In 1918 the Czecho-Slovak Legion found itself fighting the Red Army in Siberia for control of the world’s deepest lake.

ONE OF THE MOST SPECTACULAR YET LITTLE-KNOWN STORIES of World War I and the Russian Revolution is the epic journey of the Czecho-Slovak Legion, whose exploits burst out of Siberia and onto the world stage almost 100 years ago. Subsequently lost in the multiple histories of a tumultuous time, the episode began as the final horrors of the war melted into chaos. In Russia, the revolution gave way to the birth of the Soviet Union, and the United States and its allies bungled a half-hearted attempt to overthrow its new Communist regime. In Europe, a fragile peace was declared, the fate of four empires hung in the balance, and the map of a continent was redrawn.

The legion emerged from an undistinguished array of shopkeepers, dentists, farmers, professors, factory hands, and bank clerks who were plucked from the obscurity of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the heart of Europe and plunged into World War I. After fighting on the Eastern Front—“the unknown war,” Winston Churchill called it—more than two million of these Austro-Hungarian soldiers were taken prisoner by tsarist armies and scattered across Russia and Siberia in some 300 prisoner-of-war camps. When tsarist Russia collapsed amid revolution, Tomas G. Masaryk, an elderly professor and fugitive from Prague, traveled to Russia with a vision involving outright sedition, a global trek, and great personal risk: to recruit thousands of Czechs and Slovaks for an ad hoc unit of the French army, their former enemy.

Masaryk’s plan was breathtakingly audacious: The men would cross Siberia to Vladivostok, the largest Russian port on the Pacific Ocean, where they would board ships, circle the globe, land in France, and fight on the Western Front—all to gain Allied support for the independence of the Czechs and Slovaks from Austria-Hungary. But defecting to the Allies meant committing treason. They would have no country they could call home, no recognized or experienced military leaders, no evident means of support, few supplies, uncertain legal status, questionable loyalties, and too few weapons. Many were still nursing combat wounds or illnesses. Remarkably, given the risks associated with such an audacious plan, the promise of renewed harsh combat, and Masaryk’s blue-sky ambitions, 50,000 to 65,000 of the men said yes. With the explicit approval of Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin, the men of the Czecho-Slovak Legion commenced a perilous journey across Siberia—where they had an unexpected encounter with history.

IT BEGAN ON MAY 14, 1918, WITH AN ALTERCATION between two men at the Trans-Siberian Railway station at Chelyabinsk, more than 1,000 miles east of Moscow. A still-loyal Austro-Hungarian soldier, angered by the legionnaires’ betrayal of their common homeland, hurled a chunk of metal at one of the defecting Czechs, killing him. The soldier was quickly apprehended and killed in retaliation. Subject to repeated arrests by the Communists in charge of Chelyabinsk, the legionnaires took matters into their own hands and liberated their comrades from the local jail. Having done so, they prepared to resume their journey. In response to this direct challenge, Leon Trotsky, the leader of the Red Army, telegraphed dire threats that his soldiers would shoot any armed legionnaires on sight and imprison the rest.

Already feeling imperiled amid the violence and rising tensions of an emerging Russian Civil War, and acting entirely in self-defense, 50,000 legionnaires revolted en masse. Strung out along 5,000 miles of the Trans-Siberian, the legionnaires were isolated in three major formations. From west to east, there were about 8,000 legionnaires marooned on the European side of the Ural Mountains near Penza; 8,800 in the vicinity of Chelyabinsk; about 18,000 east of Omsk; and 15,000 in and around Vladivostok. Yet between Irkutsk and Vladivostok, tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers, likewise trapped, lay in wait and prepared to fight.

