Louisiana units played a key role during the Vicksburg campaign

The area surrounding Pollard, Ala., located east of Mobile, in the early months of 1863 was overrun with deserters and stragglers from both armies who had flocked to this sparsely populated and isolated locale. Fortunately for the local populace, which included a large number of civilian refugees from Pensacola, Fla., several Confederate units were stationed nearby to protect them if required.

The command consisted mainly of Alabama and Florida units and the 19th Louisiana Infantry. Private George Asbury Bruton of the 19th Louisiana wrote to his sister and described Pollard: “This is the poorest country I ever saw in my life or ever expect to see. Tell Ma I am sorry that I can’t say any thing in favor of her old native state but we are camped in the out-edge close to no where. I never saw a goffer [gopher] before I come to this country & I imagin that is all this country is fit for is to rais goffers.”

Despite Bruton’s low opinion of his surroundings, these forces served another vital purpose in their assignment to keep an eye on the Yankees at Pensacola; thus, the assembled Confederates units were officially deemed an “army of observation.”

The Louisianans were added to this garrison in part to recoup their strength after appalling losses at the Battle of Shiloh, where they earned the sobriquet “Bloody 19th.” In addition to their daily drudge of drill and outpost duties, music was incorporated into the 19th with both practical and spiritual results. The 19th’s commander, Colonel Wesley Parker Winans, was a “lover of music” and formed a regimental band. Douglas John Cater, a transfer from the 3rd Texas Cavalry, was tabbed as drum major who oversaw four other drummers.

Cater also implemented a string band that further raised the spirits of the soldiers. The regiment took up money that was used to purchase musical instruments from Mobile. “We secured,” Cater later recalled, “a good violin [for Cater’s brother, Rufus], a guitar [for John W. Bonham who also sang lead for the melodious quartet], a base violin [for Lieutenant Frank Smith] and a piccolo [for himself].” Cater’s orchestra was soon serenading young ladies throughout the countryside.

Preparation for resumption of duty at the front lines soon marred the serenity of the concerts. Orders came to pack up and get ready to move by train starting April 8 and ending May 31 at Jackson, Miss. During the same time, the 5th Company of Washington (Louisiana) Artillery was passing through Mobile from Wartrace, Tenn. The last time the 19th Louisiana and the Washington Artillery served side by side was at Shiloh, where both units were part of a makeshift brigade with the Crescent Infantry, 24th Louisiana, during the battle’s second day. The two units, along with the Crescents, bonded from the fighting they endured.

The brigade the 19th and Washington Artillery joined consisted of the 32nd Alabama Infantry, 13th and 20th Louisiana Consolidated Infantry, 14th Louisiana Sharpshooter Battalion, and 16th and 25th Louisiana Consolidated Infantry, all under the command of Brig. Gen. Daniel W. Adams. The soldiers learned they were ordered there by General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, who was assembling an army for the relief of the Vicksburg garrison, besieged by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Johnston arrived in Jackson a couple of weeks before the Louisianans and immediately began to formulate a plan to free up the forces inside of beleaguered Vicksburg.

Confederate Secretary of War James Alexander Seddon had dispatched Johnston to Mississippi on May 9 with orders to take “chief command of the forces, giving to those in the field, as far as practicable, the encouragement and benefit of your personal direction.” Grant’s men, however, were already positioned between Johnston and Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton’s forces just east of Vicksburg. Some of Pemberton’s soldiers attempted to join Johnston, but they were soundly defeated at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, and retreated back to their breastworks. Thwarted at rescuing Pemberton, Johnston resolved to attack the Federal rearguard and trap them between the two Southern forces, and he waited for reinforcements to arrive at Jackson.

