June 6, 1944, approximately 4 a.m.: Sergeant John Onken of the U.S. Army’s 4th Cavalry Group peered into the darkness from his landing craft at the indistinct chunk of land barely visible ahead. It was one of the Saint-Marcouf Islands, a few miles off a beach that only a few that morning already knew as Utah. The unremarkable islands once boasted a Napoleonic fortress; no one in Allied leadership quite knew what was there now. Finding out was part of Onken’s mission.

On another American landing craft nearby, Private Anton Elvesaeter also shivered in the chilly sea air, wondering what lay ahead. It’s doubtful the two cavalrymen knew each other, but they had much in common. Neither had been born in the nation whose uniform they wore. Elvesaeter was Norwegian by birth; his native country had fallen to Germany in 1940. Onken had actually been born in Germany—his mother and sisters still lived there under Nazi rule. If neither soldier could claim birth in America, they certainly knew why they were fighting, why Hitler had to be stopped.

Furthermore, John Onken may have felt some additional angst. He was heading to France, where his father had died—as a German soldier in the previous world war.

Both men were ready to do their duty. Their units had been chosen for this special mission late in the planning for the invasion of France, Operation Overlord. Reconnaissance had revealed some German presence on the otherwise uninhabited Saint-Marcouf Islands. If there were Wehrmacht men stationed there, they could conceivably spot the invasion fleet heading to Utah Beach and radio a warning to the mainland, robbing the Allies of the element of surprise. A force was hastily assembled to land in darkness and clear the islands, two hours before the main assault began at dawn.

Tragically, neither Onken nor Elvesaeter would get far into French territory. It turned out that German soldiers were no longer on the islands, but landmines were. It’s impossible to know which man fell first, but both Onken and Elvesaeter died on the beaches of Saint-Marcouf. While airmen and paratroopers had already paid the ultimate sacrifice that morning, the two cavalrymen were almost certainly the first Allied personnel to perish in the sea-borne invasion of Hitler’s Fortress Europe.

Their deaths made a difference, but their stories are little known, their sacrifices virtually forgotten. Yet the names of both men, along with some 4,400 other brothers-in-arms who would die that day, can be found today in a place neither could have ever expected: on somber brass plaques on a curved wall in a small Virginia town.

The National D-Day Memorial is not found in Washington, D.C., or on a military base somewhere. Instead, it is located in Bedford, Virginia, 200 miles southwest of the nation’s capital, because that community had the highest-known per capita loss of American lives on D-Day—20 men from the surrounding rural county died that day.

The Memorial features panoramic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains, evocative sculpture, and a soaring arch commemorating the events of June 6, 1944. But it has another important distinction: at the Memorial, preserved on hundreds of plaques and an ever-evolving computer database, is the most comprehensive roster of the D-Day fallen anywhere in the world.

The effort to give names to all of the D-Day dead began in 2000, before the Bedford site had even opened. The board of the Memorial’s governing foundation had adopted a laudable but challenging ambition: to identify every Allied soldier, sailor, airman, and coastguardsman who died on D-Day. Such a list of the dead from a single event is termed a “necrology”; hence the research endeavor became known at the Memorial as the Necrology Project.

