The U.S. Army of the mid-1850s was rigidly stratified between officers and enlisted men. The military hierarchy of the period was more immutable than that of nearly any other institution in America, except perhaps the relationship between master and slave. Each soldier had his place in a society structured by rank. The officers, as a rule, considered themselves an aristocracy, superior to those under their command. They viewed the enlisted as a servile force, there in part to ensure the status of commissioned officers. Buttressing their authority was the absolute power of military courts to try offenders—especially enlisted men.

An Army bugler who wrote breathless letters home about riding out West with horse soldiers is perhaps the last man you would expect to disrupt the military caste system, much less face a Virginia noose six years later for committing armed terror at the side of a half-mad bearded prophet. Indeed, Aaron D. Stevens boasted in a November 1854 letter to sister Lydia that his daring adventures with the 1st U.S. Regiment of Dragoons in New Mexico Territory had prevented him from writing since the patrols began in April. His unit, Company F, had already experienced “two fights with the Patches [Apaches], this year and had 9 men killed & 10 wounded…and as luck would have it, I have got off safe so far, but they may get me yet.”

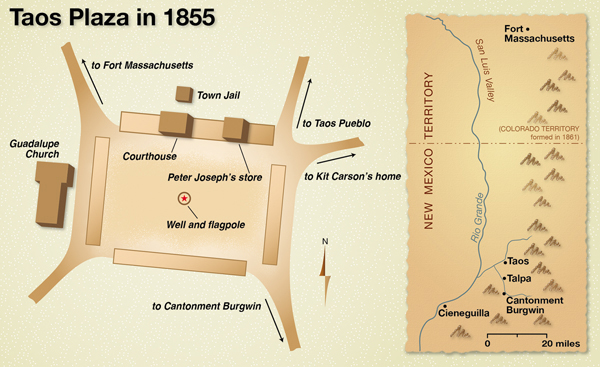

Within a few months this son of a Connecticut church choirmaster and more than a dozen comrades would riot against a superior officer in the dusty Taos Plaza. Stevens and three other soldiers escaped execution when President Franklin Pierce and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, citing mitigating circumstances, commuted their death sentences to three years of hard labor. In a unique turn of events the Army cashiered the company commander for chronic intoxication, ordered the demotion and transfer of the company’s noncommissioned officers and the transfer of its enlisted men to other New Mexico units, subjected the company’s first lieutenant and the squadron’s commanding officer to courts-martial and, for good measure, exiled the regiment’s major from New Mexico Territory.

The 1855 mutiny was as out of character for Company F as it was for Stevens. The unit was regarded by many as the most elite company of the 1st Dragoons, the most elite regiment in the Army. Major General Winfield Scott, who had commanded the invasion of Mexico during the 1846–48 Mexican War, had selected Company F as his bodyguard. Company F’s heroic charge during the Battle of Churubusco had cost its commanding officer his left arm and eight men their lives but had nearly breached the enemy lines at the gates of Mexico City.

The regiment had paid a high price for its accomplishments—deaths, illnesses, injuries, transfers and the resignations of many of the regiment’s best officers and men. As one officer observed, “No regiment of the Army has paid so heavy a quota to the war with Mexico as has the 1st dragoons.” During the postwar years the shuffling and loss of officers in combination with the increased territory the dragoons had to cover placed a heavy strain on the regiment. The replacement officers were often inferior to their predecessors. Nowhere was this more apparent than in New Mexico Territory, where Colonel Thomas T. Fauntleroy became commander of the 1st Dragoons. A political appointee with an undistinguished military record, Fauntleroy had nevertheless received rapid promotion to the rank of colonel, which, according to one dragoon sergeant major, had distressed “many better qualified officers.”

Of more immediate concern to the men of Company F was Fauntleroy’s assignment of the severe Major George Alexander Hamilton Blake. Under Blake’s command the men traveled north in June 1852 to build a new post, Fort Massachusetts, in the remote San Luis Valley (in present-day southern Colorado), 85 miles northwest of Taos. Blake pushed his troops to the limit in this most uninviting place. Winters in the San Luis Valley saw snow on the ground from October through March and temperatures plunging to 12 below zero. Such statistics were of little concern to the Army command.

“The men were overworked at Massachusetts,” said post surgeon Edmund Barry. “I have known Major Blake to refuse passes frequently to deserving men, which I conceived to be owing to partial spite and spleen.…The company in general hated Major Blake, and I suppose the reason was because he kept them all the time at work and allowed very few privileges.” Blake rarely gave any man a pass without dressing him down, though he reportedly absented himself for frequent unofficial trips into Taos. No doubt the men at Fort Massachusetts felt they had good reason to hate their commander.

Blake’s unyielding manner, combined with the Army’s orders to erect a fort during the harsh winter of 1852–53, pushed the troops to the breaking point in fall 1853. Departmental command discovered that due to the short growing season and the difficulty of shipping forage to Fort Massachusetts, there would be insufficient provender for the horses in the coming winter. It ordered Company F to move south to the slightly warmer clime of Cantonment Burgwin, 10 miles south of Taos. Leaving for a warmer place might have sounded good on the surface, but the men had worked hard to build Fort Massachusetts. To many of them it made no sense to abandon the place.

“The prospect of abandoning the position soon after he has made it comparatively comfortable leaves [the soldier] without an adequate inducement for the sacrifice he is called on to make,” Secretary of War Davis wrote in 1856. “A laborer without pay or promise of improvement in his condition, a soldier without the forms and excitement of military life, it is hardly to be wondered that this state of things should lead to desertion.”

A few days prior to the unit’s scheduled migration south, the men’s smoldering anger came to a head. Full of frustration over their Army lives and full of hatred for Blake, the whiskey-fueled men let it all out on the parade ground (details of this mini-riot are sketchy at best). A shaken Blake shut himself up in his quarters and made no effort to stop the noise, drunkenness and insubordination.

The next spring Company F saw combat and suffered devastating losses at the hands of the Jicarilla Apaches in the Battle of Cieneguilla. On March 30, 1854, 1st Lt. John Wynn Davidson was commanding a reinforced company under orders to locate a fugitive band of Jicarillas and keep them from fleeing westward across the Rio Grande. He disobeyed orders by attacking the Jicarilla camp on a ridge near Cieneguilla (present-day Pilar, N.M.). Davidson and his men soon found themselves surrounded in a basin below the village, and every member of the 15-man Company F detachment was killed or wounded in the fight (see “The Battle of Cieneguilla,” by Will Gorenfeld, in the February 2008 Wild West).

The hard campaigning of 1854 left the exhausted men of Company F with threadbare uniforms, played-out horses and damaged equipment. Yet Colonel Fauntleroy planned to send Company F back into the field early the next year. On the morning of March 8, 1855, Captain Philip Thompson led the 55 men of Company F out of Cantonment Burgwin for a planned rendezvous with Fauntleroy’s column. Thompson rode only a few miles before halting at Ceran St. Vrain’s mill and distillery in Talpa, south of Taos, to procure cornmeal for the horses and Taos lightning (whiskey) for the men.

Several Company F soldiers were drunk when they entered Taos and, procuring alcohol in local saloons, became drunker. One trooper galloped his horse through a gathering of Mexicans and then tried to ride up the steps of Peter Joseph’s store. The horse stumbled and fell, throwing its rider. Civilians roared with laughter at the antics of the drunken soldier, which increased tensions between the troopers and townsfolk. They were soon trading shouts and taunts across the plaza.

Fearing the worst, New Mexico Territory Supreme Court Associate Justice Perry E. Brocchus went to the plaza, where he sensed “a suppressed spirit of mutiny in the majority of the soldiers.” Entering Joseph’s store, he found Major Blake seated at a desk, writing reports and oblivious to the commotion outside. The major assured the judge he would quickly put a stop to the disorderliness.

Blake then ordered Thompson to take the detachment out of town as quickly as possible. Thompson instructed 1st Sgt. Thomas Fitzsimmons, a tough and capable 26-year-old veteran from Westmeath, Ireland, to gather the troop to depart. Bugler Stevens sounded “to horse,” and most troopers dutifully answered the call, prepared to mount and then mounted, forming an extended line across the plaza.

Thompson still had to round up the drunken revelers who had not responded to the bugler’s call. Private Jeremiah Sullivan, a three-year veteran who had been seriously wounded at Cieneguilla, was lying on the ground, too intoxicated to mount much less ride. The captain, who was often under the influence himself, ordered Fitzsimmons to lift the “d_____d rascal” onto his horse and tie him to the saddle.

