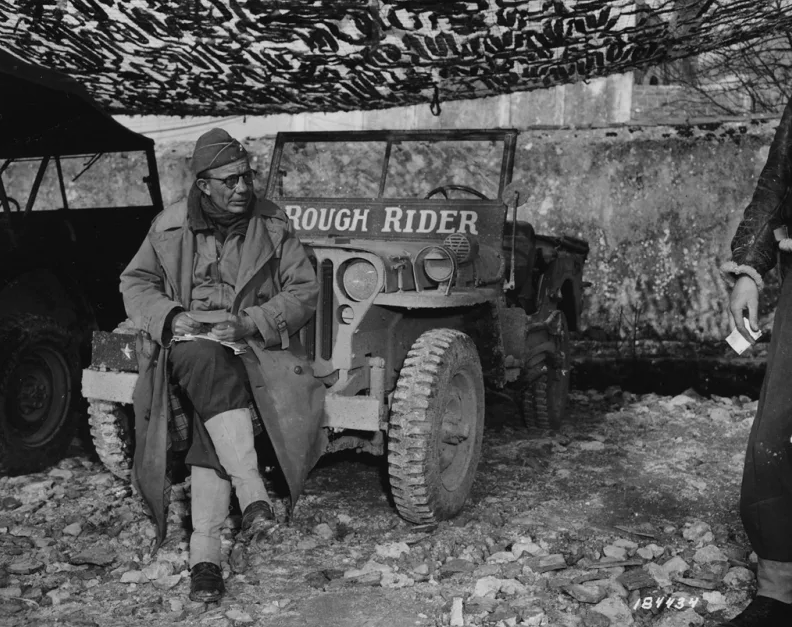

“We’ll start the war from right here!” Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. purportedly declared as his Higgins landing craft drifted about a mile from its target destination on Utah Beach the morning of the June 6, 1944 invasion of Normandy.

At the age of 56, Roosevelt, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt, was not only the oldest soldier deployed during Operation Overlord, but the highest-ranking American figure to storm the beaches.

He did so with only a cane and a pistol.

A veteran of the First World War, Roosevelt was among the first American doughboys to land in France in 1918, seeing action during the Battle of Cantigny. Reenlisting at the outbreak of World War II, Roosevelt led four amphibious assaults, from Operation Torch—the invasion of North Africa—to fighting on the beaches of Sicily and in the mountains of Italy.

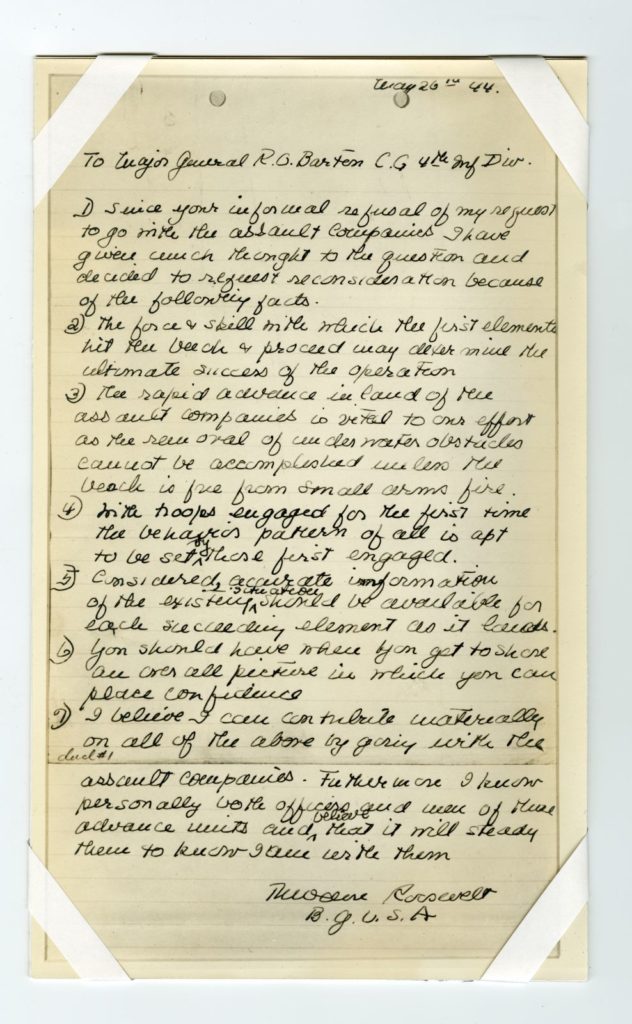

Well-liked and respected by his men, Roosevelt had to campaign hard, however, to deploy during the invasion of Normandy. His superior officer, Major General Raymond “Tubby” Barton initially rejected Roosevelt’s request to enter the European Theater and lead the 4th Infantry Division, 8th Infantry Regiment into combat. In a personal letter to Barton dated May 26, 1944, Roosevelt pleaded his case in seven succinct bullet points, noting that “I personally know both officers and men of these advance units and believe that it will steady them to know that I am with them.” Barton eventually relented.

Amid withering fire from German coastal installations, machine-gun nests, and densely packed minefields lining Utah Beach, Roosevelt remained a calm figure guiding successive waves of scrambling soldiers to the beachhead.

“He was undeniably old-fashioned, undeniably true, and undeniably the last of his father’s Rough Riders,” wrote Tim Brady in His Father’s Son: The Life of General Ted Roosevelt, Jr. According to the American Legion, Roosevelt continued to befuddle the enemy as he limped back and forth to the Higgins boats, walking stick in hand, to keep the men moving.

A sergeant from the 8th recalled encountering Roosevelt on the beach “with a cane in one hand, a map in the other, walking around as if he was looking over some real estate.”

By the end of the day, the 4th Infantry was able to penetrate inland six miles, and of the 21,000 troops that landed, there were only 197 casualties.

Roosevelt’s own son, Quentin II, was among the first wave to land at Omaha Beach, making them the only father-son duo to come ashore on D-Day. Quentin survived the war only to die in a plane crash in China in 1948.

Tragically, five weeks after the D-Day landings the beloved general died suddenly from a heart attack.

Three months later, for his cool valor under fire, Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. His citation reads:

He repeatedly led groups from the beach, over the seawall and established them inland. His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack and his complete unconcern at being under heavy fire inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice. Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brigadier General Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. Under his seasoned, precise, calm, and unfaltering leadership, assault troops reduced beach strong points and rapidly moved inland with minimum casualties. He thus contributed substantially to the successful establishment of the beachhead in France.

Roosevelt is buried in the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. His brother Quentin, who was killed in WWI, was moved to rest beside Roosevelt and remains the only WWI soldier buried in that hallowed ground.