In the early 1900s, an Indiana plowman unearthed two flint points predating Whites’ arrival in the region. The arrowheads bespoke an eons-old tradition of subsistence hunting as well as the bloody wars native nations fought to stop Americans from flooding the fertile Northwest Territory.

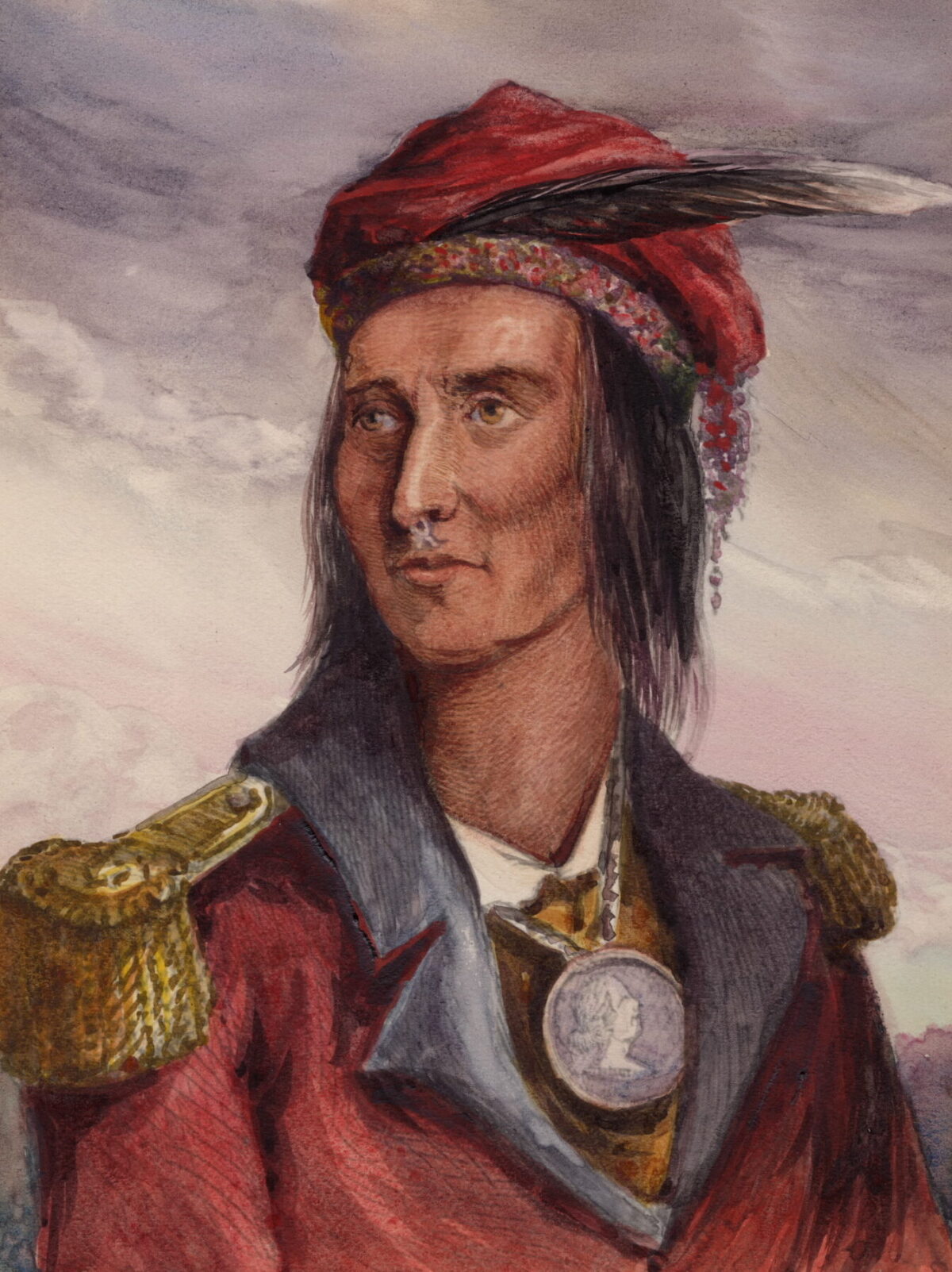

In Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation, award-winning historian Peter Cozzens admirably brings this lost world to life. His canvas is the story of two Shawnee brothers who knit rival tribes into a political and spiritual alliance meant to defend Indian land in what became the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Tecumseh was born in 1768, the year British officials and the powerful Iroquois nation signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, which was intended to keep Whites east of the Appalachian Mountains. It was a sham—the Iroquois had no right to sign away other tribes’ land and the British did nothing to stop Whites from crossing the Ohio River boundary. In 1774, when Tecumseh was six, his father died in what become known as Lord Dunmore’s War.

Tecumseh was recognized early as a natural leader and joined raiding parties, learning English from White captives. In their village, now Chillicothe, Ohio, Tecumseh’s younger brother, Laloeshiga, stood out as a braggart nicknamed Lalawethika, or “Loudmouth.”

The brothers’ youth was marked by the violence that persisted after the Revolutionary War ended in the East. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the British sold out the Ohio Indians who had sided with them, surrendering to the victors “sovereignty” over tribal territory. Disavowing the treaty but seeing the British as the lesser evil, tribal leaders accepted arms and aid from King George III’s generals in Canada.

In 1786, the recalcitrant chiefs created a pan-Indian confederacy aimed at expelling Americans from their lands. The confederacy’s greatest success came in 1791, when U.S. soldiers under hapless General Arthur St. Clair tried to “liberate” the Ohio Territory. Tecumseh, 23, missed the victory over St. Clair’s at the Battle of the Wabash but Lalawethika, 17, probably participated.

