In 1964 Texas historian and essayist R. Henderson Shuffler stumbled upon a letter by Lieutenant Decimus et Ultimus Barziza chronicling the Confederate 4th Texas Infantry’s performance at Gaines’ Mill, on June 27, 1862. Barziza’s report is one of only a handful of surviving primary accounts from that bloody day. Published anonymously on Va., August 4, 1862, in Richmond’s Daily Whig, it has been cited and excerpted multiple times but rarely, if ever, before presented in its entirety. Shuffler also discovered that a memoir, The Adventures of a Prisoner of War, published anonymously in February 1865, had in fact been written by Barziza.

As his name suggests, Decimus et Ultimus Barziza was the tenth and last child born to Phillip and Cecelia Barziza of Williamsburg, Va., in 1838. Decimus graduated from the College of William & Mary and moved to Texas to study law, then practiced as an attorney.

In 1861 Decimus joined the Robertson County Five-Shooters and was elected first lieutenant of Company C of the 4th Texas Infantry. His first combat came on May 7, 1862, at Eltham’s Landing, Va., near present-day West Point, and he later fought at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, before taking command of Company C.

Wounded in the arm at Second Manassas, Lieutenant “Bar,” as some called him, missed the remainder of the summer and fall campaigns. He returned to duty in time for the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, and despite periodic hospital visits remained with the 4th Texas during the Siege of Suffolk, Va., in the spring of 1863.

Later that year Barziza accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River to Pennsylvania. While leading Company C at Little Round Top on July 2, he was again wounded. Subsequently captured, he was taken to Chester, Pa., then transferred to Johnson’s Island in Sandusky, Ohio. The following February, while being transferred again, this time to Point Lookout, Md., Barziza escaped by jumping from a moving train at night and made his way to Halifax, Nova Scotia. There he happened upon a family friend, Beverly Tucker, who was aiding Confederate POWs.

In late February, Barziza left for Bermuda, then embarked on a harrowing voyage through the Union blockade, landing in Wilmington, N.C. On April 27, 1864, the Memphis Daily Appeal celebrated his return to the South, writing: “Among the arrivals in Richmond, Saturday, we are pleased to note that of Capt. D.U. Barziza of the 4th Texas Infantry.”

A March 25, 1865, note in the Galveston News pointed out that “Captains…P.I. Barziza and D.U. Barziza have been placed on the retired list….They have been disabled, and retired on account of wounds.” After the war ended, Decimus returned to Texas, where he resumed practicing law and then married Patricia Nicholas in March 1869. He died on January 30, 1882, at his home in Houston.

Three years after the following letter was published anonymously in the Daily Whig, the Houston Tri-Weekly reprinted it on April 3, 1865— but incorrectly attributed it to Decimus’ brother Phillip. Not until nearly 100 years had passed was the letter’s real author revealed, thanks to R. Henderson Shuffler.

Dear _____, I have not had, or rather I have not taken the opportunity to write you any of the details of the late battles.

A few days before they commenced, our Division consisting of Gen. Whiting’s Brigade, Gen. Hood’s Texas Brigade, Hampton Legion Infantry and Reilley’s Battery, was ordered to Staunton, for the ostensible purpose of assisting Jackson in the Valley; but in two days we were started straight back, down towards the great army of McClellan. We arrived at Ashland on the evening of the 25th June. The next morning we started early, bearing towards the rear and right flank of the enemy’s lines. About 12 o’clock our advance scouts drove in some cavalry pickets. Moving on, about 4 o’clock, we encountered a small force, who soon fled, and burnt a bridge over a small creek with deep banks, sufficient to retard the movements of artillery.

One company from our Regiment, the 4th Texas, was detailed to construct a bridge, while the Infantry waded the creek and occupied the heights beyond. In less than an hour a good bridge, made of fence-rails, was finished, the road cleared out, and our artillery came thundering over.

