George Grosz and Adolf Hitler were equally traumatized by Germany’s defeat—but they coped in wildly divergent ways.

One afternoon in or around 1920, during the nascent days of Germany’s Weimar Republic, artist George Grosz paraded through Berlin with a poster aimed at recruiting “well-built young society girls” for a party at his studio, beginning at 8 p.m. Roughly 100 guests flooded the studio for a rollicking two-day bacchanalia. This and other alcohol-fueled festivities were, Grosz readily admitted, escapes from the trauma and violence that the artist, then in his mid-20s, had experienced throughout the First World War. He called it “contentment and suicide in high style.”

Grosz had voluntarily enlisted, as had a fellow artist four years his senior named Adolf Hitler, because they genuinely considered military service to be an opportunity for artistic inspiration. Growing up in a society that glamorized war, both were utterly unprepared for the unprecedented levels of carnage that new military technology had enabled in the 1910s.

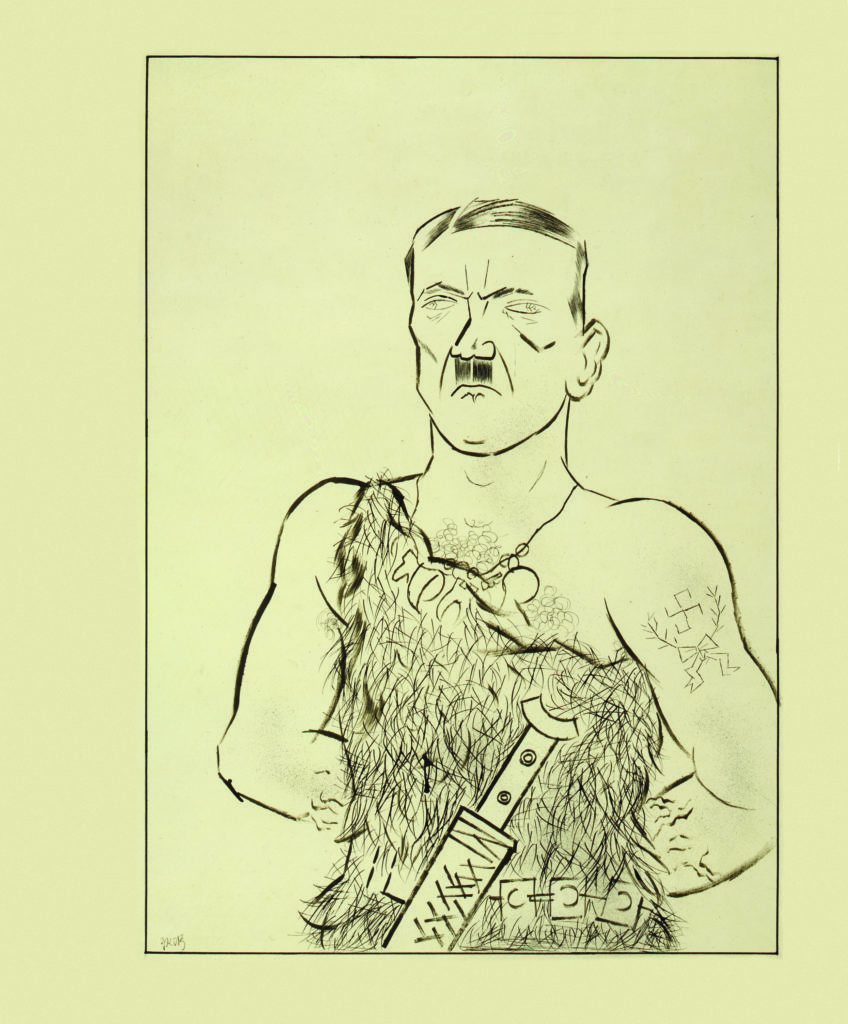

Though Grosz and Hitler were equally traumatized by Germany’s defeat, they coped in wildly divergent ways. Hitler, an aspiring dictator, adopted a pernicious form of nationalism. He diabolically understood in 1919—a full 14 years before coming to power—that quashing the growing cultural diversity in the Fatherland was vital to carrying out his genocidal agenda. By the early 1920s, the failed artist argued that the Nazis should control German culture before attempting military expansion.

