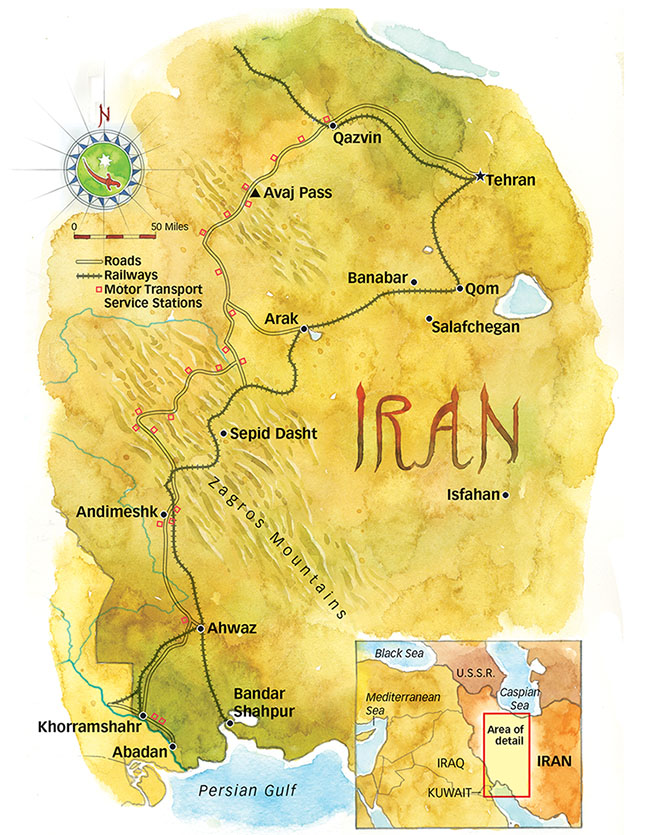

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]N A CHILLY AFTERNOON in late 1943, a U.S. Army train was chugging north between Arak and Qom, Iran. The trip had departed Khorramshahr, on the Persian Gulf. At Tehran, Red Army railroaders would take over, shepherding train and cargo into the U.S.S.R. to supply the fight against the Germans. For the delivery crew—an engineman, a fireman, and a conductor, all GIs, plus an Iranian brakeman—operations like this usually were milk runs.

But not today.

Today’s 1,000-ton load was 10 tankers of volatile aviation fuel, plus 11 boxcars packed with ammunition and high explosive. And the big steam locomotive’s throttle was jammed wide open.

The train had just summited the towering Zagros Mountains at a point nearly 200 miles north of the Gulf when the throttle valve sheared. The locomotive’s power plant was revving at peak output as the train started a 2,500-foot descent that would last 42 miles—if it stayed on the tracks. Engineman Virgil E. Oakes hit the air brakes, but only four cars had them; of the rest, few had working brakes. Oakes tried reversing the drivers. No go. The train obeyed the laws of physics, quickly accelerating to 65 miles an hour. Like the rest of the crew, the fireman—Corporal Harry Slick, 23, a Pennsylvanian with a passing resemblance to actor Robert Taylor—was clinging for dear life.

When the train ripped past Sergeant Seth Hood at his desk railside, the astonished dispatcher grabbed his phone. A dozen miles further along, four trains were on a collision course with the runaway. “Clear the track!” Hood bawled to stations up the line. The rails began to climb to Banabar; the crewmen hoped the incline would slow them to a stop. It did not. Past Banabar, the rails angled downhill again, and again the train gained speed, hitting 90 mph and rounding a bend into a wide valley. At Salafchegan, 11 miles ahead, three columns of smoke were rising; Slick and his companions assumed that meant a train on the main line and one on each adjoining set of rails, leaving them no passage.

Engineman Oakes ordered all hands to jump from the train. He went first—breaking his skull among other injuries that would hospitalize him for a year—

followed by conductor John P. Peterson, who landed in soft soil, bruised but intact. No record exists of what the brakeman did, but Harry Slick, too scared to leap, stayed huddled aboard, figuring he had a fatal appointment at Salafchegan.

Slick could not know that the dispatcher’s alert had come in time for crews in the valley to clear the main line, and from so far away Slick could not see that at Salafchegan there were not three but two trains, both on sidelines, one with two locomotives. The main line was clear and, to Slick’s shock, instead of crashing he blew through at full speed. Now he and his trainload of trouble were closing on a 90-degree curve. In the cab Slick hunkered, fingers crossed, as gravity tugged him sideways. By some quirk the wheels stayed on the steel. The train even lost speed. Slick grabbed the reverse lever and yanked. The drive wheels bit, and the train began to slow. The runaway stopped just outside Qom.

