When 31-year-old Douglas Groce Corrigan took off from Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field on July 17, 1938, in a modified Curtiss Robin, he carried two chocolate bars, two boxes of fig bars, a quart of water and a U.S. map with the route from New York to California marked out. Corrigan, who had spent three years trying to get permission to fly from New York to Dublin, had been told that he could fly nonstop from New York to California, but an ocean crossing was out of the question. It was a foggy morning. Corrigan flew into the haze and disappeared. Twenty-eight hours later, he landed in Dublin and instantly became a national hero.

Texas-born Douglas Corrigan had flown for the first time when he was 18, taking a 10-minute sightseeing ride in a Curtiss JN-4D Jenny at a Los Angeles airfield operated by B.F. Mahoney and Claude Ryan. The ride, which cost him $2.50, changed his life, setting him on a course that would lead to disappointment, danger, excitement, fame and even a movie deal. Although he had hoped to become an architect, after that 1925 flight his dreams changed.

He went back to the airfield a week later and took a flying lesson. After that, he started going to the field every Sunday, taking a lesson and then hanging around for the rest of the day, helping the mechanics.

Corrigan first soloed on Sunday, March 25, 1926. He later said that he looked back on that Sunday as the most important day of his life.

Ryan and Mahoney soon closed down their operation in Los Angeles and opened Ryan Aeronautical Company in San Diego, where they offered young Corrigan a job. When he arrived, it seemed as though the factory’s future was pretty shaky. The building contained half a dozen unfinished airplanes–unfinished because the orders for them had been canceled. Then a telegram arrived from Charles A. Lindbergh, who wanted to know if Ryan Aeronautical could build a plane capable of transatlantic flight. Ryan and Mahoney responded that they could have such an aircraft ready within two months, and it would cost about $10,000. Lindbergh liked the price as well as the time frame. He headed for San Diego to check out the Ryan factory.

In February 1927 Corrigan saw Mahoney talking to a tall young man. Corrigan, along with a mechanic, was sent out to the field to get one of the aircraft started so that the lanky youngster could test-fly it.

As they were walking out to the plane, the mechanic explained, ‘This is that fellow from St. Louis that wants to fly from New York to Paris.’ Corrigan glanced back at Charles Lindbergh and said: ‘Gosh, he looks like a farmer. Do you suppose he can fly?’

They started up a Ryan M-1, but Corrigan didn’t think the engine sounded very good. ‘That’s all right,’ said Lindbergh, and he promptly climbed into the plane. He took off, flew around the field for a few minutes, headed upwind and did nine consecutive loops, finishing up with a wingover. Watching him, Corrigan and the mechanic agreed that Charles Lindbergh could, in fact, fly. And Lindbergh decided to have Ryan build Spirit of St. Louis.

During the two months it took to construct the aircraft, designated the NYP by Ryan, Corrigan and the rest of the crew often worked well past midnight. Corrigan himself assembled the wing and installed the gas tanks and the instrument panel. Lindbergh also spent a considerable amount of time at the factory, supervising the construction.

Corrigan later recalled that everyone at Ryan Aeronautical seemed motivated by Lindbergh and his goal. Apparently, Lindbergh was equally impressed with his new associates, writing of the Ryan crew, ‘They’re as anxious to build a plane that will fly to Paris as I am to fly it there.’

Ryan managed to meet Lindbergh’s deadline, completing the aircraft in time for him to fly Spirit of St. Louis from San Diego to St. Louis in May 1927, and then to New York City. From there, of course, he set off for Paris.

Corrigan and his co-workers went wild when the news reached San Diego that Lindbergh had made it to Paris. The workmen jumped into their cars and drove through the streets of the city, shouting like madmen. But Douglas Corrigan was more than ecstatic–he was inspired. He decided then and there that he wanted to fly across the ocean.

Ryan Aeronautical had built what was now the most famous plane in the world, and all of a sudden business was booming. The factory moved to St. Louis in October 1928, but Corrigan stayed in California and got a job as a mechanic for a new flying operation called the Airtech School, run by the San Diego Air Service. Once it got started, the Airtech School was busy with more than 50 students in training each day. The only chance Corrigan got to fly was on his lunch hour.

He loved doing stunts, especially chandelles–steep, climbing turns–that he would start as soon as the plane was off the ground. Corrigan would often do 10 or 11 chandelles in a row. The company pilot thought he was crazy; when Corrigan stepped out of the plane, the other flier would read him the riot act. Corrigan would just look surprised. ‘I didn’t think it was dangerous,’ he would say, smiling innocently.

