In the summer of 2014 the deaths of two black men in confrontations with police officers riveted the nation’s attention. In July Eric Garner, of Staten Island, N.Y., suffered a fatal heart attack while being arrested for selling loose cigarettes; officer Daniel Pantaleo had his arm around Garner’s neck as he was being subdued. Then in August Michael Brown, suspected of robbing a convenience store in Ferguson, Mo., was shot and killed by officer Darren Wilson after the two had an altercation. Protests followed both incidents, first locally, then nationwide, accusing police of systematically brutalizing poor black men. Brown’s alleged last words, “Don’t shoot!” became a slogan.

In late November the grand jury investigating Brown’s case decided not to indict Wilson; 10 days later, the grand jury investigating Garner’s decided not to indict Pantaleo. Protests became larger and louder, especially in New York City where nightly marches blocked streets, bridges and tunnels, and protestors held “die-ins” in public places like Times Square and Grand Central Terminal.

Then on December 20 Ismaaiyl Brinsley, a disturbed black man with a history of criminal violence, murdered two police officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, as they sat in their patrol car in Brooklyn. Brinsley had explained himself on Instagram before doing his deed: “I’m putting Wings on Pigs Today…They Take 1 of Ours…Lets Take 2 of Theirs.” (Brinsley killed himself as cops closed in on him.) The dead officers, said New York police commissioner Bill Bratton, “were, quite simply, assassinated—targeted because of their uniform.”

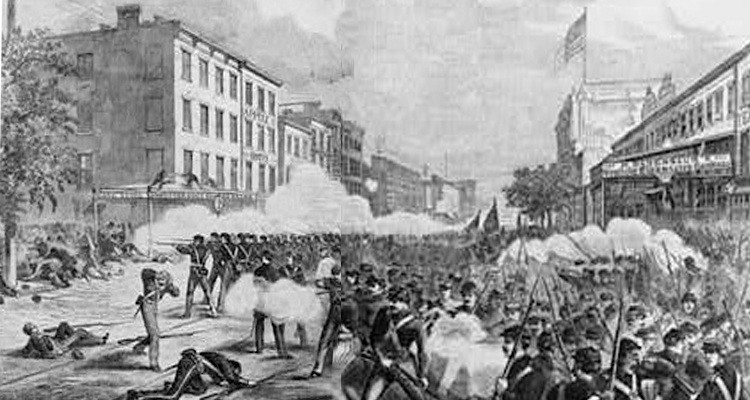

Police, minorities and the underclass have been tied in violent knots throughout American history. The ugliest episode by far was the New York City Draft Riot in July 1863. Then, however, the angry poor were Irish Americans, and they lashed out not only at the police and other authority figures but at equally poor black New Yorkers.

The fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861 and the start of the Civil War brought a surge of patriotism to New York, but it wore off as the casualties mounted. In 1862 Horatio Seymour, a Peace Democrat, won the governorship. The Enrollment Act, a draft law passed by the Republican-controlled Congress in the spring of 1863, soured New Yorkers further, for it was unfair as well as onerous. A draftee could escape service by engaging a substitute to fight in his place or by paying a lump sum of $300—alternatives far beyond the reach of the poor. At a rally in New York City on July 4 Governor Seymour all but invited popular resistance: The “doctrine of necessity,” he reminded his audience, “can be proclaimed by a mob as well as by a government.”

Mobs swung into action on July 13, the second day of the draft’s operation in New York. Names were drawn from a drum at Third Avenue and 47th Street, then a newly developed, out-of-the-way location, guarded by 60 policemen. As the drawing began, a company of angry volunteer firemen appeared; they chased away the cops and burned the drum. Rioters on both the east and west sides of town closed shops and factories, cut down telegraph poles and tore up train tracks. An armory at Second Avenue and 21st Street was stripped of its carbines, then burned.

Violence raged for four more days. There were three primary targets. The first was the police: It was open season on officers. John Kennedy, the police superintendent, was beaten to a pulp as he tried to make his way, on foot, to the site of the first outbreak at the draft drum. Other policemen were simply beaten to death. In a bad tactical decision, officers were sent out in small parties to smother discrete flare-ups, but they were frequently routed or overpowered.

A second class of targets was the symbols of the Republican Party. Even though New York was a Democratic town, there were many to choose from. Mobs gathered outside the offices of the New York Times and the New York Tribune, both Republican newspapers. The Times had procured Gatling guns to defend itself; rioters had better luck at the Tribune where they managed to break into the building and start a fire, but they were driven off by a group of policemen brought in from Brooklyn. The city’s financial center, then as now at Wall Street, was well protected; workers at the Customs House and the Sub-Treasury Building manned the windows, armed with bombs and bottles of vitriol.

Black New Yorkers, the riot’s third target, were helpless. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued at the beginning of the year, had made the Civil War formally a crusade against slavery; black people thus became, in the eyes of poor draftees, the cause of their woes. Rioters on the Lower West Side, where black New Yorkers then lived, attacked tenements and taverns screaming, “Kill all n——s!” At Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street the Colored Orphan Asylum was torched, the mob there shouting, “Burn the n——s’ nest!” The children, mercifully, managed to escape.

Contemporary writers left vivid if biased accounts. George Templeton Strong, a Republican lawyer and diarist, raged at the “Irish anti-conscription N—— -murdering mob…a jacquerie that must be put down by heroic doses of lead and steel.” Herman Melville composed a gloomy poem: “The town is taken by its rats. . . .And man rebounds whole eons back in nature.”

Fear and force brought the rioting under control. Governor Seymour, alarmed by the passions he had helped unleash, joined with Tammany Hall, the local pro-war Democratic organization, to appeal for calm. (Tammany would later establish a fund to pay the exemptions for poor draftees.) On July 15 Mayor George Opdyke telegraphed President Lincoln begging for troops. Since Robert E. Lee, retreating from Gettysburg, had put the Potomac between himself and George Meade, troops were available; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent five regiments to the beleaguered city. From the night of the 16th through the 17th, soldiers fought rioters with bayonets and howitzers. By the night of the 17th the violence had stopped. Ten thousand troops garrisoned the city, camping in Washington and Madison squares.

Most of the rioters had been poor Irish immigrants, as were many of the policemen who had tried to control them. Irish Americans managed to assuage their feelings of grievance and exclusion by swelling the ranks of Tammany Hall, eventually becoming the political establishment in New York (and in other cities as well). With few options for legal or political redress, blacks fared worse. After the Draft Riot the Republican Union League Club helped organize two black volunteer regiments for the U.S. Army, a chance for blacks to show their patriotism and pride. But when the nation began its long post-Reconstruction retreat from enforcing civil rights, blacks in the North as well as the South were reduced to second-class citizenship. Not until the mid-20th century would they carve out a handful of political bases scattered across the country.

The United States has seen many costly clashes between its citizens and the police—53 people died in the Los Angeles riot of 1992, and mid-’60s riots in Detroit, Watts and Newark claimed 43, 34 and 26 lives, respectively—but the Draft Riot was the worst. The official death toll was 119, though contemporaneous estimates went as high as 1,000.

The police try to uphold justice, though sometimes they commit injustice. When that happens, it is generally the poor, especially poor minority groups, that bear the brunt. Police misconduct and political disenfranchisement can be curtailed. Meanwhile, Americans should remember what gross unfairness and primal rage looked like.