Harry Slick had stayed alive, averted disaster, and saved a critical cargo. Besides the U.S. Army’s Soldier’s Medal he received the Soviet Order of the Red Star. It was another day in the life of the Persian Gulf Command, the main Allied supply line to Russia. On this unheralded but essential conduit, men shipped arms and materiel in remote obscurity amid astonishingly extreme conditions.

They called themselves “the Forgotten Bastards of Iran.”

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]HEN HARRY SLICK enlisted, the day after Pearl Harbor, he was perfect infantry material: young, fit, and eager. But here he was, a corporal, thousands of miles from combat, firing not a rifle but steam locomotives—the job he had had with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the job his dad had had before him.

Slick was in Iran as part of a massive program providing the U.S.S.R. with Lend-Lease equipment, fuel, ammunition, food, and medical supplies. The effort required 30,000 GIs, including as many Harry Slicks as the military could recruit, along with mechanics, drivers, and Iranian civilians.

The Persian Gulf Command had its roots in Operation Barbarossa. Germany’s June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union had the Soviets and British worrying that Hitler would snatch Iran and its oilfields—no great challenge, given Reza Shah Pahlavi’s Nazi leanings. German control over the Mediterranean was denying the Allies land and sea routes to the Black Sea by which to supply the U.S.S.R.; ocean convoys to the arctic ports Archangelsk and Murmansk were delivering the goods. To keep the Reich out of Iran, Great Britain and the Soviet Union forced out Pahlavi, installing son Mohammed Reza Pahlavi as their puppet. The coup not only denied Germany access to Iran but opened a land and air corridor along which Lend-Lease arms and materiel could travel to the U.S.S.R.

The British began expanding existing Iranian highways and railroads, but ran short on resources. In September 1941 the empire asked the nominally neutral United States to throw in. The U.S. Military Iranian Mission, a cadre of army and civilian engineers, mobilized to modernize the Persian Gulf ports of Khorramshahr, Abadan, and Bandar Shahpur, expand Iran’s single-track rail system, and complete construction of a 700-mile highway to substitute for the rail line if the Axis bombed it.

GIs landed in force in December 1942; 9,000 engineers, technicians, truck drivers, and railroaders came in at Khorramshahr. Within weeks the 762nd Railway Diesel Shop Battalion—whose ranks included Private First Class Herbert Bernard “Rags” Ragsdale—followed. The Kentuckian was slight, had piercing brown eyes, and sported a dashing Ronald Colman moustache. Rags Ragsdale, 21, had acquired his railroad skills as a yard clerk on the Illinois Central, the same outfit his forebears had worked for.

As his troopship docked at Khorramshahr, Rags scanned the harbor, where a long pier could handle seven Liberty ships; in the Shatt-al-Arab waterway, freighters awaiting slots bobbed at anchor. Working alongside Iranian stevedores, three battalions of army dockwallopers were emptying Liberty ships. Crews swarmed to guide giant crates being winched out of holds and onto flatcars. Bucket brigades hand-to-handed sacks of grain and rice and cement into 6×6 truck beds. Operators at the controls of 80-ton cranes were swinging M4 Sherman tanks from ships’ holds to Iranian soil and the black hulks of partly assembled diesel locomotives onto spur lines. These engines and other rolling stock would become the Iran arm of the U.S. Army Military Railway Service. “Russia is certainly getting an enormous amount of equipment from the U.S.,” Rags wrote in his diary. “Every kind imaginable.”

Every kind of equipment imaginable was what the Soviet Union desperately needed. By early 1943 the Americans had fully taken over Lend-Lease activity in Iran. The mission had four elements: Transport the goods. Offload the transports. Assemble the gear. Get the gear to the U.S.S.R. To reach the Persian Gulf, Liberty ships, each carrying 10 to 15 trainloads of materiel, sailed from America’s east and west coasts. The 14,000-mile eastern passage rounded the Cape of Good Hope and steamed along East Africa; ships departing western ports sailed 18,000 miles past Australia and India. At peak, in the summer of 1944, stevedores at the three Iranian ports were discharging as much as 9,000 tons of cargo a day.

For railroaders, the army skimped on military training, leaving recruits like Ragsdale not the snappiest of soldiers. One hot day in 1943—a 120°F afternoon was not unusual—Rags hacked his government-issue khakis into shorts, triggering a tirade from his sergeant, a veteran of the regular army. “I told him what I thought of him, and the rest of this Army,” the railroad man wrote in his diary.