But the company pilot won out, and Corrigan was forbidden to do stunts in the company planes. Corrigan subsequently stopped stunting near the airfield. Instead, he flew down to a small field near the Mexican border and did stunts there.

Corrigan went to New York with a friend in 1930, working at Roosevelt Field for a while and barnstorming along the East Coast. He and his partner would land near a small town and talk people into buying airplane rides. Business was pretty good–they sometimes took in as much as $140 a week.

When Corrigan decided to go back to California in 1933, he started looking for a plane in which to make the trip–a cheap one, since he didn’t even own a car. He soon found a Curtiss Robin priced at $325. ‘It looked pretty good, and flew all right,’ he said. He started out for the West Coast a few days after buying the plane. He would stop every 100 miles or so and pick up passengers when he could find them, in order to make a little money while he was traveling.

Once, when he was running low on gas, he passed over several towns without finding a field that looked good enough for a landing. He finally came down in a field that was overgrown with brush. It was a rough landing–one of the wheels hit a tree stump, damaging the landing gear.

Luckily, there was a farmyard nearby. Corrigan walked over, found a few pieces of wood and cut some wire off a fence–all he needed for some quick repairs. He borrowed some gasoline from a farmer’s tractor and flew on after his repair work was completed.

Corrigan returned to San Diego and worked in an aircraft factory for a while, but that did not satisfy his zest for adventure. He decided to refurbish his Curtiss Robin and pursue his dream of flying across the Atlantic. He knew that attempting such a flight might kill him–but he was sure it certainly would not be boring. Since he was Irish American, Corrigan naturally chose Dublin as his destination.

He bought a new engine for his plane–a Wright J6-5 with 165 horsepower and five cylinders. He also built and installed the extra gas tanks that he would need if he were to attempt a transatlantic flight. As far as he was concerned, Douglas Corrigan was all set to be the first man to fly nonstop from New York to Dublin. But it was not to be that simple. When a federal inspector checked out the plane, he licensed it for cross-country flights only.

But Corrigan refused to give up. In 1936, he flew to New York, stopping over at St. Louis on the way. Then he wrote to the Federal Bureau of Air Commerce, asking for permission to go ahead with the flight. For no apparent reason he was told to wait until the following year. Then he was told that he would need a radio operator’s license to make the flight–even though his plane had no radio.

He went back to California, got the license and installed two more gas tanks for good measure. The next year, 1937, he reapplied for permission to make the flight, but Amelia Earhart had disappeared over the Pacific just a few months earlier, and nobody in Washington wanted to give the go-ahead for another solo ocean flight at that juncture. Worse yet, the government even refused to renew the license for Corrigan’s plane, which meant that he would not be able to fly anywhere. ‘It looked like I was stopped now for sure,’ he later wrote.

But the pilot was not completely out of options. Although he had been denied permission to fly, he still had his plane. ‘They can’t hang you for flying a plane without a license,’ he figured. ‘Columbus took a chance, so why not me?’ He flew toward New York, planning to head for Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn. He thought perhaps he could land by night, after the officials had gone home. Then he could fill his gas tanks and fly across the ocean–damn the torpedoes!

In preparation for his great adventure, Corrigan gave his plane a name. ‘I had always considered my plane as a little ray of sunshine,’ he said, ‘so now I put the name Sunshine on the cowling.’

The flight to New York did not go well, however. Bad weather forced Corrigan to land in Arizona the first day. More bad weather forced him to land in New Mexico the next day. The pattern continued throughout the trip. It took him two days just to get across Texas. Corrigan was forced to land in open fields, near various towns that nobody flies to on purpose, including Arkadelphia, Ark.; Ezel, Ky.; and Buckhannon, W.Va. It took him nine days to make it from California to New York.

By then it was the end of October and getting cold. Corrigan decided not to risk an ocean flight. Offending bureaucrats was one thing, but facing the cold skies of the North Atlantic could be quite a bit more dangerous. And the trip Corrigan planned would be dangerous enough in good weather.

He decided instead to try flying nonstop back to California. Corrigan landed at Floyd Bennett Field one afternoon, filled his gas tanks and took off again. No one stopped him, and no one said anything about the plane being unlicensed. He soon had reason to be thankful he had not tried an Atlantic crossing. Even over Mississippi, it was so cold that ice began forming on the carburetor. That caused the engine to slow down, and Corrigan had to keep moving the throttle back and forth in order to break the ice loose and keep it from forming again.

The winds were against him, too, which meant he did not have enough gas to make it nonstop to Los Angeles. He did reach California, though, landing at Adams Airport, in the San Fernando Valley. That’s where the feds caught up with him. An inspector saw the plane and told the airport officials not to let Corrigan fly it. Sunshine stayed in the Adams hangar for the next six months.