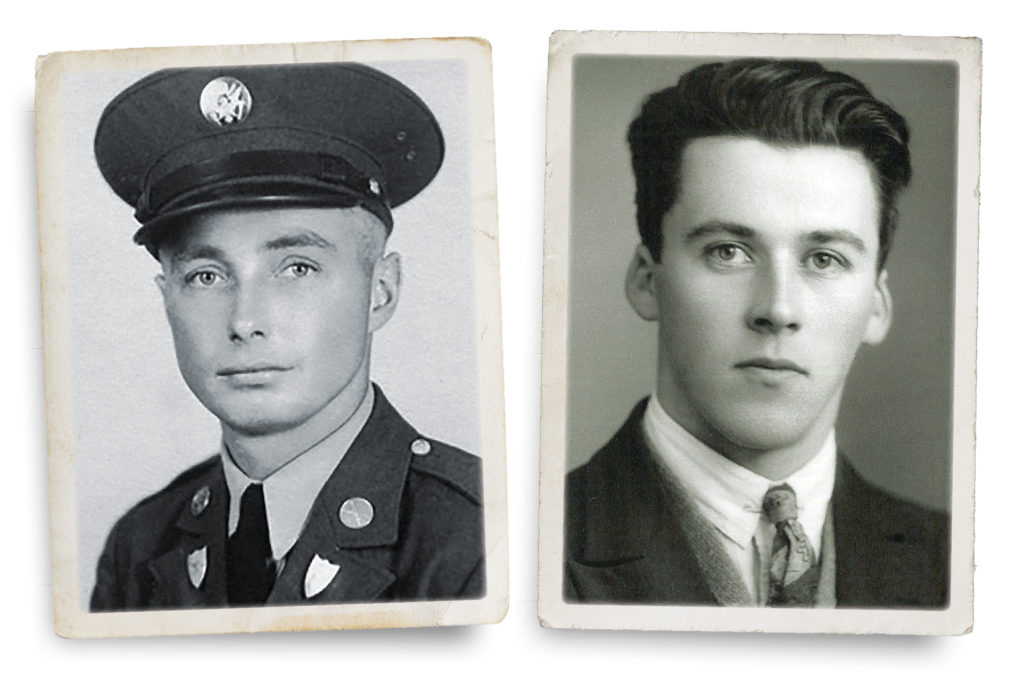

American cavalrymen Sergeant John Onken (left) and Private Anton Elvesaeter (right) were the first Allied soldiers to die in the seaborne phase of Operation Overlord. Both men were killed by German landmines on the uninhabited Saint-Marcouf Islands a few miles off the Normandy coast. (Courtesy of the National D-Day Memorial Foundation)

It asked what seemingly was a simple question—surely there was a roster somewhere? But finding an incontrovertible answer proved perplexing. Heading up the project in its infancy was the redoubtable Carol Tuckwiller. A retired librarian from Roanoke, Virginia, she had applied for a retirement job with the National D-Day Memorial Foundation, unsure of what exactly would be involved. But recognizing her tenacious research skills, her bosses quickly tasked her with finding the answer to the question of how many died on D-Day.

Surprisingly, as Tuckwiller discovered, no one had thoroughly looked into the question before. Estimates of the D-Day fallen ranged widely but were no more than guesses. Cornelius Ryan’s seminal 1959 history of D-Day, The Longest Day, noted that “over the years a variety of vague and contradictory figures have been given on the losses sustained by Allied troops during the twenty-four-hour period of the assault.” Still, he cited initial reports of fatalities from the U.S. First Army—the American invasion force—as 1,465.

Former president Dwight D. Eisenhower himself mentioned 2,000 casualties in his famous 1964 interview with CBS newsman Walter Cronkite to mark the invasion’s 20th anniversary. Stephen Ambrose’s epic 1994 history, D-Day, cited 4,900 casualties, but with a footnote baldly stating, “No exact figures are possible…for D-Day alone.” It’s worth noting here that the term “casualties” includes wounded, missing, and captured soldiers as well as those killed in action.

So it’s not surprising that from the beginning Tuckwiller discovered that compiling a list of D-Day fatalities was a daunting task. She wasn’t even entirely sure where to begin to look for the information. She started with what seemed to be a logical person: a deputy director of mortuary affairs at nearby Fort Lee in Virginia. As she would later tell the story:

After explaining to him that I was researching the names of all members of the Allied Expeditionary Force [the Allies’ multinational military in northwest Europe] who lost their lives on D-Day, June 6, 1944, his initial response was “You can’t do that!”

“Why not?” I asked, thinking there must be a security problem with accessing the records.

“Because it’s never been done before!” he continued.

“I know it hasn’t; that’s why I’m doing it,” I replied.

“No, you don’t understand,” he said. “There is no single place where you can find a list of names of people who died on a particular day.”

Indeed, Tuckwiller would soon discover that there was no single place to look. The Normandy American Cemetery—the iconic cemetery above Omaha Beach so vividly portrayed in Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film, Saving Private Ryan—was a natural place to begin her re-search and, in fact, burial lists and grave markers there yielded some of the first names. But not all D-Day fatalities lie there, so other sources had to be scoured. With Dr. William McIntosh, the Memorial Foundation’s education director and later president, championing and advising her effort, Tuckwiller painstakingly hunted down unit after-action reports, ship logs, headstone applications, hometown obituaries, Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs), and other primary sources. Morning Reports—daily accountings of men killed, wounded, or missing at the company level—were especially fruitful.

