The New York Times called him “the Evil Genius of the Republican Party.” The Confederate army that invaded Pennsylvania in 1863 dispatched cavalry to burn down his iron foundry, just to spite him. The president of the United States suggested that he should be hanged. After he died, in 1868, his party decided to honor him by nominating him for reelection to Congress. He won in a landslide.

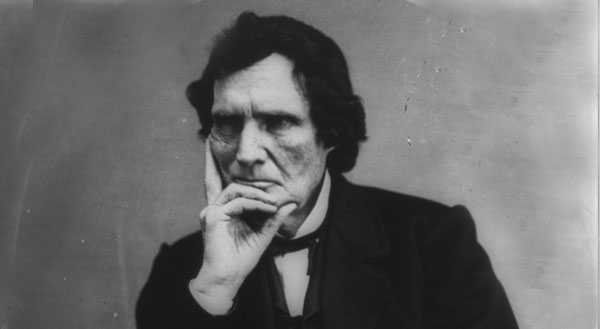

His name was Thaddeus Stevens and for a time he was the most powerful man in Congress, famous across America as “The Old Commoner,” loved by many, loathed by many more. But over the last century his once famous name faded into the mists of history, until Tommy Lee Jones brought his spirit back to life in Steven Spielberg’s hit movie Lincoln. Jones plays Stevens as a snide, cynical, misanthropic old pol with a bad wig and a black mistress. In one scene, Stevens, speaking on the floor of the House of Representatives, lambastes a proslavery congressman, calling him “proof that some men are inferior, endowed by their creator with dim wits, impermeable to reason, with cold, pallid slime in their veins.”

All of that is pretty accurate, as movies go. Stevens really was a nasty man who used his slashing wit as a weapon. When an opponent interrupted one of his House speeches with a request to speak, Stevens replied, “I yield to the gentleman for a few feeble remarks.” During another House speech, Stevens ripped into a proslavery congressman: “There are some reptiles so flat that the common foot of man cannot crush them.” But the crusty Old Commoner’s anger and cynicism masked a bone-deep idealism that the movie only hints at. Stevens fought harder to win freedom and equality for black Americans than any politician in our history, including Abraham Lincoln. And his most hard-fought battles occurred after Lincoln’s death.

“I do not believe, sir, in human perfection,” Stevens said in a speech, “nor in the moral purity of human nature.”

He learned about human imperfections early: He was born in Vermont in 1792 with one leg crippled by a clubfoot. That deformity wasn’t the only blight on his childhood. His father was a drunk who deserted the family, leaving them destitute. His mother supported her children working as a maid, and she managed to eke out enough money to send Thaddeus to Dartmouth. There, he began to exhibit a lifelong scorn for those lucky souls born healthy and wealthy.

After graduating in 1814, Stevens moved to Pennsylvania to teach school and study law. He passed the bar, opened a law office in Gettysburg and quickly became one of the state’s most successful attorneys, frequently appearing before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

In 1821, he was hired by a Maryland slaveowner who wanted to regain possession of a runaway slave who was living with her two children in the free state of Pennsylvania. The slave, Charity Butler, claimed she’d resided in Pennsylvania for more than six months—long enough to be declared free under state law. But Stevens proved that Butler hadn’t lived in the state for six consecutive months, and he won the case. Later, when he pondered how his courtroom cleverness caused three human beings to lose their freedom, he was appalled, and he became a dedicated abolitionist.

Running on the Anti-Masonic Party ticket, he won election to the state legislature in 1833, part of a populist movement against Freemasons, who were widely perceived as a secret elitist cabal. He sponsored a bill to curb secret societies, but his lasting influence came on a more important issue—public education. In 1834, Stevens helped pass the state’s first law to fund free public schools. Many affluent Pennsylvanians were outraged: Why should I pay taxes to educate somebody else’s children? In 1835, a bill to repeal the controversial education law was headed for victory when Stevens rose to address his colleagues. Speaking passionately of his childhood, he testified that education had lifted him from poverty, and he begged the legislators to give future generations a similar chance to rise.

