Captain Jay Zeamer Jr. was still awake when his phone rang at 10 p.m., just hours before he and his B-17 crew were to take off early on June 16, 1943, for a risky photomapping mission. It was an operations officer from V Bomber Command. Naval intelligence had received word of increased activity at the Japanese airfield on the small island of Buka, just north of Bougainville. Before surveying and photographing the hidden reefs of Bougainville’s Empress Augusta Bay—where American troops were to land in a few months—Zeamer was to swing Old 666 north and reconnoiter Buka Airfield.

The request made perfect sense strategically. When the invasion of Bougainville commenced, the Japanese defenses would consist of aircraft from both islands. Still, this new proposal sat in Zeamer’s stomach like a broken bottle. He and navigator Ruby Johnston had already calculated that it would take 22 minutes to photograph the 127 miles of coast along the bay. All the while, it would be necessary to keep the B-17 straight and level at 25,000 feet to ensure the proper overlap of each photo frame that photographer and waist gunner George Kendrick would snap. During the entire mapping run, the lone bomber would be a big, fat target. And now Group Operations wanted to widen that bull’s-eye by adding a Buka recon? Why not just radio the Japanese their course and arrival time?

“Hell no,” Zeamer barked at the operations officer. “I’m only going on the one mission and I’m not letting anyone fool with that.”

Zeamer was still intent on ignoring the order when he set the Flying Fortress to head north-by-northeast shortly after 4 a.m. the next morning. It struck him, not for the first time, how difficult it was to target even familiar islands over dark stretches of the featureless Pacific Ocean. He and his crew had never before set course for Bougainville, and over such alien seas the water below took on the resemblance of a great, gray sinuous muscle, swelling and contracting with the rhythms of the planet. Every one of his crew recognized the importance of this mission as the next step to the Southwest Pacific campaign, and perhaps even to the entire war. Yet flying over so great an expanse made them feel lonely and small.

Three hours later, a thin sliver of sun appeared in the east just as Bougainville’s coastline came into view, a parenthesis of land surrounded by glistening dark waters. Zeamer checked his instruments. One hundred fifty-five degrees east longitude. Then he looked at his watch. Thirty minutes ahead of schedule. It would still be another 30 to 45 minutes before the light would be strong enough to provide the proper exposure for the camera’s infrared filters. That meant he faced a hard choice.

Zeamer reached for his interphone and laid out their options. He could turn Old 666 northwest and kill extra time vectoring over the pale green waters of the Solomon Sea. Out of sight. Safe. Or he could set a course due north and arrive over Buka Passage just as the sun was high enough to photograph the Japanese airfield on the tiny island. He put the decision to the crew.

As top turret gunner Johnnie Able later explained, “We thought so much of Captain Zeamer and had such trust in him and his ability that we didn’t give a damn where we went, just so long as he wanted to go there. Anything okay by him was okay by us.”

Or, as Zeamer interpreted the collective response from his crew that morning: “Oh, what the hell. Let’s take their GD reconnaissance photos. We’ve done it before.”

At 25,000 feet the seahorse-shaped spit of sand looked like a dangling appendage of Bougainville, separated from the larger landmass by only a narrow passage of water. Streaks of pale sunlight illuminated the waves building over the serrated reefs and breaking on Buka’s white-sand beaches. Zeamer saw the airstrip running adjacent to the island’s southeast coast, surrounded by a honeycomb of earthen revetments carved out of the jungle. From five miles above, the rutted roads connecting the aircraft hidey-holes lent the impression of a massive spiderweb encircling the crushed-coral runway that stretched for almost half a mile.

Then, with Old 666 nearly on top of the strip, belly gunner Forrest Dillman reported sighting more than 20 enemy fighters parked wingtip to wingtip, with what looked like perhaps another dozen protruding from their revetments. A peculiar shiver ran up Zeamer’s spine as the risks of the mission suddenly increased exponentially. Had he made a deadly mistake? Why hadn’t he trusted his first instinct? Seconds later, Dillman’s voice again crackled over the interphone. Pilots on the ground were scrambling into their cockpits.

They had been spotted.