All this time we could hear the severe and heavy fighting going on at or near Mechanicsville. The great battle, or rather, the series of great battles, had fairly opened. About dark we formed junction with General Ewell. There was sharp skirmishing in front of us long after dark. We lay in line of battle and slept on our arms, knowing that the next day we ourselves would try the fiery ordeal of battle. Yet we were all cheerful and confident, and no one spoke or even thought of anything but victory. We slept soundly, for we were fatigued: the last sound falling upon our ear being the boom of a distant cannon; but it was the last living sleep many a brave fellow ever enjoyed.

We were on the move early next morning. The fighting was still going on to our right. The enemy had, it seems, evacuated Mechanicsville during the night, and the two Hills [A.P. and D.H.] and Longstreet were pressing upon his retreating columns. We met, during the morning, hundreds of prisoners, who appeared glad that their fighting was over. Camps deserted and stores abandoned showed the hasty and precipitate movement of the enemy. We were told that the Hills and Longstreet were driving him down the Chickahominy. Slowly we marched during the morning towards the firing.

The enemy had been retreating all the morning, but, about 12 or 1 o’clock, he suddenly halted, turned about and offered battle. Here it was discovered that he taken up a well protected and admirably chosen position, which seemed to be fixed, ready, in waiting for him. Powerful batteries in commanding position, supported by upwards of 45,000 infantry, who were splendidly protected by ingenious breastworks, here frowned down on the advancing columns of the Confederates; and then opened one of the dearest and bloodiest battles on record—that of Gaines’ Mills or Gaines’ Farm. He had been falling back all day to occupy this position, calculating to defeat us here, and then next throw his left into Richmond.

About 2 o’clock we could hear the roar of artillery and rattle of musketry—incessant, fierce and continuous. Our faces were set in the direction of the firing. As we approached nearer, the storm of battle was borne to our ears with terrible distinctness. We moved on. Closer and closer we came to the dreadful scene of the strife. Now we are in range of their artillery, though they do not see us. Shells, bursting above, around, before and behind us, scattering their blazing fragments and sulphurous contents, remind me that we are in the tide of battle. Moving slowly along, now well within range of the batteries, a poor fellow’s head is smashed right by me, and his brains scattered on his comrades near him. We move on in a run, over ditches and marshes, swamps and fences, through open fields and thick woods, up and down hill—double quicking to the field of carnage, the harvest of death. Courier after courier arrives, urging us to hurry— our forces were hard pressed.

Gen. Lee meets us and hurries us on, as if the fate of mankind depended upon our coming. We get in striking distance of the bullets—are arranged in the order we are to go into battle. In the meantime, the tempest of the strife seemed to have been pouring out its utmost fury. The loud crashing sound of artillery, the peculiar roll of musketry, mingled with half-drowned words of command or the cries of pain of some wounded soldier borne by on a bloody litter, filled the air with their terrific sounds.

Gen. Hood and Col. Marshall conduct our Regiment; on we go in a run—the fight thickens—the noise deafens—on we go over a deep branch, meeting regiments and thousands of frightened stragglers leaving the field; some of them exclaimed as they passed us—“I wish you’d take that battery.” I never dreamed of such confusion; our ranks were broken time and again by the fleeing Confederates; really the tide of battle seemed to have been rushing madly against us. Men deserted their colors, Colonels’ lost their commands, and God only knows how far off were a rout and panic.

Suddenly we (4th Texas Regiment) faced to the front, advanced in a run up the hill, and as we reached the brow were welcomed with a storm of grape and canister from the opposite hill side, while the two lines of infantry, protected by their works, and posted on the side of the hill, upon the top of which was placed their battery, poured deadly and staggering volleys full in our faces. Here fell our Colonel John Marshall, and with him, nearly half of his regiment. On the brow of this hill the dead bodies of our Confederate soldiers lay in numbers. They who had gone in at this point before us, and had been repulsed, stopped on this hill to fire, and were mowed down like grass and compelled to retire.