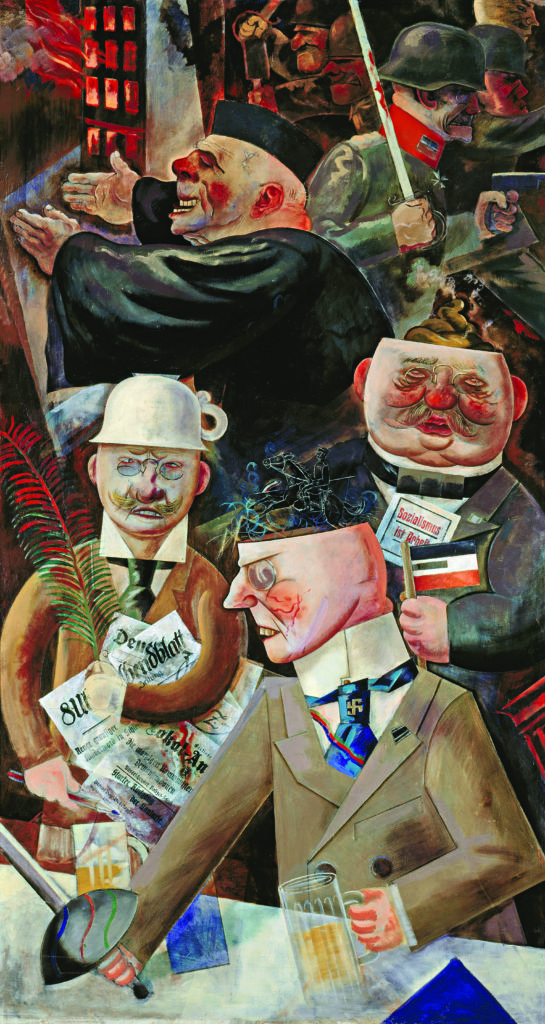

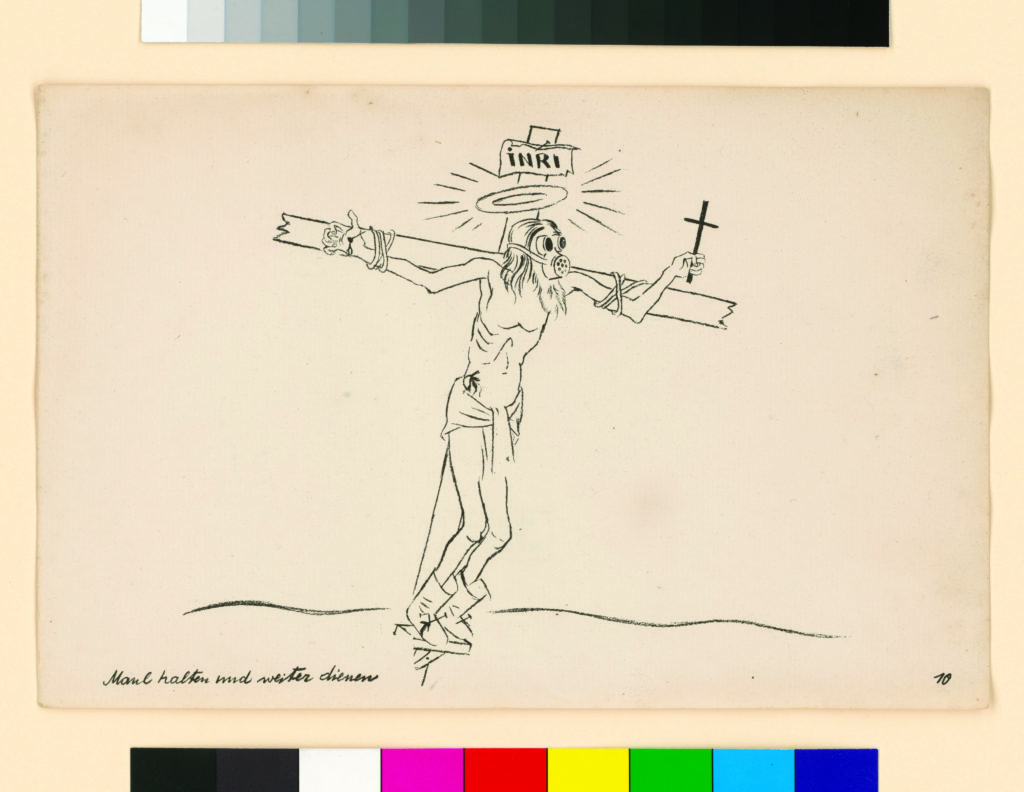

Grosz, however, learned from World War I that the very origins of Germany’s defeat were rooted in bellicose nationalism, and that conquering this would be the key to his nation’s rebirth. Putting his mental health, career, and physical safety at risk, he launched a decade-long crusade in Germany through the most popular method of cultural expression at the time: visual art. Long before Hitler ever did, Grosz became a household name in Germany through his widely published satirical artworks mocking the growing radical right and skewering the government and judicial system as incompetent.

Consequently, though Hitler and Grosz never met, Grosz earned a permanent place in Hitler’s political crosshairs. A few days