ZEAMER, 24, RANKLED COLLEAGUES at the 43rd Bomb Group with his knack for nonconformity. Aloof, they had called him. A screw-up. No respect for authority. When they would not give him a crew, he had recruited one with men like himself; at first they had called them misfits, but now each one was an airman with whom he would entrust his life.

When they would not give him a plane, he and his crew had foraged one—plucked from the boneyard at the rump end of the runway at their base at Port Moresby, New Guinea—and rebuilt it from the wheels up. Old 666, an “E” model, derived its name from its tail number: 41-2666. The crew also increased the aircraft’s defensive armament, replacing its .30-caliber nose guns with larger .50-caliber machine guns and specially fitting a nose gun connected to Zeamer’s cockpit controls. In addition, they added extra guns at the waist and radioman’s positions. With a total of 19 .50-caliber machine guns, Old 666 bristled like a porcupine.

And when they would not give Zeamer assignments, he had volunteered for them—recon missions no one else wanted, missions they all had to be a little crazy to take on. Missions like this one.

No wonder Zeamer and his men had become known as the “Eager Beavers.”

Every man aboard Old 666 recognized it was only a matter of time before the enemy fighters from Buka caught up with them. For a split second Zeamer considered turning and running, scrapping the Bougainville mission altogether. They had gotten the photos of the airfield, so the mission would not be a complete washout. But there were the 37,000 Marines and GIs preparing for the Bougainville invasion. He imagined LSTs snagged on the jagged reefs of Empress Augusta Bay. The Marines and GIs would be ducks in a pond for the machine guns and mortar tubes around the invasion site. He turned the bomber south. Bougainville lay before him like a green mirage on a sea of blue.

Back in the waist, Kendrick snapped photo after photo; down in the nose, bombardier Joe Sarnoski—at 28, the oldest and most experienced crew member—assisted Ruby Johnston with monitoring the aircraft’s drift, airspeed, and altitude. And up on the flight deck, Zeamer and copilot J. T. Britton watched as all cameras clicked like clockwork on the cockpit’s intervalometer, a device that triggered the cameras’ lens shutters for time-lapse exposures.

A minute that seemed like an eternity passed before tail gunner Herbert “Pudge” Pugh reported another Japanese fighter squadron lifting off from Bougainville’s Buin Airfield. He counted perhaps a dozen attackers. A lone B-17 could reasonably expect to hold its own against six enemy bandits in a fight, maybe seven or eight on a good day. With all its extra guns, Zeamer was confident Old 666 could even take on nine or 10 in a pinch. But 20? And with more likely to follow in their wake? Suicide.