Heat was the chronic complaint among soldiers. Southern Iran’s deserts vied with Death Valley for the title of “hottest place on Earth,” and men stationed in the former understood why. May to October, temperatures averaged 107°. Ragsdale wrote that July 1, 1943, was “hotter than blue blazes,” with the mercury above 160°. That was no hyperbole. In August 1944, the 113th Army General Hospital at Ahwaz recorded a high of 168°. Yank, the army weekly, ran a gag:

A GI dies and goes to Hell.

“What was your last post?” asks the Devil.

“Andimeshk.”

“Ohh,” the Devil says. “In that case you better rush over to the supply room and draw your woolen underwear and winter coat.”

Early on the army set up “heatstroke centers” that began as tents and evolved into what New Yorker correspondent Joel Sayre, who profiled the command in a four-part series in 1945, described as “fancy caverns sunk in stone, as comfortable as the Pentagon Building.” Field treatment was primitive, consisting mainly of “sloshing men down with ice water and pouring cold drinks into them.” Men sponged tools and other metal objects before picking them up. Dog tags stayed in pockets. Most men were off during the blast-furnace afternoons, with work resuming in the evening.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ISTORICALLY, African American GIs did the army’s heavy lifting; 5,000 of them were assigned to Iran. Black soldiers drove trucks, maintained roads, ran bakeries and laundries, and worked the docks, where the army feared white GI stevedores would bristle at their presence. Tensions, never pronounced, resolved into an almost-friendly rivalry. Each month a flag went to the gang, black or white, that unloaded the most tonnage. More often than not, the African Americans took the banner.

The army tried to segregate housing and recreational facilities, even at remote outposts, but reality slackened those strictures. Outside the plateau city of Qazvin, in northern Iran, the 435th Engineer Dump Truck Company worked supply depots. Side by side with Soviet soldiers at “Camp Stalingrad,” the black GIs transferred materiel to the Red Army and, far from official scrutiny, “encountered less discrimination here than back home in the States,” said Supply Sergeant Clifford B. Cole. Men who at home would have had to climb to a balcony to watch a movie could “sit anywhere in the enlisted men’s section at the theatre,” Cole noted.

As soldiers often will when off-duty, black GIs changed into civilian clothes, sometimes going so far as to dress themselves in the flowing style favored by locals.

New Yorker reporter Sayre included in one of his reports an account of American military policemen seeing two white-robed men with elegant gold bands securing their headwear. Their skin was much darker than the average Iranian’s, arousing the MPs’ suspicion. The patrolmen stopped the pair for a conversation that took an unexpected turn when the military policemen noticed poking from beneath the hem of one man’s robe the toes of his GI shoes.

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]UCH CARGO FLOWING north for transport into the Soviet Union was vehicular: jeeps, command cars, weapons carriers, fire engines, wreckers, ambulances, trucks, locomotives, and aircraft. All these had to make their way to Russia under their own power. Ragsdale’s battalion had the job of assembling modified 1,000-horsepower ALCO RSD-1 diesel-electric locomotives and thousands of freight cars. The locomotives, made in Schenectady, New York, by the American Locomotive Company, had arrived before the railroaders and without the requisite tools, so the diesel shop boys forged their own implements and set to work. Within days of landing in Iran the 762nd was sending an RSD-1 out the shop door. “Pioneers in Diesel Railroading,” wrote Rags. “It makes us feel good.”

Another assembly line produced that common denominator of military transport, the open-bed truck. Vehicles came crated in chunks: chassis, engine, bed, cab, and wheels, each in its own box. From the clerk’s desk at the diesel shop in Ahwaz, 70 miles north of the ports, Ragsdale watched long trains pass stacked with crates marked “Cased Motor Truck.” At Khorramshahr and at Andimeshk, 175 miles north in the Zagros foothills, the army, aided by General Motors, had built two truck plants where thousands of Iranians were turning out more than 100 vehicles a day, mostly Studebaker US6s. Assembly crews needed only minutes to wrestle a jumble of components into an operable vehicle, whereupon Soviet inspectors checked each “Studer” from tarpaulin to tires, chalking initials on the doors of trucks that passed muster. Studebaker fleets set off daily for the Motherland with Red Army drivers at the steering wheels. The Soviets had hoped for 2,000 trucks a month; they got an average of 7,500.

Khorramshahr was also producing aircraft. “Russian planes flying over all day,” Rags wrote. “Very low.” The planes came from a plant at Abadan that Douglas Aircraft helped build. Its inventory was not the hottest, but the stock was reliable and plentiful: Bell P-39 Airacobras and Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters and Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers and B-25 Mitchell medium bombers.

