When America entered World War II, songwriter Irving Berlin was 53 years old—and desperate to do something for the war effort.

When America entered World War II, songwriter Irving Berlin was 53 years old—and desperate to do something for the war effort.

In the Great War he had staged an all-soldier revue that included his famous ballad to the common soldier, “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” Berlin called General George Marshall, the army chief of staff, and offered to put on a new show to raise money for the Army Emergency Relief Fund and boost civilian morale. Within weeks he was back in an old barracks in Camp Upton on Long Island, spinning out numbers and rehearsing song and dance acts for This Is The Army.

The dancing was a problem. “Where the hell am I going to find a choreographer who’s a soldier in the army?” he complained one day to a producer friend. The producer replied: “They just drafted Bob Sidney.”

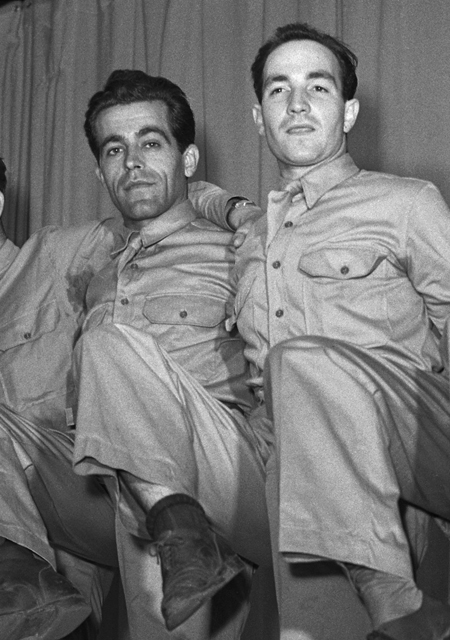

Within days Robert Sidney found himself, to his blessed relief, yanked out of boot camp and assigned to work he knew and loved. A largely self-taught dancer and choreographer, Sidney was 33 years old and had had a few small parts in Broadway musicals. Ironically, it was being drafted into the army that catapulted him to the top of the dance world.

This Is The Army opened on Broadway on July 4, 1942, with a cast of almost 300 show biz pros who had been rounded up from the army’s flood of draftees. The show was corny and a bit dated even by 1942 standards (Berlin’s producer had managed to get him to tone down—but not eliminate—several blackface “minstrel” numbers). It was also a sensational hit that played across the country, raising $2 million for the army fund.

Robert Sidney kept a growing trove of anecdotes about the absurdities of being a dancing master sergeant. In Holly-wood, where the company spent several months producing a film version (starring a young Ronald Reagan), the men were ordered to keep up military appearances by bivouacking in tents and marching each day to the Warner Brothers Studio—though the tents, heated and electri?ed, had been built by the studio’s prop department.

Conditions became much more realistic overseas. The original plan was for the show to disband after a fundraising tour of England. But General Eisenhower saw the show in London and decided that it could do as much to boost the morale of the troops as it had for civilians. For the next two years the performers toured Italy, North Africa, and the Pacific, playing for more than a million GIs while they lived off C-rations and traveled on a rickety freighter.

One performance on the Admiralty Islands was interrupted by Japanese snipers hiding in the woods nearby. They had held their ?re during the musical numbers, but when two comedians started their routine they opened up. “The goddamn enemy is out there shooting at us!” shouted one of the duo as he rushed off stage. Sidney deadpanned, “That’s not the enemy. Those are critics.”

With 14 black performers, the unit was the first—and only—integrated company in the army, and their arrival was often a cause for consternation among local officers; Sidney eventually took on the role of advance man, traveling ahead to arrange everything and gently but firmly insisting that the company bunk and mess together, on General Marshall’s orders.

But the troops who saw the show ate it up; as one of the company recalled, “They thought they were going to see an accordion player and a broad shaking her ass,” and instead got a Broadway revue with full orchestra, acrobats, vaudeville comedians, huge production numbers. The highlight was always Irving Berlin himself reprising “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.”

Sidney went on to become a leading Hollywood choreographer who directed Cyd Charisse, Rita Hayworth, and other stars, and who also had a knack for making actors who were not professional dancers look good. Every ?ve years, the cast of This Is The Army got back together for a reunion, the last time in 1992, the 50th anniversary of the show’s opening.