Coleman was born on January 26, 1893, in Atlanta, Texas. She was just learning to walk when the family moved to Waxahachie, about 30 miles south of Dallas. When she was 7, her father decided he was tired of family life and went to Oklahoma, leaving her mother to raise 13 children. Everyone helped make ends meet by picking cotton and washing clothes—not the kind of life Coleman dreamed about. “If we’re going to better ourselves,” she once said, “we’ve got to get above these cotton fields.”

Frightened at the prospect of field work for a living, she began thinking of ways to escape a depressing future. An extraordinary event on the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk, N.C., changed her life forever. On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright eased into the biplane he and his brother, Wilbur, had built. He opened the throttle of a 12-hp home-built engine and took to the air—the first person to successfully fly a heavier-than-air machine. Tales of daring aerial feats began to appear in newspapers and magazines during the next few years.

Coleman saw in those sensational stories a way to rise above the cotton fields. “I read everything I could get my hands on about aviating,” she later recalled. “Some of the libraries wouldn’t let black girls who picked cotton borrow books, but the books I wanted were about piloting, and folks were so surprised they let me have them anyway.”

Coleman’s first achievement was receiving her high school diploma. She enrolled at Langston Industrial College but could afford to attend for only one semester. Although discouraged, she was determined to succeed in life. She moved in with a brother in Chicago, attended beauty school and worked as a manicurist. Meanwhile, she dreamed of becoming a daredevil pilot like those she read about in magazines.

One flying school after another closed the door and refused to listen when she expressed a desire to become an aviator. The cold-shoulder treatment did not cool her fiery spirit, but Coleman quickly realized she would have to overcome strong racial bias to reach her goal. At that time, it was a well-known “fact” that blacks lacked the aptitude for flying.

Someone told Coleman that France did not care if you were a girl—even a black girl. In 1909, the Baroness Raymonde de la Roche had become the first woman aviator. Two years later, the first woman to earn a license was American Harriet Quimby, who went on to win fame as the first woman to cross the English Channel in 1912. That same year, Katherine Stinson became the first woman airmail pilot. Coleman idolized those aerial pioneers, and they became her inspiration.

Robert Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Weekly Defender, heard about the young black girl who wanted to fly. His queries to various French aviation schools confirmed that color and sex posed no barriers, and he decided to help Coleman get accepted.

Then Coleman realized that she had to overcome yet another obstacle. Although it might be possible for Coleman to attend a flight school in France, it would be futile to attend classes there unless she knew the language. Encouraged by her newfound newspaper friend, Coleman saved money for the trip from her jobs as a manicurist and waitress and still found time to study French at a language school. Within a few months she was ready to leave for France.

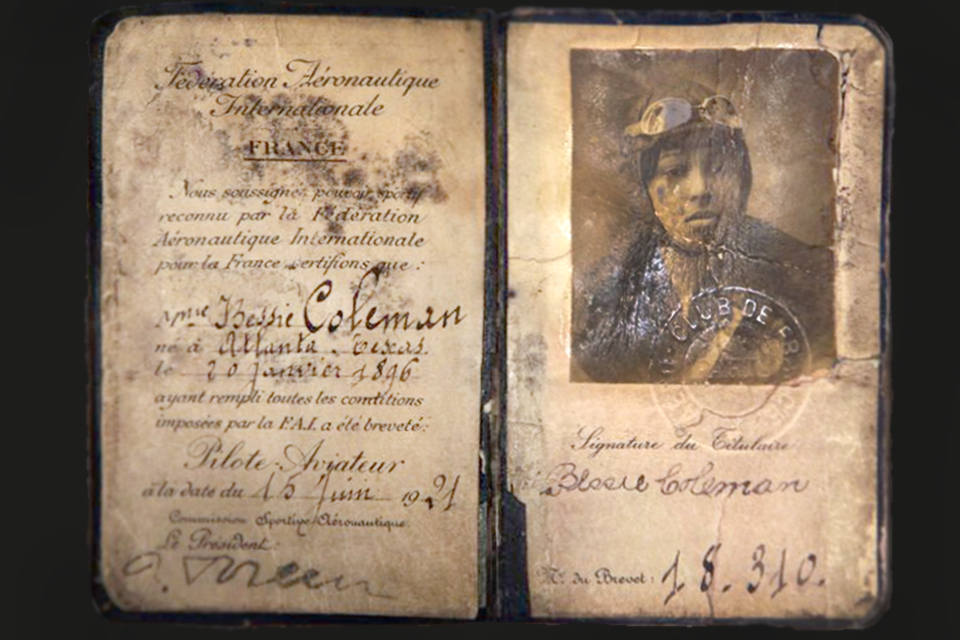

On her arrival, Coleman quickly learned about the dangers of flying. The trainers were frail, unstable machines that were difficult to control. Many of her fellow students had accidents, and some were killed. But nothing could change Coleman’s mind; she had come too far to just quit when the task became more challenging. Ten months later and after much hard work, she graduated as a pilot on June 15, 1921.

Coleman was the only black female pilot in the world when she returned to America with her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. However, her plan to start a flying school for African-American men and women would have to be postponed until she could raise some capital. Coleman was unemployed and had used nearly all her savings while in France. She decided it was time to put her new skills to work as an airshow performer.

During the Labor Day weekend in 1922, a big crowd came to an airshow near Manhattan to see what no American had ever seen before—a black woman flier. And what a pilot she was! Throughout the afternoon, Coleman thrilled observers with loops, figure eights and other precision demonstrations.

