during November 1942, when the Russians encircled the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, and then during several back-to-back operational victories the following winter, when the Red Army advanced 435 miles across a 750-mile front in southern Russia.

Although Soviet overambition eventually gave German Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, the commander of Army Group South, the opportunity to deliver a brilliant counterattack in February and March 1943 and capture the city of Kharkov to the south of Kursk, the Germans failed to retake Kursk and left an immense bulge, or salient, in the Soviet line surrounding that city.

Exhausted by their recent exertions, the Germans put offensive operations on hiatus while the high command decided what to do next, husbanded their assets, and waited for the ground to dry out after the spring thaw.

Although German resources were stretched to the breaking point, Berlin was determined to regain the initiative on the Eastern Front, and the führer was immediately tempted by a plan to take Kursk when Manstein presented it to him in early March. The bulge had a frontage of 250 miles, requiring the Red Army to commit nine valuable armies to its defense. If the Wehrmacht could go on the offensive and nip it out with thrusts from the north and south, it could reignite the Supreme Command’s offensive ambitions. Hitler backed the plan with considerable enthusiasm.

“We must prepare diligently but with discretion and ensure that the best formations, weapons and leaders are positioned at the points of main effort with access to plentiful supplies of ammunition,” the führer announced. “Every officer and every man must recognize the significance of this attack. Victory at Kursk must serve as a beacon to the world.” He directed that the offensive be launched in late spring.

The Soviets, meanwhile, pondered their own options in light of intelligence reports that the Germans were preparing an attack into the salient. Against his instinct—but revealing a growing maturity within the Soviet high command—Stalin acceded to arguments that the Red Army should defend Kursk rather than launch an offensive in the area.

The architect of the Soviet strategy, Red Army commander Georgy Zhukov, later wrote that the objective was “to wear down the enemy on our defense, destroy his tanks, and then, throwing in fresh reserves we go over to a general offensive and decisively defeat the basic concentration of the enemy.”

As the Soviets prepared for battle, detailed intelligence flowed in about the coming German offensive—aside from the actual start date. This was at least partly due to the operation’s repeated postponement by Hitler, who was increasingly concerned by his enemy’s numerical superiority. In the end he could do little but hope to counter it with the Wehrmacht’s skill, professionalism, and advanced weaponry. Indeed, he placed such faith in the new Panther medium tank that despite disquiet about its mechanical reliability and a distinct lack of crew training, he tied Operation Citadel’s launch date to the tank’s arrival at the front.

Guderian, aghast at the decision and convinced that the offensive was a grave mistake, confronted Hitler with his fears on May 10. “Do you believe, my führer,” Guderian began, “that anyone even knows where Kursk is…? Why do you want to attack in the east, particularly this year?” Hitler’s reply was disturbing: “You are quite right. The thought of this attack makes my stomach queasy.”

The goals of Operation Citadel were subsequently downsized, with the original aim of providing a springboard from which the Wehrmacht could re-launch its offensive action in the East dropped as too ambitious given the available resources. In its place came the far more modest aim of shortening the front and inflicting enough damage on the Soviet armored forces to allow the Wehrmacht to temporarily withdraw its panzers to deal with the growing Allied threat in the Mediterranean. Under these circumstances—and with the delivery of the Panthers significantly delayed—Hitler did not set the date of Citadel’s launch until July 1, with the offensive to begin four days later.

The attacking German force consisted of a total of 777,000 men, 2,451 tanks and assault guns (70 percent of German armor on the Eastern Front), and 7,417 guns and mortars. The plan was for Colonel General Walter Model’s Ninth Army, positioned about 50 miles north of Kursk, to break the Soviet defenses with infantry and artillery, then exploit their expected success by drip feeding armored formations into battle. Meanwhile, 65 miles south of Kursk, Colonel General Hermann Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army—a formation of nearly double Model’s armored strength—intended to crack the Red Army with a full-blooded panzer thrust from the outset. The Germans aimed to reach Kursk within a week, 10 days at the most: any longer was considered likely to give the Soviets the opportunity to grind the attack down, inflict heavy losses, and launch counterattacks.