Along the way Tuckwiller realized that according to military protocol of the day, missing men were not officially declared dead until a year and a day after their disappearances. So June 7, 1945, became another date she had to pursue. U.S. Army (and Army Air Forces) records were her primary sources, but the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard lost men that day as well in the English Channel and on the Normandy beaches.

Boundaries had to be set for inclusion on Tuckwiller’s list, and the most important was a 24-hour one. Although the scenario was certainly common, men wounded on D-Day but dying later were not put on the roster. For airmen, MACRs were essential, although it wasn’t always initially known if a man or crew shot down had survived or been captured. So POW records also had to be compared.

Also highly informative—if often heart-rending—were IDPFs: Individual Deceased Personnel Files. In contrast to service records (so many of which were lost in the catastrophic 1973 fire at the National Archives repository in St. Louis), IDPFs deal exclusively with the disposition of a serviceman’s remains after his death. In addition to describing a man’s initial burial on the battlefield, the means by which his remains had been identified, and of course the all-important date of his death, IDPFs often included correspondence with the serviceman’s family as they sought confirmation of his identity or further information.

Such correspondence often reveals the tragedy endured by family at home. Private First Class Thomas Saccone, 21, of New York City fell on D-Day serving with the 82nd Airborne Division—by one account the paratrooper drowned after landing in a flood zone. But for most of the following year, his mother, Angela, refused to believe it, hoping against hope that her son was alive somewhere. “I have no definite proof that my son was killed…. I wasn’t told if his body was found, if he was buried properly, and I also have not gotten any of his personal belongings,” Mrs. Saccone wrote in letters to various officials for months after he fell. “I haven’t received anything giv-ing me definite proof.… In fact, I as a mother do not believe my son is dead.” Patiently but firmly, military officials responded to her queries with somber assurance: no mistake had been made. Thomas was dead.

Over time Mrs. Saccone came to accept her loss, but her example is a telling one. Thomas Saccone likely suffered only briefly. His mother’s anguish was much more prolonged. It’s a reminder that for every name on the Memorial’s Necrology Wall, there was also deep pain for the family left behind.

Endless complications materialized during Tuckwiller’s research. Men had the same or similar names, spellings varied in records, copies of documents were smudged or otherwise inscrutable. Then there were the dates. Tuckwiller’s whole project hinged on what happened—or could be confirmed as having happened—on a single day. But a lack of precision in recording death dates proved endlessly frustrating. Often definite dates could not be known—if a trooper’s remains were discovered days or even weeks later, who was to say on what day he gave his life? Other times dates seemed to have been almost arbitrarily assigned. The Naval Beach Battalion records list a surprising number of men killed not on June 6 but on June 8. How many of those men actually died on D-Day?

To be fair, the U.S. military was as scrupulous in record-keeping as the chaos of war would allow. Graves Registration companies—those tasked with locating, identifying, and burying the dead—went about their macabre tasks with impressive diligence. On the home front, military officials were determined to notify next of kin of a fallen serviceman as quickly and accurately as possible, although in this pre-internet era more than a month usually passed between a man’s death in battle and his loved ones receiving the telegram every American dreaded.

Amid these laudable priorities, determining an indisputable death date took lower precedence. Yet decades later Tuckwiller and her small team—other museum staff who lent support, as well as a faithful volunteer—were looking exactly for that, an indisputable death date of June 6, 1944. Thousands of names were found. But many others who almost certainly, but not provably, died on D-Day had to be excluded.

Location was another complication. Just because a man’s death date was June 6, 1944, it didn’t mean he died in the Normandy invasion. Men died on that date on many other battlefields. The name Edwin Boehme, a New York airman, was listed on the Necrology roster for many years, until it was determined that while he died on June 6, 1944, his plane was lost over the Adriatic after a raid on the German oil fields at Ploesti, Romania. His name was removed from the roster of D-Day fallen but honored with an inscribed brick in the Memorial’s Gold Star Garden.

