HEAT WAFTED UP IN SLEEPY SPIRALS from the Sinai Desert on the afternoon of October 6, 1973. Lizards lay about on sun-warmed stones, blinking in contentment. Falcons circled lazily in the pale blue sky. The waters of the Suez Canal lapped gently at its sandy shores. Suddenly, at exactly 2 p.m., this hushed stillness erupted as 2,000 Egyptian artillery pieces, Katyusha rockets, howitzers, and surface-to-surface missiles blasted the canal’s eastern bank, throwing tremendous plumes of sand into the air. Israeli defensive positions years in the making were pulverized in minutes. Without warning, 222 Egyptian MiG and Sukhoi fighters came screaming out of the sky and bombed command posts, surface-to-air batteries, air bases, supply dumps, and radar installations. Simultaneously, a few hundred miles to the north, the rugged hills of the Golan Heights shook with massive explosions as 100 Syrian MiGs attacked Israeli positions and an assault force of as many as 900 tanks and 40,000 infantry crossed into Israeli territory.

The October War had begun. Before it was over, battalions of tanks, hundreds of aircraft, and legions of soldiers would clash in one of the late 20th-century’s most momentous wars. Oil prices would soar to unprecedented heights, and the specter of nuclear war would loom over the battlefield. Though brief—fighting ended within a month—the conflict had enormous impact. It broke a political stalemate and made possible a long Egyptian-Israeli peace that’s unique in the roiling Middle East.

‘I’ll wipe them out with two tanks,’ an Israeli general said

The roots of the fighting in 1973 lay in the Six-Day War of June 1967, when the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) trounced combined Arab armies and took the Golan Heights from Syria, the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and East Jerusalem from Jordan. The so-called War of Attrition followed, with artillery duels, commando raids, air strikes, and diplomatic forays, none of which shook Israel’s grip on its newly occupied territories. Stymied, Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat determined to retake the lost lands with another war. Sadat went to Syrian president Hafez el-Assad, who burned to recapture the Golan Heights. “I’ll be with you,” he told Sadat. Jordan and Iraq agreed to provide a few military units.

Sadat, a talented politician and soldier who had succeeded longtime president Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970, determined he had no choice but to fight. Israel would negotiate on the occupied lands only if threatened militarily, he thought. And he knew that if he made peace without a fight, Saudi Arabia and other rich Arab states would cut off much-needed development aid to Egypt.

SADAT DID NOT SET OUT TO DESTROY Israel. The IDF was too strong, and the United States would never let its ally fall. Rather, he wanted to deliver a blow that would shake the IDF’s sense of invincibility—inflated by its quick victory in the 1967 war—and persuade Israel and its allies that the negotiating table offered the best chance for security. “If we could recapture even four inches of Sinai territory,” he reasoned, “then the whole situation would change—east, west, all over.”

Operationally, Sadat believed he had to hit hard and fast. Once hostilities opened, the United States and the Soviet Union would almost certainly get involved—the Americans to protect Israel, and the Russians to help Syria and maintain its influence in the region. Sadat also assumed the United Nations would insist on a cease-fire. The key, he believed, was to quickly retake as much land as possible to give Egypt a strong bargaining position in negotiations that would undoubtedly follow. “He who wins the first 24-hour encounter,” Sadat said, “will surely win the entire war.”

The Egyptians and Syrians designed a two-front operation, coordinated from Cairo. As the Egyptians stormed across the Suez Canal and occupied part of the Sinai, Syrian forces would move to retake the Golan Heights. Military leaders for the two countries tapped the Soviet Union for help constructing the world’s most formidable surface-to-air defense systems, with SAM-2, -3, -6, and -7 missile batteries. They bought thousands of rocket-propelled grenade launchers and AT-3 Saggers, wire-guided antitank missiles. Soviet T-55s and T-62s were added to the tank battalions, while air power was bolstered by MiG-17, -21, and -23 fighters and Su-7 and -20 fighter-bombers, as well as Scud surface-to-surface missiles.