Opposing them was General Konstantin Rokossovsky’s Central Front in the north, and General Nikolai Vatutin’s Voronezh Front (named for a region south of Moscow) in the south. The Red Army’s meticulous defenses were 70 miles deep, with fallback positions up to 175 miles behind the salient. They were specifically designed to catch and stop Germany’s blitzkrieg: A curtain of fire would slow the attacking formations, and then a series of battlefield obstacles—including nearly a million antitank and antipersonnel mines, antitank resistance points, riflemen, machine gun nests, barbed wire, and dug-in armor—would undermine their momentum. Their intention was for the Germans to struggle to achieve even a modicum of mobility within this so-called “defensive zone.” When they were exhausted, Colonel General Ivan Konev’s Steppe Front, positioned more than 200 miles to the east and well placed to halt any German breakthrough, would counterattack.

In total the Soviet forces at Kursk amounted to 1,910,361 men, 5,128 tanks and self-propelled guns, 31,415 guns and mortars, and 3,549 aircraft. The combined strength of the Central and Voronezh Fronts alone was 1,337,166 men—and they also had twice the number of tanks and aircraft as the Germans, and four times the artillery.

As dawn broke on July 5, the men of II SS Panzer Corps were in a positive mood. Tiger radio operator Wilhelm Roes, for example, thought, “Nobody will be able to resist this might,” and later explained: “We were so confident of winning, as we had always done before. It was a dead certainty for all of us.”

Hermann Hoth expected his Fourth Panzer Army to break the first two lines of Soviet defense within 24 hours and to have crumpled the third and advanced halfway to Kursk within 48 hours. He was to be disappointed. XLVIII Panzer Corps’ Grossdeutschland Panzer Grenadier Division, for example, immediately ran into difficulties that first morning. Its left flank became entangled in a thick Soviet minefield, which immobilized 36 Panthers, stalling the division and rendering it vulnerable to Soviet antitank and artillery fire. As an officer in the division’s artillery observed:

Everything is shrouded in dust and smoke. The enemy observation posts certainly can’t see anything. Our barrageis now over…. It has wandered from the forward trenches farther to the rear. Are the infantry there? We can see some movement, but nothing specific…. General depression! My high spirits are gone.

The mines needed to be removed and scores of smashed tank tracks repaired before the advance could continue, a task that took several hours. The division’s offensive prospects, meanwhile, resided in the progress made on its right where a Tiger-led attack plunged forward, supported by waves of dive-bombing Stukas. This tenacity was ultimately rewarded with a hole in the Soviet line that led to the settlement of Cherkasskoe, 65 miles south of Kursk.

Mykhailo Petrik was one of Cherkasskoe’s defenders, fighting for his life with a machine gun that ripped through huge quantities of ammunition. As he recalled:

We had the enemy pinned down, but there was little cover and they tried to attack. Every time they moved, we shot them. A small pile of casualties grew. But then we saw that they had a mortar and before I could open fire, we had been hit. That mortar round knocked me unconscious and, in so doing, saved my life. When I came to that evening my partner was dead and I was covered in blood from a bad head wound. I was a mess. Deaf, confused and unable to stand. Despite this I can still recall the mixture of damp earth, cordite and blood which filled my nostrils as I assessed my situation. Clearly the Germans had passed by thinking us both dead…. That evening, having gathered myself, I headed north through the German lines and into the arms of comrades where I was patched up, given a rifle and sent to a trench. I did not last long. It was only hours later that I collapsed again. A shard of metal had, unknown to me, entered my neck from the mortar. My battle was over.

Cherkasskoe fell that afternoon. But despite Fourth Panzer Army’s success in puncturing the Soviet defenses on the first day of Citadel—a feat Walter Model’s Ninth Army mirrored in the north—the penetrations failed to live up to German expectations. Operation Citadel almost immediately fell behind the planners’ exacting timetable, and left senior commanders contemplating whether they possessed the power to achieve a breakthrough.

Over the next four days, as blitzkrieg degenerated into a protracted, grinding battle, it became increasingly clear that there was little chance German units could reach Kursk within the required timeframe. Ninth Army found it particularly difficult to gain any momentum as it desperately tried to make an impression against the Soviet line atop Olkhovatka ridge, the salient’s dominating physical feature. The ridge overlooked the low ground across which Ninth Army was to advance; its slopes became a killing zone.

