Survival in an Alabama Slammer:

Inmates at the Confederacy’s Cahaba Federal Prison had little more food and a lot less space than prisoners at Andersonville, but their mortality rate was considerably lower—thanks to one man’s humanity.

On the afternoon of May 11, 1883, Hannah Simpson Grant died quietly in her home in Jersey City, N.J. Her son, Ulysses S. Grant, arrived later that day. To her pastor, the Rev. Dr. Howard A.M. Henderson, Grant entrusted arrangements for the funeral. Grant wanted no mention made of his own success. He asked Henderson simply to eulogize Hannah Grant as a “pure-minded, simple-hearted, earnest Methodist Christian.”

On the afternoon of May 11, 1883, Hannah Simpson Grant died quietly in her home in Jersey City, N.J. Her son, Ulysses S. Grant, arrived later that day. To her pastor, the Rev. Dr. Howard A.M. Henderson, Grant entrusted arrangements for the funeral. Grant wanted no mention made of his own success. He asked Henderson simply to eulogize Hannah Grant as a “pure-minded, simple-hearted, earnest Methodist Christian.”

The man in whom General Grant placed so much trust had served honorably during the Civil War—but on the side of the Confederacy, and as the commandant of a prison camp.

Soldiers in both armies despised Civil War prisons as places of hunger, harsh treatment and deadly diseases, and for the most part they excoriated prison commanders as cruel and cold-hearted. But Henderson was an exception. Gentle and genuinely concerned with the welfare of inmates, Henderson achieved with resources nearly as limited as those at Andersonville, Ga., something the commandant of that prison, Henry Wirz, couldn’t: He kept his inmates alive.

Under Wirz’s regime, nearly a third of the 41,000 prisoners at Andersonville perished. At Cahaba, the mortality rate was 3 percent. According to Federal figures, only 147 of the 5,000 inmates died. The average mortality rate in Confederate prisons was 15.5 percent; in Union prisons, 12 percent.

There was little in the appearance of Cahaba, or in the conditions beyond Henderson’s capacity to control—overcrowding, rats, lice and sometimes meager food—to suggest to new inmates their fate would be any different than that of their less fortunate countrymen at Andersonville.

But Henderson’s humanity gave them hope.

Wisconsin cavalryman Melvin Grigsby entered Cahaba in the spring of 1864. His first stop was a room near the entrance. There Captain Henderson ordered him to surrender all his valuables, promising to keep a list and return everything “at the proper time.” Grigsby was skeptical; surrendered possessions had a way of disappearing in prisons. But when Grigsby and several hundred other prisoners were transferred to Andersonville, Henderson not only returned all the prisoners’ valuables, but also expressed his “sorrow and shame for the horrors of that shameful place.”

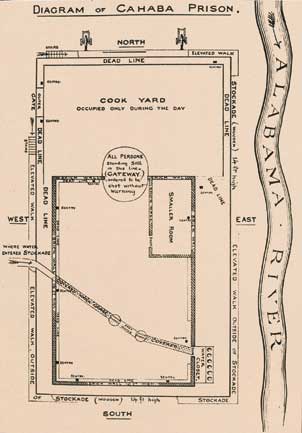

The Confederates established Cahaba Federal Prison in May or June 1863 in an unfinished red-brick warehouse on the west bank of the Alabama River in Cahaba, Ala., the seat of Dallas County. The town owed its name to the Cahaba River, which looped around the northern side of the town before emptying into the Alabama. The prison’s informal name was Castle Morgan, after famed Confederate cavalryman Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. The brick walls of the warehouse stood 14 feet high and enclosed 15,000 square feet. An unfinished roof left 1,600 square feet in the center exposed to the elements.

Under the roofed portion of the warehouse, Confederate prison authorities built 250 bunks of rough timber, one atop the other. Around the warehouse they raised a 12-foot wooden stockade with a plank walkway at the top for the guards. At the southeast corner of the stockade they built a four-seat privy. Drinking water for the prisoners came from an artesian well emptied into an open gutter, which flowed 200 yards through town before entering the stockade.

In July 1863, Henderson became commandant of Cahaba. A month later he also was named an agent for the exchange of prisoners, a duty that often took him away from the prison.

Henderson understood Northerners. He had graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University and studied law at the Cincinnati Law School. Preferring the church to law, he became a Methodist minister after graduation. Henderson was determined to run Cahaba with as much compassion as discipline and good order permitted, but the prison nonetheless had its share of problems.

