When Wilbur Wright went to France in 1908 to demonstrate the Flyer to skeptical French officials, he followed his dazzling aerial displays near Le Mans by offering to give rides to women in the crowd. Among those who took him up on that offer was the beautiful young French actress Raymonde de Laroche. It would mark the beginning of her lifelong—though tragically brief—love affair with flying.

Born Elise Raymonde Deroche on August 22, 1886, she grew into a tall, shapely woman with long dark hair and expressive brown eyes. Success on the stage combined with her flamboyant personality and keen sense of style to establish her as one of France’s fashion icons by her early 20s. She changed her name to Raymonde de Laroche, believing it had a more dramatic ring.

Laroche claimed to be a lot of things, including a painter, sculptor, balloonist, bicyclist and racecar driver. She clearly liked living on the edge and enjoyed her notoriety. But none of her previous adventures compared to riding in Wright’s aircraft, which inspired her to ask French aviator (and some believe her lover) Charles Voisin to teach her to fly.

In 1909, 23-year-old Laroche joined Voisin at the Châlons airfield, where he and his brother, Gabriel, built and flew their own planes. The Voisin was a single-seater, so a pupil had to sit alone in the plane and take direction from a trainer who shouted orders from the ground. During Laroche’s first lesson, Voisin instructed her to drive the plane along the airfield. When she reached the other side, a mechanic turned the plane around and she taxied back to the starting point. She was not, under any circumstances, supposed to lift off.

Ignoring Voisin’s strictures, after her first taxi trip around the field Laroche opened up the throttle, raced down the airstrip and rose about 15 feet in the air. As one witness, British reporter Harry Harper, wrote, the plane “skimmed through the air for a few hundred yards, and then settled gently and came taxiing back.”

Laroche’s lessons continued over the next few months, and she became more confident in her flying skills, but her training was not without mishaps. On January 4, 1910, she survived a potentially deadly crash after her plane clipped some trees at one end of the field. Her injuries were relatively minor—a broken collarbone and a few bruises—and apparently didn’t keep her down for long, as she traveled to Egypt the following month with the Voisins to compete in the Heliopolis air meet. Despite heavy rains and winds, 12 aviators competed, among them Laroche. First place went to Henry Rougier, who flew 95 miles despite the bad weather. Laroche came in eighth.