It was now past 5 o’clock. When we got to the brow of the hill, instead of halting, we rushed down it, yelling, and madly plunged right into the deep branch of water at the base of the hill. Dashing up the steep bank, being within thirty yards of the enemy’s works, we flew towards the breastworks, cleared them, and slaughtered the retreating devils as they scampered up the hill towards their battery. There a brave fellow on horseback with his hat on his sword, tried to rally them. But they scarcely had time, even if they had been so disposed, for, leaping over the works, we dashed up the hill, driving them before us and capturing the battery. Thus the lines of the enemy were pierced and broken, and from that moment commenced the victory with which our arms were blessed. As we came down the first hill, Lieut. Col. Warwick picked up a Confederate flag, which some regiment had abandoned, and fell with a mortal wound—the flag in hand; he supposed it was our own; but right gallantly was ours borne through the fight by our brave Color Sergeant Francis, struck as it was by nine balls. Here also Major Key fell.

After capturing this battery, we saw there was yet work ahead. We were now in an open field; the 18th Georgia here moved up on our right; a heavy thirty-two pound battery straight ahead now opened on us with terrible effect, while another off to the right reminded us that we had just commenced the battle. On we go, leaving the battery we had just taken to be held by a small party, exposed to a galling fire from the battery in front, from that on the right and from swarms of broken infantry all on our left and rear. Yet, on we go, with not a field officer to lead us, two thirds of the Company officers and half the men already down—yelling, shouting, firing, running straight up to the death-dealing machines before us every one resolved to capture them and rout the enemy.

When we came within 800 yards of this battery, I found myself with some others, in a lane, formed by a fence and barn, here we halted a few seconds to blow. I could plainly see the gunners at work; down they would drive the horrid grape—a long, blasting flame issued from the pieces, and then crushing through the fence and barn, shattering rails and weather-boarding came the terrible missiles with merciless fury. Again we start off.

When we arrived within about 70 yards of the battery, we stopped for a moment behind a very slight mound where an old fence had stood. The smoke had now settled down upon the field in thick curtains, rolling about like some half solid substance; the dust was suffocating. We could see nothing but the red blaze of the cannon, and hear nothing but its roar and the hurtling and whizzing of the missiles. Suddenly the word is passed down the line, “Cavalry,” and down come horses and riders with sabers swung over their heads, charging like an avalanche upon our scattered lines; they were met by volleys of lead, and fixed bayonets in the hands of resolute men, and in less time than I take to write it, a squadron of U.S. Regular Cavalry was routed and destroyed. Horses without riders, or sometimes with a wounded or dead master dangling from the stirrups, plunged wildly and fearfully over the plain, trampling over dead and dying, presenting altogether one of the most sublime and at the same time fearful pictures that any man can conceive of without being an eye-witness.

The Cavalry routed, on we rush with a yell, drive the gunners off or kill them, and our battle flag waves over the battery. Still the work was not finished; the enemy had rallied behind some houses in front and in the garden, and kept up a sharp fire; we drove ahead, forced them to leave the houses, whipped them out of the garden and put them to utter rout.