Six weeks later she gave another death-defying performance for an enthusiastic crowd at the Checkerboard Airport in Chicago. While doing a figure-eight maneuver, she appeared to lose control of her plane. But it was just part of the act, and the crowd breathed a sigh of relief when she recovered and landed safely.

Fans began calling her “Brave Bessie” and cheered when she appeared in her military-style uniform. Her superb ability made her a star at airshows across the country. As she danced an aerial ballet across the sky, it was obvious that the daring young woman in her flying machine had found a better life high above the cotton fields.

Coleman moved to Houston and began a successful barnstorming career. She was also in demand as a lecturer—captivated audiences listened to vivid descriptions of her adventures. During one airshow, a woman parachutist did not arrive, and the unruly crowd demanded a refund. Coleman knew the show had to go on, so she did the parachute jump herself.

Coleman’s luck ran out one morning in the early 1920s. Her airplane rolled across the ground and rose gracefully into the California sky. Moments later, something went wrong and the aircraft fell back to earth. It was her first accident. Coleman was rushed to the hospital with a broken leg, fractured ribs and other injuries. Reporters hurried to Coleman’s bedside and found her spirits high. She assured them she “would soon be back in the air.”

One year later her broken bones had mended, but Coleman decided to remain on the ground for a time. She moved back to Chicago and began living a quiet life, away from the crowds. She entertained at her home and tried to persuade her famous guests to help establish a flying school. Although they applauded the enterprise, their praise was more generous than their donations.

Eventually, Coleman missed the excitement of flying and began appearing once again in airshows at county fairs and carnivals. She enjoyed being able to sweep the clouds again.

Coleman was invited to perform at the annual Negro Welfare League in Florida in 1926. With William Wills, her mechanic and public relations manager, she took off from Dallas and made two emergency landings before arriving in Jacksonville on April 30. While Wills made repairs to the plane, Coleman went to the restaurant and found a pleasant surprise. Robert Abbott, her old friend who had helped her get into flying school, had come to see her perform.

A check flight was necessary after Wills’ repairs were completed. As Coleman walked toward the plane, Abbott had a sudden premonition and urged her not to fly. She ignored his pleas and told him not to worry. It would be a short hop around the field and everything would be fine. She had promised to give a young college student a ride, and she wanted to get the test out of the way.

Coleman climbed into the cockpit, started the engine and waved to Abbott. Moments later she soared into the clear blue sky and turned the controls over to Wills, who would do the maneuvers. He put the plane into a steep dive at 3,000 feet.

Then disaster struck—the plane flipped upside down, and Coleman fell to the ground. Until this flight, she had always observed all safety rules, but for some reason she had not fastened her seat belt and was not wearing a parachute. Wills tried to move the stick, but it would not budge. He could not bring the plane out of the dive and was killed on impact.

Although Coleman was alive when she was placed in the ambulance, she died that same evening. Later it was found that the accident had been caused by a wrench that had jammed the controls.

Spectators who had come to see Coleman’s thrilling airshow instead paid their last respects to the 33-year-old daredevil. Afterward, her body was returned to Chicago and buried in Lincoln Cemetery. Bessie Coleman’s death ended a promising career. Yet for a few short years she had reveled in a childhood dream that had come true.

Within a few years of her death, Bessie Coleman Aero Clubs became a reality. William J. Powell, one of America’s first black pilots, organized the clubs to help air-minded youngsters fulfill their dreams. The first all-black airshow in America attracted a crowd of 15,000 on Labor Day in 1931, and a flying school for African-American men and women was formed the next year.

A pair of black fliers in Los Angeles made headlines during their flight across America in 1932. James Herman Banning and his mechanic, Thomas C. Allen, bought a used airplane and completed the transcontinental journey in 41 hours, 27 minutes.

Congressional legislation opened the door for African Americans to receive military flight training in March 1941. Reluctantly, the Army Air Corps trained an all-black unit at Tuskegee, Ala. The “lack of flying aptitude” myth was laid to rest when the first class of cadets received their wings one year later. During World War II, the Tuskegee flight school graduated 950 pilots who served in four fighter squadrons and four medium-bomber units. During their 200 missions escorting bombers to heavily defended sites in Germany, the Tuskegee airmen never lost a single bomber. Black fighter pilots earned distinction in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. By 1945 they had shot down 111 enemy aircraft.

President Harry S. Truman signed a document that abolished segregation in the armed forces on July 2, 1948. Although the Air Force spearheaded the integration of blacks into all military vocations, the other services offered career opportunities only later. Black pilots served alongside their white counterparts throughout the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Brigadier General Frank E. Petersen, Jr., became the first black to command a Marine Corps fighter squadron. The first black four-star general, Daniel “Chappie” James was named commander in chief of the Aerospace Defense Command in 1975. Ensign Jessie L. Brown flew combat missions from USS Leyte during the Korean War as the first black Navy pilot. While flying a sortie over mountainous terrain, his plane was hit by enemy fire. Brown made an emergency landing but was trapped in the wreckage of his plane. Rescue attempts failed, and he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Air Force Lt. Col. Guion S. Bluford, Jr., who had flown 144 combat sorties in Vietnam, was the first black pilot in space. As a mission specialist during a seven-day journey aboard Challenger, he helped deploy an INSAT-1B satellite.

Pilot William Powell encouraged black youths to seek careers as pilots, mechanics and designers, and to “fill the sky with black wings.” As he once said, “Because of Bessie Coleman…we have overcome the barriers within ourselves and have dared to dream.”

This feature originally appeared in the November 1998 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe!