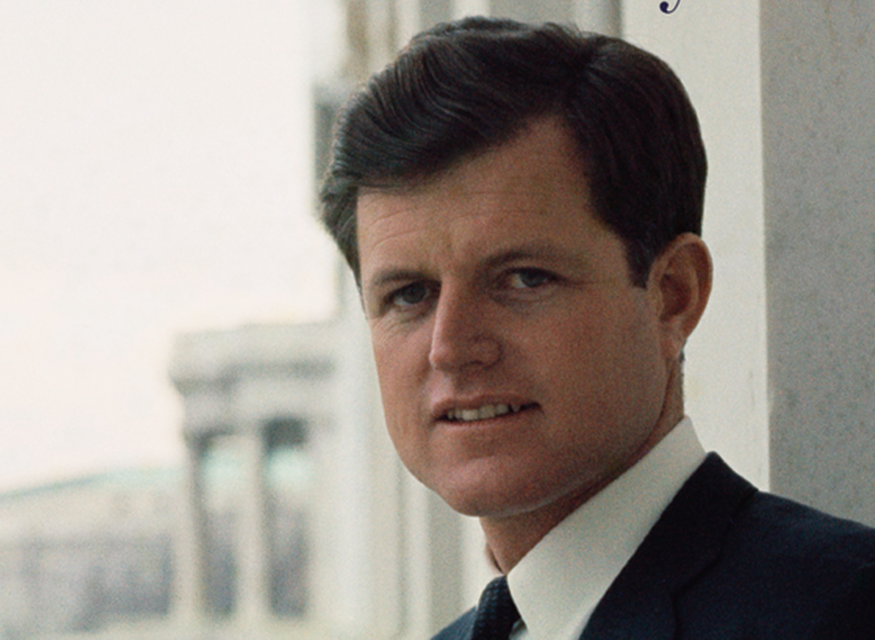

A U.S. senator for 47 years, Edward M. Kennedy (1932-2009) is recalled mostly as the youngest and only unmurdered of three famous political brothers, as well as something of a black sheep. Needless to say, there’s more to him. Editor Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia, overseeing 500 pages of interviews with an elderly Kennedy and his intimates, delivers a revealing portrait of two generations of American politics.

The last of nine children in a wealthy and competitive family, Edward, 15 years brother John’s junior, worked hard and mostly futilely to gain household notice. Harvard admitted him because of his influential father, not his brains, then, catching him cheating, suspended him for two years. Harvard Law being less amenable, he attended the University of Virginia law school. His grades remained mediocre, but he worked hard, graduating in 1959, having established himself as an enthusiastic campaigner by helping in John’s 1958 Senate re-election campaign. He successfully managed the western states in JFK’s 1960 presidential run. Neither Jack nor Bobby was happy at Teddy’s 1962 decision to seek JFK’s former Senate seat, but they came around.

An ill-starred decade followed. Bullets claimed Jack in 1963 and Bob in 1968. A 1964 air crash nearly killed Ted. Campaign worker Mary Jo Kopechne’s 1969 death by drowning in Kennedy’s car blighted his presidential ambitions. Four years later bone cancer cost his son a leg.

Regardless of Kennedy’s rakish national reputation, Massachusetts voters always re-elected him with large majorities. He became a veteran Hill insider and the Senate’s most widely recognized liberal member. Can anyone name his successor?….

Kennedy’s successful fight for the 1965 Hart-Celler immigration law, which replaced a notorious 1924 measure, received less ink and airtime than LBJ’s civil rights and voting reforms but changed America no less than they did. His support of legislation for women’s rights, gay rights, and national health care and against housing bias mark Kennedy as the last exemplar of a progressivism that flourished from the New Deal to the Great Society and is now quiescent.

Makers of this admirable series boast of editing minimally. Scholars will approve, but because hardly anyone speaks in grammatical sentences transcripts like these are tough reads. Readers may prefer to focus on Perry’s lucid introductions, skim the often rambling and repetitious verbatim record, and read an excellent biography such Peter Canellos’s Last Lion, or wait for a historian to refine this valuable raw material.

—Mike Oppenheim writes in Lexington, Kentucky.