Even coming on the heels of his vow to lead the United States to the moon ahead of the Soviets, President John F. Kennedy’s bombshell about building the world’s fastest commercial airliner astonished the audience at the Air Force Academy on June 5, 1963. Kennedy said the government would team with private industry to quickly develop “the prototype of a commercially successful supersonic transport superior to that being built in any other country,” a reference to the planned Anglo-French Concorde. Speaking privately about the French leader who promoted the Concorde most aggressively, Kennedy expressed himself more candidly: “We’ll beat that bastard de Gaulle.”

Pan Am President Juan Trippe had announced the day before that his global airline was taking options on six of the 1,450-mph Concordes. Trippe’s announcement, following options from Britain’s BOAC and Air France, threatened not only America’s aviation leadership but also its balance of payments.

Kennedy had been encouraged by a multiagency committee headed by Vice President Lyndon Johnson that had studied the feasibility of building an SST bigger and faster than the Concorde. Aerospace designers assured them it was possible to build an airliner capable of cruising at nearly 2,000 mph, three times the speed of jetliners introduced only a few years earlier. Fighters and bombers were already routinely breaking the sound barrier, and the Air Force’s 2,000-mph XB-70 was in the works. But if such an extreme airliner was technically feasible, Kennedy sorely underestimated the challenges. Projections to Congress that the SST could be built for no more than $1 billion were far off the mark. Kennedy’s dream would require an airplane that could zip through the thin air at 60,000 feet and beyond without being incinerated by the heat it generated. Its engines would have to propel the 275-ton craft at bullet speeds for hours flying between international cities.

When an FAA project team created by administrator Najeeb Halaby spelled out its initial objectives to potential airframe and engine bidders in August 1963, it underlined the scope of those challenges. Operating safely at extreme speeds and altitudes would be the top priority, of course, but builders would also have to minimize the environmental impact, with limits on noise, including sonic booms. The team also demanded that builders demonstrate their SST could be “economically viable.” Kennedy didn’t live to confront those challenges. His November 1963 assassination would leave them to his successors, Johnson and Richard Nixon.

Although the U.S. was getting into the race behind the Concorde and Soviet Tu-144, the SST Kennedy envisioned would be faster and more efficient than either. In their haste to be first, the Europeans had sacrificed the potential to grow in speed or in size. Some skeptics worried that Kennedy’s urgency could lead U.S. manufacturers into a separate trap, with too little time to build a plane that could safely operate at supersonic speeds. They reminded officials that Europeans had jumped ahead of U.S. industry in the 1950s with Britain’s Comet, but had fallen behind after crashes forced a redesign of the Comet fleet.

After months of review, the FAA asked four aerospace companies to refine their proposals. General Electric and Pratt & Whitney were designated to submit final proposals to provide the engines, Boeing and Lockheed to build the airframe. But when GE and Boeing were selected on New Year’s Eve 1966 as the team to build two prototypes, their celebrations were short-lived.

GE had proposed a souped-up version of its YJ93 turbojet engine, already tested for the XB-70. Designated the GE4, it would achieve supersonic speeds through the world’s largest afterburner. Cooling passages drilled lengthwise in the turbine blades helped it survive 2,300-degree operating temperatures.

Boeing’s winning airframe looked much like Lockheed’s entry. Both companies had proposed lancelike aircraft about as long as a football field, fabricated of titanium. Both offered adjustable needle noses to give pilots better visibility.

Lockheed’s design, modeled after a secret reconnaissance aircraft that later gained fame as the SR-71 Blackbird, was to be faster, at Mach 3 (approximately 2,100 mph), than Boeing’s Mach 2.7 (1,800 mph) design. Lockheed’s entry had been redesigned during the competition to bring it nearer Boeing’s 300-passenger capacity.

Boeing engineers had proposed variable-geometry wings, unprecedented in civilian aircraft. Unlike Lockheed’s fixed double-delta wings, Boeing’s wings would sweep back for supersonic flight, a concept based on its swing-wing design proposal for the TFX multiservice fighter (although the Department of Defense had opted for General Dynamics’ design, which became the F-111). As Boeing approached the September 1966 deadline for final airframe and engine designs, its engineers struggled to adapt the fighter design to a 300-passenger airliner. They were forced to enlarge the wing pivots and ask GE for more power as they moved the four engines farther aft. The firms barely made the deadline, but problems intensified.

