On an unseasonably hot afternoon in Charleston, S.C., last fall, a few intrepid civil warriors were fully prepared for a boat “assault” on a small fortress in Charleston Harbor.

Sunscreen. Check.

Life jackets. Check.

Cough suppressant topical analgesic. Ah…check?

Our major worry during the one-mile cruise from the Carolina Yacht Club to Castle Pinckney—the long-abandoned Civil War fortress on obscure Shutes Folly—was whether we could stand the stench of the myriad droppings of pelicans, the tiny marsh island’s main inhabitants. So we figured a coating of chest rub (a.k.a. “topical analgesic”) under our snouts might blunt the work of the pesky Pinckney pelicans.

We needn’t have worried. The odor wasn’t nearly as bad as we were led to believe. Stepping past a rat carcass or two was a far greater challenge.

Our visit, the final event of the excellent Center for Civil War Photography “Image of War” seminar, was optional. Only 10 bold souls decided to go to the island fortress—which exists merely as a curiosity for most Charleston sightseers and boaters. To access the historic property, which is not open to the public, special permission was secured in advance from its current owners: the local Sons of Confederate Veterans post.

Scores of photographs were taken at the fort during the Civil War, so our main aim was to identify present-day sites of those images. Of course, for us history nerds, an opportunity to explore the seldom-seen site was too tantalizing to pass up. Who wouldn’t want to see the first plot of land ever seized by the Confederate military?

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]onstructed in 1809-10 to replace an earlier log-and-earth fort, the brick-and-mortar Castle Pinckney, named after South Carolina politician Charles Pinckney, guarded Charleston Harbor during the War of 1812. Given its feudal appearance, it was called a “castle.” During that 2½-year conflict, the fort saw no action. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Castle Pinckney was part of the defenses of Charleston and the U.S. Army maintained a limited presence there.

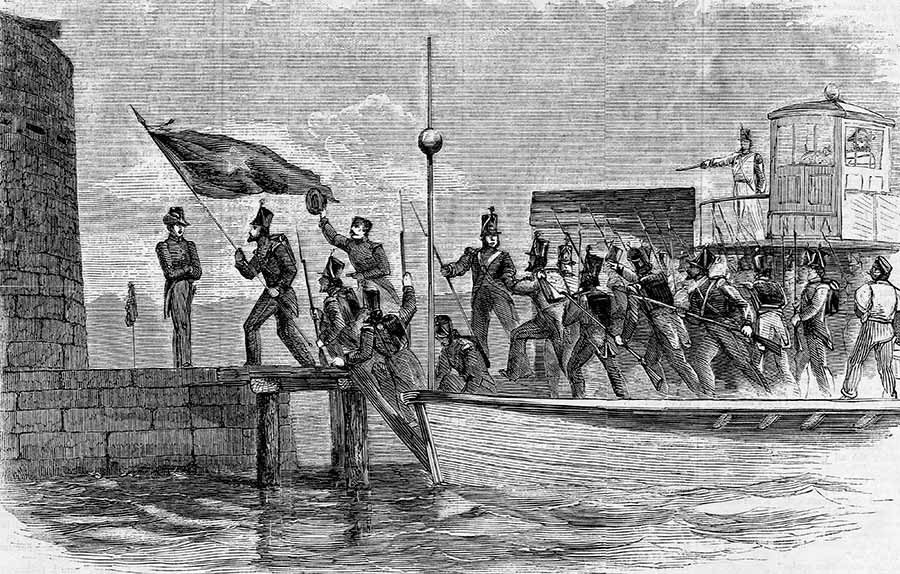

Then came the winter of 1860–61. War fever was intense. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. A week later, a 150-man battalion of South Carolina militia led by Colonel James J. Pettigrew gathered on the green at The Citadel in Charleston. The soldiers, most of whom were unaware of their destination, boarded the steamer Nina, which immediately headed for Castle Pinckney. The Federal bastion was manned by a commanding officer, an ordnance sergeant, four mechanics, and 30 laborers.

Reported a Charleston newspaper on December 28, 1860: “On nearing the fort, a number of men were observed on the wharf, one of whom, in advance of the others, was observed holding what appeared to be a paper in his hand. This was said to have been the Riot Act.” Presumably, the fort’s commander intended to dissuade further action by the intruders by publicly reading them the Riot Act, thus officially placing them on notice that their assembly was unlawful and thereby subject to the use of force.

Riot Act or not, the bare-bones garrison relinquished the installation, eventually withdrawing to Fort Sumter, nearly three miles farther out into the harbor. Lieutenant Richard K. Meade, the commanding officer, refused parole and joined the Union garrison in Fort Sumter. After that fort’s surrender, he was released along with the rest of the garrison. But with the secession of Virginia, he would resign and join the Confederacy.