The Czechs’ first priority was to link all of the legionnaires in a single chain—especially those around Penza, who were farthest from Vladivostok and the most vulnerable. From Chelyabinsk, Novosibirsk, and Penza, trains headed east and west under full steam to rescue their “brothers” and defeat the Red Army forces all along the Trans-Siberian Railway. Eager to surprise and quickly defeat the enemy, the legionnaires sometimes encountered forces that were far larger and better armed. Initially, without sufficient small arms, the legionnaires rushed Red Army units, throwing hand grenades and, in at least one battle, hurling rocks. They captured machine guns, rifles, artillery, and even entire trains and quickly deployed them against the enemy.

Day by day, week by week, one Siberian city after another fell to the Czecho-Slovaks: Novosibirsk on May 26, Chelyabinsk on May 27, Penza and Syzran on May 29, Tomsk on June 4, Omsk on June 7, Samara on June 8, Krasnoyarsk on June 20, Nizhneudinsk on June 24, Vladivostok on June 29, Ufa on July 4, Ussuriysk on July 5, and Irkutsk on July 11.

While about 15,000 of the legionnaires had reached Vladivostok by April, there were large Red Army units between that port city and Irkutsk, a major city just west of Lake Baikal, especially in the vicinity of Chita, and Khabarovsk. When the rebels finally entered Irkutsk on July 11 they were greeted with pealing church bells and celebrating Russians.

Having taken control of the Bolshevik strongholds of Irkutsk and Vladivostok, as many as 50,000 legionnaires nonetheless remained stretched out behind Irkutsk, cut off from their comrades in Vladivostok. Good intelligence quickly taught them that they faced a dangerous gantlet and a harrowing challenge: the 39 tunnels that sheltered the Trans-Siberian through the sheer cliffs along the southern shores of Lake Baikal, whose surface is larger than Belgium and whose depths hold a fifth of the world’s fresh water.

A 25-million-year-old scar on Russia’s backside, Baikal’s 400-mile, crescent-shaped gash in the tectonic plates holds a lake so large that locals call it a sea. Baikal drains the Russian heartland, swallowing the 336 rivers and streams that run to it; only the Angara River sends Baikal’s waters roaring west into the interior. Raw and unspoiled, the lake’s placid surface hides enormous depths. While transparent as a fishbowl in summer, in winter it can freeze to a depth of six feet. Razor-sharp rock lines the sheer cliffs that wall in the southern rim of the lake, sweeping toward the sky and plummeting deeply into the seemingly bottomless lake.

The opening of the Chinese Eastern Railway through Manchuria in 1903 completed the original Trans-Siberian Railway, but it avoided the mountainous 162 miles around the southern tip of the lake. When the builders of the railway finally tackled these mountain cliffs, which are bisected by the streams and river gorges feeding the lake, they had to dynamite cuttings into the sides of the rock walls; build more than 200 bridges and trestles to span river gorges, inlets, and tributaries; shore up miles of embankments; and bore through rock to create the 39 tunnels, the longest of them spanning a half mile. When this final link was opened in 1904—more than 13 years after ground was broken for the Trans-Siberian—the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans were finally linked by the Trans-Siberian, through adjacent seas.

SPOOKED BY THE CZECHO-SLOVAK LEGION’S RAPID ADVANCE in their direction, Soviet armed forces abandoned Irkutsk. The legionnaires soon learned that the retreating Bolsheviks had taken with them an entire train loaded with explosives, planning to blow up one or more of the tunnels, thereby trapping all the legionnaires west of Lake Baikal. Still, the boldness and energy of the legion’s commander at the front in Irkutsk, Captain Radola Gajda, gave his men confidence. “Gajda was a leader whose belief it was to strike at once, to strike often, and with determination,” recalled Sergeant Gustav Becvar. “In those days, he seemed never to hesitate in his course of action.” Gajda realized that he and his men had to reach and clear the tunnels as soon as possible to prevent their destruction.

Yet events in Irkutsk exposed the political weakness of the Czecho-Slovak Legion’s position in Russia, even as the world marveled at its military prowess. “As if by magic, law and order were established,” Ernest Harris, the American consul general in Irkutsk said, “and the streets became crowded with every class of society exceedingly happy at having been rescued from Bolshevik rule.”

