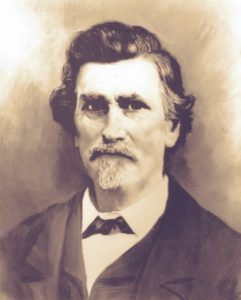

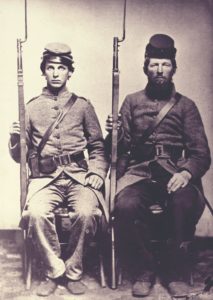

William “Howdy” Martin exemplified the officers who kept rough hewn soldiers ready to fight

On paper, there is little to differentiate William H. Martin from other junior officers in Texas when the Civil War began. In his early 30s, he was a practicing attorney and a former state senator who lived comfortably in the middle-class community of Athens, Texas, with the one notable exception from his peers in that he does not appear to have been a slave owner. Like many of his fellow Texas officers, Martin was not a native-born Texan, but he identified with white Southerners who were sufficiently concerned by the growing power of the Republican Party, its efforts to limit the extension of slavery, and the election of Abraham Lincoln to enthusiastically support secession.

As a leading resident of Athens who organized a company in the spring of 1861, it’s not surprising that the men elected Martin their captain. What is noteworthy, however, is how he earned their respect in the early days of the war when men shifted from enthusiastic volunteers to citizen soldiers bristling at the idea of submitting to military authority. In an effort to speed this transition and prepare the men for war, most of the companies that would later form the Texas Brigade, including Martin’s, drilled in the Texas heat that summer of 1861 and later near Richmond, where officers emphasized drill, order, and a respect for their commanders. This, they argued, was the way to turn raw recruits into disciplined soldiers.

Martin understood the need for training, but he preferred to temper authority with persuasion. When, for example, the men of the “Sandy Point Mounted Rifles” discovered they would have neither mounts nor rifles, it was Martin who convinced them to stay in the ranks while he used his political savvy to secure arms from Governor Edward Clark, reminding him that satisfied soldiers made satisfied voters. Martin also used humor and empathy to temper the subservience required in military life. He earned the nickname “Howdy” for his preference for the Western greeting over a formal salute, and insisted on sharing hardships with his men. “Bill Martin himself is a good officer,” one Houston volunteer observed. “He roughs it all the time, and says that what is good enough for the men is good enough for him.” None of these approaches to effective leadership are revolutionary, but it is noteworthy that of the junior officers in the training camps that summer, few mastered the ability to balance authority with empathy like Martin and it served him well in his command of highly motivated but strongly independent men.