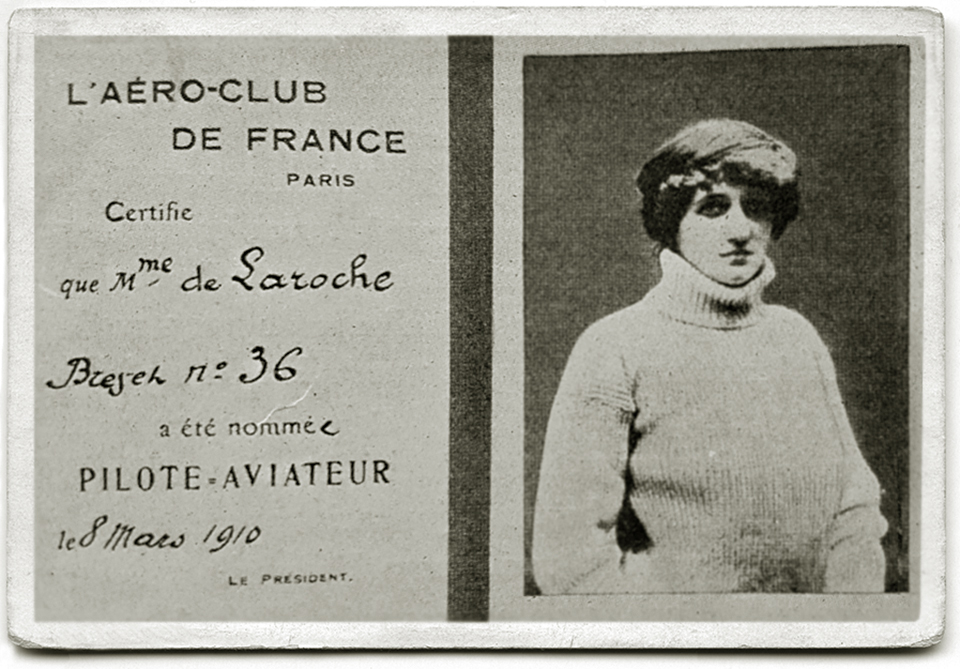

Her next mission was to face the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. On March 8, 1910, Laroche duly impressed the French officials and was granted pilot’s license No. 36—the first issued to a woman. By that time the press had nicknamed her la femme oiseau (the bird woman), but she had also given herself a royal title, baroness.

Laroche set out to travel the world, barnstorming as she went. In St. Petersburg, Russia, she demonstrated her flying skills over a small airfield where smoking chimneys not only reduced visibility but resulted in unstable air currents. After circling the field at more than 300 feet, she turned off her engine and glided down to a landing, leaving Tsar Nicholas II and other observers in awe.

Recommended for you

Over Budapest more chimneys wreaked havoc during a competition, but Laroche took first place because no one else attempted the 68-mile course. In Normandy she was caught in a storm and crash-landed into a fence surrounding the field, skillfully avoiding the assembled spectators. Once again she got off lucky, suffering only a concussion and another broken collarbone.

Later that summer at Rheims, Laroche was the only woman pitted against male competitors at the Seconde Grande Semaine. The baroness’ luck held until the sixth day of the competition, when she crashed again, breaking her arm and both legs. When she came to, Laroche claimed that another plane had come too close, forcing her down from 200 feet. She was furious to discover that the careless pilot who caused her accident had not been disciplined.

This time her crash stirred up controversy. Women had no place in the world of aviation, or so went the conventional wisdom of the day. Women could not handle emergencies and were not as capable as men. Only a man could handle a flying machine—besides, flying was totally unladylike.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Laroche would have none of it. Sporting her trademark white sweater, she was back in the pilot’s seat two years later. This time she had her eye on a prize of 2,000 francs offered by Pierre Lafitte, owner of Fémina magazine and sponsor of the Coup de Fémina flying competition for women. The prize would go to the woman who flew the longest distance solo by December 31, 1912.

As it happened, another kind of crash kept Laroche from competing that year. She and Charles Voisin were driving near Lyons on September 25 when they collided with another car. Voisin died at the scene, while Laroche suffered serious injuries. Despite her grief at Voisin’s death, she was more determined than ever to return to the air.

By 1913, Laroche had tried flying a Sommer, similar to the Voisin, then switched to another biplane—a Farman, which she felt was easier to handle. Following another auto accident, Laroche took to the skies later that year hoping for a second chance at winning the Coup de Fémina. On November 25, she flew a total of 200 miles in four hours before a gas line problem forced her down. She claimed the prize at year’s end.

The onset of World War I brought civilian flying to a halt in 1914. Women like the baroness who offered their flying skills to the war effort were turned down. Laroche instead drove an automobile for the French. But as soon as the war ended in 1918, she set her sights on becoming the first female test pilot. She broke the women’s altitude record on June 7, 1919, climbing to almost 13,000 feet in a Caudron G.3. Three days later, however, American Ruth Law bested that record by flying to 14,700 feet. Not to be outdone, Laroche reached an astonishing 15,748 feet on June 12.

On July 18, 1919, she visited Le Crotoy airfield, where a test pilot offered her a ride in an experimental Caudron. As they started to land, the plane went into a spinning dive, plummeting to earth. The 33- year-old baroness was pronounced dead at the scene, and the pilot succumbed on his way to the hospital.

In an era when female fliers were rare, Raymonde de Laroche welcomed the challenge of earning her place in the cockpit. A statue honoring her stands at Paris’ Le Bourget Airport.

Originally published in the July 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.