“Build not your monuments of brass or marble,” he urged. “Make them of everlasting mind!”

As he limped back to his seat, his fellow legislators applauded. Then they voted to continue Pennsylvania’s free schools. Decades later, Stevens recalled that moment as his greatest triumph.

In 1842, Stevens moved from Gettysburg to the larger town of Lancaster. At 50, he was a wealthy attorney, owner of an iron foundry and many other properties. Unmarried, he hired Lydia Smith, a 33-year-old mulatto widow, as his housekeeper. An attractive, intelligent woman, she lived with Stevens for the rest of his life, fueling rumors that she was his lover. “Thaddeus Stevens has for years lived in open adultery with a mulatto woman,” a Southern newspaper declared. “This mulatto manages his visitors at will, speaks of Mr. Stevens and herself as ‘we,’ and in all other things comports herself as if she enjoyed the rights of a lawful wife.”

The rumors were probably true. Stevens certainly treated Smith more like an equal than an employee. He even hired a prominent artist to paint her portrait. She was at his bedside when he died and he left her $5,000 in his will—enough for her to buy the house they’d shared in Lancaster. In 2003, historic preservationists working on that house discovered evidence that Stevens and Smith used it as a station on the Underground Railroad, concealing runaway slaves in a hidden cistern connected to the house by a secret tunnel.

In 1848, Stevens was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and became a leader of congressional abolitionists, fighting against the Fugitive Slave Law and the spread of slavery to western territories. He delighted in verbal sparring with proslavery congressmen. When a Louisiana senator proclaimed that slaves were “the gayest, happiest, the most contented, and the best-fed people in the world,” Stevens rose on the House floor with a sarcastic proposal: “If this be so, let us give all a chance to enjoy this blessing. Let the slaves who choose, go free; and the free who choose, become slaves.”

During one particularly contentious House debate on slavery, a Mississippi congressman pulled out a bowie knife and lunged at Stevens. But the man was subdued before he could carve up the Old Commoner.

Speaker of the House Howell Cobb, a proslavery Georgian, watched Stevens and concluded that abolitionism had found its leader. “Our enemy has a general now,” Cobb said. “He is in earnest. He means what he says. He is bold. He cannot be flattered or frightened.”

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Abraham Lincoln insisted that it was a war to restore the Union, not a war to end slavery. Thaddeus Stevens disagreed, urging Lincoln to turn the war into a “radical revolution” that would end slavery and crush the power of the Southern aristocracy: “Free every slave, slay every traitor, burn every rebel mansion if these things be necessary to preserve this temple of freedom.”

In November 1861, Stevens introduced a bill to outlaw slavery in America. It didn’t pass. But he kept chipping away at the peculiar institution, pushing a bill to free slaves in the District of Columbia, a bill to free slaves owned by Confederate soldiers, a bill to enlist 150,000 black soldiers in the Union Army. The District of Columbia bill passed; the others failed. But Stevens—along with abolitionist senators Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson—kept pressuring Lincoln to issue an emancipation proclamation.

“Stevens, Sumner and Wilson simply haunt me with their importunities for a Proclamation of Emancipation,” Lincoln grumbled in 1862. “Wherever I go and whatever way I turn, they are on my tail.”

Lincoln hated slavery, too, but he was waiting for an opportune moment to issue his proclamation. That moment came after the Union victory at Antietam in September 1862. Thrilled, Stevens praised the president and promised his full support.

Stevens’ support was crucial because he was chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee—Congress’ tax-writing body—and Lincoln needed huge sums of money to finance the war. Stevens provided it, pushing legislation that raised or borrowed $4 billion to fund the Union war machine. When antiwar Democrats fought his tax and appropriations bills, Stevens rammed through rules that limited debate—in one case, to half a minute. And the Army got its money.