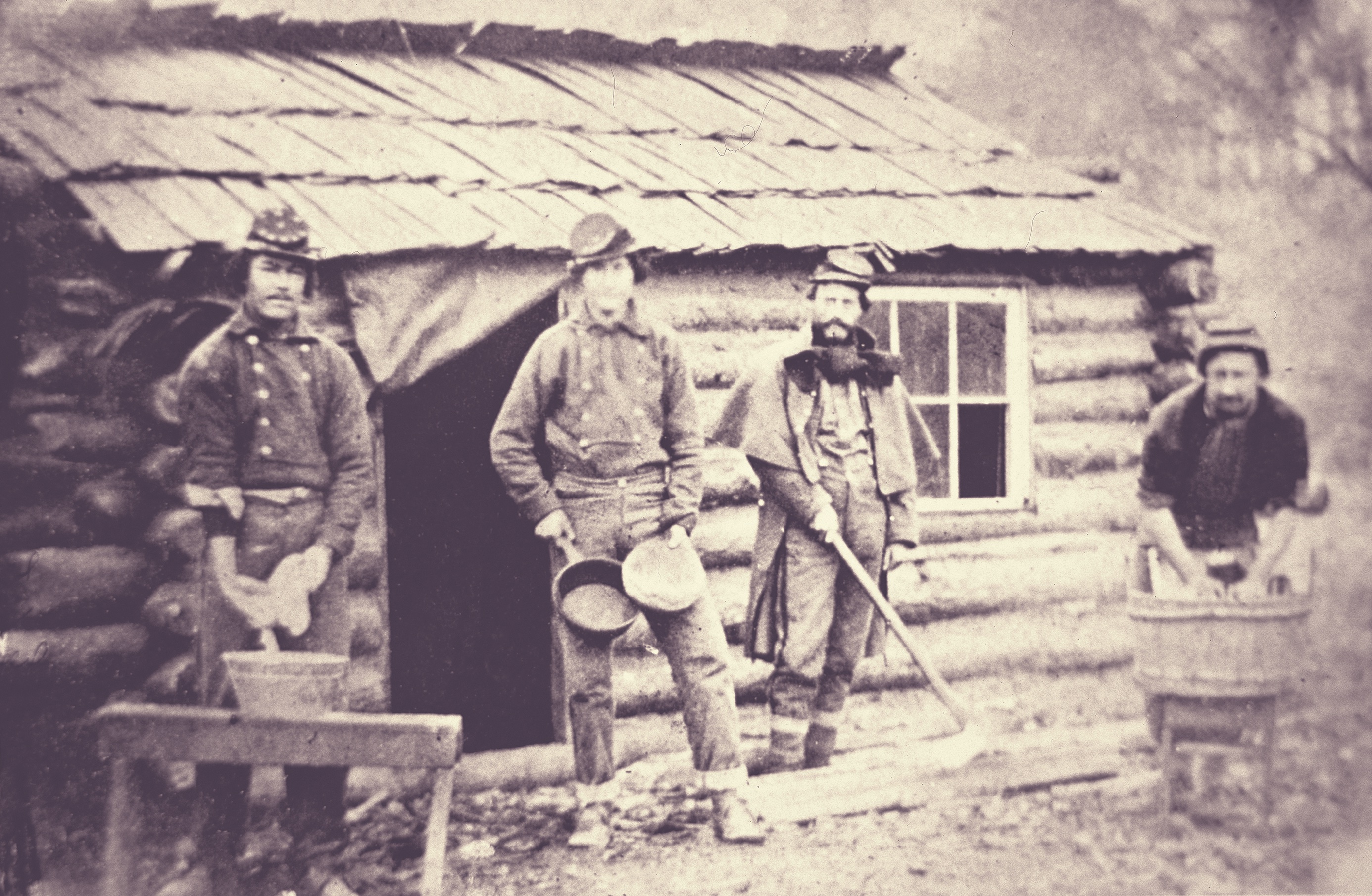

The Texas volunteers who later formed the core three regiments of the Texas Brigade spent that first winter of the war in Virginia. When they weren’t battling the cold, disease, and inexperienced officers, the men earned a reputation for brave, if ill-disciplined, and sometimes unauthorized scouting expeditions into Union lines across the Potomac River. It became clear that it would take unique leaders to turn the Texans into disciplined combat soldiers who could operate as a large unit in cooperation with others. Unfortunately, the selection of those commanders was no simple issue. While the men had been allowed to elect company-grade officers, all of the field officers, they discovered that winter, would be appointed by President Jefferson Davis. This violated the men’s sense of a democratic process and their role, as citizen soldiers, in deciding to whom they would surrender their independence. In response to the perceived injustice the Texans inflicted their outrage on every officer Richmond sent, as well as a few they had elected.