Like Studers, planes came crated. The largest, 10 feet high and 38 feet long, held a P-40 or P-39 wing with landing gear. A slightly smaller crate held the fuselage, Allison V-12 engine bolted in place. Army Air Forces technicians did most of the assembly; American pilots handled test flights. Once paint crews laid on red stars, Soviet pilots flew the planes home—often straight into battle. They especially liked the P-39, which did well against Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs.

Millions of tons of materiel had to be shipped, whether by train or the army’s vast trucking operation, the Motor Transport Service (MTS), staffed by thousands of gear jammers like Private Robert C. Patterson of Washingtonville, Pennsylvania. The tall, affable driver, 21, had been hauling beer and fertilizer when he enlisted in November 1942—only to have his draft board balk, claiming truckers were needed at home. “After a heated discussion they finally agreed” to let him join up, he said. Churning dust that

choked man and machine, Patterson and fellow wheelmen rolled between the Gulf ports and Qazvin. This four-day, 636-mile trip, on a road laid over a camel track, traversed a salt desert and crossed the Zagros Mountains. The 175-mile desert leg to Andimeshk often involved blinding sandstorms. From there the highway followed a 2,500-year-old caravan route into the Zagros featuring switchbacks, hairpin turns, and bridges spanning chasms. The pinnacle was 7,700-foot Avaj Pass, in winter as cold as -25° and often blocked by snow. The descent, as perilous as the climb, led to Qazvin’s sprawling depot, where the Red Army took delivery.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]HE MAIN ENGINE of Persian Corridor aid was the Military Railway Service (MRS), which hauled four tons for every ton carried by truck. Dating to the Civil War, the service had worked in Europe in 1917-18, supplying American forces from dinky, narrow-gauge railways. Now the MRS had divisions on four continents. In Iran, tanks and other loads too heavy for trucks rode the rails. So did refined fuels and ordnance.

Iran’s prewar rail system was, according to The Christian Science Monitor, “1,200 miles of twisting track through desert waste lands and dizzying mountain peaks, with terminals that went from nowhere to nowhere” and practically zero hauling capacity. The U.S. Army built new tracks and updated infrastructure. In the desert the rails paralleled the military highway, but at Andimeshk the rail line took its own tortuous path through the Zagros, where the original builders had devised elegant solutions to challenging terrain that the military railroaders had to keep using.

In rocky canyons 85 miles north of Andimeshk, the line made two giant underground loops, one beneath the town of Sepid Dasht. In 165 miles, the rails passed through 135 tunnels that at first gave army railroaders fits because they were using coal-fired steam engines whose exhaust fouled the unventilated galleries. Cab temperatures could exceed 180°. Crews took to slowing to a crawl, jumping from the cab, and walking alongside the train in the cooler, fresher air at ground level. Diesels burned cleaner, making “running the ratholes” easier and healthier. From the Zagros summit, the line descended to Tehran, where Russian rail crews took over for the 300-mile stretch to the Caspian Sea.

Iran abounded with Soviets, but the Red Army discouraged fraternization, so GI Joe and Ivan rarely socialized, though men improvised insignia swaps and occasionally shared jolts of vodka. Bob Patterson recalled the Russians he met as “rude, mean, and arrogant.” But in his diary Rags Ragsdale movingly described how at Ahvaz he met a young soldier who had been wounded at Stalingrad: “Saw his mother and dad killed. Buried his mother himself.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]N AUTUMN 1944 the equation changed. The Allies took the Mediterranean, allowing aid for the U.S.S.R. to pass through the Black Sea. The Allied presence in Iran began to shrink. Truck convoys stopped rolling that November. In December the Abadan aircraft and Andimeshk truck plants closed, the latter shipped—in crates—to the U.S.S.R. The Iranians got their railroad back the next spring. On May 21, 1945, Ragsdale made his final wartime entry: “The first flight flew out tonight. Won’t be long now.”

In its 34 months, the Persian Gulf Command had assembled and delivered 184,000 vehicles and nearly 5,000 planes and hauled more than 3.4 million tons of supplies. That effort shortened the war on the Eastern Front 12 to 18 months, according to historian David Glantz. Iran’s part strongly affected that nation’s interactions with the United States. Until the war, the Middle East largely had been an Old World sphere of influence. Afterward, however, a growing appetite for oil increased American involvement in the region. In the Cold War, the proximity to the U.S.S.R. that had made Iran crucial during World War II led the United States into a fraught relationship that continues today. ✯

Originally published in the May/June 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.