In another interesting twist, among the troops that captured Castle Pinckney were the Meagher Guards, named after Irish nationalist leader Thomas Francis Meagher, who later became a renowned Union officer. (On St. Patrick’s Day 1853 at Charleston’s Hibernian Society, the fiery Meagher delivered a speech so impressive that an honorary membership was conferred upon him. His membership was revoked in 1861 by the society, noting Meagher “has been carried away by the fanaticism of the North, and has enrolled himself in the ranks of our enemies, taking arms against us in this most unholy war.” No surprise that the Meagher Guard was renamed the Emerald Light Infantry.)

Meanwhile, a Northern newspaper soon speculated how Castle Pinckney might be returned to the Union fold. “[I]n case it should become necessary to land national troops at Charleston,” The New York Times reported in early January 1861, “[Castle Pinckney’s] capture, which would be an indispensable preliminary, might give serious trouble. Perhaps, however, a broadside from one of our new frigates of weighty armament might suffice for the business.” Despite the bluster, the Union Navy never got close enough to pull off such derring-do.

On April 12, 1861, Castle Pinckney provided a bird’s-eye view of the Rebels’ shelling of Fort Sumter, which ignited the Civil War. Three months later, the fort served as a prison for more than 150 Union soldiers who had been captured at the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas). Those captives, according to a Southern newspaper, were selected “chiefly from among those…who had evinced the most insolent and insubordinate disposition.”

During the day, prisoners wandered freely about the place. At night, they were confined to cells in the fort. After six weeks, the castle proved to be inadequate for permanent confinement, and prisoners were transferred back to Charleston. On December 12, 1861, the POWs were hauled back to Castle Pinckney because a massive fire had destroyed a vast swath of the city, including the jail where the Federals were held. “How the Yankees will howl with delight,” a South Carolina newspaper wrote about the disaster. “How their churches will thunder with hallelujah over this visitation from their God.” Union captives remained at the fort for a little more than a week before they were transferred elsewhere.

In 1861, Federal POWs at the castle proved compelling subject matter for a Southern photographer. Judging from the prisoners’ appearance in those images, captivity at the fort was a far cry from the horrors of Andersonville and other Southern prisons later in the war.

Proving their senses of humor were still intact, 21 Federal POWs, members of a Zouave regiment, posed in a photograph near an entranceway and below a hand-made sign that read “Hotel de Zouave.” In another image, Yankee prisoners gathered near the casemate by an entranceway and under a hand-painted sign that read “Music Hall, 444 Broadway.” In that same photograph, more than two dozen of the Union soldiers’ captors—including four by a massive cannon tube—relaxed above them on a parapet.

Of course, for Yankee prisoners, Castle Pinckney was more or less unappealing. “Our greatest need is clothing,” a Union POW wrote to his brother in November 1861. “The men, particularly, require everything from shoes to overcoats.” At least one Southern soldier also found Charleston and the fort on the harbor island especially bleak.

“I arrived here last night and am sorry I ever saw such a place,” the young Rebel wrote in a letter to a friend in the spring of 1861. “If I could get out of it, I would do so with the utmost pleasure. We arrived here Sunday morning at 9 o’clock, and were immediately taken to Castle Pinckney, where we were set to work (on Sunday morning, too) transporting two heavy 48-pounders to the wharf.

“We are treated worse than negroes here. We don’t get enough to eat, and what we do get is the coursest [sic] and most common description. If you hear of anyone getting the Southern Rights Fever as strongly as I had it, just show them this, and if it does not cure him, nothing will.”

During the Union siege of Charleston in 1863, Castle Pinckney was targeted infrequently, mainly because of black POWs being held there beginning in July. According to the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery regimental history, gunners on Morris Island—a little more than three miles away—targeted Pinckney with a 200-pound Parrott on June 29, 1863:

“[T]hree out of five shots smote the castle. We dropped our shells into Charleston whenever we pleased; but the size of the castle made it the smallest armed target that we had selected; and its occupants, feeling that they were exempt from our regards, and safe, were sitting and strolling about on the work. Our magnificent shots produced among them an indescribable excitement. From that hour the work began to undergo a change, and soon, by sand-bags and timbers, it became transformed into quite a solid earthwork. Yet it was never regarded as a point of vital military importance.”

For the most part, the castle remained out of sight and out of mind of Federal military forces. Union troops finally reoccupied the fort after the Confederates abandoned it on February 18, 1865.