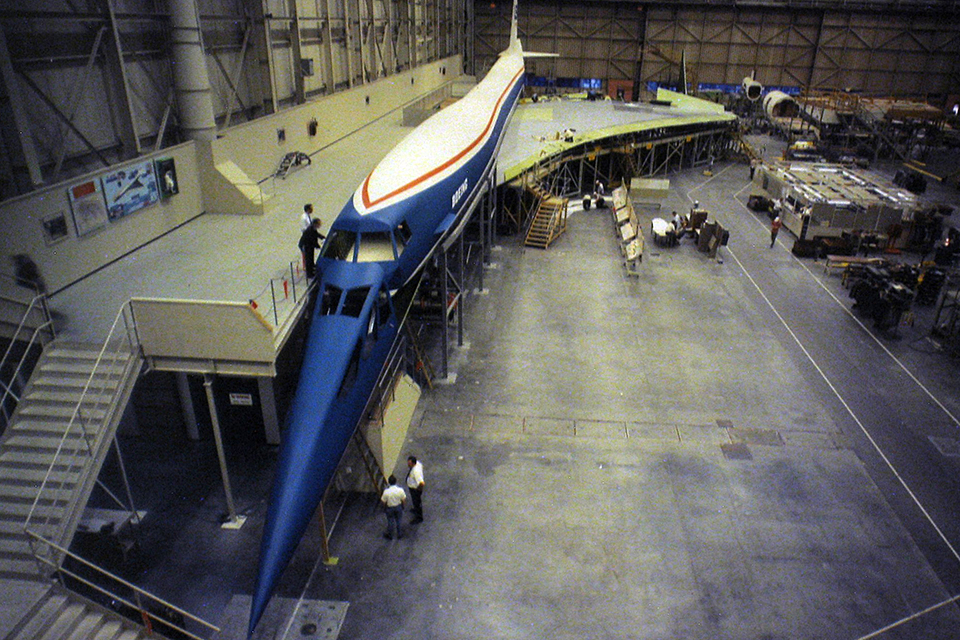

Weight estimates for Boeing’s SST burgeoned from 450,000 to 675,000 pounds by 1967, threatening to curtail its range or reduce passenger capacity. Greater weight would also magnify the sonic boom, which had already caused lawmakers to ban supersonic SST flights over U.S. land areas. The company trimmed as much as 50,000 pounds from the design, but it wasn’t enough. When Boeing rolled out a new mockup at a Seattle hangar in June 1970, the swing wings were gone, replaced by what looked a lot like Lockheed’s rejected double-delta wings.

By 1970 the program was coming under accelerated attack from critics, who questioned whether taxpayers’ money should underwrite 90 percent of a civilian project whose necessity had yet to be demonstrated. The media joined in denouncing its cost and perceived environmental impact. Many echoed the feelings of Sir William Hildred, director general of the International Air Transport Association, who had warned that the SST’s price and operating costs would cripple the airline industry.“I hope I shall not live to see the damn thing,” Sir William railed.

Nixon, who like Kennedy and Johnson had supported the project, fought back by appointing Lockheed’s William Magruder as the third SST program director, following Gordon Bain and Air Force Maj. Gen. Jewell Maxwell. Magruder, an articulate battler with a crew cut and a winning manner, toured the country denouncing “alarmist” critics. But many in Congress were becoming restless.

The showdown came in May 1971, as the Senate weighed in on an $83.5 million appropriation to continue constructing two prototypes. Supporters argued it was foolish to cancel the program when $1 billion had already been spent, pointing out that 26 airlines still had orders for 122 SSTs on the books. Yet in a final vote the Senate ended the program by a 58-39 margin.

Much of the blame (or credit) for the defeat was assigned to environmental groups, one of which had proclaimed in ads that the SST would break windows, stampede cattle and “hasten the end of the American wilderness.” But the Senate debate focused mostly on whether the airliner made economic sense. In the end, most senators concluded it did not. Even Boeing, GE and most airlines had their doubts. With air travel slumping and fuel prices soaring, many airline executives concluded they couldn’t afford a revolutionary aircraft whose estimated price had climbed to nearly $40 million apiece.

If flagging industry support helped ground the SST, even some early proponents looked back on it later as a mercy killing. Given rising fuel prices, former FAA administrator Halaby sadly concluded, “An American SST would have been a financial disaster for all concerned: manufacturer, government and airlines alike.” Modern skeptics point to the Concorde, which despite its VIP mystique was rejected as a money-loser by virtually all the world’s airlines. Air France and British Airways finally retired it in October 2003.

SST advocates clearly miscalculated when they assumed that speed would shape the air transport industry into the 21st century, as it had in the past. In fact, the greatest gamechanger proved to be widebody aircraft such as the 747, the first of which was taking form in a Boeing hangar even as the company assembled its SST mockup.

Terminating the program idled 13,000 workers in a U.S. aerospace industry already reeling from national economic problems. “Boeing came within an eyelash of bankruptcy,” President Phil Condit admitted 25 years later. Yet Boeing survived to remain the world’s leading airline manufacturer. GE lost 1,600 employees, but gained know-how that helped it become the leading jet engine manufacturer. Managers of both firms moved on to other projects, some facilitated by technology developed through their venture into the extreme. The knowledge they gained would help the aerospace industry design and build jetliners in ensuing years that, if not necessarily faster, were safer, more efficient and more reliable than ever before.

Originally published in the May 2012 issue of Aviation History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.