The residents of Irkutsk warmly welcomed the legionnaires. At a celebratory dinner, Becvar recalled, “I began by thanking the people for the wonderful reception they had given us, saying how much we appreciated their goodwill. These remarks went down well, but when I proceeded to warn them that we had no intention of interfering in any way in the internal affairs of their country, that any fighting we had done had been undertaken solely to secure our passage to Vladivostok, and that therefore we could not be relied upon to stay in the neighborhood of Irkutsk, they were less pleased. After this announcement, much of the joy occasioned by our arrival evaporated.” The Allies would also need to be taught that the Czecho-Slovaks did not actually want to fight Russians.

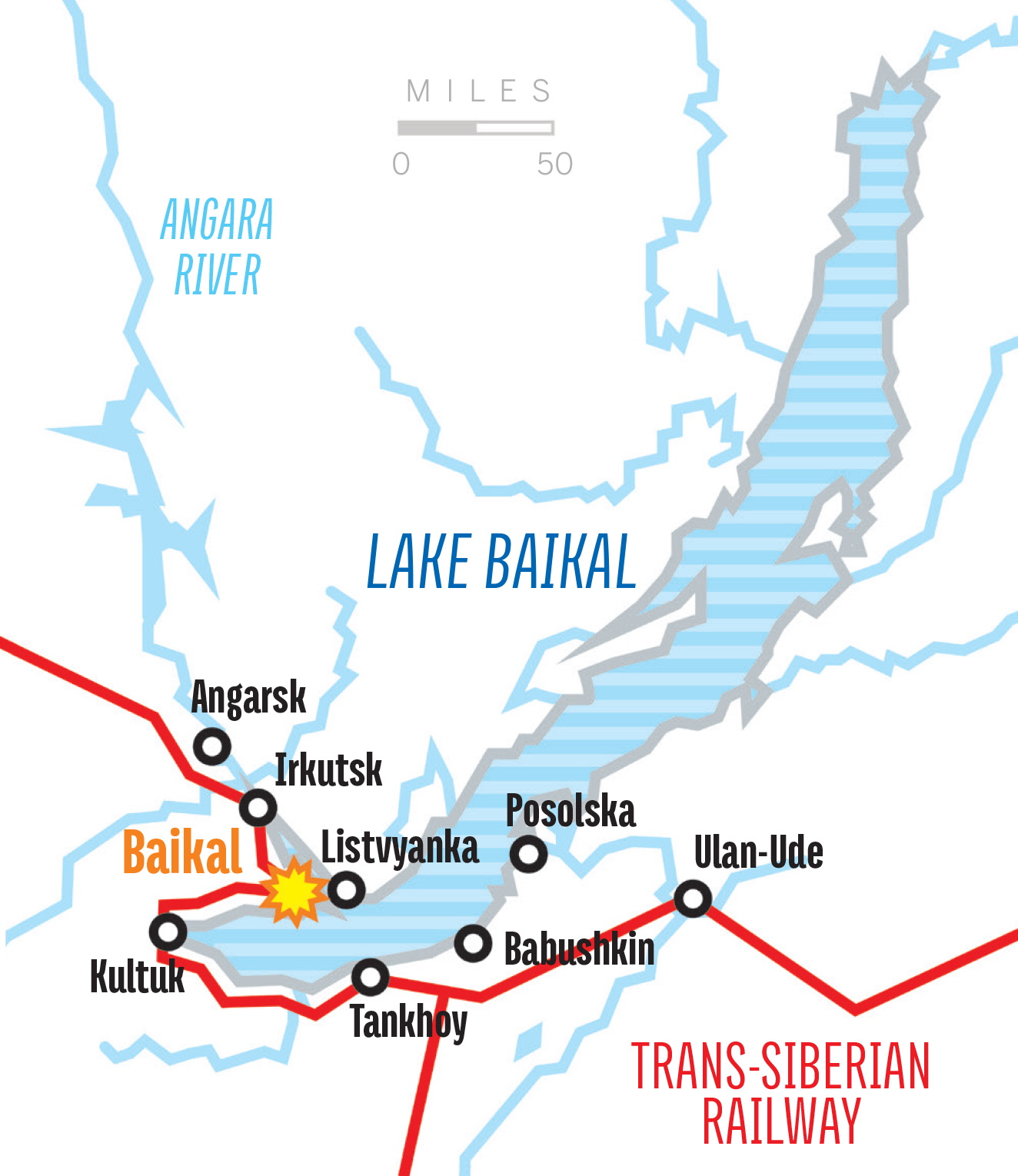

At Irkutsk, the Trans-Siberian was built on the opposite side of the Angara River from the main center of the city, and the tracks originally ran east along the Angara for about 40 miles until they reached Lake Baikal at the village of Port Baikal. The ice-breaking ferries Baikal and Angara shuttled passengers, trains, and freight from Port Baikal across the lake to Babushkin until 1904, when the “missing link” was completed, with two tracks running 162 miles around the southern tip of the lake from Port Baikal to Babushkin on the lake’s eastern shore. It was at Port Baikal, the legionnaires learned, that the Bolsheviks had parked their explosives-laden train. The station and its tracks sat between the steep cliffs above Port Baikal and the mouth of the Angara River at the lake.

On July 15, 1918, Gajda dispatched three parties in the direction of the enemy. One unit of 500 men hiked cross-country and quietly approached another lakeside village, Kultuk, south of Port Baikal. A second party followed the Trans-Siberian down the Angara valley toward Baikal but kept to the hills above the valley to avoid detection; an armored train the legionnaires had captured from the Red Army followed slowly behind and to the left of these men. On the opposite side of the Angara valley, a third unit followed the old Moscow post road from Irkutsk to the lakeside village of Listvyanka, opposite Port Baikal at the mouth of the Angara. This third unit