Egyptian soldiers trained intensely, rehearsing their attack across the Suez at least 35 times with full-scale mockups of Israeli installations. Sadat’s chief of staff, Lieutenant General Saad el-Shazly, focused on what he called “the harshest test”: crossing the Suez Canal, which was as wide as 220 yards in places, and breaking through ramparts that IDF engineers had built on the other side. These mountains of sand topped 60 feet and had slopes of 45 to 65 degrees. To carve out passages for their men and machines, the Egyptians created some 40 engineering battalions equipped with 450 high-powered water hoses.

The Arabs would face an Israeli military feared for its armor and air power. On the ground, IDF forces were headed by well-armored Centurion and M-60 tanks as well as “Super Shermans,” revved-up versions of the World War II classic with 75mm or 105mm high-velocity cannons. In the air, the Israeli Air Force, which totaled 366 craft, boasted of its superb F-4 Phantoms, A-4 Skyhawks, Mirages, and Super-Mystères.

Since the 1967 war, Israel had built formidable defenses for its new territories. The Bar-Lev Line, a chain of fortifications, stretched 100 miles along the Suez, from the Mediterranean in the north to the Gulf of Suez in the south. In the Golan Heights, an intricate network of antitank trenches, firing platforms, and listening posts defended Israeli lands.

The IDF felt secure behind these barriers—perhaps too secure. Before the Egyptian attack, less than half of the Bar-Lev defenses were manned fully. Strutting with confidence after the Arab collapse in the 1967 war, Israel’s military leaders underestimated their foes. “Put all [the Arabs’] paratroops with Saggers on a hill,” one major general crowed, “and I’ll wipe them out with two tanks.” Zvi Zamir, head of Mossad, Israel’s secret service, later admitted: “We scorned them.”

Throughout the summer and early autumn of 1973, Egyptian and Syrian military leaders finalized their plans. They decided to open the attack on October 6, when the Suez Canal’s currents and tides would be optimal for a crossing. This would also be Yom Kippur, the holiest day for Jews. (Historians disagree about whether Egypt deliberately scheduled the attack for this sacred day.) Jews and many in the West refer to the conflict as the Yom Kippur War. Arabs call it the Ramadan War because the fighting opened during the holy month of Ramadan and on the very day when Muslims feast to celebrate the Prophet Muhammad’s victory at the Battle of Badr and his return to Mecca. Indeed, the Egyptians code-named their attack Operation Badr.

Israel remained largely unaware of the Arab plan, thanks to a brilliant campaign of deception. Because the Syrians did little to conceal their military buildup, the IDF was convinced that it was of no consequence. Egypt’s movements seemed little different than its annual autumn military exercises.

To add to the misdirection, Egyptian and Syrian leaders whispered to the press about deep rifts dividing their two countries as Sadat made blustery speeches about a “year of decision” that never seemed to come.

As the Arab buildup began to look like a real threat, some Israeli officials urged a preemptive strike. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister Golda Meir balked, worried that Israel would be seen as the aggressor—a perception that might jeopardize support from the United States. “War is imminent,” Mossad spies reported on October 5, but the head of Israeli military intelligence dismissed the warning. Later it emerged that Jordan’s King Hussein, who feared all-out war, had told Meir of the coming assault. Again, little was done. Dayan and Meir expected an attack, but not the military, political, and economic war that the Arabs had prepared.

THE ATTACK ON THE SINAI OPENED with brutal force and painstaking precision. In the first minute after the 2 p.m. start, Egyptian artillery slammed more than 10,000 shells onto Israeli positions along the Suez Canal. Within 20 minutes, Egyptian MiGs had completed as many as 300 sorties. Dinghies with assault troops sliced through the canal’s waters, the men chanting “Allahu akbar!” (“God is the greatest!”) at each stroke. Engineers deploying water hoses, bulldozers, and explosives blasted some 60 paths through the sand ramparts.

By 5 o’clock, some 32,000 infantry had landed. Within 24 hours, more than 1,000 tanks, 13,500 vehicles, and 100,000 men were safely across the canal. “The whole operation,” Shazly remarked, “was a magnificent symphony played by tens of thousands of men.” Egypt’s losses: just 208 killed.

