New biographers shed light on Grant, who fought inner battles, too

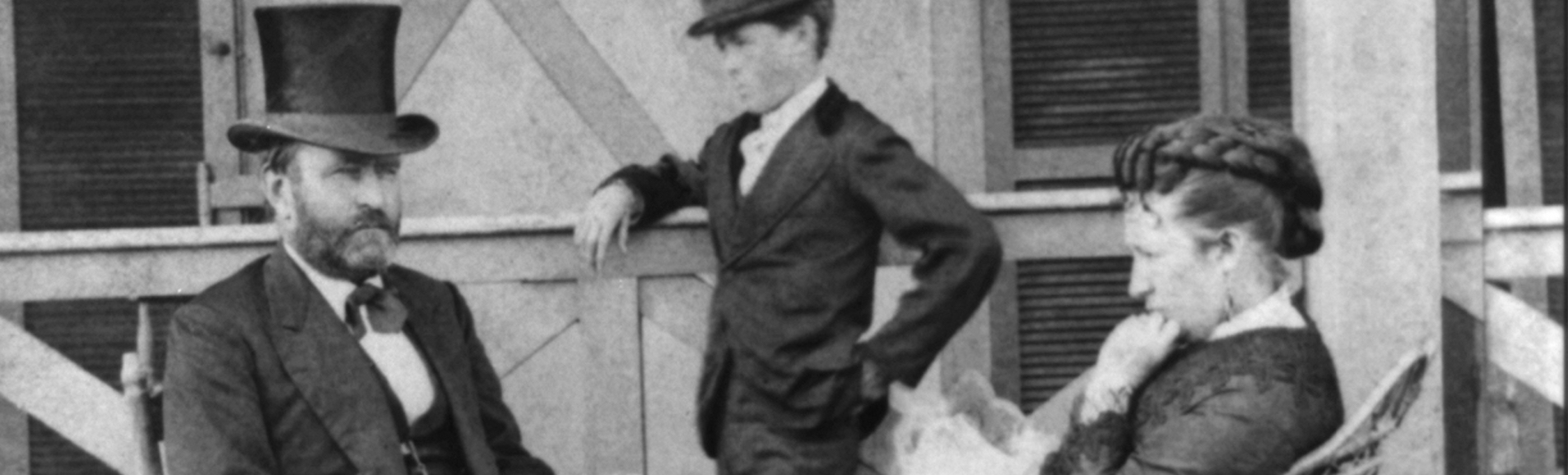

Ulysses S. Grant died a hero in 1885, but soon historians were casting him as a butcher in war and as president a weakling unable to stem

corruption consuming his inner circle. Besides, they said over and over, Grant was a drunk.

Now new biographers, including Ron Chernow and Ronald C. White, are analyzing the enigmatic Grant, clearing away some of the mud slung at him and reintroducing a historical figure worthy of more compassion and regard.

White rehabilitates Grant, citing his wartime leadership and reminding readers that as

president he championed civil rights for freedmen and Native Americans and reset the nation’s damaged relationship with Britain. At home, Grant resisted inflationary urges that would have helped western farmers but undercut the credit markets now recognized as the most powerful engines of economic growth.

Recounting Grant’s war, White hews to familiar denials about his drinking, quoting letters and reports by Grant’s official family and laying blame for his questionable reputation on jealous Union generals and sensationalist newspapermen. White casts Grant’s wife, Julia, as the temperance enforcer whenever they were together.

Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Ron Chernow more completely addresses Grant’s demons. He nails him as an alcoholic, showing the protective role played by chief of staff General John Rawlins, who more than anyone, including Julia Grant, kept the general

as sober as he was capable of being. Chernow ties Grant’s failings to insecurities seared into him by conniving father Jesse Root Grant and religious zealot mother Hannah Simpson Grant. Throughout life, Ulysses so feared rejection that anyone offering the semblance of friendship got gratitude and loyalty, even when proven corrupt.

The landslide winner of 1868 should be recalled for his civil rights record, not his senior advisers’ well-known Gilded Age venality. What is sometimes lost is that many of his betrayers

were either kin or cherished comrades in arms. It is painful to read how often evidence of aides’ malfeasance astounded the president.

The canonical explanation for Grant’s blindness to perfidy is that, being an honorable man, he took on faith that others were as upright as he. White and Chernow point to another defining trait: hatred of confrontation—a hallmark of the abused child.

—Nancy Tappan is senior editor of American History