Corrigan, however, had no intention of staying on the ground that long. He visited most of the airfields around Los Angeles and managed to get in some flight time in other aircraft. But since he also wanted to fly his own plane again, he overhauled the engine and had the plane inspected.

The federal inspector who came to examine Sunshine after that said it was good enough for an experimental license. Corrigan received permission to make a nonstop flight to New York, and then–if he made it–a nonstop flight back to Los Angeles.

To prepare for the trip, Corrigan ran some tests on gasoline consumption at various speeds, eventually deciding that 85 mph was the best speed for his Curtiss Robin. Then he watched the weather.

Corrigan took off from Long Beach on July 7, 1938. He hit turbulence while crossing the desert and flew over a dust storm in New Mexico. Next came rain squalls with enormous lightning bolts. Since he did not want to use up extra gasoline flying around the storm, he flew straight into it. Fortunately, the gamble paid off. He reached clear air an hour later.

The main gas tank developed a leak toward the end of the trip, and Corrigan wasn’t sure if he would be able to make it nonstop after all. But he was determined to keep flying until the gas ran out. He opened the cabin windows and stuck his head out–partly to keep awake and partly to avoid the fumes.

By that time he was down to the last tank of fuel, and he could only guess how much was left in it. But he kept going. He was able to catch a tailwind near Philadelphia, and by sundown, he made it to New York and landed at Roosevelt Field. He had only four gallons of fuel left when he touched down.

After Corrigan looked over the plane, he decided not to do anything about the gas leak, since it would have taken him more than a week’s work to remove the tank and make the repairs. He was eager to get going on his dream flight. His flight plan was filed–New York to California, just as his license said. And the only map he had was of the United States. On July 16 he flew to Floyd Bennett Field and filled his tanks with gasoline. At 4 o’clock the next morning, he was ready to go.

Corrigan started the plane himself on July 17 and then took out a flashlight to look at the engine and make sure it was running OK. It looked and sounded good, so he climbed into Sunshine and took off, heading east on an eastwest runway.

The plane was so weighed down with fuel that it traveled 3,200 feet down the runway before leaving the ground. When it passed the eastern edge of the airfield, it was only 50 feet above the ground. Not long after that, it disappeared into the fog, heading east.

Corrigan had been flying east for 10 hours when his feet suddenly felt cold. The leak in the main gas tank had gotten worse, and gasoline was running all over his shoes and onto the floor of the cockpit. He was somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean at that point–and he was losing fuel by the minute.

He flew on through the darkness. Time was not on his side, and the leak was getting worse. Before long, there was gasoline an inch deep on the cockpit floor. Just losing the gas was bad enough, but Corrigan was worried that it would leak out near the exhaust pipe–and he was well aware that he had no chance of surviving if that happened.

He knew he had to do something about the leak, but he did not have much to work with. He had only brought a screwdriver with him. With it, he punched a hole in the floor. The gasoline trickled out–on the side opposite the exhaust pipe. He was still losing fuel, but at least the plane was not likely to explode.

Although it was impossible for him to fix the leak, Corrigan kept trying to think of some way to compensate for it. The problem had not been nearly this bad on his cross-country flight, and he had just barely made it to New York. And on this trip there was no place to land if his gas ran out.

He had planned to conserve fuel by running the engine slowly, but now he realized that that would only give the fuel more time to leak out. He decided to run the engine fast instead, using the precious gasoline while he had it. He boosted his rpms from 1,600 to 1,900, then maintained that speed for the rest of the trip.

Corrigan flew straight ahead, hoping he would have enough fuel to reach land. When he saw a fishing boat, he went down close to the water and flew past it. Corrigan realized it was unlikely that such a small boat would be very far from shore. It looked like he was going to make it, and he opened a package of fig bars to celebrate.

He had finished the cookies and started on a chocolate bar when land came into sight. Sometime later, he recalled, ‘I noticed some nice green hills.’ It was not long before he reached Baldonnel Airport, in Dublin, landing on July 18.

Corrigan had achieved his dream, but he was not sure how much it was going cost him. He had broken the rules, after all–and he realized that how he played things from here on out would probably determine how he was going to spend the next few years.