turned left off the road as it approached Listvyanka and climbed into the hills above the village. After a few hours, a ridge appeared and the men crawled to its edge and looked below them in wonder at the enormous sparkling lake spread out beneath them. Off to their right in the distance sat Baikal station, where the lake emptied into the Angara. “We stared silently at the indescribable loveliness of the view,” Becvar recalled. “Men drew their breath quickly, but few broke the silence.”

Suddenly, from the direction of the Baikal station, came the sound of a huge explosion. A column of thick, black smoke rose into the air. Assuming this signaled their attack, Becvar and his men ran toward Listvyanka, firing at enemy troops who scrambled aboard two steamers that vanished across the lake. As they crept forward cautiously, the first legionnaires to reach Port Baikal saw buildings leveled, tracks twisted, coaches shattered, rockslides, and body parts everywhere. Their comrades who had earlier reached the cliffs above the station confessed that when they fired on the enemy train, some of their rounds probably hit dynamite.

Gajda appeared and ordered most of the men to pursue the Bolsheviks through the tunnels on foot. A small detachment remained behind to repair the tracks and allow the legion’s armored train through. Early the next morning, troop trains began moving through the tunnels toward Kultuk; other troops were dispatched into the hills above the tunnels. After five days of fighting, the combined three units of legionnaires took Kultuk. The soldiers then advanced toward Slyudyanka, a town on the southern tip of Lake Baikal, beyond which lay the last of the 39 tunnels. Then came another booming explosion that echoed through the tunnels and across the lake to their left. The men ran ahead until the tracks in front of them disappeared under a pile of stone and earth.

It took the legionnaires three weeks, working day and night, to clear the massive stones and earth from the tracks. Yet they used the time well. Planning to hit the Bolsheviks simultaneously from three sides, they boarded their one armored train and several passenger trains and rounded the southern cone of Lake Baikal, heading toward Tankhoy, a town on the eastern shore.

