Some of these mutts flew just fine. Others barely made it into the air. But aviation would be the poorer if it didn’t have engineers willing to take such risks.

One of aviation’s oldest clichés is that if an airplane looks right, it’ll fly right. Whether our selection of aviating dogs affirms or contradicts that aphorism is debatable. Some of these mutts flew just fine and were oddly configured simply so they could fulfill their mission, whether it was sub-hunting or crop-spraying. Others barely made it into the air and were a danger to their pilots and anybody below them. But aviation would be the poorer if it didn’t have aeronautical engineers willing to take such risks. Some of them might have become minor-league Burt Rutans—few would claim that Rutan’s designs are classically beautiful—and others went back to the drawing board to try again.

Here, then, are our nominations for the 13 ugliest airplanes ever to fly. And yes, we know we overlooked the Caproni Stipa Flying Barrel, Short Seamew, Airspeed Ferry, Armstrong Whitworth Ape and PZL M-15 jet biplane, among many others, but feel free to write us to nominate your favorite also-rans.

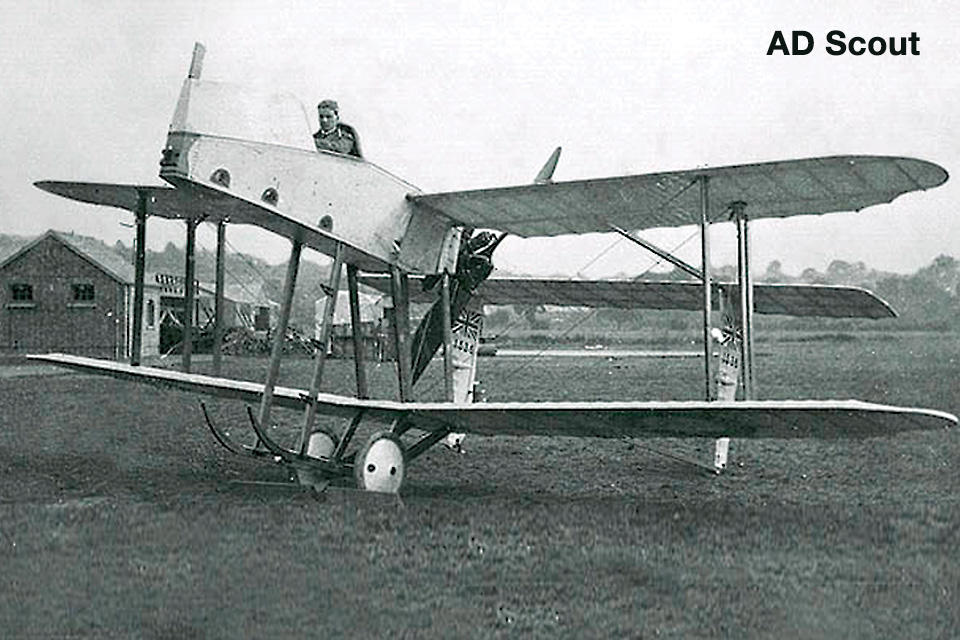

It’s easy to mock World War I designs, since the war erupted only a decade after the Wrights first flew, and their Flyer was no beauty queen. Engineers had yet to figure out exactly what an airplane should look like. Rumpler Taubes, F.E.2s and Vickers Gunbuses shared the sky with relatively conventional SPADs and Fokkers. But the AD Scout, an anti-Zeppelin defender designed by the Royal Navy’s Air Department (hence AD), must have occasioned puzzlement even then. Basically an upside-down biplane, it featured a high-mounted pilot-and-gun pod that ensured the airplane was unstable in flight and handled like an overloaded supermarket cart on the ground. Four were built—two, appropriately, by Blackburn, a company that would go on to construct some of the ugliest production airplanes ever to fly. (R.1, Blackburn, Skua, Roc and Beverly, are you listening?)

Originally designed to be steam-powered by Frenchman Alexandre Goupil in 1883, the Duck wasn’t built and flown until Glenn Curtiss found the plans and put together what would today be called a replica, though with a Curtiss OXX engine. Whatever for? Because the ugly duckling had a true three-axis control system. Curtiss was being sued by the Wright brothers, who claimed they had patented the principle of three-axis control, laterally whether by wing-warping (the Wright Flyer system) or ailerons (which Curtiss used). The Duck had aileron-like movable winglets, and Curtiss hoped that by successfully flying it, which a Curtiss test pilot did in 1917, he could prove that the Wright patent was irrelevant. The court didn’t buy that argument, but it didn’t matter. The government that year persuaded Orville Wright to release the patent to all U.S. aircraft manufacturers, so they could get on with building airplanes for World War I.

