This article, which originally appeared in the April 2010 issue of Wild West Magazine received the coveted Western Heritage Award (Wrangler) in the Magazine category.

Young Robert Haslam started as a simple laborer, building way stations for the fledgling Pony Express, but he was soon offered an opening as an express rider—an offer he eagerly accepted and a job at which he quickly excelled. On May 10, 1860, he left his home base at Fridays Station—on the present-day border between California and Nevada—and had little difficulty on his 75-mile run east to Bucklands Station. But by the time the wiry 19-year-old completed his assigned run, the situation had changed.

‘Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert pony riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred’

The Northern Paiutes were on the warpath, just one month after the Pony Express began service, and the next rider scheduled refused to get in the saddle. Haslam, however, remained undeterred by the Indian scare. Transferring the mail and himself onto a fresh mount, he galloped off on the next leg of the route, a ride that would put Haslam’s name in the history books. Riding over alkali flats and parched desert, he pushed through to Smith Creek, where, after 190 miles, he slid off of his pony for a brief rest before making the even more harrowing return run. Arriving at Cold Springs, Haslam found that the Paiutes had burned the station, killed the keeper and run off the relief horses. By the time he made it back to Fridays Station, “Pony Bob” had covered more than 380 grueling miles. Haslam made another famous ride in March 1861, carrying President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address 180 miles from Smith Creek west to Fort Churchill in a record 8 hours and 10 minutes. His dedication was exceptional, but he was not alone. Many Pony riders were willing to risk their backsides to deliver the mail in a timely fashion.

It has been 150 years since one of the most remarkable enterprises in American history carried the mail and the day. Yet, most of us can easily imagine these lone young riders racing the wind across the open plains, fleeing Indian pursuers. Yes, the Pony Express still stirs the imagination, conjuring a romantic but gritty picture. Look a little closer, though, and something else becomes clear: The Pony Express was, despite the Herculean efforts of Pony Bob and his fellows, also a terrible flop.

It is not difficult to find a failed business whose name lives on long after its collapse. History is replete with financially ruinous ventures and misadventures—from Edison Records to Betamax, from Swissair to Titanic’s White Star Line, and from Charles Ponzi to Bernie Madoff. What is remarkable is for a failed business to be remembered not for its disappointing performance but for its determination and grit. For such a venture to be romanticized, commemorated and held in awe by the public is high praise indeed. That is the legacy of the Pony Express. On the sesquicentennial of the first ride (and, on that of the last ride, less than 19 months off), much of the nation is celebrating and singing the praises of a small group of men—many of them mere boys—who set out to provide a service that ultimately proved an economic failure.

The Pony Express started out as a very good idea. Founders William Russell, Alexander Majors and William Waddell, despite popular myths to the contrary, were not rough drovers or confidence men. Rather, they were well-established businessmen with a successful record of providing freight service to both the U.S. Army in the West and civilian mercantile efforts, which included the movement of merchandise over the Santa Fe Trail. These men recognized a need for improved communications between the Eastern United States and the burgeoning communities in California. With more than a half-million people already settled west of the Rocky Mountains, and the growing likelihood of a Civil War, the federal government was determined to establish and maintain more regular contact with an area rich in natural resources and susceptible to disruptive inroads by an increasingly belligerent South.

Russell, Majors and Waddell also saw an opportunity to compete for a million-dollar government contract for dedicated mail service to the region. The partners planned to fulfill the contract with their already established Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company, of which the proposed Pony Express would be a subsidiary operation. From a business perspective, the enterprise seemed solid, especially considering the likelihood of Civil War. In wartime, service demands would surely skyrocket, and the resultant profits were bound to be enormous.

With these considerations in mind, Russell, Majors and Waddell set out to create the infrastructure that would allow them to pull off this daring scheme. Whereas communications links were good from the East Coast as far west as Missouri, anything from Kansas westward was problematic at best. Thus the challenge for these entrepreneurs was to come up with a support system to facilitate their plans.

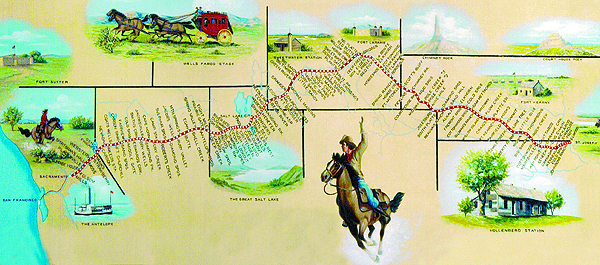

They established a headquarters at the Patee House in St. Joseph, Mo., and selected a trail that ran west from St. Joe over the existing Central Overland route—to Marysville, Kan., northwest along the Little Blue River to Fort Kearny (near present-day Kearney, Neb.); from there along the Platte River Road and across a corner of Colorado Territory before swinging north to pass Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff and reach Fort Laramie (in what would become Wyoming); then up to Fort Caspar, through the South Pass to Fort Bridger and on into Utah Territory. The final leg went through Salt Lake City, on into Nevada and across the Sierra Nevada, finally ending in Sacramento, Calif. From Sacramento the mail would be forwarded by steamboat to the Pony Express offices in bustling San Francisco. The total distance covered would amount to nearly 2,000 miles.

Some stagecoach stations were already up and running, but the partners would have to place and construct many more. Ultimately, about 190 way stations covered the route, each spaced from 10 to 15 miles apart—the approximate range a medium-sized horse could sustain at a gallop. Some of these stations would become fairly elaborate affairs, comprising stables, bunkhouses, even taverns and a post office. Most, however, would remain rudimentary structures, offering a single-story cabin for the station keeper, a corral and a roughed-in shelter for spare horses. Establishing the stations was only the first step. Each would have to be equipped and manned. The service would require 400 station hands, including skilled farriers, as well as 500 horses and at least 200 riders.

Considering the combined weight of the mail and the gear to be carried at a gallop by each horse, the riders would necessarily have to weigh no more than 125 pounds. Waddell published ads for riders and others, but the oft-reprinted flier WANTED: YOUNG, SKINNY, WIRY FELLOWS NOT OVER 18. MUST BE EXPERT PONY RIDERS WILLING TO RISK DEATH DAILY. ORPHANS PREFERRED was probably a later concoction.

These wiry young fellows would be expected to ride at a gallop the 10 to 15 miles between way stations, quickly change mounts and repeat that pattern until they reached their other “home station,” between the 75- and 150-mile mark. At this point, the next rider would take charge of the mail and begin his run, the idea being to move the mail from St. Joseph to Sacramento in 10 days. It could be a grueling job—tough on both men and horses—and thus the wages offered, $25 per week, were high at a time when an unskilled laborer received an average of $1 per day for 12 hours of work. While the work of a Pony rider was both strenuous and dangerous, it was not considered an excuse for bad behavior. Each rider had to swear an oath to conduct themselves honestly and refrain from cursing, fighting or abusing their animals. Each was then issued a small leather-bound Bible.

“Pony Bob” Haslam’s heroics stand out, but plenty of other venturesome young men answered Waddell’s summons. Among them was Missouri horse racer Johnny Frey (often spelled Fry), who would later enlist in the Union Army, only to be shot down by Rebel guerrilla “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s followers at Baxter Springs, Kan. He is often credited with being the first rider to head west out of St. Joseph, on the evening of April 3, 1860, although that remains in dispute. Others—including Henry Wallace, Billy Richardson and Alex Carlyle—also claimed to have been the first to gallop westward.

The first rider heading east out of Sacramento was probably William Hamilton. Restless young William Frederick Cody—who would go on to win fame as scout and showman “Buffalo Bill”—either rode for the Pony or did not, depending on whose version of events you believe. Les Bennington, National Pony Express Association president, is one who doubts young Cody actually rode for the Pony, but adds, “I cut him some slack, because even if he didn’t dispatch mail at that time, he later kept the vision and memory alive by featuring the Pony Express at all his Wild West shows.”

While the riders were the stars of the Pony Express, they had a strong supporting cast. William Finney, for one, was a pugnacious station agent posted in San Francisco who bulldogged reconstruction of the Pony Express line after the Pyramid Lake War (May–August 1860). Despite popular legend, James Butler Hickok, later known as the famous lawman and shootist “Wild Bill,” was never a rider. He was too big and far too old (he was 23 when the service began). Rather, Hickok was an assistant keeper at Rock Creek Station in southeastern Nebraska (near the present-day town of Endicott). It was there he got into an argument with former property owner David McCanles and two of his companions. The ensuing gunfight left McCanles and his associates dead and Hickok with a reputation as a fearless gunfighter.

Wranglers carefully selected the horses that carried the young riders. The mounts stood an average of 14½ hands (58 inches) high and weighed no more than 900 pounds. Though smaller and lighter than most horses, they were not, strictly speaking, “ponies.” In fact, they represented various breeds—Morgan, mustang, pinto, even thoroughbred. But all were specially chosen for their strength and endurance.

With riders and horses assembled, the service was left to equip them for the job. Riders carried the mail in a leather saddle cover called a mochila (Spanish for “knapsack”). Designed with a hole for placement over the saddle horn and a slit partially up the back, the mochila was held in place by the rider’s weight. Each mochila comprised four reinforced leather boxes, or cantinas, each secured with a small, heart-shaped brass padlock. The four cantinas could carry about 20 pounds of mail in all.

A rider’s standard gear also included a canteen, a Bible, a brace of revolvers (or one revolver and one rifle, depending upon the rider’s preference) and a small horn, or “boob,” used by the rider to alert a station keeper of his imminent arrival. The combined weight of the rider, mail and accoutrements came to about 175 pounds. The service eventually trimmed that weight by stripping riders of their additional weapons and Bibles.

The routes were demanding, making it imperative that men and horses maintain top physical condition—an expensive proposition. Conditions at home stations, while not luxurious, were quite comfortable, and the food was often very good. Some home stations acquired such good reputations for well-prepared meals that they drew customers from miles around, eager to share the riders’ fare. The horses, for their part, weren’t left to graze but given nutrient-rich feed shipped from Iowa farms to each station—again a very costly proposition.

As it turned out, the rates charged for Pony mail—as much as $5 per half-ounce—could not cover daily expenses. While this seems a self-defeating proposition, it may well be that Russell, Majors and Waddell simply saw it as a necessary expenditure in view of their other business ambitions. Given the positive press generated by the Pony Express and the potential new contracts that press might garner in their freighting and stagecoach services, the business trio probably saw the debt incurred as a very legitimate “sunk cost” investment on potential future return.

The early reputation of the service supports this view. Mail was delivered at record speed. Newspaper coverage was uniformly positive, even laudatory, and the exploits of the riders were celebrated in ubiquitous dime novels and magazine series. But circumstances, fate and fiscal realities were to play pivotal roles in the organization’s future. Delivery, while fast and remarkably reliable, was exceptionally costly for that time. Charging rates as high as $15 for delivery of a single item, the Pony Express, while attractive to the general public, was almost invariably a prerogative of the very well-off. Russell, Majors and Waddell soon found that their enterprise, for all its glamour and public acclaim, was hemorrhaging money.

Making matters worse for the firm was the unanticipated conflict with Northern Paiute Indians and their allies. When Nevada businessman J.O. Williams abducted two young Paiute women, reportedly for illicit purposes, local tribes were quick to react—particularly since the father of one was a prominent Paiute warrior. In a retaliatory strike on May 6, 1860, angry warriors raided the Williams establishment, which housed a saloon and general store and served as both a stagecoach and Pony Express station. The Paiutes set the way station afire, killed three of the workers (Williams was away at the time) and then unleashed their wrath on other nearby stations. To the Paiutes, the Pony Express and its stations were emblematic of the encroaching white man and thus legitimate targets.

The Pyramid Lake War was not especially costly in terms of lives—each side suffered fewer than 200 casualties, small potatoes for a nation engaged in Civil War. But the fighting and its aftermath devastated the Pony Express. The Paiute warriors destroyed numerous stations and killed 16 employees, including one rider. The company actually suspended delivery for three weeks, and when it initially resumed, service was considerably slower. At one point, riders dared not cross the conflict zone without an accompanying cavalry detachment, which in turn reduced their rate of travel to a mere 40 miles per day.

The costs to reestablish the line were staggering. When Russell, Majors and Waddell ran up the damages incurred by the Pyramid Lake War, the total was more than $75,000, much of that to rebuild way stations and stables and replace equipment. When one considers that the initial cost of establishing the entire network of stations was $100,000, the impact of this setback becomes much more stark. And the day-to-day maintenance of the line and services continued to add up. Over the course of its operation, the Pony Express cost its owners $30,000 per month, or $480,000 for its duration. Thus, their enterprise not only failed to make a profit, but also incurred a significant loss of more than $200,000.

Adding to the discomfiture of Russell, Majors and Waddell were economic and political factors over which the partners had absolutely no control. The government contract for expanded mail delivery they had hoped to land for their Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company fell apart, and the Butterfield Overland Stage began operations along the western division (from Salt Lake City to Sacramento) of the central route. In January 1861, Russell—his company bankrupt—signed over most of his holdings to his largest creditor, “Stagecoach King” Ben Holladay. In April 1861, Wells Fargo took over the Pony’s western leg and significantly reduced the cost of postage (which eventually fell as low as $1 a half-ounce). The Pony had become more affordable, but it was too little too late.

The outbreak of Civil War, contrary to expectations, also had a disruptive effect on government mail contracts. As the central Eastern seaboard devolved into a sprawling battlefield, affairs in the West took on diminished significance. The final nail in the coffin of the Pony Express was completion of the transcontinental telegraph at Salt Lake City on October 24, 1861. Two days later, the Pony Express ceased operations. The great experiment was over.

A major American enterprise had failed, but it was hardly the end of the world. Telegraphs were convenient, and stagecoaches kept the mail coming. And business boomed after the war as the country reunited and people sought new opportunities in the West. After completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869, mail was delivered at speeds that soon made the Pony Express seem quaint. But it also seemed romantic, even more so through the years, as trains, trucks and planes mechanized mail delivery. Today, the Pony stands out among other failed enterprises, remembered not for its flaws and ultimate failure but for its mythical resonance. For almost 19 months, a relatively small group of daring young men galloped across the plains, forded streams, outran hostile Indians, braved blizzards and clattered along mountain trails. In sum they covered more than 650,000 miles and carried 374,753 pieces of mail. And, as far as anyone can determine, only one or two mochilas of mail went missing. It is small wonder, then, that 150 years later we still celebrate the Pony Express, not for the business failure it was but for the ideal it represented—humans overcoming time, distance, terrain and the elements to deliver the mail.

Frederick J. Chiaventone, a former Army officer who taught guerrilla warfare and counterterrorist operations at the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College, is now an award-winning novelist, screenwriter and commentator. Suggested for further reading: Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express, by Christopher Corbett, and Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga, by Raymond W. Settle and Mary Lund Settle.