Fancy footwork convinced crowds teens could chat with the dead

American Schemers

Since the birth of this great republic, millions of bored teenagers have concocted clever schemes to torment their parents, but only one teenager’s scheme became a quasi-religious movement attracting millions of followers. That teenager was Maggie Fox. The movement she spawned was spiritualism.

She did it with her toes.

In 1848, Maggie Fox was 14 and grumpy. Her family had moved from bustling Rochester, N.Y., which she loved, to a farmhouse 31 miles away in the tiny hamlet of Hydesville, which was, like, sooooooo boring.

One night, to amuse themselves, Maggie and her sister Kate, 11, tied apples to strings and bounced them down the stairs, sending their mother searching for the source of the noise. That was fun, so the girls added another trick—making loud rapping noises by moving their toe joints. That, too, set Mother Fox on a fruitless midnight search.

On March 31—April Fool’s eve—Maggie and Kate cracked their toes loud enough to wake both parents. Feigning fright, the girls blamed the noise on a ghost. Maggie clapped four times and asked the “spirit” to reply. Four raps followed as Kate cracked her toes.

“Is it a spirit?” Mrs. Fox asked the darkness. “If it is, make two raps.”

Rap. Rap.

Flummoxed, the Foxes summoned neighbors, who also fell for the toe-crack trick. Soon, hundreds were flocking to the Fox farmhouse. A rumor spread that the place was haunted by the ghost of a murdered peddler. Bent on finding the peddler’s bones, neighbors dug up the cellar floor. Maggie and Kate soon tired of their ruse but kept mum. “We could not confess,” Maggie wrote decades later, “without exciting very great anger on the part of those we had deceived.”

Word spread further. Newspapers ran stories. The local church expelled the Fox family for blasphemy and witchcraft. To escape the ruckus,

Maggie and Kate moved back to Rochester to live with their sister. Leah Fox Fish, 35, had married at 14. Her husband had deserted her and she was supporting herself and her daughter by teaching piano. When Maggie and Kate came clean about their toe shenanigans, Leah had an idea: They could make money faking a supernatural ability to communicate with the dead.

The sisters began staging séances, admission $1. After a prayer and a hymn, Leah summoned the spirits, customers asked questions, and Maggie and Kate answered by cracking their toes. Doubters scoffed but many left believing they’d communicated with departed kinfolk.

Business boomed. It was an era of spiritual experimentation. The Second Great Awakening had spawned new religions—Mormonism and Adventism, to name two—while idealists preached Transcendentalism or founded utopian communities based on primitive communism or free love or both. The newly invented telegraph had shown it was possible to send and receive information across vast distances, so maybe folks could communicate with the dead. The Fox sisters touted their séances as a “spiritual telegraph.”

In 1850, Leah booked the trio into Rochester’s largest meeting hall. At one sold-out show, skeptics rioted, heckling and throwing firecrackers. The uproar terrified the girls but the publicity made them famous. In New York City, their act attracted prominent intellectuals—journalist Horace Greeley, historian George Bancroft, novelist James Fenimore Cooper. At one séance, the girls summoned the spirit of Benjamin Franklin, who dutifully endorsed spiritualism. At another, the spirit of John C. Calhoun was asked if he favored abolishing slavery, and—shock!—he said yes.

Countless newspaper stories about the Foxes helped make spiritualism a nationwide craze. “It has spread like wild-fire over this Continent,” The New York Times reported, “so that there is scarcely a village without its mediums and its miracles.” New mediums introduced new tricks. One bowed a fiddle. Another played the piano without touching the keys. Others transcribed messages from the Great Beyond. Prominent Quaker abolitionist Isaac Post, a Fox family friend, published a book of communiqués ostensibly dictated by Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and other dead heroes.

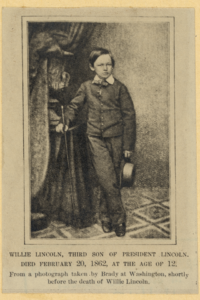

The Civil War, which killed more than 700,000 Americans, generated massive interest in summoning the dead. Mary Todd Lincoln, believing she could communicate with her deceased son Willie, held séances in the White House. Her husband was skeptical but also

tolerant of anything that might assuage his wife’s grief.

The Fox sisters ran their séance game for decades. Meanwhile, Leah married a wealthy insurance executive. Kate traveled to England, wed a barrister, and, after his death, returned to New York. Maggie fell for Elisha Kent Kane, a famous Arctic explorer. Kane, who scorned spiritualism, urged his sweetheart to “quit this dreary life” of scam séances. His snooty Philadelphia family despised Maggie’s low trade, so the couple married in secret. He soon died in Cuba.

Heartbroken by genuine loss and tormented by guilt over their mendacious money-making, Maggie and Kate took to drink. Friends arranged for them to dry out at a New York hospital but the sisters kept relapsing. Kate was arrested for public drunkenness. Maggie was found staggering soused through Manhattan during a snowstorm, searching for her dead husband.

Suddenly, in 1888, Maggie and Kate renounced the specialty that had made them famous. “Spiritualism is a fraud,” Maggie told the New York World. “It is a branch of legerdemain.” Kate called spiritualism “one of the very greatest curses the world has ever known.” Leah, rich and retired, remained silent. Before a packed crowd at the New York Academy of Music, Maggie removed her shoes and cracked her toes, demonstrating how she and Kate had made their supposedly supernatural sounds. “When I began this deception, I was too young to know right from wrong,” Maggie said. “I hope God Almighty will forgive me and those who are silly enough to believe in spiritualism.”

Leaving the spiritualist movement reeling, Maggie hit the lecture circuit. “I’ll make more money by showing people how the raps are made than I did telling lies to them,” she bragged. She had that wrong. Few people would pay to hear her confess again.

A year later, destitute and drinking, Maggie and Kate recanted their recantation. Newspapers responded with mockery but the sisters went back to staging séances, sometimes while blotto. Soon, the two drank themselves to death—Kate in 1892, Maggie six months later.

During Maggie’s brief stint as an anti-Spiritualist crusader, she published a book called Death-Blow to Spiritualism. But spiritualism never died. The phenomenon lives on in multiple forms, from the utterly respectable National Spiritualist Association of Churches to countless freelance mediums and New Age channelers like “Mystical Man” Robert Shapiro, who interviews penguins and redwoods about their alien origins and claims to be able to “communicate with any personality anywhere and anywhen.” Spiritualism, created by the Fox sisters in 1848, will no doubt survive as long as human beings yearn to communicate with the dearly departed.