At the village of Ponyri Station just to the east, the Germans became bogged down in a clash that became known to its

participants as a “mini-Stalingrad.” Soviet reporter Vasily Grossman, interviewing men who had fought in the village, heard disturbing stories of bloody hand-to-hand fighting and of 45mm cannons tussling with Tigers: “Shells hit them,” he wrote, “but bounced off like peas. There have been cases where artillerists went insane after seeing this.”

Ponyri was just one of many devastatingly intense battles fought along the high ground, and the combined impact of these slogging matches forced Model to change his plan and commit his armored formations to break the Soviet positions. But although the panzers added extra weight to Ninth Army’s attack, the Soviets were able to absorb whatever the Germans could throw at them. Indeed, by July 9, Model had squandered so many resources in his unsuccessful attempt to crack the defenses on the Olkhovatka ridge that he gave up on the attempt and subsequently limited himself to efforts that merely eroded the Soviet defenses.

By this point, Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army had managed to create a 15-mile-wide, 22-mile-deep wedge into the Red Army positions. But, critically, Nikolai Vatutin’s Voronezh Front had not collapsed. The chief of staff of XLVIII Panzer Corps, Friedrich von Mellenthin, was so impressed he later wrote, “The Russian High Command conducted the Battle of Kursk with great skill, yielding ground adroitly and taking the sting out of our offensive with an intricate system of minefields and antitank defenses.” Even if Hoth’s offensive lacked “sting,” however, it was so dogged and tactically astute that it weakened Vatutin’s defenses over the first week of the offensive enough that XLVIII and II SS Panzer Corps were on the cusp of breaking through the Red Army lines and into open country.

It was crucial for the Soviets that formations from Ivan Konev’s Steppe Front, which had been ordered forward to counterattack Fourth Panzer Army, reach the battlefield quickly. Eight hundred thousand men and 185 armored fighting vehicles of the Soviet Fifth Army streamed toward the front line south of Oboyan, 50 miles south of Kursk, while the 593 tanks, 37 self-propelled guns, and thousands of guns of the 5th Guards Tank Army pushed on to Prokhorovka, 22 miles to Oboyan’s southeast.

The riposte—planned to coincide with an attack across Model’s rear area just to the north of the salient on July 12—was designed to break Operation Citadel and force the Germans into a withdrawal. Hoth, however, had anticipated the arrival of the Soviet armor in the vicinity of Prokhorovka from the outset. He deftly ordered the remaining 294 tanks and assault guns of II SS Panzer Corps re-orientated away from their northern objectives to confront and destroy 5th Guards Tank Army. The stage was set for a monumental clash.

As Soviet formations, including those from Fifth Army, put pressure on XLVIII Panzer Corps, the largest armored clash of World War II—involving the 294 armored fighting vehicles of II SS Panzer Corps and 616 Soviet tanks and self-propelled guns—ignited west of Prokhorovka. Here Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Panzer Grenadier Division lunged forward and ran directly into what the commander of 5th Guards Tank Army, Lieutenant General Pavel Rotmistrov, described as “a cyclone of fire unleashed by our artillery and rocket launchers that swept the entire front of the German defenses.”

The preliminary bombardment smothered the battlefield in a blanket of dust and smoke. As soon as Rotmistrov’s guns fell silent he gave the code words, “Stal! Stal! Stal!” (Steel! Steel! Steel!), that released the tanks. Within minutes another great cloud of dust billowed skyward as Soviet T-34s and T-70s picked up speed.

At the sight of the dust cloud, the Germans immediately sent a warning to frontline units to prepare for the imminent arrival of a large enemy formation. Each panzer commander followed a well-practiced routine: he stopped his tank, identified a target, the gunner lined up the victim in his sights and then, when ordered, opened fire. The whole clinical process took just a few seconds, and was as efficient as it was effective. As Panzer IV company commander Rudolf von Ribbentrop, the son of German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, recalled:

What I saw left me speechless. From beyond the shallow rise about 150-200 meters in front of me appeared fifteen, then thirty, then forty tanks. Finally there were too many to count. The T-34s were rolling forward toward us at high speed, carrying mounted infantry [standing on the engine compartment and clinging onto handles welded onto the hull]…. Soon the first round was on its way and, with its impact, the T-34 began to burn.