By the end of 1864, the war was nearly won and the reelected president again turned his attention to slavery. His Emancipation Proclamation was crafted as a wartime measure and Lincoln worried that courts might nullify it during peacetime. He urged Congress to quickly pass the 13th Amendment, which would outlaw slavery forever. The Senate had already passed the amendment, but in the House, Democrats prevented the measure from garnering the necessary two-thirds majority. As the movie Lincoln depicts, the president—assisted by Stevens, Secretary of State William Seward and some shady political operatives—managed to convince, cajole, intimidate or buy off enough Democrats to enact the amendment.

Stevens summed up that story in a sardonic remark that is repeated by Tommy Lee Jones in the movie: “The greatest measure of the 19th century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America.”

Ending slavery wasn’t enough for Thaddeus Stevens. He proposed a plan to revolutionize Southern society: The Union Army would confiscate the plantations of the richest Southern aristocrats and distribute 40 acres of land to each adult male former slave.

“The whole fabric of Southern society must be changed,” he said. “Without this, the government can never be—as it has never been—a true Republic.”

President Andrew Johnson scoffed at Stevens’ radical proposal. Johnson, who took office after Lincoln’s assassination, was a Tennessee slaveowner who remained loyal to the Union when his state seceded. He wanted to reunite the country as quickly as possible. Under his generous rules, Southern states merely had to agree to end slavery and pledge loyalty, and they could send representatives to Congress.

Johnson’s plan outraged Stevens. “Every rebel state will send rebels to Congress,” he predicted. He was right. In December 1865, only eight months after Appomattox, the Southern representatives arrived. Chosen in whites-only elections, they included the Confederate vice president, six members of the Confederate Cabinet, four Confederate generals and 58 former Confederate congressmen. Appalled, Congress refused to seat the Southern delegations.

In the South, the all-white “Johnson governments” passed laws denying black people the right to vote or buy property or own firearms. Some states enacted “black codes” that decreed that blacks convicted of petty crimes could be leased to white employers for months—or years—of unpaid labor.

Ailing and frail, Stevens, 74, rallied the Radical Republicans to defy Johnson and enact laws to protect the newly freed slaves. Congress passed a bill granting citizenship rights to black people. Johnson vetoed it. Congress passed a bill funding a Freedmen’s Bureau to assist former slaves. Johnson vetoed it. Congress passed a bill giving voting rights to black men in the District of Columbia. Johnson vetoed it.

Stevens responded by proposing a 14th Amendment to the Constitution that would grant black men all the rights of citizenship, including the right to vote and hold public office, while revoking those rights from former Confederate leaders and soldiers. Stevens’ proposed changes were too radical even for the Radical Republicans. They drew up a new version of the amendment, which did not mention black voting rights and punished only a handful of Confederate leaders.

Stevens denounced the watered-down 14th Amendment as a “shilly-shally, bungling thing” but voted for it anyway. Why? “Because I live among men and not among angels,” he explained—an eloquent defense of compromise by a man frequently scorned as uncompromising. The amendment passed Congress in June 1866. President Johnson promptly urged Southern states to reject it.

That summer, Johnson broke with the Republicans and toured the country campaigning against them. During a speech in Cleveland, a heckler yelled, “Hang Jeff Davis!” and somebody else responded, “Hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips!” (Phillips was a prominent abolitionist.) Johnson heard that and said, “Why not hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?” Then he denounced Stevens and Phillips as “traitors.”

A few days later, in St. Louis, another heckler yelled, “Hang Jeff Davis!” and the president again responded, “Why don’t you hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?”

Johnson’s rhetoric backfired: Republicans triumphed in the election of 1866, winning veto-proof majorities in the House and Senate. They quickly passed the Reconstruction Acts, which divided the South into five military districts, each controlled by a Union general. In order to return to the Union, the former Confederate states would be required to ratify the 14th Amendment and grant the vote to black men.

Johnson vetoed the Reconstruction Acts but Congress overrode his veto. He fought back by firing hundreds of Republican officials in the South, replacing them with Democrats less interested in protecting the rights of black people. The Republicans responded by passing the Tenure of Office Act, which restricted the president’s power to fire federal officials. Johnson vetoed that bill, too, and Congress once again overrode his veto.