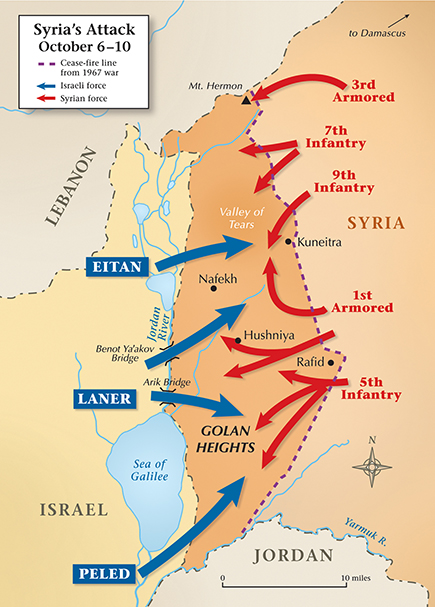

In the Golan Heights, the Syrians looked poised for similar success. They had placed about 1,300 tanks (mostly T-55s), 65 SAM batteries, 400 antiaircraft artillery, and 600 artillery pieces along a 50-mile front. By contrast, the IDF had just 170 tanks and 60 artillery pieces to defend the region.

Geographically, the boundaries of the Golan were roughly marked by Mount Hermon in the north and the Sea of Galilee in the southwest. Syrian forces were to attack in both the north and south, preceded by an air strike. Troops in the north aimed to smash a hole in Israeli lines and then arc down to link up with the southern forces, snapping off the Golan in a pincer movement. In the south, two Syrian infantry divisions were to strike near Rafid, while an armored division broke through Israeli defenses and captured key bridges spanning the Jordan River at Benot Ya’akov and Arik, just north of the Sea of Galilee.

In the north, commandos of the elite 82nd Parachute Regiment initiated the attack, landing on Mount Hermon and capturing a critical Israeli observation post. Fortunately for the Israelis, however, Syrian forces were not the equal of the Egyptians. Their officers failed to bring forward engineering units with the bridge equipment to cross Israeli antitank ditches. A massive traffic jam resulted. As the Syrians sorted things out, Israeli artillery and tank fire from the excellent 188th “Barak” Armored Brigade knocked out their forward units, blunting the advance.

After heavy losses, the Syrians finally crossed the ditches on October 7 and charged furiously at enemy forces positioned on the high ground. The Israelis rained fire upon the infantry in the valley below, cutting them to pieces. Similarly, Syrian armor rushed ahead with no coordination, presenting fat targets for Israeli flanking attacks and artillery fire.

Three days into the fighting, the Syrians in the northern Golan threw more than 200 tanks, additional artillery, and the Republican Guard against some 30 Israeli tanks of the elite 7th Armored Brigade, part of Brigadier General Rafael Eitan’s command. Through skillful counterattacks, this tiny Israeli force confused the Syrians, many of whom abandoned their equipment and fled. High-explosive, armor-piercing shells rent many of the Syrian tanks that stood their ground. Red-orange flames shot skyward, and plumes of black smoke curled into the air from the smashed hulks of more than 500 Syrian tanks and armored personnel carriers, along with 60 to 80 Israeli tanks and other equipment. The attack in the north had been stopped cold in what became known as the Valley of Tears.

In the southern Golan, the Syrians enjoyed some early success. By the end of the first day, their sheer numbers had forced a breakthrough. Though snarled traffic slowed the advance as it had in the north, the Syrians plowed forward, heading for Hushniya, northeast of the Sea of Galilee, and even attempting to take Nafekh, the Israeli command center.

On the second day, Syrian commanders in the south targeted the Benot and Arik bridges—key routes for Israeli reinforcements. But problems soon mounted. A Syrian mechanized brigade ran into a small IDF force of Super Shermans, losing 17 T-55s. A halt was called.

Meanwhile, 35 tanks of a Syrian armored brigade were put out of action before the Arik Bridge just as another mechanized brigade got into a firefight in the same sector. Again, this brigade stopped abruptly. In the late afternoon, 95 Syrian T-62s were advancing virtually unopposed when their commander, for reasons never determined, ordered them to stop as well. Such appalling Syrian command and control—combined with superb Israeli gunnery—doomed the southern operation.

THE SUCCESS OF ISRAELI FORCES IN THE GOLAN was not happenstance. Though the Arab attack surprised them, Israeli leaders reacted swiftly and decided to concentrate forces against the Syrians first; if defenses broke in the Golan, they reasoned, the Syrians would reach inside Israel itself. The Egyptian thrust could be contained in the vast Sinai, a natural buffer, until the Syrians had been halted.

Meanwhile, Egyptian operations in the Sinai were going well. With the Bar-Lev forts silenced, the Egyptians consolidated their position, laying minefields and constructing defensive and interlocking firing positions for their tanks and artillery. The antiaircraft and SAM missile shield covered ground operations, a stinging surprise for the Israeli Air Force, which lost 14 planes in the first two days.

The Egyptians also proved to the doubting Israelis that they had the stomach to fight. Without waiting for air or infantry support, the IDF counterattacked on October 8, sending 300 tanks in a headlong dash against the Egyptians, expecting the enemy to break and run as they had done in previous wars. To the Israelis’ shock, the Egyptians hit them from the front with artillery fire, from the sides with tank assaults, and from behind with infantry wielding Saggers and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. In 48 hours, 200 Israeli tanks were destroyed.

The Egyptians’ will and tactics stunned the Israelis. One Israeli officer recounted how he mistook enemy soldiers atop sand dunes for trees: “One of my tank commanders radioed back, ‘My God, they’re not tree stumps. They’re men!’…Suddenly all hell broke loose. A barrage of missiles was being fired at us. Many of our tanks were hit. We had never come up against anything like this before.”

Major General Ariel Sharon recalled: “These were soldiers who had been brought up on victories….It was a generation that had never lost. Now they were in a state of shock….How was it that [the Egyptians] were moving forward and we were defeated?”

The situation quickly became critical for Israel. In the first four days of the fighting, it lost 49 warplanes and almost 500 tanks. Panic swept through the Israeli government; unless the Egyptians could be turned, the entire country was at risk. In an October 9 meeting with Prime Minister Meir, Dayan discussed using the country’s nuclear arsenal—at least 13 bombs deliverable via Jericho missiles. Unwilling to deploy this ultimate weapon, Meir demanded American help. President Richard Nixon was sympathetic—his national security adviser and secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, believed that the defeat of Israel by a Soviet-armed Syria would be a geopolitical disaster—and approved $2.2 billion in supplementary military aid. The U.S. Air Force launched Operation Nickel Grass, which would airlift some 22,000 tons of jet aircraft, tanks, ammunition, and other equipment to Israel. Another 33,000 pounds of materiel arrived by sea. This was more than military aid; it was life support.

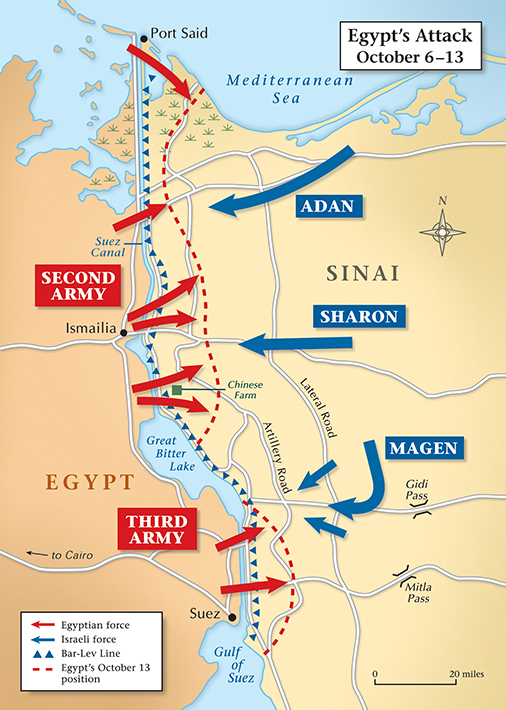

EVEN BEFORE THIS HELP ARRIVED, RESOURCEFUL Israeli commanders changed tactics. Instead of launching head-on assaults, they struck at the enemy’s flanks and used heavy machine guns to knock out infantry armed with antitank weapons. Soon, the Egyptian advance slowed and stopped. But already parts of the army had pushed as far as nine miles into the Sinai. Sadat had won his “four inches of territory.”