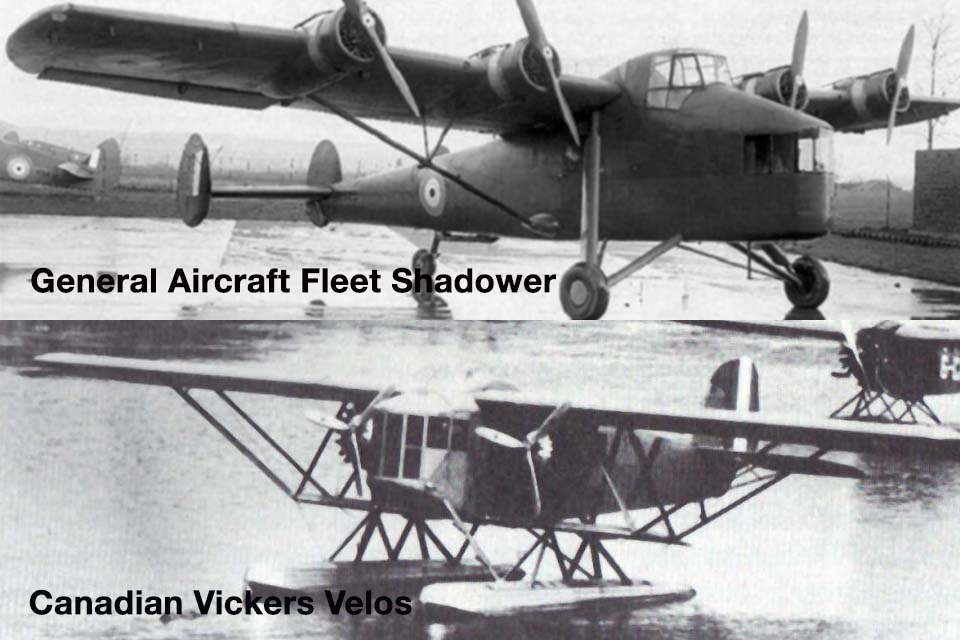

The Velos was at least awarded one accolade: It is generally agreed to have been the worst airplane ever made in Canada. Looking like a winged breakfast nook, or perhaps a flying trolley car, the Velos was designed to be a photo-survey airplane, assumedly with the shooter standing in the glassed-in front porch and snapping away with a big Speed Graphic on a tripod. The Velos was essentially designed by Canada’s Department of National Defence, reminding one of the maxim “a camel is a horse designed by a committee.” The only example ever built flew so badly that Vickers company pilots referred to it as the “Deadloss.” Despite its test pilot’s report that the Velos was “most unsuitable for any operations carried out by the Royal Canadian Air Force,” it spent exactly one year flying for the RCAF before sinking at its moorings during a November storm in 1928. Had Canadian Gordon Lightfoot been alive, he might have written a song.

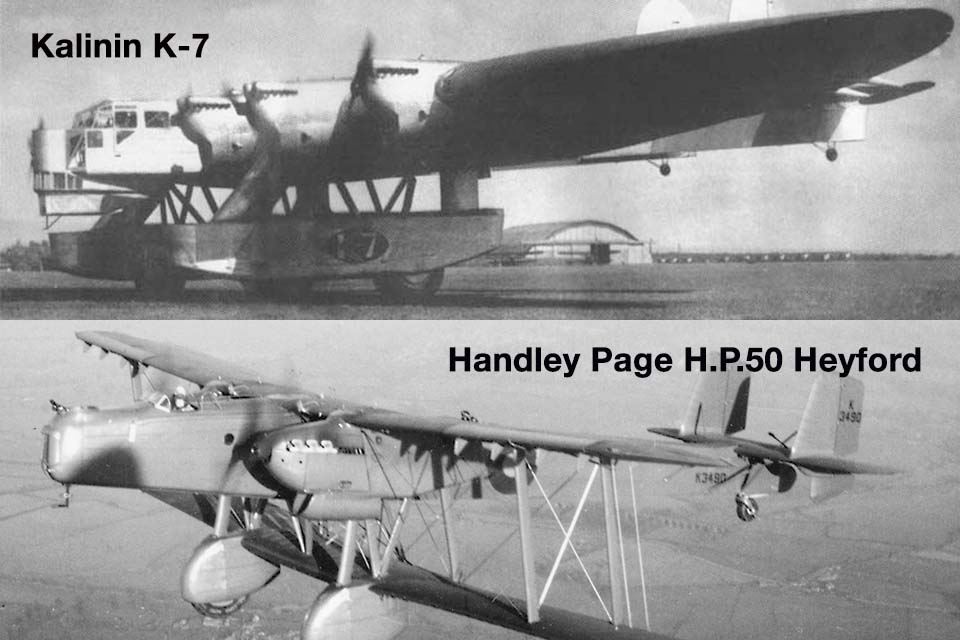

Talk about a flying anachronism: This largely fabric-skinned, open-cockpit, fixed-gear biplane “express bomber” with a World War I open-pit nose-gun emplacement was designed and flown just a couple of years before the U.S. Army Air Corps’ all-metal, retractable landing gear Martin B-10 monoplane was aloft. The B-10 cruised at 193 mph, while the Heyford dawdled along at barely 120. Though it never dropped a bomb or fired a gun in action, the Heyford was the RAF’s most important heavy bomber during most of the 1930s, and one was said to still be in service as late as 1944. Pilots apparently liked the Heyford, though sitting far higher than anything else they’d experienced (nearly 17 feet up) meant it took lots of practice to learn to land one. Trivia: An experimental Heyford was the first airplane to carry radar.

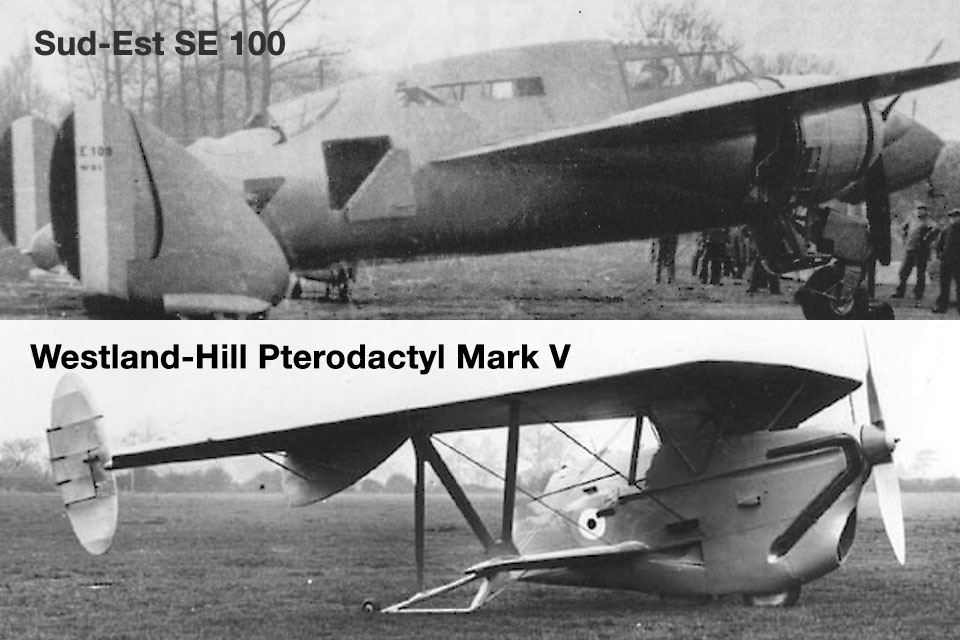

Until accurate airspeed indicators, stall warners, benign wing designs and vastly improved pilot training came along, the aerodynamic stall followed almost inevitably by a fatal spin was aviation’s bugbear. Beginning with the 1924 Pterodactyl Mk. I glider and progressing to this 600-hp fighter prototype, British aeronautical engineer Geoffrey Hill developed a series of tailless flying wings that resisted stalling. Even when they did stall, the Pterodactyls remained controllable…right until they hit the ground, since a high sink rate was often a characteristic of such “unstallable” designs. The Mk. V, powered by a Rolls-Royce V-12, was slightly faster (190 mph) than biplane fighters of the era, but had no offensive capability: The gunner, sitting in the tub behind the pilot, could only fire at attacking airplanes, which nobody seemed to have considered as they boasted of the “unimpeded field of fire.”

The Soviets might not have built particularly advanced airplanes, but they sure built big ones. Igor Sikorsky’s Ilya Muromets series of transports and bombers is the best known, with classic photos showing crew members strolling atop a fuselage in flight like Nelson on the quarterdeck of HMS Victory. But Konstantin Kalinin’s seven-engine monster (six pulling, one pushing) attained new heights of flying-locomotive excess, enough that Internet images of a Photoshopped 12-engine K-7 bearing battleship gun turrets fooled many. Early test flights revealed that the airplane’s floppy tail structure resonated badly in response to propwash from that seventh engine—a late addition so the K-7 could get airborne. During one thankfully short test hop, the elevator oscillated through an amplitude of 3 feet. Hard to imagine who the Soviets intended to bomb with K-7s, but perhaps an airplane with a wingspan bigger than a B-52’s would simply have frightened their targets into submission.

Complex multi-gun, bomber-killing twins like the Bell Airacuda and the Messerschmitt Me-110 were all the rage in the late 1930s, and the SE 100 was the French journey down this dead-end street. The ultimate SE 100 (never built, since the Germans arrived in Paris before the Citroën factory just outside the city could tool up for production) was to have six fixed 20mm cannons in the nose, a twin 20mm flexible mount aft and a seventh swiveling cannon in the belly, giving it substantially more firepower than a P-38 or P-47 would have four years later. The SE 100 also had retractable tricycle landing gear, in those days a nearly unheard-of innovation. Maybe because tri-gear was so unheard-of, the French got it backward: one wheel on the nose, two at the tail. But think of all the money they saved on hydraulic struts and brakes, since the big nosewheel did all the steering and braking, and the little tailwheels were just along for the ride. Incroyable!

It’s a stretch, but you could call this the world’s first stealth plane. It was designed to cruise noiselessly and thus undetected at night, flying not much faster than a fast ship in the bargain, above Kriegsmarine battle groups trying to break out of Germany’s Baltic harbors. It had four little Pobjoy radial engines that could be throttled back to snowblower decibels while their propwash blew over full-span flaps that allowed the airplane to fly just above its 39-mph stall speed. The result of that mission requirement was something that looked like the papier-mâché phony airplanes that were parked in fields to fool enemy photorecon into thinking they constituted squadrons of novel four-engine bombers. Only one GA Fleet Shadower was built.

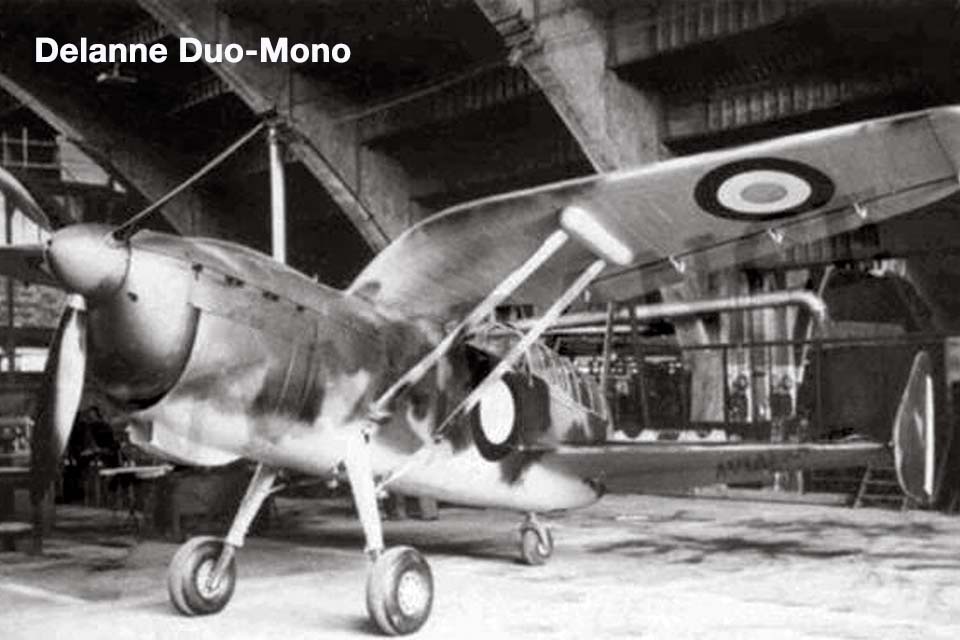

A grim joke about aircraft accidents is that the pilot is always first to the scene of the crash. If a Duo-Mono went in, however, the crew would arrive late, since both men sat in the tail. Because of superficial similarities, some aviation historians have confused the Delanne tandem-wing designs with Pierre Mignet’s Flying Flea concept, but that is—forgive the pun—a canard. The control systems and overall concepts were different, and Maurice Delanne put his “second wing” at the tail not only to exploit helpful aerodynamic interactions between the two wings but to provide a center-of-gravity range broad enough to permit a comparatively small single-engine airplane to carry a big tail gun. (The British Westland Lysander P.12 was an equally ugly Delanne-type design that had a four-gun tail turret big enough for an Avro Lancaster.) The concept of a fighter with a maneuvering pilot and a separate gunner often working at cross-purposes was fatally flawed, however, so Delanne’s design was consigned to the dustbin of aviation history. Whew.