“The Bolsheviks were entrenched strongly in front of this station, and not even our newly arrived armored train could shell them out of their fortified nests,” Becvar later wrote. Scouts spotted about 60 Red Army troop trains crowding the line between Tankhoy and the station at Babushkin, which was farther north along the shore. Gajda briefed the men: legionnaires left behind at Listvyanka on the opposite side of the lake had acquired simple barges that they fortified with timber, as well as steamboats that could tow the barges. The boats would start across the lake that night, landing at yet another lakeside village, Posolska, north of Babushkin, behind the Red Army forces. At the same time, another battalion would march east into the taiga and, in a wide flanking move, approach the enemy from the east. The remainder of the troops would advance along the tracks behind the legion’s armored train.

The Red Army soldiers fought hard. By about noon, however, they began bolting from their lines, and soon the whole front was in retreat, undoubtedly having gotten wind of the legionnaires approaching from their rear. “Then the retreat turned into a positive rout,” Becvar later wrote. “The Bolsheviks were given no time or opportunity to use their trains. They were driven in a panic-stricken mass along the line towards Posolska.” What awaited them was a massacre. “Rifle and machine-gun fire raked the driven mob until they scattered into the hills.” Red Army casualties numbered in the hundreds; the legion gained countless trains and a larger arsenal. The legionnaires also set ablaze the Baikal, ending its career at the dock at Babushkin.

THE RED ARMY FORCES DID NOT SOON RECOVER from these defeats. With Lake Baikal’s 39 tunnels behind them, dozens of the legion’s heavily armed trains started west again. On August 24 they reached Ulan-Ude, a city about 60 miles east of the lake. The men who had been trapped west of Lake Baikal finally saw their “brothers” from Vladivostok when, on September 1, the legionnaires celebrated their final juncture in Olovyannaya, meeting legionnaires from Vladivostok, who had fought their way along the Chinese Eastern Railway to this small town south of Chita.

That same day, in an ironic coincidence, U.S. Army major general William S. Graves came ashore at Vladivostok with orders to rescue the legionnaires—but to do nothing more than facilitate their retreat to Vladivostok and evacuation. Yet the legionnaires had already facilitated their own free movement toward Vladivostok, leaving Graves and his troops with little to do. On top of that, the Allies by now had abandoned their faint hopes of providing ships to take the legionnaires from Vladivostok, and the French and British began lobbying for the legionnaires to remain in Russia to support the anti-Bolshevik forces under attack by the Red Army, and even to advance on Moscow. Thus began the confused and ill-fated Allied

intervention in the Russian Civil War. Afterward Graves nicely summed up his experience this way: “I was in command of the United States troops sent to Siberia, and, I must admit, I do not know what the United States was trying to accomplish by military intervention.”

Still, in little more than three months, the legion had seized the entire Trans-Siberian Railway and, with it, all of Siberia from the Ural Mountains to the Sea of Japan—about the distance from Honolulu to New York. Siberia’s five million square miles account for a tenth of the world’s land surface. While their feat astonished many, those who had come to know the men were less surprised. The British writer, W. Somerset Maugham, who worked with the Czechs and Slovaks inside Russia as a British spy, warned, “They are organized like a department store, disciplined like a Prussian regiment.”

Roughly 15,000 more Czech and Slovak POWs joined the legion after the revolt began, leading Trotsky and Lenin to see it as a threat to Soviet rule. Speaking to an extraordinary joint session of Soviet leaders on July 28, Lenin said that “crushing the Czecho-Slovaks and their counterrevolutionary partisans” was “the most urgent task of the Russian Revolution.” Speaking to the same assembly the next day, Trotsky conceded: “What is now happening on the Volga, in the shape of the Czecho-Slovak mutiny, puts Soviet Russia in danger and therefore also endangers the international revolution. At first sight it seems incomprehensible that some Czecho-Slovak Corps, which has found itself here in Russia through the tortuous ways of the world war, should at the given moment prove to be almost the chief factor in deciding the questions of the Russian revolution. Nevertheless, that is the case.”