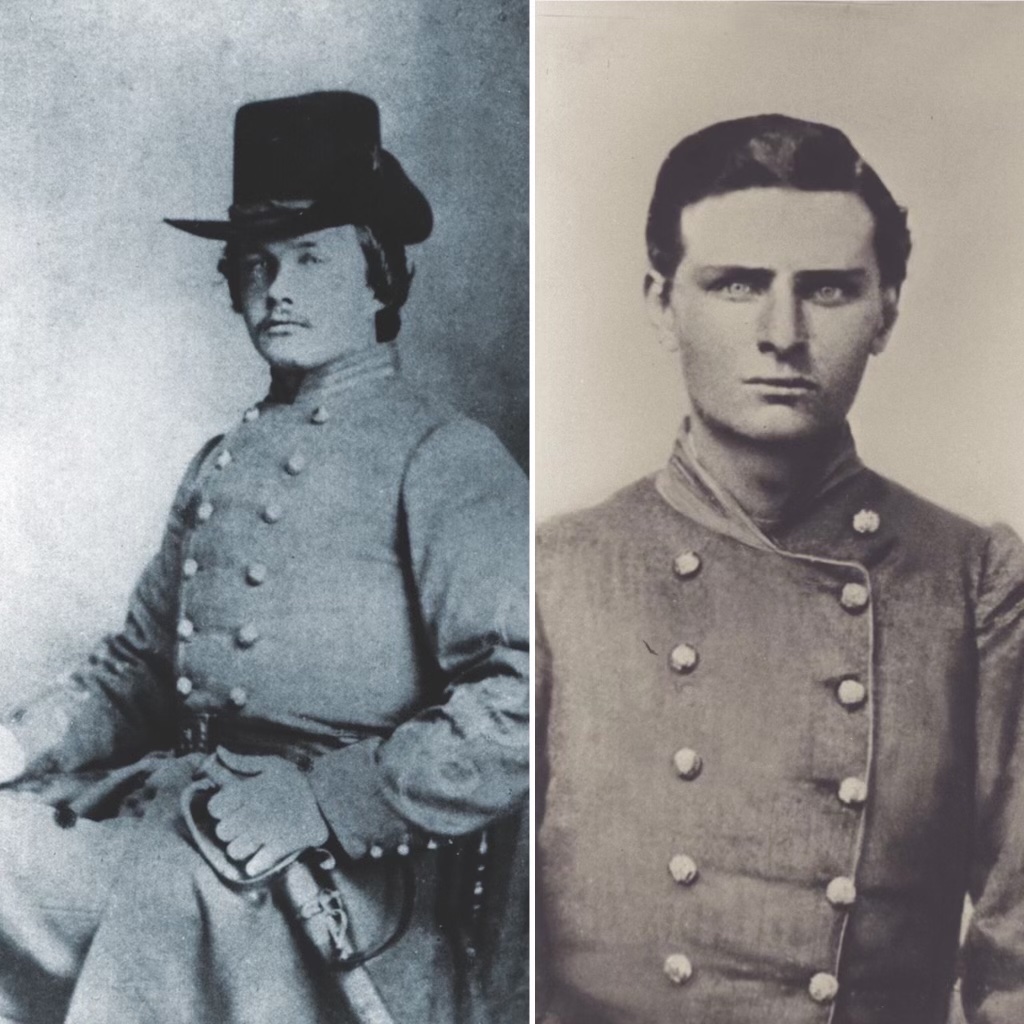

Marylander J.J. Archer, who Davis selected to command the 5th Texas, was deemed “a good, competent, and brave officer,” but the men were not convinced he should lead them. Archer was not, 5th Texan Dugat Williams explained, “a Texan and the whole Regiment has, on this and other accounts, made decided objections to him. They say he is not the man to lead them into battle, that he is from a state too far North and too near Yankeedom for Texas to trust as their commanding officer.” The men believed “that Texans are claimed as the best Soldiers in the Army and they think the position of Colonel is too high for a Marylander to hold over Texans.” Fellow 5th Texan, Tacitus T. Clay, agreed. Archer “may possibly be a very efficient man if in the Command of Regulars, but I fear he is not the right type to control or give satisfaction to Texas volunteers….”

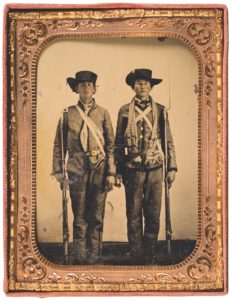

The 5th Texas continued on down the list of appointees from there. They insisted that Major J.J. Quattlebaum was “incompetent and inexperienced” and they played “on his name with verse and song,” tormenting the major throughout camp and in drill. Quattlebaum finally resigned, declaring “that if he had to associate with devils he would wait till he went to hell, where he could select his own company.” The 5th Texans declared their lieutenant colonel, German immigrant Frank Schaller, a dandy and martinet and they finally drove him out of camp on his horse, whose mane and tail they sheared as “sleek as a possum.” Part of the men’s protest was against Schaller as a foreigner, but their primary objection was submitting to a man who did not demonstrate a mutual respect for his men. Schaller did not share the Texans’ rough nature, which rejected overt signs of wealth, urbanity, and formal education. Most officers of the Texas regiments were actually quite wealthy, and the majority of them came from slave-holding families (as did about one-third of the enlisted men). But they preferred commanders who projected a self-made image, rejected Eastern refinement, and who emphasized above all else their respect for the men’s independence.

It’s important to note that Texans could receive equally rough treatment from the volunteers. The 4th Texas rejected Colonel R.T.P. Allen in Richmond despite the fact that he ran a military academy before the war in Bastrop, Texas, and had commanded them during the early training days near San Marcos. He was strong on discipline but rarely showed the respect they demanded. When “Rarin’, Tearin’, Pitchin’” Allen, as they nicknamed him, finally resigned on September 30, several 4th Texans chased behind his horse with switches, driving him out of camp as the 5th Texans had Schaller.