The football-shaped Goblin was designed to be carried in the bomb bay of a B-36 and launched to fight off attacking MiG-15s, then return to the mother ship’s hook-and-dock trapeze after assumedly winning the air battle. Which was about as smart as taking a go-kart to the LeMans 24-hour race because it was small enough to fit inside your station wagon, since it’s doubtful the Goblin could have held its own against a well-flown P-51. Inevitable space constraints meant the Goblin’s fuselage was barely longer than its J34 turbojet engine, and its swept wings had to fold for in-transit storage. The carrier airplane’s turbulent slipstream also made it nearly impossible to fly the XF-85 back onto the underbelly hook that would retrieve it after battle, assuming there was anything to retrieve. (Never tested with a B-36, the only actual XF-85 launches and retrievals were made from a B-29.) The final indignity was that the airplane was termed a “parasite fighter,” making it sound like medication to sprinkle into your undies rather than a weapons system.

The Deux-Ponts (French for “double-decker”) was known to a generation of British schoolboys as the Duck’s Pants and was about as attractive as that garment might sound. If the Lockheed Constellation was a dolphin, the Deux-Ponts was a manatee. Yet it was an excellent airplane, flying for Air France, the French Armée de l’Air and a few smaller operators from 1952 through 1971. With two full passenger decks, it could seat 135 in a pinch, substantially more than its only double-deck competition, the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser—which in fact had only a partial lower deck configured as a cocktail lounge. But the Deux-Ponts was unpressurized and had a capacity far beyond what any airline of the time needed. It was also powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-2800 radials in an era when turboprops and even pure jets were becoming the norm. The enormous Airbus A380 is therefore Air France’s second ugly double-decker.

As goofy-looking at it is, the PL-11 Airtruck was in fact a successful crop-duster, appreciated by the pilots who flew it for a living. Only two were built, in New Zealand, but some of the 118 examples of its successor, the Australian Transavia PL-12 Airtruk, are still at work all over the world. The Airtruck and Airtruk were designed for a specific job—aerial application—rather than adapting a conventional airplane to the task. The pilot was placed high above both the engine and the chemicals hopper, rather than sitting between them waiting to be crushed in a crash, and the perch gave him a superb view for low-level maneuvering. The aft fuselage, often severely corroded by spilled chemicals in conventional dusters, was simply eliminated, replaced by two empennages at the ends of simple booms. (That the booms were intended to allow easy loading from a truck backed up between them is an oft-stated myth, since loading a conventional crop-duster’s hopper from the side is equally easy.) The Airtruck’s radial engine was a complete North American T-6 firewall-forward unit, nacelle and all; Bennett had bought a bunch of surplus, wingless RNZAF Harvards for £5 each.

If there’s a jet that makes the rock-candy Lockheed F-117 look attractive, this is it. Looking like the space shuttle swallowing an F-15, the X-32 was Boeing’s unfortunate entry in the program to develop a Joint Strike Fighter suitable for the U.S. Air Force, Navy, Marines, RAF and Royal Navy. Since the Department of Defense has yet to learn that a one-size-fits-all fighter is dumb, we’re fortunate they didn’t also demand regional-airliner capability. The B model of the X-32 could land vertically, since it was intended to replace Harriers. The enormous chin-mounted jet air intake gave the X-32B a bad case of overbite, and the Winnebago-sized fuselage required to hold all the STOVL (short takeoff/vertical landing) ductwork hit it with an ugly stick. Why an X-32A and an X-32B? Because neither version alone could carry all the equipment required to fly both as fast as F-16s and in STOVL mode.

Frequent contributor Stephan Wilkinson nominates the Caproni Stipa (covered in detail in the “Extremes” column by Robert Guttman in Aviation History’s March 2010 issue) for the ugliest airplane grand prize. Many more worthy candidates can be found on the Internet simply by searching “ugly airplanes.”

This feature originally appeared in the May 2011 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!