Vasili Bryukhov, a T-34 commander, worked hard to keep his tank moving, but found it increasingly difficult as the ground before him became congested with entangled tanks and blazing hulks:

The distance between the tanks was below 100 meters—it was impossible to maneuver a tank, one could just jerk it back and forth a bit. It wasn’t a battle, it was a slaughterhouse of tanks. We crawled back and forth and fired. Everything was burning. An indescribable stench hung in the air over the battlefield. Everything was enveloped in smoke, dust and fire, so it looked as if it was twilight…. Tanks were burning, trucks were burning.

The battlefield became a chaotic swirl of action, which provided the tank crews with little respite as they fought in the most difficult of circumstances. Soviet T-34 driver Anatoly Volkov recalls:

“The noise, heat, smoke and dust of battle were extremely trying. Despite wearing protectors, my ears were extremely painful from the constant firing of the gun…. The atmosphere was choking. I was gasping for breath with perspiration running in streams down my face. It was a physically and mentally difficult business being in a tank battle. We expected to be killed at any second and so were surprised after a couple of hours of battle that we were still fighting—still breathing!”

Commanders found it difficult to tell friend from foe, as dust and heavy black smoke combined with darting armor to produce a deadly confusion. Panzer units excelled in the difficult circumstances, however, their crews working in harmony with their machines to out-think and outfight their more numerous opponents. Clear thinking, experience, radios, and tactics allowed the Germans to destroy more enemy armor than they themselves lost. The result was a German tactical victory at Prokhorovka—a remarkable achievement considering their numerical inferiority.

Yet it wasn’t enough to change the course of the operation. By this time it was clear that the Soviets’ tenacious defense and superior resources had run Operation Citadel into the ground.

Although Manstein attempted to salvage something from the operation’s sorry wreckage over the next few days, the efforts were merely a prelude to withdrawal. With pressure mounting in the Mediterranean—the Allies had invaded Sicily on July 10—and threats developing to the north and south of the Kursk salient as the Soviets built up their forces for a general offensive, Hitler called Citadel to a halt on July 23. Within a few weeks his troops were engaged in a headlong retreat along the entire southern front.

“And so the last German offensive in the east ended in fiasco,” Manstein later lamented, “even though the enemy opposite the two attacking armies of Army Group South had suffered four times their losses in prisoners, dead and wounded.”

He was right: the Soviets suffered more losses during Operation Citadel than the Germans. While Rokossovky and Vatutin lost 177,847 men, 1,600 armored fighting vehicles, and 460 aircraft, Model and Manstein suffered 56,827 casualties, and lost 252 tanks and 159 aircraft. But the losses on the Kursk battlefield were not as strategically critical to Moscow as they were to Berlin. Citadel backfired on Hitler in spectacular fashion, placing the Wehrmacht in a position whereby it could neither repel the Soviet counterattacks during late summer, nor the general offensive that followed during the autumn.

As a consequence, the failure of Operation Citadel was not only a pivotal moment in the campaign in the East, but in the Second World War. “As a result of the Kursk battle, the Soviet Armed Forces had dealt the enemy a buffeting from which Nazi Germany was never to recover,” the Soviet chief of the general staff, Aleksandr Vasilevsky, later wrote. “The big defeat at the Kursk Bulge was the beginning of a fatal crisis for the German Army.” Kursk exacerbated the Wehrmacht’s chronic shortages of men and materials, and left it ever more vulnerable to the unrelenting pressure exerted by its enemy. Indeed, as infantryman Raimund Rüffer put it many years later, the battle of Kursk was “a hellish nightmare that changed my life, the course of the fighting on the Eastern Front, and the entire war.”

Lloyd Clark lectures in War Studies at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst UK, is Professor of Modern War Studies at the University of Buckingham, and is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He is the author of numerous books, including Anzio: The Friction of War and Arnhem: The Greatest Airborne Battle in History, has contributed to numerous others and lectures on military history all over the world. Clark’s The Battle of the Tanks — Kursk 1943 will be published by Atlantic Monthly Press in 2011.

This feature originally appeared in the February 2011 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe today!