Lieutenant Colonel John Marshall of the 4th Texas fared only slightly better. A respected Austin newspaper editor and personal friend of Jefferson Davis, Marshall was celebrated in Texas that spring for his recruitment of volunteers and his determination that Texans would join the fight in Virginia. But after several weeks in camp outside Richmond, it became clear that Marshall was not a natural commander. “He made a perfect fool of himself,” Thomas Selman explained, “giving wrong orders such as order arms from a present [arms], fix bayonets when they were already fixed. The boys would not obey a single order that was wrong. When the parade was dismissed, every company left the ground whooping & yelling & repeating Marshall’s commands & crying aloud Marshall’s tactics.”

Embarrassed by the event, Marshall studied his manuals and the next day he made just one mistake. But the impression had been made, and men refused to obey his commands. With Marshall, though, they had met their match. Accustomed to his fellow Texans’ attitudes, Marshall refused to leave even when the men submitted a petition demanding his resignation. Similar petitions were levied against other 4th Texas officers, including Company C’s Captain William Townsend and his Lieutenant Decimus et Ultimus Barziza (whose parents were clearly exhausted by the time their “tenth and last” child arrived). Like Marshall, these Texans rejected the protests and continued with their duties. The complaints were almost always the same: too much discipline and submission required of the men and too little respect shown them, but Townsend insisted that “the discontented are the worthless ones—they would be dissatisfied anywhere.” When the campaign season opened, Barziza and Townsend had the opportunity to prove their bravery in battle, which tempered the men’s frustrations and re-established their respect in the ranks. Marshall never had that opportunity; he was mortally wounded early in the brigade’s first major battle at Gaines’ Mill in June 1862.

There is a clear pattern of what the Texans demanded in their leaders, and the accounts from Townsend and others indicate that their protests were not always justified. Dissatisfied volunteers who had never seen combat on the scale they were about to witness were not well positioned to select the best commanders, and these volunteers clearly needed discipline and order. Fortunately for the Texans, they settled on a few exceptional leaders early in the war, including Howdy Martin, who understood, almost instinctively, that leadership involved a power exchange between officers and men. The Texans would sacrifice their cherished freedoms and rights as independent men only to those whom they deemed worthy of that submission. Of all the officers in the Texas regiments in Virginia in the first year of the war, John Bell Hood, Martin’s regimental commander, stood out as the defining example of how to effectively lead this headstrong, highly motivated unit.

Ironically, Hood was appointed, not elected, the commander of the 4th Texas Infantry in September 1861. But from the start, he purposely developed a close relationship with his men. As he explained years later, he used that first winter of the war to seize every “opportunity whenever the officers or men came to my quarters, or whenever I chanced to be in conversation with them, to arouse their pride, to impress upon them that” they would be the best regiment in the brigade; possibly in the army. Hood then used that unit pride to encourage the men to police themselves. If a fellow 4th Texan misbehaved in town, for example, Hood taught his junior officers and the men that “they should, themselves, take him in charge and not allow his misconduct to bring discredit upon the regiment.” In that sense, the men had the opportunity to continue exercising the authority they had in their civilian lives rather than requiring their commanding officer to exercise his power over them.

Similarly, Hood often took the time to explain why orders or certain practices were necessary, and he taught his subordinates to do the same. Men who didn’t obey the lights out orders at the end of the night, Hood explained, hurt their fellow soldiers by making them too exhausted for duty the next morning. Again, Hood encouraged his men to police infractions themselves because those transgressions hurt the effectiveness of the unit, which hurt its reputation and, in turn, hurt the men by diminishing the authority and independence they could still practice in their own lives. It was an incredibly effective approach to an incredibly challenging unit. As Joseph B. Polley of the 4th Texas explained, “Never did I see or know a man to rise higher and more quickly in the estimation of others than did Col. Hood. Well versed in human nature and thoroughly understanding the peculiarities of Texans character,” Hood understood “full well that volunteers would not submit to the same restrictions that would be imposed on regulars.” Hood knew not to “draw the reign of true military discipline very tight at first—issuing few orders and those quite lenient for sometime but gradually increasing.”