The first person Corrigan met was an army officer. Corrigan introduced himself saying, ‘I left New York yesterday morning headed for California.’ He added, ‘I got mixed up in the clouds, and I must have flown the wrong way.’ The officer responded, ‘Yes, we know.’ Corrigan was surprised, ‘Really?’ he said. ‘How did you find out?’ The officer replied: ‘Oh, there was a small piece in the paper saying someone might be flying over this way. Then we got a phone call from Belfast saying a plane with American markings had passed over, headed down the coast.’ A customs official in a blue uniform came up and asked Corrigan if he had landed anywhere else. ‘I did pass over a city–I guess it must have been Belfast,’ explained Corrigan. ‘But I didn’t see an airport there. This is the first place I’ve landed since leaving New York.’

‘That makes it easier for us, then,’ said the customs agent amiably. They led Corrigan into the field office, where he signed the airport register. Then they showed him the newspaper article, which talked about an unknown pilot who had disappeared over the Atlantic.

Corrigan not only did not have permission to make the flight, he had neither a passport nor entry papers. The officials were not surprised. The officer said he would call the American minister, Stephen Cudahy. ‘Why don’t you come down to the barracks and have a spot of tea while we’re waiting?’ suggested the officer. Corrigan gladly accepted the invitation.

When Cudahy was ready to see him, the customs man was reluctant to let Corrigan go. ‘I haven’t heard from my superiors yet,’ he objected. ‘Why don’t you wait around awhile longer?’ The officer spoke up: ‘What’s the matter? You’re not putting him under arrest, are you?’ The customs man seemed confused. ‘No, but this never happened before,’ came the response. ‘I don’t know what to do.’ The officer just laughed, and he and Corrigan left.

When they met with Cudahy, the American minister wanted an explanation as to how Corrigan ended up in Ireland. Corrigan knew this was a key moment. He smiled and explained that he had taken off from Floyd Bennett Field–heading east. ‘It was a very foggy morning,’ he pointed out. ‘I see,’ said Cudahy dryly.

Corrigan went on to tell the same story he later told in his autobiography. He explained that the plane was so weighed down with fuel that it would not climb fast enough, so he had decided to fly east for a few miles and burn off some fuel before he turned around. He also said his main compass was broken–the liquid had somehow leaked out, and he had had to use a backup compass.

‘Couldn’t you see anything below you?’ asked Cudahy. ‘It was just too foggy,’ responded Corrigan. ‘At one point there was a break, and I could see a city. I figured it was Baltimore–which would have meant I was on course for California.’ The city had actually been Boston.

That was the only break in the clouds he had seen, Corrigan said. He spent the rest of the flight navigating by compass alone. When he finally emerged from the clouds 26 hours later, he saw only ocean. ‘That was strange, as I had only been flying 26 hours and shouldn’t have come to the Pacific yet,’ he said. ‘I looked down at the compass, and now that there was more light I noticed I had been following the wrong end of the magnetic needle on the whole flight. As the opposite of west is east, I realized that I was over the Atlantic Ocean somewhere!’ So he just flew on from there. Finally, he saw a city below him, and he noticed that the airport was marked Baldonnel. ‘Having studied the map of Ireland two years before, I knew this was Dublin.’

Cudahy was skeptical. ‘It was hazy when you took off, was it?’ he said. ‘Well, your story seems a little hazy, too–now come on and tell me the real story.’

‘I’ve just told you the real story,’ replied Corrigan. ‘I don’t know any other one.’

‘So you’re sticking to that story, are you?’

‘That’s my story,’ said the pilot, ‘but I sure am ashamed of that navigation.’

Word of Corrigan’s daring flight quickly spread. The area around the American legation was swarming with reporters, photographers and newsreel cameramen by that evening. Congratulatory phone calls, telegrams and cablegrams started pouring in for the pilot–many from friends, but others from famous folk such as Henry Ford and Howard Hughes.

Corrigan met Eamon De Valera, Ireland’s prime minister, the next morning and told his story once again. When he got to the part about misreading the compass, everyone started laughing. ‘From then on everything was in my favor,’ Corrigan later wrote. ‘He came into this country without papers of any kind, why, we’ll just let him go back without any papers,’ said De Valera. Corrigan said, ‘Gee, Mr. De Valera, thanks a lot, and I’m sorry to have caused you so much bother.’ De Valera responded, ‘That’s all right, we’re glad to help you because the flight put Ireland on the map again.’

While he was waiting for officials to decide what to do next, Corrigan visited London, where he met American Ambassador Joseph Kennedy. Corrigan and Sunshine were later sent back to the United States on the liner Manhattan.

Although he could have faced any number of serious charges related to his flight, Corrigan’s great luck, his good nature and his implausible story carried the day. His pilot’s license was suspended until August 4–the day the ship arrived in New York. But that was the only action taken against him.