Fitzsimmons, who often oversaw Company F when Thompson was indisposed, hefted Sullivan into the saddle, but the intoxicated soldier rolled off and fell to the ground. When the sergeant helped him to his feet and tried again, the confused Sullivan resisted, prompting a warning from Fitzsimmons not to make trouble. “You son of a bitch, you are always down upon me,” complained Sullivan. Fitzsimmons responded by thumping Sullivan in the face.

Blake, standing nearby, was not pleased. He protested the sergeant’s rough treatment of the drunken trooper. Fitzsimmons claimed he was defending himself. Blake answered that Sullivan had never struck the sergeant, and he then ordered Thompson to arrest Fitzsimmons. The unsteady Thompson, obviously in need of the sergeant’s services, refused to comply with Blake’s order. “Very well,” barked the major, walking over to Fitzsimmons, “You are placed under arrest.” Blake then shouted at Thompson, “I order you to take your company out of town immediately, or if you do not, I will march the company out myself!” When the captain was slow to respond, Blake walked to the front of the assembled troop and told the men he was taking immediate command.

Blake’s actions—arresting the sergeant and stripping the captain of his command—were what set off the subsequent riot. “I am well aware that there was such a feeling in the Company against Major Blake,” surgeon Barry later stated. “It was like gunpowder—it required but a spark to explode it.”

Intoxicated Private John Cooper rode up and told the major that the men in the company were tired of being driven like slaves, and that it was time to give the company some slack. Blake had long detested Cooper. Now the major pulled him from the saddle, seized his collar with one hand and struck him two or three times with the other hand. Dazed but not defeated, Cooper fought back. He grabbed Blake’s collar, yanked the major’s hair, bit him, then began kicking and punching him. And then, oh, what an eruption occurred.

Although certainly not hampered by the Marquess of Queensbury rules (which, in fact, would not govern boxing until the 1860s), the riot that followed did seem to include a strange sense of decorum. The company was filled with well-armed, combat-tested veterans who detested the major and wanted to see him get a sound thrashing. Yet reportedly none of the assailants used a weapon on Blake. Nor did the major use a weapon with deadly intent on any of his attackers. He did take a saber from Captain Thompson’s scabbard and strike Private Cooper three times with the flat of its blade. And during the fight someone else handed Blake a pistol, but the major tossed it away, fearing that if he used it, he would surely be killed. In short the major sensed his life was not in danger as long as he did not use deadly force himself.

Strikingly, neither Thompson nor any of the noncommissioned officers came to Blake’s aid. First Lieutenant Robert Johnston mounted a halfhearted one-man rally. But when the lieutenant started to draw his saber, powerfully built Corporal Jim Vanderven caught Johnston by the shoulder and warned him against it lest the mutineers kill him. The lieutenant sheepishly retreated to the left flank of the troop.

Among the onlookers was famed frontiersman Christopher “Kit” Carson, who reportedly feared nothing and was said to respond to danger “with a preternatural swiftness.” A dragoon sergeant once described him as being “ever ready to sacrifice his all for a friend in need.” But on this day Carson peered cautiously around a corner, saw that nobody was dashing forward to assist the fallen and battered Blake, calculated the odds and decided not to confront the furious soldiers.

One brave soul—Blake’s trusted servant Ramón Baca—finally did intervene. Risking his own safety to help his patron, Baca rushed into the struggle and kicked Cooper in the neck. The private released his hold on Blake and yelled for his comrades to “kill the son of a bitch!” Four soldiers answered his call. One struck Baca twice with the knuckle guard of a saber while the others hit the servant repeatedly with carbine butts, rendering him unconscious.

Sergeant Fitzsimmons’ sense of duty finally overcame his lack of sobriety and his anger over being arrested by Blake. With pistol in hand and Vanderven by his side he rushed forward to break up the fight. “Look out, sergeant, or you’ll get hit or hurt!” someone yelled as saber-wielding trooper Joseph Fox knocked the pistol from Fitzsimmons’ hand. The sergeant fended off several more saber blows with his forearm, suffering minor cuts. Noticing Private Robert Johnson riding toward Blake with pistol drawn, the sergeant browbeat Johnson to get back in the ranks. The private obeyed.

But the drunken rioters were not done. After Blake escaped Cooper’s clutches, trooper John Steele grabbed the major’s neckerchief, pulled Blake to the ground and began to beat him. At that point another Blake ally emerged—Judge Brocchus. He later recalled seeing the major rolling on the ground and fighting a “stout athletic soldier” while Thompson merely looked on in a “state of total inertness, manifestly paralyzed in his energies.” Compelled to act, the judge waded into the fray and shoved aside Steele. Brocchus then dragged Blake to the portal of Peter Joseph’s store. Dazed and bruised, his uniform caked in brown dust and blood, the major slowly rose to his feet and identified the three troopers who had attacked him. Taos County Deputy Sheriff Ezra Depew, a former dragoon, aided by the noncommissioned officers, quickly arrested and escorted the accused to the town jail.

Though the plaza was now quiet, tensions lingered. Blake was, in the words of Brocchus, “evidently in very high blood and laboring under a sense of outrage and wrong.” The judge gently placed his arms around Blake. But the major was not ready for any tenderness. He berated Captain Thompson and Lieutenant Johnston for not coming to his aid, claiming they wanted to see him killed. The whole sorry affair might have ended right there had the angry major left the plaza to deal with his injuries. Unfortunately, Blake boasted: “I can whip or thrash any man in this company from right to left. Either with gun pistol or saber, and now if there is any one of you thinks yourself fit, step out here, and I will show you whether you can call old Blake a coward or such.”

During the fight bugler Aaron Stevens had stood calmly at the center of the Company F formation holding Johnston’s and Thompson’s horses. As he led the horses to their riders, Stevens heard Blake’s challenge. The major’s acerbic manner and mistreatment of those in the ranks had long bothered the bugler. He threw down the reins, drew his Colt Dragoon revolver and called out to Blake: “You can’t back out the company that way! I’m one of the worst men in it, and I’ll accept your challenge either with gun, pistol or saber.”

Blake apparently didn’t hear Stevens. Neither did Brocchus, but the judge feared the major’s reckless bluster could reignite the riot. He saw Stevens standing there and asked the bugler to apologize to Blake on behalf of the troop. Despite his anger at the major, Stevens was willing. But when he offered an apology and then tried to explain why he and the men were so upset, Blake refused to listen. The judge asked the bugler to try again. But Stevens had no better luck. The major told the bugler he and many of the others had behaved badly. Blake then repeated he was not afraid of Stevens or anyone else in the company.

“God____ you!” Stevens snapped. “I’m as good as you are and will blow your godd____d heart out!” Stevens raised his Model 1851 Sharps carbine, cocked the hammer and pointed the muzzle at Blake’s chest. It was then Kit Carson jumped in, with Brocchus’ help wresting the carbine from Stevens’ grasp and placing him under arrest.

The dust settled after Stevens’ arrest, and a somber Lieutenant Johnston led the remainder of Company F out of town. In the ensuing weeks the company participated in a series of skirmishes in the southern Rockies. When the campaign ended, Company F returned to quarters at Cantonment Burgwin.

Though they had risked their lives in battle with Indians, eight of the enlisted men were named as participants in the mutiny and faced general court-martial. Captain Thompson was cashiered from the service for lashing out while intoxicated at the proceedings. Farrier Edward O’Meara and troopers William Gray, Robert Johnson, Adam Williams, Daniel McFarland, Henry Jacobs, John White and John Harper all ended up in confinement for their part in the mutiny. A few other soldiers suffered garrison punishment, a few weeks of hard labor and the loss of a month’s pay for their misdeeds in the plaza.

A far worse fate loomed for troopers Aaron Stevens, John Cooper, Joseph Fox and John Steele. The Army charged them with mutiny and sought the death penalty under Article 9 of the Articles of War. Their court-martial hearings began in Taos May 21, 1855, with Colonel Fauntleroy heading the court-martial panel of eight officers. The legal odds were stacked against the enlisted men. They were unrepresented by counsel, the triers of fact were officers, and the judge advocate needed but a two-thirds majority to gain a guilty verdict. The accused’s cross-examination of the witnesses was pro forma. The judge advocate had no difficulty securing four convictions.