Fittingly perhaps, Castle Pinckney drifted into obscurity after the Civil War. For a short time, it was used as a prison, housing vagrants and other civilian prisoners. There’s even a story of the execution of mutinous black prisoners, whose remains reportedly were buried somewhere on the island, perhaps in the fort structure itself.

Sometime after the war, Castle Pinckney’s interior was filled with tons of sand, probably from a nearby sandbar. A large warehouse and caretaker’s dwelling were constructed, and a lighthouse to guide ships in the harbor was added on the island.

In 1897, a bill was introduced in Congress by a South Carolina senator to turn Shutes Folly and Castle Pinckney—described as a location of “great beauty and salubrity”—into a rest home for disabled veterans and other U.S. Army and Navy personnel. “The matter certainly has support of all South Carolina,” The National Tribune, a newspaper for Union veterans noted, “and the press of Charleston has given it much space. It is intended as a sort of social and patriotic peace offering. The people of the birthplace of the rebellion want to take part in the new era of National sentiment that pervades the country.”

But despite the backing of the Charleston Grand Army of the Republic post as well as the governor of South Carolina and mayor of Charleston, the proposal went nowhere.

By 1899, Castle Pinckney was “practically a wreck,” according to a newspaper report, “and useless for further purposes of defense.”

“While a little over 100 years old,” the Baltimore Sun noted, “Castle Pinckney has been overshadowed by more historic and more effective forts in the harbor—Moultrie and Sumter—in the hearts of the people.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘Castle Pinckney has been overshadowed by more historic and more effective forts in the harbor…in the hearts of the people’ -Baltimore Sun[/quote]

On June 6, 1902, Castle Pinckney, used for storage, narrowly escaped destruction late one night thanks to the “violent barking of watch dogs,” who roused the keeper from his slumber. Wooden casks had somehow been set ablaze, threatening to ignite a nearby oil house that held 15,000 gallons of kerosene. The keeper and his family rolled the casks into the harbor, saving themselves and 12 sleeping inhabitants. “The flames were sweeping with such headway when discovered that the oil house would have exploded within ten minutes,” a local newspaper reported, “and the entire island property would have been destroyed.”

In 1924, Castle Pinckney was given national monument status, but the federal government eventually soured on that, largely because of its inauspicious Civil War history. It lost its august designation in 1956. (Nevertheless, in 1970 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.)

By 1958, Castle Pinckney was taken off the hands of the federal government for $12,000 by the South Carolina State Ports Authority, which intended to use it as a dump for soil dredged from the harbor. In 1967, another fire on the island destroyed an old, wooden structure associated with the lighthouse. Vacant for years, it had been a frequent target of vandals. Various plans to restore the fort hit dead ends, and it was sold by the state to the Fort Sumter Camp No. 1269, Sons of Confederate Veterans, in 2011 for $10 Confederate, seemingly a bargain. “We didn’t want to see something out there like a sports bar, with neon lights,” Philip Middleton, the SCV commander, said at the time.

Motivated by buried treasure of a sort, Middleton wants to someday excavate the fort. “We know there are two and perhaps four large Civil War cannon there,” he said recently. “We would like to be able to retrieve them and put them on display.” But such work, Middleton admitted, would be “tedious and incredibly expensive.”

Soon after the small boat with our curious group landed on Shutes Folly, we realized a harsh reality. Battered by time and the elements, the fort’s exterior is deteriorating. A pile of bricks, perhaps some dating to the Civil War, lay near its massive, exterior wall. The muddy route to the fort’s lone entrance was choked by weeds and debris. Nimbleness was required to make our way through the narrow brick gateway, up a steep hill and into the foreboding castle. Near that entrance, we identified the location of a postwar image of a young African-American, a thrill for some of us.

Amid palm trees and island scrub in the fort’s interior, we examined an old gun port and ruins of a postwar chimney. In the far distance, the majestic Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge gleamed in the sunlight. At least one of us imagined from our amazing vantage point the arc of Union cannon fire in Charleston Harbor during the 1863 siege.

Given vast changes since the Civil War, we speculated about sites of wartime images taken inside the fort. Pointing to an exterior wall, one of our group surmised he had found where the young Charleston Zouave Cadets had posed in 1861. Thankfully, scores of pelicans seemed largely unmoved by our presence.

Some of us wondered what else might lie beneath tons of sand and debris dumped at Castle Pinckney long ago. Civil War ordnance? The remains of the prison for Union POWs?

A pelican graveyard?

Perhaps someday Fort Sumter’s poor stepchild in Charleston Harbor will give up those secrets.

John Banks, a regular America’s Civil War contributor, is author of two books on the Civil War, Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers, both by The History Press. He thanks Craig Swain for his contributions to this story.