The men for the 4th Texas returned that respect in the spring of 1862 when they presented Col. Hood with a horse. Their gift was not “to court your favor,” they explained, but because in Hood they had “found a leader whom we are proud to follow—a commander it is a pleasure to obey. In a word, General, ‘you stand by us and we will stand by you.’” Those were powerful words from men who, that same spring, drove one officer out of camp with switches and petitioned the resignation of three others (who were fellow Texans). By the war’s end, John Bell Hood’s reputation would be in tatters, but he excelled at the regimental, brigade, and even division levels of command. And the Texans never forgot him. Although Hood led their brigade only for about six months in 1862, when they organized as veterans, they named themselves Hood’s Texas Brigade Association.

As a company commander in Hood’s regiment that first winter and spring of the war, Howdy Martin absorbed many of those lessons, though he may not have mastered the art of “gradually increasing” the “reins of military discipline.” The evidence is thin, but several wartime and postwar accounts describe Martin’s role as the standing defense attorney for his men, who often found themselves in the guardhouse for one offense or another. There are also stories of Company K’s camp rarely being the most orderly or his men the best disciplined. This may be why the well-liked Captain Martin, despite service in a hard-fighting unit, wasn’t promoted to major until April 1864. But in battle, Martin and his men were unstoppable and, like the Texas Brigade, they earned a reputation for their steadfast determination and reliability.

Few moments better represent Howdy Martin’s leadership and the Texans’ respect for him than a crisis they faced in the final months of the war. In the early spring of 1865, the Texas Brigade was respected as one of the most elite units in the Confederate Army, but they were facing consolidation. On paper, it made sense. Heavy fighting had reduced the brigade to fewer than 600 men. It would, according to the Consolidation Bill passed by the Confederate Congress, merge with other understrength companies and regiments to return to the size of an effective fighting unit, if with a very different makeup, different officers, and a different unit identification. The Texans had seen this happen to other units such as the Stonewall Brigade, and they refused to accept the idea that after all they had sacrificed for the Confederacy, their celebrated unit would cease to exist.

What was left of the Texas Brigade met that spring of 1865 and elected Martin to make their case directly to President Davis. With the help of connections in Richmond, Martin secured an appointment and set off from camp to present one of the most important arguments of his career. In a classic understated way, he headed into Richmond in “an old blue coat which once belonged to a Union soldier,” with his shirt showing through a tear in the back, and “the Howdy Martin hair” poking through a hole in his hat.

After waiting some time, Martin was ushered in to meet with Davis, and General Robert E. Lee happened to be present as well. Martin insisted that any decision to “consolidate the Texas regiments…would break the hearts of our men….The bones of their comrades are bleaching upon many battlefields in the South” while hundreds of others “returned to their homes broke down in health forever.”

Martin reminded Davis that the men had accepted the full rejection of furloughs home that winter, and that all they were asking to do was continue fighting, but as the Texas Brigade. He even secured a spontaneous endorsement from Lee, who added, “I never ordered that brigade to hold a place, that they did not hold it.” Davis pondered the decision briefly, then nodded and promised Martin that he had won his case. The Texas Brigade remained an independent fighting unit, which it did until surrendering with the rest of Lee’s army several months later at Appomattox Court House.

The leadership that men like Hood and Martin demonstrated in the Texas Brigade balanced the need for discipline and order with a mutual respect the men required. In some ways, this is an exceptional case. The volunteers who comprised the Texas units of the Texas Brigade were some of the most highly motivated men to serve on either side of the war. Despite losing twice as many men in combat as to disease—opposite the statistic for most Civil War soldiers—the brigade had one of the lowest desertion rates in any army, and their families at home, who shared the men’s determination, were able to sustain themselves or each other in the men’s absence.

But the leadership “Howdy” Martin, John Bell Hood, and others demonstrated so successfully in the Texas Brigade speaks to the larger lessons of command in Civil War armies. Volunteers took pride in the title citizen soldier and effective commanders learned to demonstrate their respect for soldiers’ rights as independent men who temporarily chose to obey those deemed worthy of that submission. Few officers understood that power exchange as well as William “Howdy” Martin of Hood’s Texas Brigade.

Susannah J. Ural is professor of history and co-director of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at the University of Southern Mississippi. This article is based on her latest book, Hood’s Texas Brigade: The Soldiers and Families of the Confederacy’s Most Celebrated Unit (LSU Press, 2017).