The American defeat did nothing to lessen pressure on the frontier. In 1793, a better-prepared army under General Anthony Wayne marched on northwestern Ohio. Canadian Governor General Guy Carleton had promised the chiefs Britain would support the Indians in war. Near Fort Miamis, a British stockade, disciplined American regulars surprised Tecumseh’s warriors, chasing them to the British fort, where redcoats slammed the gates in their supposed allies’ faces. The Northwest Confederacy evaporated the next summer when 99 chiefs signed the Greenville Treaty, giving almost all Indian lands in Ohio.

Cozzens explains how, as Tecumseh was solidifying his reputation as a chief, Shawnee mores, especially regarding seers and visionaries, were fueling Lalawethika’s rise. Proclaiming that he had communicated with the Great Spirit, he took the name Tenskwatawa, or “The Open Door”—a reference to closeness to the deity. He called on followers to return to traditional ways and shun Americans. He demanded acolytes swear off whiskey. The prophet’s brother began preaching this message of self-empowerment to other tribes.

Most of Cozzens’ 17 books explore facets of the Civil War, but Tecumseh and the Gilder Lehrman Prize-winning The Earth Is Weeping (2016) establish him as a leading chronicler of American Indians’ painful history.

By citing contemporaneous accounts of Tecumseh’s life, including letters and official documents, the author shows how many White Americans came to admire the Shawnee leader such that, for example, an Ohio lawyer, Charles Robert Sherman, gave his newborn son William the middle name Tecumseh.

Cozzens also explicates how White hunger for land, inextricably coupled with animosity toward natives, drove federal frontier policy from the republic’s beginnings. Tecumseh’s perfervid American enemy, William Henry Harrison, invoked the Shawnee brothers by name to bring President Madison to declare war on Britain in 1812. Harrison won the presidency in 1840 on the popularity of the campaign song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” which trades on Harrison’s history as an Indian fighter.

Cozzens’s descriptions of Tenskwatawa’s spiritual agenda, centered on Indian independence and rejection of White culture, will remind readers that tribal leaders from Osceola to Sitting Bull attempted to preserve native culture with the weapons of war. The tragedy of their failure haunts America today. —The arrowheads shown, likely made by the Miami tribe, came to American History senior editor Nancy Tappan as family heirlooms.