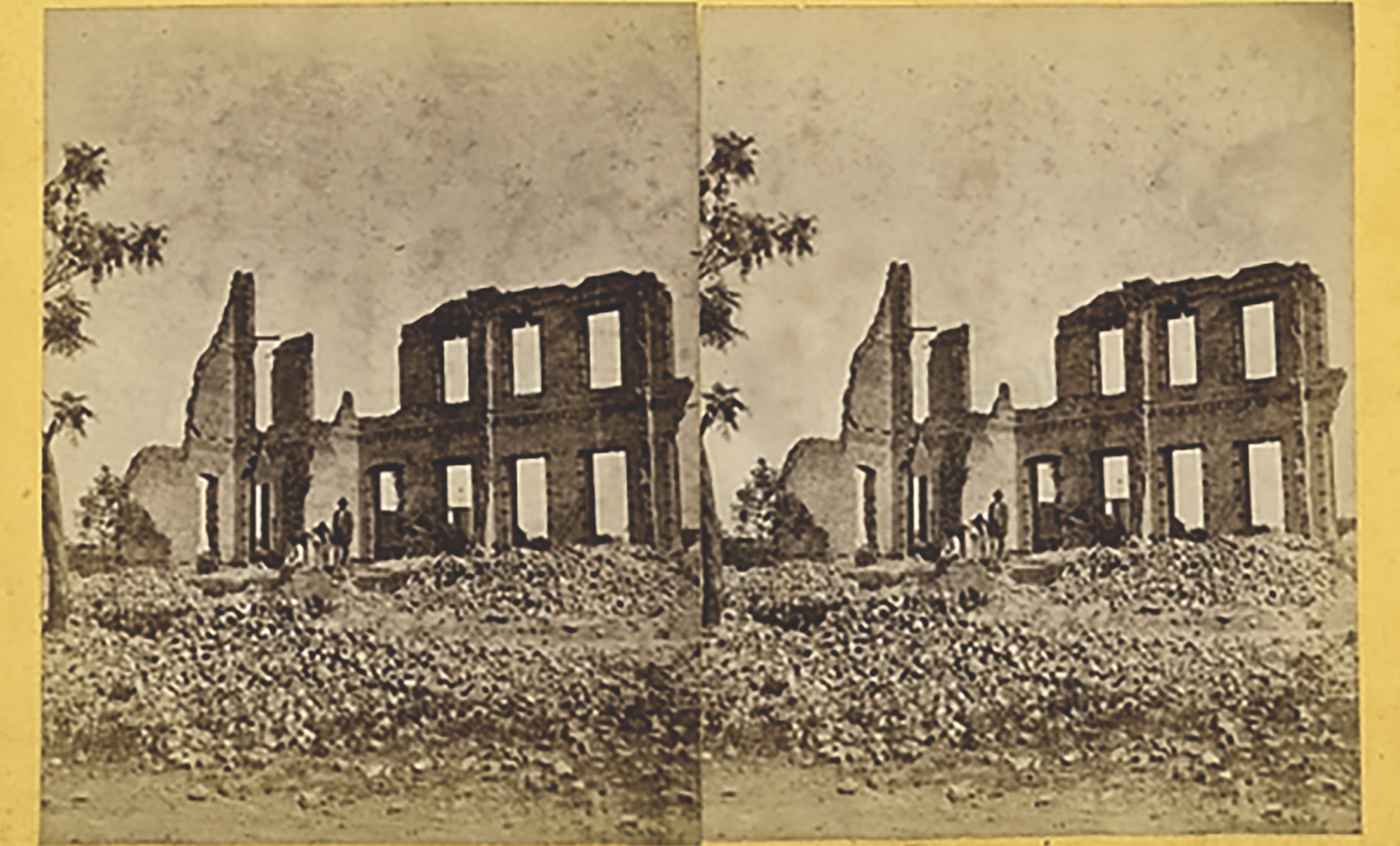

When the 19th arrived, much of Jackson was in shambles. In mid-May, in an attempt to destroy facilities housing Confederate war materials, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s troops started fires to burn every building in the city capable of producing war material. Both public and private residences went up in flames despite one of the “most drenching rain storms” the night prior to the city’s brief occupation by Federal units. The residents later dubbed their city “Chimneyville” because chimneys were the only thing left of many of the burned buildings. Private Rufus Eddins of the 19th observed upon his entrance to the city, “The Yanks nearly ruined Jackson…they burned up $15,000,000 worth of property.”

Shortly after pitching their tents in a valley about 200 yards from the Mississippi capitol building, Cater recalled the 19th Louisiana was ordered to go on provost duty three miles from town. Eddins complained he was “standing guard ev[e]ry other day.”

Aside from guard duty, members of the Washington Artillery spent time ensuring the unit was well equipped. Captain Cuthbert H. Slocomb managed to secure new issues of clothing, refurbished wagons, “camp equipage, artificers tools, etc.,” and his battery was better equipped than it had been in over a year’s time.