After all, no matter how many rules he had broken, ‘Wrong-Way’ Corrigan was a hero–and in America he was accorded a hero’s welcome. Corrigan grew reclusive as the years went by, but there were several reports in the late 1980s that he finally admitted to making his famous mistake intentionally. He died on December 9, 1995, at age 88.

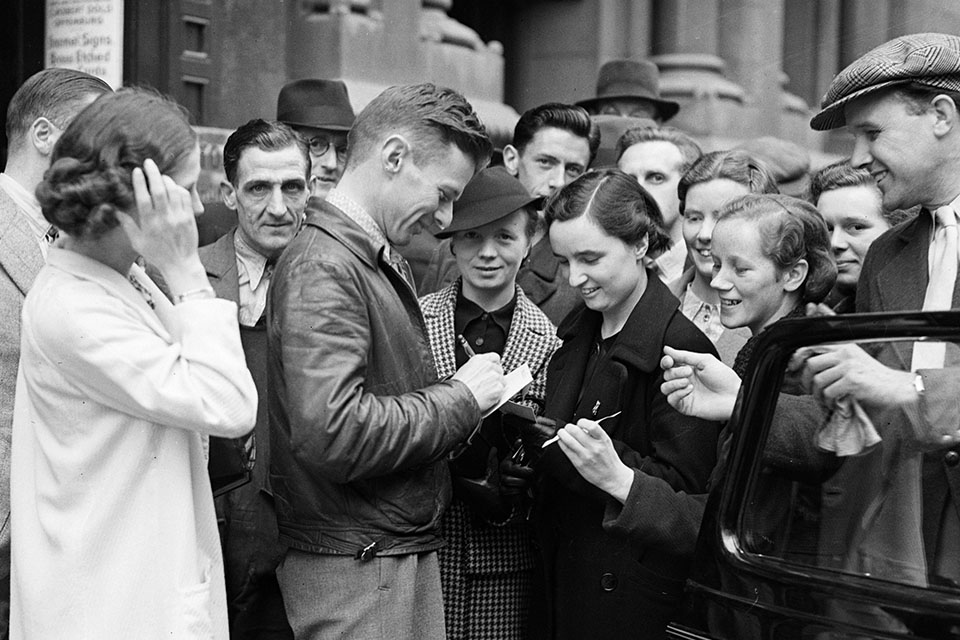

When Douglas Corrigan came back home after his remarkable flight, it seemed as though everyone wanted to celebrate his accomplishment. On the U.S. liner Manhattan, which carried Corrigan and his plane Sunshine from Dublin to New York, the 31-year-old pilot got a taste of what was to come. The ship carried 1,000 passengers and 500 crew members, and during the voyage Corrigan signed 1,500 autographs.

When the ship passed the Statue of Liberty and entered New York Harbor, Corrigan saw a cluster of fireboats shooting up streams of water to celebrate his approach. The next day he was given a ticker-tape parade up Broadway—or, as he called it, a “midsummer snowstorm.” More than a million people lined the streets to see him. There was also a parade in Brooklyn, starting at Floyd Bennett Field, where Corrigan had taken off.

During that event, he was presented with the first of many compasses. Corrigan graciously accepted the gift, but commented, “It wasn’t the fault of my compass that I went the wrong way. I just made a mistake in reading the compass.” There was another celebration at Yankee Stadium that night, and the following night he was given a gala dinner by the Irish Societies of New York.

But New Yorkers were not the only ones who were excited about his daring flight. Many cities wanted a chance to celebrate, so Corrigan made a flying tour of the country. He traveled from city to city in the same modified Curtiss Robin that he had flown across the Atlantic. Along the way, there were parades, parties and receptions from coast to coast. Corrigan met President Franklin D. Roosevelt and had breakfast with the senior members of the Civil Aeronautics Authority and some of the other bureaucrats whom he had defied.

In Tulsa, Okla., Corrigan was initiated into an American Indian tribe as “Chief Wrong-Way.” In El Paso, Texas, he rode in a stagecoach during a parade. He especially enjoyed the festivities in San Diego, where he met up with a lot of old friends with whom he had worked when he was helping to construct Spirit of St. Louis.

In Los Angeles, Corrigan signed a contract to appear in a movie, playing himself. The film, The Flying Irishman, came out later that same year. Corrigan also wrote an autobiography that year, titled That’s My Story. In it, he recorded once more his tale of fog, clouds and a misread compass. And so the traveler came home—in style.

Chris Fasolino writes from Malone, N.Y. For additional reading, try Douglas Corrigan’s autobiography, That’s My Story. To learn more about Ryan Aeronautical and the construction of Lindbergh’s plane, try The Spirit of St. Louis, by Charles A. Lindbergh.

This story originally appeared in the May 2001 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!