Henderson understood Northerners. He had graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University and studied law at the Cincinnati Law School. Preferring the church to law, he became a Methodist minister after graduation. Henderson was determined to run Cahaba with as much compassion as discipline and good order permitted, but the prison nonetheless had its share of problems.

Quarters were cramped. In March 1864, there were 660 prisoners at Cahaba, a third of whom had to sleep on the dirt floor of the warehouse for lack of bunks. The polluted water supply posed a grave health threat. Prison surgeon R.H. Whitfield told the Confederate medical department that, in its course from the artesian well to the warehouse, the water “has been subjected to the washings of the hands, feet, faces, and heads of soldiers, citizens, and negroes, buckets, tubs, and spittoons of groceries, offices, and hospital, hogs, dogs, cows, and filth of all kinds from the streets and other sources.”

In response to Whitfield’s complaint, the quartermasters installed pipes to replace the open ditch, which gave the prisoners clean water to drink. But in the summer of 1864, General Grant ordered a halt in prison exchanges, and the population of Cahaba grew to 2,151 in October. Conditions deteriorated sharply. Cahaba became the most overcrowded prison, North or South. Each prisoner had only 7.5 square feet to call his own; those at incarcerated Andersonville had 35 square feet of space per man.

Rations dropped severely both in quantity and quality. The average daily issue became 12 ounces of corn meal, ground together with cobs and husks, 8 ounces of often rancid beef or bacon, and occasionally some bug-infested peas. Prisoners were not starved at Cahaba, but they were hungry enough that a gnawing desire for food permeated their dreams. “The same experience was often repeated,” remembered Sergeant Jesse Hawes of the 9th Illinois Cavalry. “Go to the bed of sand at 9:00 p.m., dream of food till 1:00 or 2:00 a.m., awake, go to the water barrel, drink, and return to sleep again if the rats would permit sleep.”

The number of rats at Cahaba grew at about the same rate as the prison population until, Hawes said, they became a veritable plague. They burrowed into every corner of the warehouse and swarmed through the prison yard. “At first they made me nervous, lest they should do me serious injury before I should awake; but after several nights’ experience that feeling was supplanted by one of irritation—irritation that they should keep waking me up so many times during the night, an annoyance that at length became nearly unendurable.”

But rats were a minor annoyance when measured against the infestation of lice, from which no prisoner was free. Private Perry Summerfield said that after his first night at Cahaba he was so covered with lice that his clothes “looked more like pepper and salt than blue.” Lice “crawled upon our clothing by day, crawled over our bodies, into the ears, even into the nostrils and mouths by night,” Hawes said.

Hardest to bear were the human vermin that infested the prison. The most pernicious came from among the prisoners themselves. Called “muggers,” they were a well-organized group of robbers for whom newcomers were the targets of choice. The muggers would beat a man senseless or render him defenseless with a rag of chloroform (obtained from guards in exchange for part of the muggers’ profits), and then strip him bare of money, watch, jewelry and keepsakes that the prisoner had managed to secrete from prison authorities.

It took a giant of a man named Richard Pierce to bring order. Standing nearly 7 feet tall, with chest and shoulders “enormous for a man of his gigantic dimensions,” the young private from the 3rd Tennessee Union Cavalry was so mild-mannered that his fellow inmates regarded him as an overgrown boy—until four muggers robbed his best friend. “Big Tennessee,” as the prisoners called Pierce, tracked down the robbers and knocked all four of them senseless. Big Tennessee’s two-fisted justice rallied the prisoners and cowed the muggers, the worst of whom joined the Confederates to escape retribution from their former victims.

There ironically was less human vermin among the guard force of 179 poorly trained conscripts. Most of the Confederates were humane and well-intentioned, but at least two stood out as cold-blooded murderers. One named Hawkins shot three men in one week from the walkway atop the stockade wall, recalled several former prisoners, “without the least shadow of reason or excuse for the murders.”

Another assassin, a boy not more than 16 whom the prisoners dubbed “Little Charley,” killed three prisoners. He shot two men at close range and bayoneted a third in the cooking yard, again for no apparent reason. One day Little Charley failed to appear on duty as expected, and among the prisoners the rumor arose that he had been granted a furlough for his “zeal as a guard.” Hawes decided to find out for himself. “Was he given a furlough because he killed so many prisoners?” Hawes asked a friendly guard. “I guess so,” drawled the Southerner, “that’s what we ’uns allers heerd.”

That murder would be condoned, much less rewarded, under Henderson’s regime was unthinkable. But on July 28, 1864, a new officer had arrived to command the military post of Cahaba and the prison guards. He was Lt. Col. Samuel Jones, a cruel man who had been twice captured and paroled, and then passed over for command of his regiment. Jones came to Cahaba with the professed intention of seeing the “God-damned Yankees” suffer.