But that was not the end of the case. As required by law, the transcripts of the court-martial hearing were sent to the president and secretary of war. On August 9, 1855, President Pierce commuted the death sentences of the four men and resentenced them to three years of hard labor. The president further ordered that Blake and Johnston be court-martialed. Pierce concluded that Blake had been “greatly responsible for that utter want of discipline which would have cost him his life in this mutiny, if he had not been rescued by civil authority.” He additionally commanded that Company F be broken up and its men sent to serve with other companies.

Half of the enlisted men in the former Company F were professional soldiers. Despite their mistreatment by Blake, many of them re-enlisted. Sergeant Fitzsimmons lost his stripes and found himself in Company K. Apparently detested by certain soldiers for bad behavior and dishonesty, he suffered a beating in October 1855 severe enough to require a stay in the Fort Union hospital. Fitzsimmons, nonetheless, re-enlisted in the 1st Dragoons, and by the end of the Civil War he was again serving as a sergeant, with Company A of the 1st Cavalry (the former 1st Dragoons).

In 1863 trooper Fox, one of those initially condemned to death, was in Company K, fighting at Gettysburg. Farrier O’Meara, who was placed in custody following the riot, twice re-enlisted, saw combat with the regiment in the Civil War and was honorably discharged in 1867. Fitzsimmons and trooper Gray (both of Company K) were subjected to another court-martial in 1856 for attacking the sergeant of the guard. Gray remained in the service and at the outset of the war was serving in Company K of the 1st Dragoons at Fort Tejon, Calif.

Blake, in contrast to the others caught up in the courts-martial, dug into his fortune and secured competent counsel. Lieutenant Colonel John B. Grayson and Judge Joab Houghton overwhelmed the unskilled judge advocate and successfully argued for the dismissal of a number of badly pleaded charges on procedural grounds. On June 12, 1856, Blake was adjudged guilty of failure to discipline Thompson for not arresting Fitzsimmons and for not doing all he could to suppress the mutiny, but the court acquitted the major of all remaining charges. The panel sentenced him to suspension without pay for a year. Blake had served just a month of his suspension when Brev. Brig. Gen. John Garland intervened and, under the authority of the 112th Article of War, restored Blake to active duty. He was ordered to accompany headquarters and two companies of 1st Dragoons on their march from New Mexico Territory to California, where they were to garrison Fort Tejon. Having suffered but a slap on the wrist for his role in the mutiny, Blake remained in the service, gaining the rank of brevet brigadier general for his gallant service during the Civil War.

The Army accused Lieutenant Johnston of having violated the Eighth Article of War by failing to use his utmost endeavor to rescue Blake and to suppress the 1855 Taos mutiny. His court-martial began on February 6, 1856. Following a three-day hearing, much to the consternation of General Garland, the court acquitted him. At the outset of the Civil War, Johnston resigned his Army commission to become a Confederate colonel, serving in the 3rd Virginia Cavalry.

Bugler Stevens, who had escaped hanging for his part in the mutiny, became a militant abolitionist. Taking on the alias “Colonel Whipple,” he joined James Montgomery and his free-state group in Bloody Kansas. Stevens soon became a member of John Brown’s notorious band, and on October 16, 1859, he participated in Brown’s abortive raid of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Va. (present-day West Virginia). After Virginia militiamen trapped Brown’s raiders in the town’s fire engine house, it was Stevens who emerged to seek a truce. He was instead shot and captured. Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee’s detachment of U.S. Marines then forced its way into the engine house and took Brown and his surviving men captive. This time, despite sister Lydia’s pleas, Stevens would receive no presidential pardon. On March 16, 1860, though still badly wounded, Stevens was hanged for treason.

Seldom do collective attacks by enlisted men against an officer appear in the U.S. Army annals. What makes the Taos mutiny unique is that more than a dozen men manifested their pent-up rage against a commanding officer in a brutal assault. Also unique is that the commissioned and noncommissioned officers present, whether too frightened to lend aid or just sympathetic toward the enlisted personnel, initially took no action to rescue the major. The 1855 event, with its rich court-martial transcripts, provides rare insight into the uncaring officers in general, and officers like Blake in particular, who drove men of an elite unit to mutiny.

California authors Will and John Gorenfeld write often for Wild West. Will contributed to the 2014 book Battles and Massacres on the Southwestern Frontier: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, edited by Ronald K. Wetherington and Frances Levine. Suggested for further reading: Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848–1861, by Durwood Ball.