Rumors about Vicksburg began trickling in. As the middle of June approached, Eddins wrote, “[T]here is talk ev[e]ry day of Johonsons [Johnston’s] mooving on the Yanks. [T]hey have Vicksburg in a clost [closed] place. [T]hey are within rifel shot of our works and as well fortied [fortified] as we are in some places. The Pontoon Bridges from here this morning. I expect there will be a forward move shortly. I expect our Regt will be left here to guard Jackson.” Despite the rest and refitting, Eddins was experiencing the doldrums when he explained, “I don’t feel like writing humor this morning.” Soon, others in the 19th Louisiana would have a cure for his sagging spirits.

Because of his appreciation of music, Winans ordered the 19th Louisiana’s string band instruments safely stored among the baggage of the regiment on their winding travels from Pollard to Jackson. Cater and the other members of the musical group excitedly hauled them out and put them to use. One night, the group somehow secured the use of an ambulance to transport them, along with Adjutant A. Ben Broughton, Captain Jack Hodges, and Sergeant Thomas J. Prude, a few miles outside of town with the purpose of serenading some young ladies.

It was a beautiful moonlit night; the men brought out their pieces and took note of their surroundings, bedecked with a plethora of decorative flowers and shrubs. “[T]he folding doors were thrown open by an affable old gentleman, who welcomed us and invited us” inside, so impressed was he with the band’s selection of tunes. In the dining room, the bandsmen were delighted to discover a “sumptuous repast” awaiting them. Cater later remembered his brother Rufus saying the dessert cake “was too pretty to cut.” Wines, salads, and much more awaited the talented musicians, all surrounding a notable vase inscribed, “Vicksburg, Vicksburg, Vicksburg.” Discreetly tucked inside the flower arrangements encircling the vase were dainty notes thanking the soldiers “for the serenade and conveying happy wishes.”

While the men under his command were involved in frivolous activities to pass the time, Johnston realized he was not getting any more additions to his small “Army of Relief.” He even debated with Confederate President Jefferson Davis concerning the actual number of men he had on hand. The general speculated he had in the neighborhood of 23,000 soldiers fit for duty while the president countered with an amount totaling 34,000 troops. Other governmental officials in Richmond chimed in and confirmed the president’s mathematics, but Johnston insisted those numbers were blown out of proportion. Finally, Johnston was told by Confederate Secretary of War Seddon in no uncertain terms, “You must rely upon what you have and the irregular forces in Mississippi.” Aware of Johnston’s probable approach, Grant instructed his command to build another set of entrenchments that would protect the Federals from an offensive emanating from Jackson.

During most of late June, soldiers in Jackson could hear cannonading originating from the direction of Vicksburg. On the first day of July, Johnston finally headed toward Vicksburg with his army. Cater noted he and his comrades marched all day and reached the outskirts of Clinton more than a dozen miles away. A Kentuckian remembered it was, “The hotest march we have ever made. Many soldiers tumbled down the road from sun-stroke.”

To combat the extreme heat, the officers elected to take up the next day’s march before daylight. An Alabamian remarked, “Orders issued to allow no music from bands, beating of drums nor any noise above ordinary tone of conversation,” a hardship for the musically inclined Louisiana troops. Private Eddins remembered that “A grate many fell, some stretch on the side of the road.” Late in the afternoon, Johnston’s exhausted soldiers halted and stretched out to sleep alongside the road.

The Army of Relief stayed in a holding pattern for most of July 3 and 4. One disgruntled Alabama soldier complained, “Our idea of generalship was that if our expedition was intended for a relief of Vicksburg, it should be a bold and quick movement. It was irritating to be dallying along at the rate we were going, but we had implicit confidence in General Johnston and hoped all would turn out well.”