As if combing through the morass of American records wasn’t challenging enough, Tuckwiller didn’t stop with the Yanks. The goal was to identify every Allied D-Day fatality. Men from Britain, Canada, France, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, and Belgium also fell in battle on that momentous day. (Poland, Greece, Czechoslovakia, and Holland, all occupied nations, supplied men for Overlord but suffered no known fatalities.)

Tuckwiller turned to military attachés and the various embassies to supply rosters. Britain and Canada suffered many hundreds of fatalities; the others fewer. Norway proudly offered a list of several dozen sailors killed aboard the HNoMS Svenner, a British destroyer turned over to the Norwegian navy-in-exile that was sunk by a German torpedo boat off Sword Beach, as well as a few airmen killed alongside the British RAF. Norway was a nation occupied by Nazi Germany. These men knew exactly why they were asked to fight.

Ironically, few French soldiers were lost liberating their nation on D-Day; most of the dead were part of a small commando unit attached to a British division. But the French embassy also requested that names of some personnel with the French Forces of the Interior—the organized resistance—be included among the battlefield dead. Some who had been imprisoned were executed by their German captors that morning when it became clear that the invasion had begun. Sadly, these heroes may well have died without knowing that the liberation of France was underway.

Despite the complications, contradictions, and gaping holes in the records, Tuckwiller persevered. After one year, she had confirmed some 400 names. And by her 2006 retirement, after six years on the job, the roster had increased almost elevenfold: in total, she had identified 4,390 Allied names. Since then, other Memorial staff have picked up where she left off and continue the work.

The roster of American D-Day heroes is an interesting study in demographics. Men from every state in the union in 1944, plus Washington, D.C., gave their lives on D-Day. Their names represent the American melting pot: Italian, Polish, Hispanic, Czech, Russian, Jewish, and Irish surnames all appear. There is one general—Don Pratt—and two Medal of Honor recipients (1st Lieutenant Jimmie Monteith and Technician 5th Grade John J. Pinder Jr., both of the 1st Infantry Division’s 16th Infantry Regiment). Digging through the records one will find a private named Captain, a lieutenant named Sargent, a tech sergeant named Major, and a navy coxswain named General. Between the United States, Canada, and Great Britain, there are 56 Smiths.

The Necrology Project of the National D-Day Memorial is not, and likely never will be, considered a finished assignment. (And new information about D-Day will continue to be revealed. See this issue’s “Need to Know” on page 26.) Names are periodically added. On Memorial Day 2021 paratrooper Captain Clarence Tolle and Ensign Frederick Nye Moses, U.S. Navy Reserve, were honored and eulogized as their names were added to plaque W-33 at the Memorial. Initially, the death dates of both men had been confused in the record, but research uncovered new evidence—including eyewitness accounts—that pointed incontrovertibly to their loss on June 6.

The names of American dead, incidentally, are found on the west side of the wall; Allies on the east. No other distinction is made. All of the names appear randomly, not alphabetically—just as death was random on D-Day.

Even now, the Memorial staff is researching more than a dozen names for possible future inclusion. While contradictions in death dates are still difficult to reconcile, the internet today provides sources Tuckwiller and the initial researchers could only have imagined. Detailed records, such as headstone applications or Missing Air Crew Reports—that Tuckwiller once had to travel cross-country to explore—now are available with a few mouse clicks.

To date, there are 4,415 names on the Memorial’s Necrology Wall: 2,502 Americans and 1,913 Allies. If we could have perfect knowledge, there would be more. But even so, for visitors, the sheer quantity of names inspires awe and reflection as the true cost of D-Day is revealed in tangible human form. Part of the Memorial’s mission is to publicize the results of this project so that every man who fell is counted and honored.

These 4,415 men didn’t want their names at a memorial, but they did their part in one of the most consequential days of the war all the same. They were no more heroic than men who fell on June 5 or 7; nor were they greater heroes than those who died at Okinawa or Inchon or Da Nang or Fallujah. But they were heroes nonetheless; their lives and their deaths mattered. So their names must be remembered.

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2022 issue of World War II.