At this moment, the war took a dramatic turn as Sadat’s preparations with his allies paid off. Before the war, he had secured an agreement from Saudi Arabia and other oil-producing Arab countries to limit exports to nations that didn’t support the Arab cause. In accordance with that agreement, and with the announcement of Operation Nickel Grass, they now slapped an embargo on oil exports to the United States and Europe.

This rocked world oil markets. During the 1967 war, Arab countries had made a half-hearted effort to stop sales to the West; this time, they fully committed. The price of oil quadrupled to nearly $12 per barrel by 1974. Sadat’s play was geopolitical strategy at its finest; Arab countries for the first time turned their vast oil reserves into a powerful political weapon, a tactic they would repeat for decades to come.

By October 10, four days into the fighting, the Golan Heights was a graveyard of steel. Some 870 Syrian tanks, hundreds of artillery pieces, and thousands of other vehicles smoldered across the rocky ravines strewn with corpses. Sensing that the Syrian offensive had lost steam, the Israelis counterattacked on the 11th. Brigadier General Moshe Peled, commander of the 146th Reserve Armored Division, struck from the south with about 110 tanks and a mechanized infantry brigade, while the 240th Reserve Division under Brigadier General Dan Laner attacked in the center. The Israelis punched a hole in the Syrian line and roared east, taking the Syrians from behind and effectively wiping out an infantry and armored brigade.

With that, almost all the Syrians’ territorial gains were lost. The Israelis now invaded Syria itself, hoping to move within artillery range of Damascus and bring the war home to the Syrian leadership. Virtually unopposed, Israeli warplanes hit strategic sites inside the country. An armored division joined up with the 240th and pushed toward Damascus, while the 146th protected their flanks on the Jordanian frontier.

The Israelis came within roughly 25 miles of Damascus. Retreating before this onslaught, the Syrians made a stand on the second of three defensive lines built in the years after 1967. Fighting on their own soil, they were tenacious. An Iraqi armored division appeared—part of the force promised Sadat before the war—and smashed into the right flank of the IDF’s 240th Armored Division. The Israelis wheeled to deal with this threat, which grew more serious when the Iraqis were joined by an armored brigade sent by Jordan. The Israeli advance halted, but they had recaptured Mount Hermon and now stood close enough to shell Damascus.

AS THINGS FELL APART TO THE NORTH, SADAT felt compelled to order an offensive and press deeper into the Sinai. Shazly, his chief of staff, and other top generals fiercely opposed this move. They remembered how Israeli planes had devastated Arab ground forces in the 1967 war, and they did not want to move the army from under its missile shield. Yet on October 14, as many as 1,000 Egyptian tanks and several mechanized brigades rumbled forward. The targets were two gateways into Israel: the mountain passes at Mitla and Giddi, both at least 30 miles east of the Suez.

This thrust was met by air strikes as well as some 800 tanks led by heroes of Israel’s previous wars—General Avraham Adan and Major General Sharon. The two armored divisions outflanked the Egyptian units and ripped into them, destroying 265 tanks and at least 200 other vehicles. In contrast, only 40 Israeli tanks suffered damage, most of it minor. Worse for the Egyptians, the Israeli assault opened a chink in their lines along the Great Bitter Lake, which lay north of the Gulf of Suez. Adan and Sharon pounced and launched a counteroffensive to bridge the Suez Canal and divide the Egyptian Second and Third Armies on the west bank. Sharon was to boldly move his forces across the canal and push the Second Army north, establishing a corridor for Adan’s men to cross and wheel south, where they would destroy SAM missile launch sites and hit the Egyptian Third Army from the rear.

On October 15 and 16, Sharon’s 143rd Reserve Armored Division crossed the canal on pontoon bridges and established a bridgehead. The Israelis also raced southeast on the Sinai, slamming into the Egyptians concentrated in an area known as the Chinese Farm.

The fighting here was fierce. For four days the Egyptians fought the Israelis off from behind well-prepared defenses but Adan crushed their counterattacks. The Egyptian 25th Armored Brigade, for instance, lost its entire force of armored personnel carriers and 85 of its 96 T-62s while destroying only three IDF tanks.

On October 17 or 18, Soviet officials showed Sadat and General Ahmad Ismail Ali, his war minister, satellite pictures of the expanding bridgehead that Sharon had established on the west bank of the Suez. General Shazly recommended pulling back four armored units from the Sinai to counter the threat. But Sadat, calculating the political need to hang on to Egyptian gains, ruled against a withdrawal.

Three days later, with the Israeli threat deepening, Sadat finally pushed for an end to the war. “I knew my capabilities,” he said later, noting the American aid to Israel. “I did not intend to fight the entire United States of America.” Kissinger flew to Moscow, where he and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev drafted a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for a cease-fire.

Although Egyptian and Israeli officials accepted the truce, fighting continued. The IDF sensed a crushing victory and marched on. Having crossed the Suez through the corridor that Sharon had established, General Adan and his 200 or so tanks raced south, destroying SAM sites and enveloping the 45,000-man Egyptian Third Army.

Some Israelis wanted to destroy the force, which was cut off from food and water supplies. Sadat requested U.S. and Soviet troops to enforce the cease-fire, shrewdly drawing the two superpowers into the fray. When the Americans hesitated, Brezhnev signaled that the Soviet Union was willing to act unilaterally—a message that the United States interpreted as major threat. Kissinger and a special crisis-management team within the White House held an emergency meeting and raised U.S. military forces from Defense Readiness Condition 4 to 3 for the first time since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Ultimately, diplomacy defused the situation, but it was one of the Cold War’s most dangerous moments.

On October 28, Israel, under pressure from the United States, agreed to allow the Egyptians to deliver food and medical supplies to the trapped Third Army. The next day, Syria stopped fighting. A couple of weeks later, on November 11, Egypt and Israel agreed to a cease-fire drafted by Sadat and Kissinger. Syria refused to sign.

IT WAS A MESSY END to a savage war. The armor clashes had been the largest since World War II and remain some of history’s costliest. The casualty counts for Egypt and Syria topped 60,000, with more than 2,000 tanks destroyed. Though Israel saw losses of fewer than 12,000 men, the Arab attacks had delivered a body blow to its military might. By one estimate, the war cost Israel the equivalent of its gross national product for a year. In the Sinai alone, the Egyptians had destroyed 110 helicopters and aircraft, about a quarter of Israel’s air power.

Israel’s psyche suffered perhaps the greatest damage. While the IDF had won militarily, the Arabs had seriously threatened Israel in the war’s opening days and proved its leaders wholly unprepared for war. A special commission fingered top leaders in both the IDF and the intelligence service, and fallout from the war helped push Meir from power in 1974, along with Dayan.

The Arabs still today see the war as a glorious struggle against unfair odds, a grand fight to reclaim lost honor. Calling it “a victory which cannot be erased,” Sadat declared, “Egyptian armed forces have realized a miracle.” The Egyptian president emerged a hero and a political figure with great international influence. He had destroyed the myth of Israeli invincibility, restored national pride, ensured financial support from Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich Arab states, successfully played the superpowers, and set the grounds for Egyptian-Israeli negotiations on the Sinai. He was, said Henry Kissinger, a great man “who had the wisdom and courage of the statesman and occasionally the insight of the prophet.”

In 1977, Sadat visited Israel—previously unthinkable for an Arab leader—and made a landmark proposal for peace. This led to the 1978 Camp David accords, brokered by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, and a treaty the next year through which Egypt regained the Sinai and the Suez Canal and made peace with Israel. For this bold action, Sadat and Israeli leader Menachem Begin were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. (Carter won the Nobel the next year for his overall efforts on peace.)

Even as the world cheered Sadat, many Arabs branded him a traitor for not linking peace with Israel to a larger settlement that included the rights of Palestinians and the return of other Arab lands conquered by Israel in 1967. In 1981, radical Islamists assassinated him during a military parade celebrating the October War.

Impressive in scope, unique in execution, the October War stands as one of the most influential conflicts of the second half of the 20th century. The last of the great Arab-Israeli wars, it was the first international conflict where oil was pivotal. It heralded a new order not only in the Middle East but also in the global political and economic system.

MHQ contributing editor O’Brien Browne writes frequently on military history and world affairs and blogs for the Huffington Post. He lives, writes, and works in Europe and the United States.

.jpg)