before Hitler came to power in January 1933, Grosz, his wife, and their children fled to New York after receiving death threats from the Nazis. His instinct to flee, like his social commentary, was on target: a few days after the Führer’s ascent, Nazi hooligans raided his empty home and studio in Berlin.

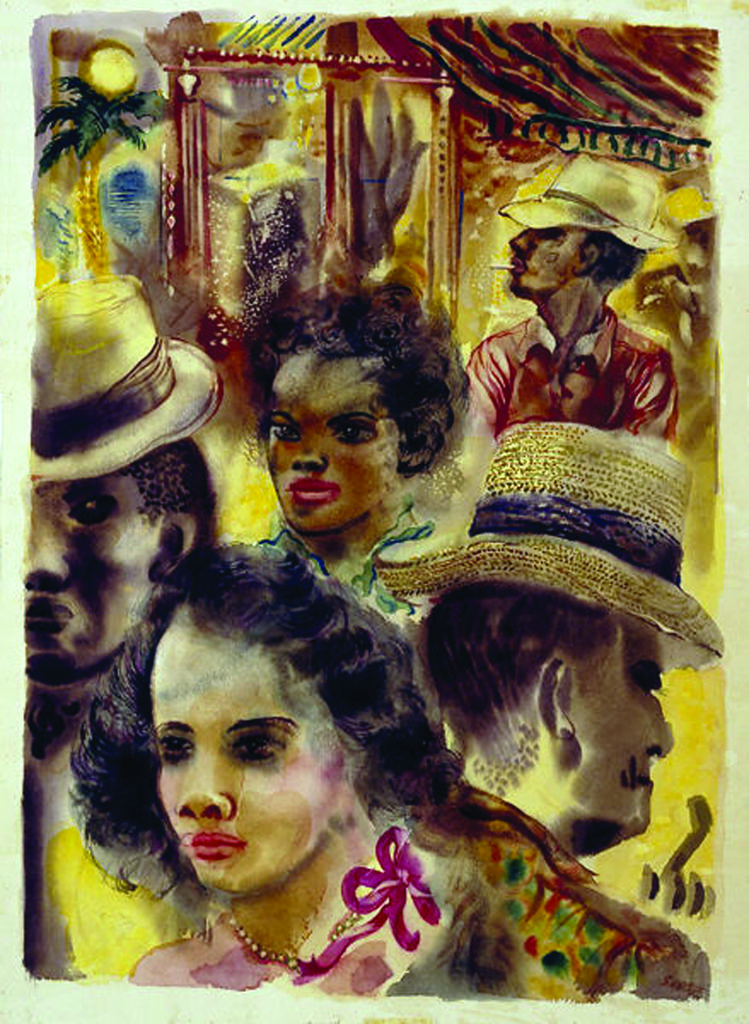

Grosz continued his criticism of the Nazi Party from his new home in the United States. Yet the man who was once the most famous artist in Germany never again regained that renown. After the war he returned to Berlin, but struggled with drinking. In 1959, at age 65, it led to his death there, in the nation he had so vividly tried to warn about the perils of fascist and racist policies. ✯

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of World War II.