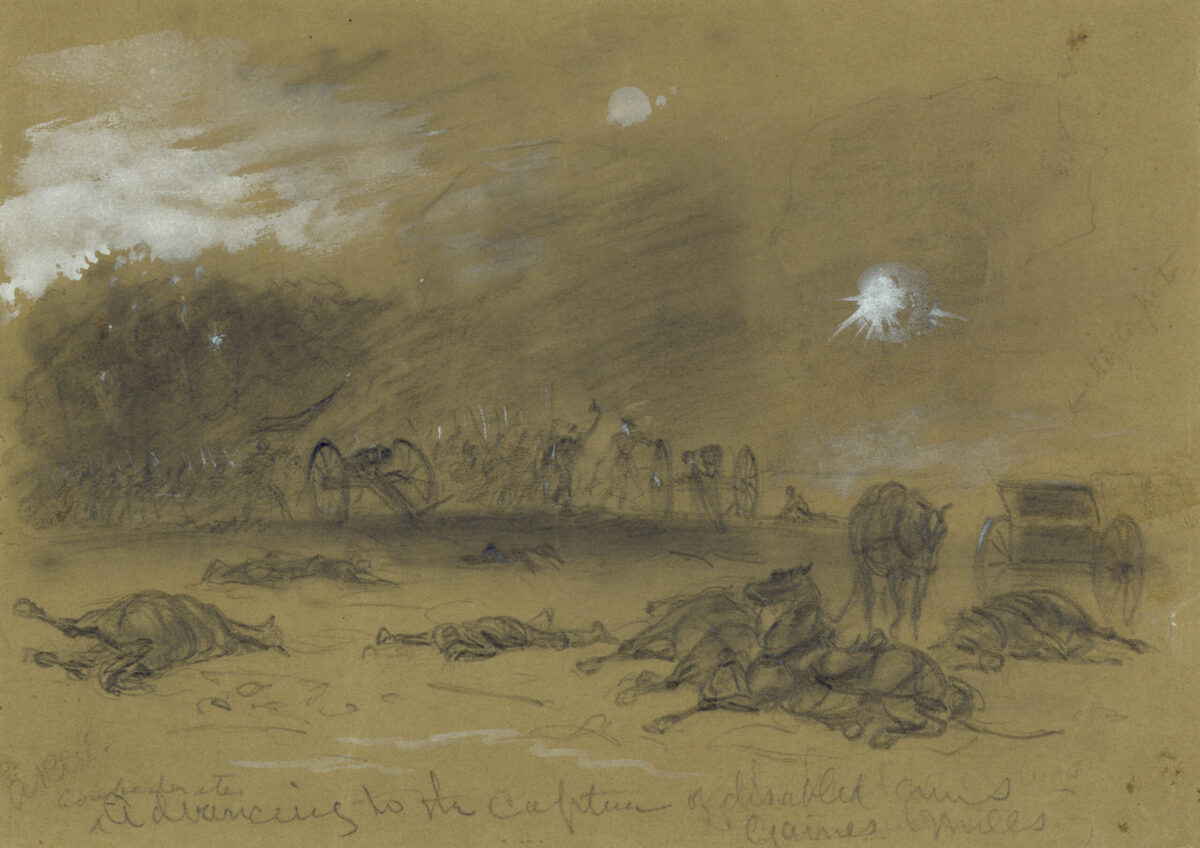

Our own Regiment, now a mere handful and led by Captain Townsend, still rushed on towards the river, until ordered back for fear of being surrounded. It was by this time getting dark. Prisoners gave themselves up in numbers. A Battalion ran into the 5th Texas Regiment and surrendered. We gathered the little squad of our Regiment that was left, formed line of battle, and prepared to sleep on the battle field with the dead and dying. As the night came on and quiet rested on the battle field, the groans of the wounded and their cries for water resounded through the night air; while glimmering lights scattered far and wide over the field told of the eager search for some brother, son or friend, or the base and heartless robbing of the dead by contemptible and merciless demons dressed up like soldiers. Finally, overpowered by fatigue we lie down on the ground and are wrapt in deep sleep.

The next morning we rose early. I will not attempt to describe the appearance of the field. I could write twenty pages and yet give you no adequate idea of it. The ground was strewn with dead and dying men and horses, with broken guns and abandoned cartridge boxes, knapsacks and blankets &c, &c.

Thus ended the decisive battle of the 27th, which broke the right wing of the enemy and consequently causes his whole vast line to give way.

Dearly did the Texas Brigade sustain the reputation of the State. And of them the 4th Texas has won immortal honor. To it is accorded, by the official reports of our Generals, the high honor of being the first troops in the battle of Gaines’ Mill to break the lines of McClellan’s chosen host. I saw men leap over the bodies of the commanders and officers and rush head-long to the enemy.

Texas need not feel ashamed of the deeds of her sons in the Virginia army; Friday’s fight has bound the brows of the gallant State with unfading laurels.

I am yours, &c.

Drew Gruber will continue researching Barziza this summer as the Lawrence T. Jones III Research Fellow with the Texas State Historical Society. He extends his thanks to the Barziza family for all their help with his research efforts.

Originally published in the June 2013 issue of Civil War Times.