THE CZECHO-SLOVAK LEGIONNAIRES BRIEFLY HELD THE POWER to depose the Soviet regime, an outcome that would have dramatically changed the course of the 20th century. Their revolt also had many unintended consequences. Their advance against Red Army forces in the city where the Romanov family was held in July 1918 directly precipitated Lenin’s order to murder Tsar Nicholas II and his family. The legion hastened the development of the Soviet gulag with the founding of the first concentration camps, and it also spurred the early buildup and configuration of the Red Army. Their rebellion was the main reason that President Woodrow Wilson sent U.S. troops to Russia, deployed explicitly to aid the Czechs and Slovaks.

Yet the legion’s willingness to fight for the Allies helped to undermine the Habsburg dynasty and enabled Masaryk and his associates to secure Allied recognition for the republic of Czechoslovakia. Winston Churchill, who served as British war minister during the revolt, concluded, “The pages of history recall scarcely any parallel episode at once so romantic in character and so extensive in scale.” In rare agreement with Churchill, British prime minister David Lloyd George said, “The story of the adventures and triumphs of this small army is indeed one of the greatest epics of history.” Former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, long out of office and grieving the death of his son in the war, was inspired by reports of the legion’s achievements in Russia. He donated $1,000 of the cash award he had received from his 1906 Nobel Peace Prize to the legionnaires, “the extraordinary nature of whose great and heroic feat,” he said, “is literally unparalleled, so far as I know, in ancient or modern warfare.” His mortal enemy, Woodrow Wilson, agreed, later welcoming legionnaires to the White House.

The “pages of history,” however, have not done much justice to these men. This tale of the founding of Czechoslovakia was suppressed after 1938, when Germany’s Nazi regime occupied the small nation, where anti-German sentiment had long walked hand in hand with Czech nationalism, and again after 1948, when Czechoslovakia became a Soviet satellite. Prague’s Russian occupiers buried the memory of the founders of Czechoslovakia, who had fought and defeated, albeit briefly, the Red Army and threatened the very survival of the Russian Revolution. It was not until after the communist regimes of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe collapsed that this story could be told using original source material.

Fighting against the Red Army in the Russian Civil War had the unfortunate effect of characterizing the Czecho-Slovak Legion, at least in some quarters, as a reactionary, pro-tsarist army. Yet the men risked their lives to oppose a monarchy in Vienna, not to support one in Russia. All available evidence confirms that most of the men, as well as their leaders, were socialists, and about 10,000 Czech and Slovak POWs volunteered for the Red Army. Finally, they despised and openly opposed the leading White commander, Admiral Aleksandr V. Kolchak, even turning him over to a neutral revolutionary tribunal in Irkutsk in January 1920. The origins and aims of these Czech and Slovak legionnaires, the youngest sons of Europe’s last medieval empire, would more appropriately characterize them as the last revolutionaries of the ancien régime. Only novel political concepts and categories then emerging from Soviet Russia could classify these revolutionaries as the first counterrevolutionaries of a new era, when the exuberant mood of the last innocent age of nationalism collided with the dawn of international socialism and Soviet communism. MHQ

KEVIN J. McNAMARA is an associate scholar of the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia, and a former contributing editor of its quarterly journal, Orbis. He is the author of Dreams of a Great Small Nation: The Mutinous Army that Threatened a Revolution, Destroyed an Empire, Founded a Republic, and Remade the Map of Europe (Public Affairs, 2016), from which this article is adapted. Copyright © 2017 by Kevin J. McNamara.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2017 issue (Vol. 29, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Battle for Baikal.

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!