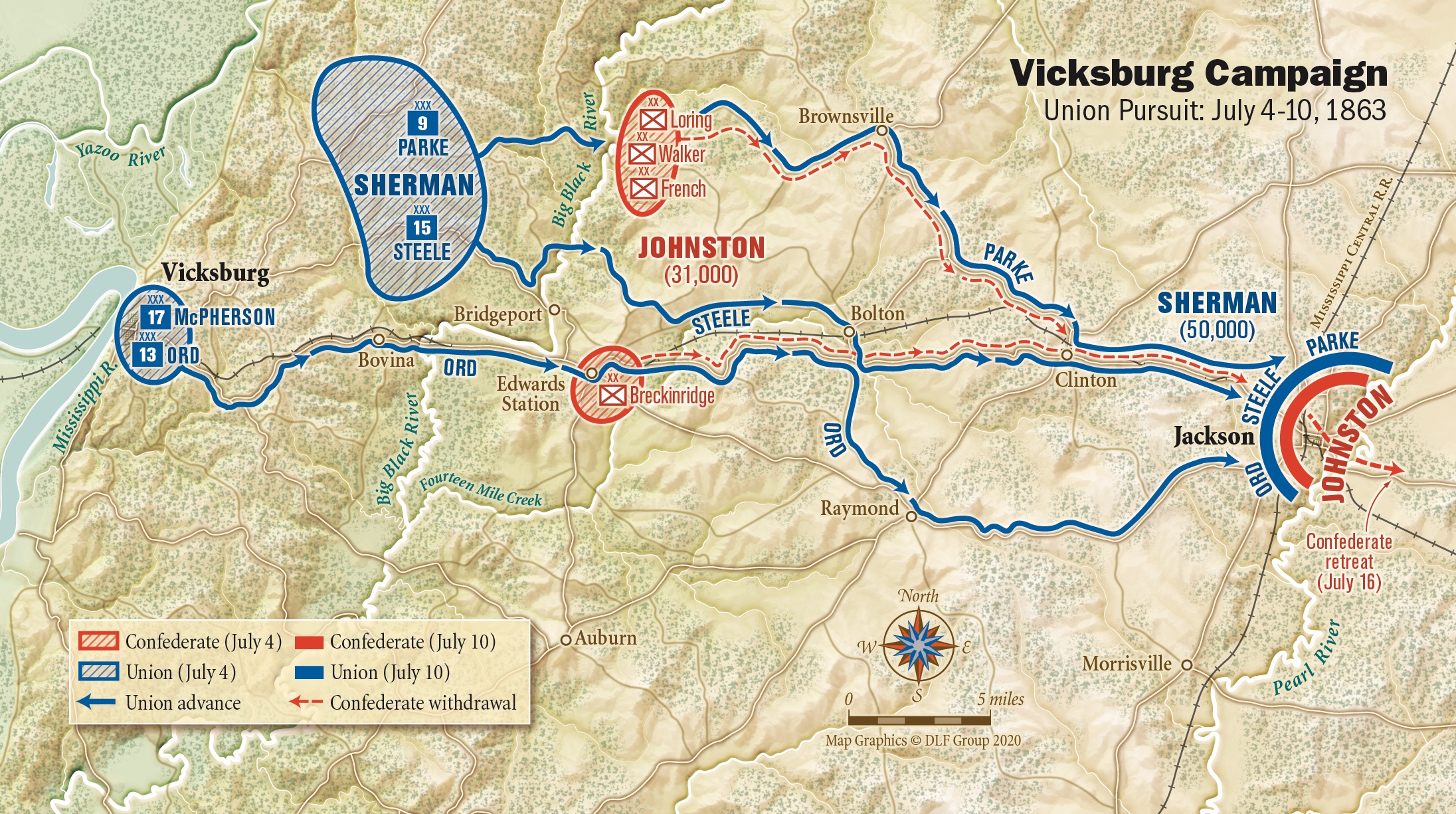

Meanwhile, after negotiations on July 3, Grant prepared to accept the surrender of Vicksburg’s garrison, thus ending the long siege. Soon thereafter Grant instructed Sherman: “I want Johnston broken up as effectually as possible, and the [rail]roads destroyed.” Sherman responded, “[T]elegraph me the moment you have Vicksburg in possession, and I will secure all the crossings of [Big] Black River, and move on Jackson or Canton, as you may advise.” As an Illinois foot soldier put it on July 5, “We were called out and started on the march toward [Big] Black River at an early hour. We were marched at a very rapid pace as Gen Sherman was trying to steal a march on Gen Johnston before he learned of the fall of Vicksburg.”

On the afternoon of July 5, Johnston’s command assembled and advanced about six miles toward Vicksburg. One Louisiana soldier commented, “The weather is very dry and the roads a foot deep in dust.” An enlisted man serving in the Breckinridge’s Division proclaimed it “the hardest marching ever” and noted when his unit halted for the evening, they “bivouacked in line of battle on the battle field of ‘Champion’s Hill.’”

The next day was ominous for the Confederates as word began to spread throughout Johnston’s forces of Vicksburg’s fall. Cater recalled, “Gloom is on every countenance, with Pemberton’s army prisoners in the hands of Gen. Grant and the war prolonged.” Johnston’s army reversed their course towards Vicksburg and headed back to Jackson. Continuous forced marching caused elements of Johnston’s men to arrive back in Jackson toward the late evening amid a “heavy rain & storm.” Eddins wrote, “We got back the night of the sixth. [T]he last day we marched nearly all day and a good portion of the night.” During the trip, the Washington Artillery stopped on a regular basis to deploy into battery to confront any perceived rearguard attacks. Eddins wrote, “[W]e arrived in Jackson [and then] we were ordered to the ditches.”

The units settled into the trenches in an arc configuration with both flanks resting on the Pearl River per Johnston’s orders. The Louisiana brigade manned the extreme right side of the Confederate line’s left flank, straddling the New Orleans Railroad. In line from the left were the 16th and 25th Consolidated Louisiana; 32nd Alabama; 5th Company, Washington Artillery; 19th Louisiana; and 13th and 20th Consolidated Louisiana. The 14th Louisiana Battalion was stationed nearby with its dependable sharpshooters. Incredulously, the members of the Washington decried the use of a barricade for protection as they were used to fighting out in the open. First Lieutenant J. Adolphe Chalaron explained, most “had never handled anything heavier than a pen,” and this experience became “their first initiation handling picks and shovels.”

Slocomb’s gunners were not the only soldiers in the area unfamiliar with digging implements. Men of Breckinridge’s Division scoured the city in search of “negroes to work on the fortifications.” One group managed to corral quite a crowd, “among them a few dandy barbers, who did not fancy wielding the pick and shoving the spade much.” One of the Kentucky natives remembered, “We layed around & took it easy while the negroes used the picks, spades & axes.” The Army of Relief’s commander personally inspected the earthworks and found them “miserably located and not half completed.”

Johnston ordered 4,000 bales of cotton to help augment his defenses. Of Johnston’s directions, a Georgian surmised, “I think he is going to make a stand here. He is going to fight the Yanks as old Jackson did the English at New Orleans, behind the cotton bags.” Slocomb “erected a strong traverse of cotton bales” around the battery and proclaimed, “Thus we formed quite a comfortable redoubt for ourselves.” This area of fortifications was referred to as Fort Breckinridge in honor of their division commander. Second Sergeant James Elijah Carraway of the 19th Louisiana wrote, “[A]ll of the timber and underbrush had been cut down for one quarter of a mile in front of our works.”

“A very fine but abandoned brick residence stood out in front of our works” that belonged to William A. Cooper’s family, recalled Carraway. One of Slocomb’s gun crew confirmed his statement by remarking, “[It was indeed a] splendid mansion…which had been deserted by the family, leaving most of the household effects behind.” On the 10th, Cater volunteered to join a party of five from Adams’s brigade and sharpshoot from near the home. “I volunteered to go and a musket and cartridges were furnished me,” Cater later speculated, “There was a large cistern under a dwelling in the yard. The water was cool and it seemed the Federals knew that the cistern of good water was there and they wanted it.” Of the Yankees, he noted, “Their guns were better than ours and they were doing good execution while our guns could not reach them, only raise the dust twenty or thirty feet in front of them.” Not long after the Southerners settled in, one of them was hit by an enemy bullet. Two men were required to drag him to safety, leaving Cater and another man to scramble behind a tree until they could retreat under the cover of darkness. Cater resolved to not volunteer for sharpshooting again “if I could not get a longer ranging gun.”

This detachment was firing into the distant ranks of Union Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord’s 13th Corps. Their attention toward the Cooper house caused Johnston to direct it to be burned immediately. A small group comprised of Louisianans was tasked with the job. Cater grabbed a “little piece of broken mirror and about a yard of Brussells carpet for use in camp.” Carraway pocketed a piece of one of the “large and costly mirrors” so he could “afterwards behold his own half-starved features and ragged clothes,” and he also cut himself a blanket-sized section of the carpet. All the men appropriated a suitable volume from the splendid library.

The squad came across a magnificent piano and a “swarthy Creole” from the Washington Artillery “proposed that it be turned over to his battery as most of them were musicians, all of them French.” It was agreed upon, and the men picked up the heavy piano and carried it back to their breastworks in the dead of night. The large musical instrument was safely placed among the large cotton bales. After they were gone, the remaining men, much to their chagrin, began to “apply the torch” to the magnificent home.

Bolstered by the reinforcements from the timely arrival of Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair Jr.’s division of the 15th Corps, Ord’s men made a heavy reconnaissance toward the cistern at the Cooper residence the next day but were met with the deadly fire of one of Slocomb’s rifled cannons sent out 500 yards in advance of Fort Breckinridge to hamper the Federal advance. After being bloodied heavily, the Northern troops retired to a safe distance. With the onset of evening, the Union troops were treated to a concert of melodies played by the Southerners on the piano and accompanied by hundreds of Louisiana soldiers singing such patriotic songs as Dixie.

An hour before noon on July 12, elements of the 13th Corps began to attack the well-defended Confederates, despite orders not to bring on a general engagement by their superiors. As the Union advance developed, Lawrence Pugh of the Washington Artillery made his way to the piano and began playing it enthusiastically. Fellow cannoneer Andy Swain soon pushed him aside, grabbed an ammunition box, flipped it over, and took a turn at the ivory keys. Other men packed around the piano and sang along with the songs.

The force moving on Fort Breckinridge consisted of two divisions from Ord’s 13th Corps. He instructed them to “make a reconnaissance, and, if it is necessary to form a line and attack to drive the force in front, do so, so as to keep your connection with the main corps.” The Federals dispatched the 5th Ohio Independent Battery to shell the Confederates in the vicinity of Slocomb’s battery and Winans’ infantry. The Washington Artillery coolly responded to the attack but with only two of their cannon, thus not revealing their remaining arsenal. One of the Yankee brigade commanders hesitated upon receiving the Louisianans’ return fire. Ordered to continue forward, Union Colonel Isaac Pugh complied and moved to a cornfield in front of the fort. The other division halted forward progress and dug in while Pugh’s men advanced amid a hail of cannon and small arms fire from Slocomb’s and Winans’ men. Felled trees blocked their progress as a Kentucky artillery unit and the 32nd Alabama managed to get an angle on them to multiply the murderous firing.

As Pugh’s men trudged forward, some of the 19th Louisiana “had told the battery ‘boys’ to send for me,” described Cater, “and that I would give them some good music on that piano.” Cater responded to Slocomb’s call, along with his brother Rufus. As the Southerners enjoyed Cater’s playing while the shells and bullets whizzed by, Slocomb caught sound of a Federal movement and “saw them coming at a charge.” The Cater brothers quickly scurried back to their post. Winans’ regiment held their fire until Slocomb’s cannon belched forth a volley in unison. Cater reported the deadly rounds took a toll of 260 men dead in their front, 150 prisoners, and 160 wounded. One of the Washington Artillery recounted years later, “’Tis over; with a rush the piano is sought again. Not twenty minutes has sped since its last notes have died away.” When Pugh’s regiments streamed to the rear, Winans’ soldiers emerged from behind the breastworks to collect their spoils of war.

The July 12 attack was the only major assault on Jackson, and by the 17th Johnston’s forces abandoned the city. One of Breckinridge’s Kentuckians recalled, “About midnight…we folded our tents like the Arabs and quietly stole away.” The Confederates burned the bridge they retreated across and moved to Morton, a short distance away. Looting and destruction by the Federal soldiers entering Jackson was rampant until Blair’s division arrived to restore order.

Into the next century, Carraway would sit at a local store and relate the story of the piano in the trenches to anyone who would listen. Used as a horse trough by the Yankees after they retook the city, the piano found its way to New Orleans after the war where it remains on display today at the Confederate Memorial Hall Museum. It is a fitting honor for the musical instrument that unintentionally played the swan song of Johnston’s Army of Relief.

Richard H. Holloway works for the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism and is president of the Civil War Round Table of Central Louisiana. His biographies of Hamilton Bee, William Boggs, and Richard Taylor appeared in Confederate Generals of the Trans-Mississippi, Vol. 3 (University of Tennessee Press, 2019). This article is adapted from his essay in Vicksburg Besieged (SIU Press, 2020), edited by Steven E. Woodworth and Charles D. Grear.