The commander of military prisons in Alabama and Georgia, Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, complained to Richmond that he had not requested, nor did he want, Jones at Cahaba. The inspector general’s office opposed divided authority at prison camps and sided with Winder. They looked into Jones’ records and found no orders assigning him to Cahaba, but he nonetheless remained at the prison. Henderson’s duty as exchange agent took him away from Cahaba frequently. In his absence, Jones was in charge.

Jones instituted a unique form of punishment and applied it for violations of serious prison regulations. On a ladder resting against the outer wall of the stockade, Jones forced prisoners to grasp a rung just high enough so that their feet barely touched the ground, and then sustain their weight by their hands for a prescribed number of minutes. There certainly were worse forms of punishment in Civil War prisons, many of which were inflicted with less cause, but to men accustomed to Henderson’s moderate discipline, Jones’ methods seemed barbaric.

Amanda Gardner, whose home stood just outside Cahaba Prison, also found Jones’ behavior reprehensible. Gardner was a “thorough Rebel” who already had lost a son in the war and believed in the righteousness of the Southern cause, said one prisoner, but she abhorred brutality. When she demanded Jones cease punishing prisoners near her doorstep, the colonel rebuked her. “Your sympathy for the damned Yankees is odious to me,” Jones told her. “Now bear yourself with the utmost care in the future or you shall be an exile.” But Henderson intervened and endorsed all Gardner had done. After that, Jones left her alone.

Gardner did far more for the prisoners than protest cruel punishment. Soon after the prison opened she began sending gifts of food, which her young daughter Belle slipped through cracks in the stockade wall with the connivance of friendly guards. When winter came, she took up every carpet in her house and cut them into blankets in order to “relieve the suffering of those poor prisoners.” Gardner lent the prisoners books from a large and varied collection that an uncle had left her. Prisoners had only to send a note by a guard to Amanda or Belle in order to borrow a book from the Gardner library.

The good effect Gardner’s books had in alleviating tedium, which could sap a man’s will to live, contributed to the low death rate at Cahaba. Relatively good sanitation also played a role. After Whitfield’s report, water entered the camp in pipes rather than an open gutter. The water closet at the southeast corner of the stockade prevented human waste from contaminating the water supply.

The final factor favoring survival was the prison hospital, located in a rambling, two-story hotel called Bell Tavern that the Confederacy commandeered to serve both guards and prisoners. There were never quite enough cots to go around, but chief surgeon Louis Profilet and prison surgeon Whitfield treated Confederates and Northerners with equal consideration. Medicine was seldom in short supply. Men died in the Bell Tavern hospital, but not for want of care.

Neither did they die for want of effort by Henderson. In September 1864, Henderson, now a colonel, proposed a special exchange of 350 of Cahaba’s inmates. The Union district commander, Maj. Gen. Cadwallader C. Washburn, forwarded the request to the commissary general of prisoners along with a favorable comment on Henderson’s management of Cahaba.

The proposal made its way to Grant, who denied it as part of his larger policy of prohibiting prisoner exchanges. As winter neared, Henderson suggested the Federals send a ship up the Alabama River under a flag of truce and deliver supplies to the prisoners. Henderson and Washburn overcame the reservations of their superior officers, and in December a Union steamboat offloaded at Cahaba 2,000 complete uniforms, 4,000 pairs of socks, 1,500 blankets, medicine, writing papers and envelopes, and a hundred mess tins.

Henderson had done his best. But the prisoners wanted food more than supplies, and most bartered their new clothing to guards for extra rations. When the food was gone, wrote Henderson sadly, the prisoners were left with the same “scanty clothing and ragged blankets in a climate particularly severe in winter.”

In December, Cahaba was cursed with the arrival of a prisoner who nearly cost several dozen innocent men their lives. He was Captain Hiram S. Hanchett of the 16th Illinois Cavalry. Moments before Confederate cavalrymen captured him near Nashville, Hanchett had shed his uniform and donned civilian clothing, on the mistaken assumption that the Rebels would let civilians go. Hanchett further incriminated himself by adopting an alias. As he marched into Cahaba, Hanchett knew that he had made himself subject to conviction and execution as a spy.

To save himself, Hanchett concocted an absurd escape plan. He told a handful of prisoners his true identity and offered to lead them to the Confederate arsenal at Selma to steal weapons, and then another 125 miles to Federal lines at Pensacola, Fla. In the early morning hours of January 20, 1865, Hanchett and his co-conspirators overpowered the nine guards on duty and shoved them into the water closet.