Stevens and his allies were determined to prevent Johnson from firing Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war. Stanton controlled the military, which controlled the South, and he was a Radical Republican. Johnson detested Stanton and demanded his resignation. Stanton refused. Johnson, complying with the Tenure of Office Act, asked the Senate to fire Stanton. The Senate refused. Johnson fired him anyway.

Stanton refused to leave and barricaded himself in his office for several months. Meanwhile, Stevens demanded that the House impeach Johnson for violating the Tenure of Office Act. On February 24, 1868, the House voted to impeach, and dispatched a sick and haggard Stevens to inform the Senate.

Stevens was too weak to walk across the Capitol to the Senate chamber. Aides carried him in an armchair to the door of the Senate and then he shuffled in, leaning on his cane, trailed by other congressmen.

“We appear before you,” Stevens announced in a surprisingly vigorous voice, “and in the name of the House of Representatives and all the people of the United States, do impeach Andrew Johnson…”

Thaddeus Stevens was dying. Some unidentified disease ate away at his body. Gaunt as a skeleton, pale as a shroud, he sat in the Senate with a blanket draped across his lap, dulling his pain with opium and brandy. He was the leader of the House lawyers prosecuting Johnson in the Senate, but he rarely uttered a word. Others were not so quiet. The prosecutors denounced Johnson in gaseous orations full of ornate rhetoric.

The president’s lawyers responded with long legal arguments, asserting that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and that Johnson’s actions did not rise to the level of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” In a classic display of legal hairsplitting, they argued that Johnson could not be convicted of removing Stanton from office because Stanton was still barricaded in his office, refusing to leave.

Week after week, the two sides droned on. Finally, on April 27, Stevens rose to deliver his final summation. Barely able to stand, his voice a weak whisper, he denounced the president as a “wretched man,” a “pettifogging political trickster” and “this offspring of assassination.” Johnson’s crime was serious, he insisted, because it was done to prevent Stanton from protecting the rights of freed slaves. He demanded that Johnson “be tortured on the gibbet of everlasting obloquy.”

He couldn’t finish. He sank into his seat, handing his speech to another congressman to read.

On May 16, 1868, the Senate finally voted. The galleries were packed with spectators who knew the vote would be extremely close. The chief justice of the Supreme Court called the roll.

“Mr. Senator Anthony, how say you?

“Guilty.”

“Mr. Senator Bayard, how say you?”

“Not guilty.”

In the end, it all came down to one man—Edmund Ross, a Republican from Kansas.

“Mr. Senator Ross, how say you?”

“Not guilty.”

Defeated, Stevens was carried from the chamber in his chair. Seething with rage, he glared at the crowd outside with fiery eyes. Somebody asked him what had happened.

“The country,” he growled, “is going to the Devil!”

It was over. He’d lost. But he refused to quit. Obsessed with ousting Johnson, he suggested new impeachment charges and urged the House to investigate whether Johnson supporters had bribed senators to vote not guilty.

Finally, he gave up on impeachment. He advocated a 15th constitutional amendment, which would do what the 14th didn’t: Grant voting rights to black men. But he was too sick to fight for it, too sick even to leave his bedroom, and he knew he wouldn’t live long enough to see it pass.

“My life has been a failure,” he told a visitor to his deathbed. “I see little hope for the Republic.”

Shortly before he died on August 11, he learned that the grave he’d purchased was located in a whites-only cemetery. Incensed, he bought another plot, this one in an obscure graveyard in Lancaster with no racial restrictions. Then he wrote an inscription designed to carve his creed into his headstone:

I repose in this quiet and secluded spot,

Not from any natural preference for solitude

But, finding other Cemeteries limited as to Race

by Charter Rules,

I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death

The Principles which I advocated through a long life:

EQUALITY OF MAN BEFORE HIS CREATOR.

Peter Carlson’s forthcoming book is Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey.