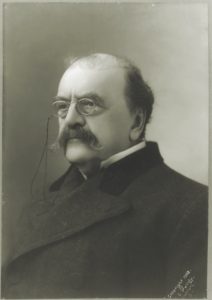

Union general Daniel E. Sickles felt that he got no respect for his role in the Civil War’s pivotal battle. So he decided to go on the offensive.

At 6:30 p.m. on July 2, 1863, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, a Confederate solid shot hurtled through the air and struck Union major general Daniel E. Sickles’s right knee, leaving the lower half of his leg hanging in shreds. Sickles and members of his staff had been riding behind Abraham Trostle’s barn to escape the rain of enemy metal. Sickles, by one account, calmly leaned forward and lifted his right leg out of the stirrup and over the saddle. Helped from his mount, the wounded commander was placed on a stretcher, and his men quickly turned their sweaty handkerchiefs into makeshift dressings and tightened an improvised tourniquet above his shattered knee.

Sickles’s encounter with the cannonball came just as Confederate attacks were beating back the units under his command. Now, with both his right leg and his vaunted III Corps smashed, Sickles, fortified by brandy and a fat cigar, was jolting to the rear in an army ambulance.

The Battle of Gettysburg marked the end of Sickles’s active military service. But he would spend the rest of his life trying to win his place in history as the man who won the Civil War’s most famous battle.

Daniel Edgar Sickles, born into a well-to-do New York City family in 1819, became a lawyer and was elected to the New York State Assembly. Soon after his 32nd birthday he married Teresa Bagioli, a vivacious and coquettish 16-year-old, and the following year President Franklin Pierce appointed him secretary of the U.S. legation to the Court of St. James. When he returned from England in 1856, Sickles was elected to the New York State Senate.

That same year Sickles was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was a powerful Tammany Hall Democrat with his eye on the White House, but in 1859 that dream evaporated when he murdered his young wife’s paramour, Philip Barton Key II (a district attorney and the son of Francis Scott Key). Sickles’s defense team won him an acquittal using the first-ever “temporary insanity” plea.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles, who was desperate to restore his public image, raised the New York Excelsior Brigade, becoming its brigadier general in September 1861. In the spring of 1862, the Excelsiors were merged into Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac—as the 2nd Brigade of Brigadier General Joseph Hooker’s 2nd Division of the III Corps—and Sickles, despite his lack of combat experience, commanded his brigade in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days’ Battles outside Richmond, Virginia. Nominated for a promotion to major general in November 1862, Sickles led the 2nd Division at the Battle of Fredericksburg. In January 1863, when Hooker was elevated to army command, Sickles was tapped to lead the III Corps.

The following spring, at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Hooker suffered a humiliating defeat by Confederate general Robert E. Lee, who soon launched a second invasion of the North. Shifting west from Fredericksburg, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia moved into the Shenandoah Valley and tramped north. By late June all of Lee’s troops—at least 75,000 men—had crossed the Potomac River.

Hooker reacted quickly, keeping his Army of the Potomac between Lee’s forces and the Federal capital, but resigned when he was denied use of the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. His replacement, Major General George G. Meade, soon learned that Lee’s army was scattered across central Pennsylvania. On July 1, with about 97,000 men—all eight corps of his army—north of the Potomac, Meade issued a plan that featured a formidable defensive position in north-central Maryland, behind Pipe Creek, where his forces could retreat if defeated.

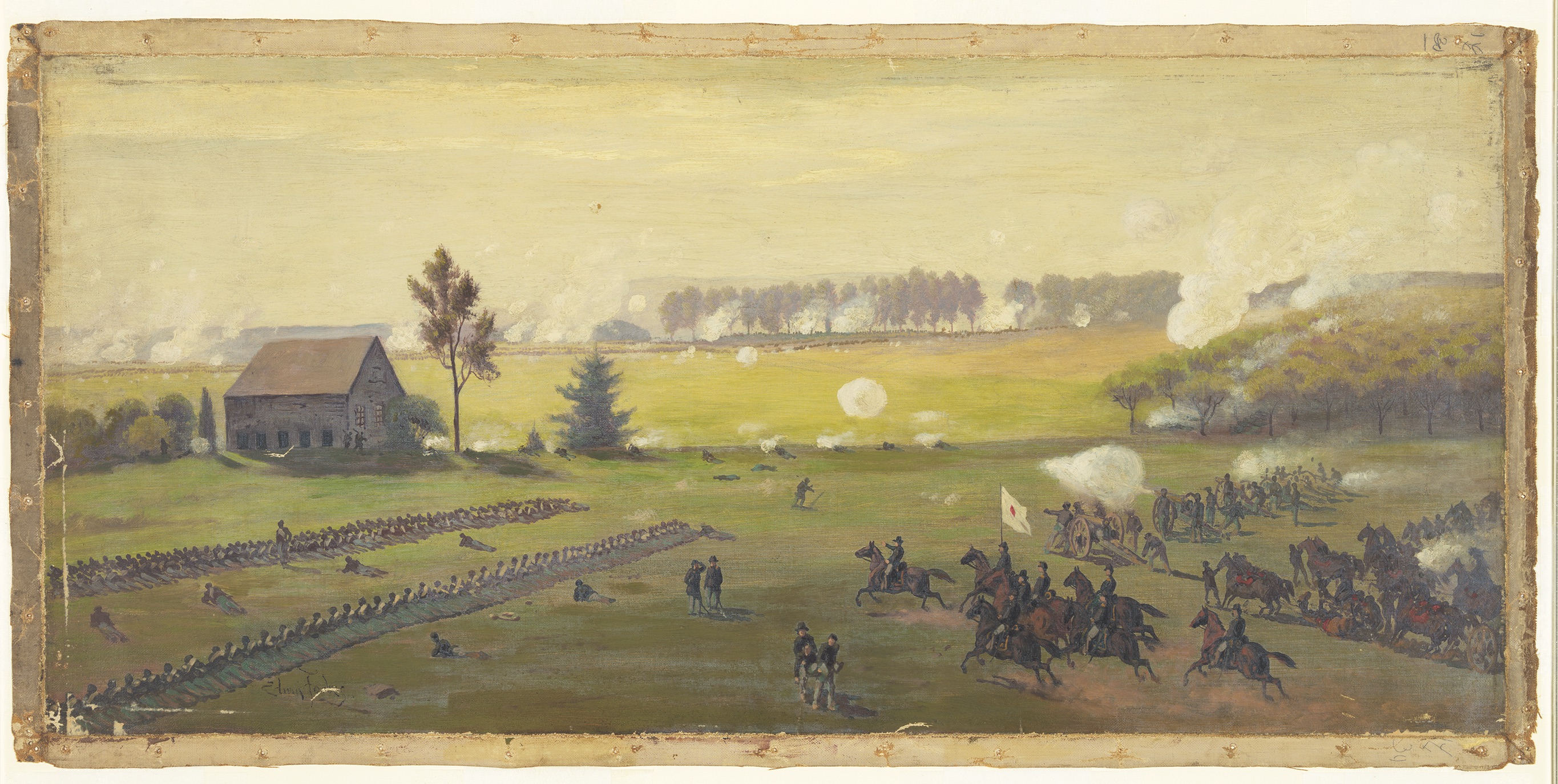

On the morning of July 1 fighting erupted in south-central Pennsylvania, northwest of Gettysburg. Both commanders ordered their forces to the small crossroads town where nine roads converged. By midmorning on July 2, all the elements of Sickles’s two III Corps divisions under Major General David B. Birney and Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys—six brigades of infantry and five attached artillery batteries—had reached the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, two miles south of Gettysburg.

That morning, after riding along his lines before sunrise to assess the situation, Meade had assigned the northern portion of Cemetery Ridge to the II Corps. Sickles was directed to occupy Cemetery Ridge from the II Corps’s left to Little Round Top, which he was also to occupy “if practicable.” A division of Union cavalry posted along the Emmitsburg Road shielded this assigned III Corps line.

As ordered, Birney’s and Humphreys’s divisions took up defensive positions on Cemetery Ridge. But Sickles was concerned, even fretful, about his battle line. At 11

a.m. he rode to Meade’s headquarters at the Leister House, behind Cemetery Ridge, to report his perplexity and request that an army staff officer ride back with him. Trotting south from Leister’s, Sickles told Brigadier General Henry Hunt, the chief of artillery, that he considered his Cemetery Ridge position untenable and wanted to advance his corps three-quarters of a mile to the Emmitsburg Road. “Not on my authority,” Hunt replied. But Hunt did point out the new line’s disadvantages: It was longer than Sickles’s current position, and the III Corps, with only 10,600 officers and men, couldn’t man it. After suggesting that Sickles dispatch a reconnaissance force to the intended new position, Hunt galloped off to get instructions from Meade.

Following Hunt’s advice, Sickles threw forward 300 men under Colonel Hiram Berdan. But when he learned that the cavalry screen had been removed and word came back from Berdan that Pitzer’s Woods beyond the Emmitsburg Road was teeming with Confederates, Sickles decided to advance the III Corps. It was shortly after 2 p.m.

Birney’s division now held the left of Sickles’s V-shaped position while Humphreys’s division, on the right, filed in along the Emmitsburg Road. Artillery bolstered the new line. In occupying the ridge, Sickles committed one of the war’s most stupendous blunders: He’d created an extremely isolated and fragile salient. Vulnerable to attack from two directions—south and west—this new line also left Little Round Top undefended.

Shortly after 3 p.m. Meade rode to the III Corps lines, where Sickles immediately briefed him on the new position. Meade exploded. Why had his orders been ignored? Why had Sickles occupied this forward position? Expressing his regret, Sickles asked if he should pull back. A semicircular eruption of Confederate artillery fire, however, cut the confab short. Meade ordered Sickles to remain. The army commander would send reinforcements.

Shortly after 4 p.m., Confederate infantry assaults began landing like hammer blows. A costly fighting withdrawal brought the III Corps—minus more than 4,200 casualties, nearly 40 percent of its men—back to the position it had originally been ordered to defend. Ten of its regiments had been cut in half.

Sickles’s right leg was amputated the afternoon of July 2. He saved his leg bones and later donated them—placed in a coffin-shaped box along with a card reading, “With the compliments of Major General D. E. S.”—to the Army Medical Museum in Washington. He reportedly visited the bones every year on the simultaneous anniversary of their amputation and the fight for “Sickles’s Salient.”

During Reconstruction, Sickles commanded several Southern military districts. Appointed colonel of the 42nd U.S. Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps) in 1866, he retired in 1869 with the rank of major general to become the U.S. minister to Spain, and he later served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

But what most consumed Sickles after Gettysburg was his vitriolic campaign against Meade. Sickles felt that Meade, among others, had mistreated and dishonored him. Meade’s after-action report, for example, said that Sickles had advanced “not fully apprehending” his instructions. And it was rumored that, had Sickles not been severely wounded, Meade would have court-martialed him. General in Chief Henry Halleck’s Gettysburg report concluded that Sickles’s advance “nearly proved fatal in the battle.”

In February 1864, testifying before the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, Sickles belittled Meade’s command ability. He claimed that his own arrival on the Gettysburg battlefield had stabilized the army. He said he hadn’t received orders from Meade—a flat-out lie—and in frustration had advanced to stop the enemy from occupying commanding ground.

Sickles continued to attack Meade throughout his life. In speeches and in the newspapers, he said that even as late as July 2, 1863—when Meade was perfecting his strong defensive position—the army commander was actually intent on retreating to Pipe Creek, but the fighting along Sickles’s front convinced Meade to stick it out. Sickles also claimed—amazingly—that because his salient had absorbed the shock of the powerful Confederate attacks, he had saved the army’s left flank. He’d won the Battle of Gettysburg. Indeed, many since then have agreed.

But in The Gettysburg Campaign, written in the 1960s and still considered one of the finest accounts of the battle, noted Civil War historian Edwin B. Coddington set the record straight. Sickles was certainly aggressive, he acknowledged, “but as a leader his weakness was his inability to take advice or consider other points of view….[He] conjured up an interpretation of the battle which many historians have taken seriously or accepted outright.” Was Meade planning to fight at Gettysburg? Of course, answered Coddington; it’s obvious from the positions he took up. Had Meade issued orders to Sickles? Yes, he had; he’d “ordered him specifically” to occupy the southern portion of Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top, if possible. Had Sickles won the Battle of Gettysburg? That claim, Coddington concluded, was pure bombast: “When he moved his forces without reference to the others,…Sickles put the safety of the whole army in jeopardy.”

In 1886, when the New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg was created, Sickles was appointed its chairman. Charged with placing monuments to the numerous New York units engaged there, the commission also oversaw the writing of a history of the battle, which naturally approved of Sickles’s July 2 maneuver. For the 30th anniversary of the battle in 1893, Sickles, as “President of the Day,” delivered an address that, in part, attacked Meade, who had died in 1872.

Sickles also had a role in establishing the modern-day park at Gettysburg. In December 1894 he introduced legislation to authorize the federal government to purchase some 800 acres to be designated “Gettysburg National Military Park,” and President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law the following year. Three years later he was awarded the Medal of Honor. The citation lists his “most conspicuous gallantry” on the Gettysburg battlefield.

In 1913, on the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, Sickles toured the battlefield with Joe Twichell, the former chaplain of the Excelsior Brigade. When his old comrade in arms observed that virtually all the battle’s other senior generals had been memorialized with monuments, the feisty New Yorker supposedly shot back, “The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles.”

Sickles died the following year and was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Rick Britton, a historian and cartographer, lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Behind the Lines | The Antihero of Gettysburg

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!