Hanchett’s band never made it beyond the gate. The corporal of the relief saw the scuffle and called for help. Hanchett yelled into the warehouse for 100 “men of courage” to join him in rushing the gate. No one responded. Jones entered the prison with cannons and 100 guards, threatening to blow Hanchett and his men “from hell to breakfast.”

One of his coterie let slip that Hanchett was a Union officer, and Henderson wrote to the War Department for permission to court-martial him as a spy. His letter got lost in the crumbling bureaucracy of the dying Confederacy.

Henderson left Cahaba permanently in January 1865 for Union-held Vicksburg, there to dedicate himself to duties as agent for prisoner exchanges.

No sooner had Henderson left than a natural disaster of the first order confronted Jones. Late February downpours pounded the prison and surrounding country, and on March 1 the Cahaba River roared over its banks. A torrent of water swept through town and into the stockade. The water closet backed up, and by nightfall the prisoners found themselves waist-deep in fetid water.

The next morning a delegation of sergeants appealed to Jones to let the prisoners move to higher ground just outside the stockade. Jones refused for fear they might escape. As a dumbfounded Hawes recalled, “The possibility of an escape at that time was an absurdity. The whole country was flooded.” Sixty Confederate guards signed a petition on behalf of the prisoners. But Jones stood fast, and the prisoners stood shivering in the water for three days before Jones relented and allowed small details to go out and gather timber to build platforms for the men to stand on. Softening a bit more, he also sent 700 prisoners to Selma to ease the overcrowding.

Nine days later, as the last of the waters drained from the stockade grounds, Jones told the incredulous prisoners that he was going to parole them all.

It was no act of charity on Jones’ part; with the war winding down, Grant had relented on prisoner exchanges. For four weeks steamboats plied the Alabama River with prisoners from Cahaba. Most were taken to a neutral site outside Vicksburg called Camp Fisk to await formal exchange. On April 14, Union department commander Maj. Gen. Napoleon J.T. Dana telegraphed the War Department that 4,700 Federals were at Camp Fisk awaiting transportation home. Of that number, he said, 1,100 were sick, nearly all of whom were from Andersonville. “The rest of the prisoners,” Dana reported, “are in excellent health, the Cahaba prisoners particularly.”

Camp Fisk was the creation of Henderson and his Union counterpart, Colonel A.C. Fisk. When he learned exchanges were to be resumed, Henderson asked Fisk to send supplies to the prisoners at Cahaba. Fisk suggested instead that Henderson bring the men to neutral ground near Vicksburg, where they would be guaranteed ample rations and medical attention. Henderson agreed and enthusiastically hastened the transfers.

But the humane work of Henderson and Fisk ended in an unimaginable tragedy. On April 24, the paddle steamer SS Sultana left Vicksburg crammed with approximately 2,000 Union prisoners, more than half of them Cahaba men. The Sultana had bad boilers and a legal capacity of 376 passengers. Early on the morning of April 27, three of the four boilers exploded, and the Sultana sank near Memphis. Two-thirds of those on board died.

The notorious Captain Hanchett had perished several days earlier. With the war over and no one to convene a court-martial of the presumed spy, Colonel Jones took matters into his own hands and murdered Hanchett. Not long after, Jones vanished from history. Federal authorities tried for a year to find him. If they had, Jones might have been the only Confederate prison official besides Andersonville Commandant Henry Wirz executed for war crimes.

General Dana made certain no harm came to Colonel Henderson. For as long as he superintended exchanges at Camp Fisk, a battalion of Union cavalry was assigned as Henderson’s personal bodyguard. But after John Wilkes Booth killed President Lincoln, no Confederate, no matter how well-meaning, was safe within Union lines. So Dana spirited him across the Mississippi River into a camp of Texas Rangers.

Henderson died in Cincinnati in 1912. Obituaries incorrectly said Henderson had been a Confederate brigadier general and omitted any mention of his duty as commandant of Cahaba prison. No matter. Few readers would have recognized the name Cahaba, and none could have found the place had they wanted. After the flood of 1865, the county seat moved to Selma.

Within a decade white residents had dismantled their homes and churches and moved away. At the turn of the century a former slave bought the abandoned warehouse and demolished it for the bricks. Cahaba prison remained only in memoirs and fading memories.

Peter Cozzens is the author of 16 books on the Civil War and the American West. His latest offering is Shenandoah 1862 (2008, University of North Carolina Press).