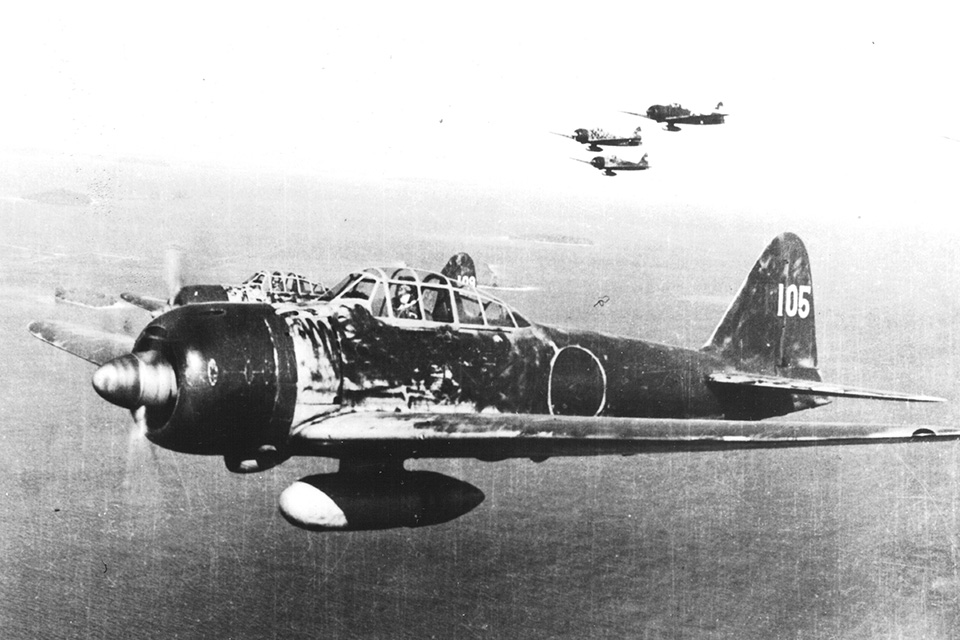

Zeamer kept Old 666 heading straight and true as Kendrick focused his cameras on the ribs of coral shimmering just below the bay’s surface. After 10 minutes, Kendrick’s voice broke the cockpit’s droning hum. “Give me 45 more seconds.” The words were barely out of the waist gunner’s mouth when Zeamer spotted the first wave of Japanese fighters—four green A6M Zeros and a twin-engine fighter—climbing and circling around their plane.

Dillman and Pugh aimed bursts of fire at the fighters, forcing them to swerve, but they regrouped and circled to make a frontal attack, where the B-17’s armament was normally weakest. Within seconds, the five aircraft covered Zeamer’s Flying Fortress like a shroud. A Zero with vertical red stripes painted across its fuselage made its run at the precise moment Kendrick asked for another 15 seconds. Zeamer saw it approach from the 10 o’clock position and roll onto its back before firing. Down in the front compartment, just behind the B-17’s Plexiglas nose, Sarnoski responded with a burst of fire, sending the Zero into a spin. The B-17 shuddered as the rest of the crew blasted the enemy swarm.

As Sarnoski took aim at another Zero, a Japanese 20mm cannon shell punched through the B-17’s nose, exploding in the front compartment. The force blew Sarnoski back 15 feet. He landed facedown with a bone-jarring thud on the aluminum floor almost directly beneath the flight deck. The concussion also knocked Ruby Johnston off his feet, but he was able to recover and crawl on all fours toward Sarnoski. He rolled the bombardier over and flinched. The exploding shell had lacerated Sarnoski’s neck and ripped a bowling ball-sized hole in his side.

Johnston ripped open packets of sulfa powder and doused the wounds. Sarnoski’s eyelids fluttered, then flipped open. His eyes were red and beginning to swell from the Plexiglas dust they had absorbed when the nose shattered. “I’m all right,” Sarnoski managed to say. “Don’t worry about me.” Gouts of blood spilled onto the floor as he spoke. Johnston poured more sulfa on the wounds. Frigid air, rushing in through the shattered nose, was starting to freeze the front compartment. The blood on Sarnoski’s face and torso coagulated into a slushy sheen.

Sarnoski slowly crab-walked back to his shattered station like a snail leaving a trail of gore. He gripped a machine gun and pulled himself into a crouch, firing at the twin-engine fighter and setting it ablaze; it dove and disappeared from view. The wind streaming through the broken Plexiglas slammed empty shell casings back into Sarnoski’s face. Yet he continued to fire until he collapsed.

Up in the cockpit, Zeamer spotted a Zero coming straight at them. He adjusted his rudder pedals, got the bandit in his crosshairs, and pressed his thumb trigger to fire Old 666’s nose gun. His eyes were on the Zero as it twirled toward the water when his cockpit erupted in an effulgence of colors—white, magenta, orange—a rainbow blast accompanied by a sudden wave of acute pain. A thick acrid smell filled his nostrils. “Is this it?” he wondered.

Machine-gun fire from the top turret just behind him refocused his thoughts, and he scanned the flight deck. Britton, the copilot, was slumped forward in the right seat, his eyes closed and his chin on his chest. The cannon shell had blown away the B-17’s instrument panel and severed cables connecting the rudders and horizontal stabilizers. The windshield was still intact, but the force of the explosion had torn away the left cockpit window and peeled back the aircraft’s aluminum skin next to Zeamer’s seat. The cacophony of the roaring Wright Cyclone engines and the wild rush of the slipstream stunned him.

The shell had also torn a gaping hole in the lower bulkhead connecting the cockpit to the front nose compartment. Through the gap, Zeamer could see Johnston firing at his position. Beyond him, he saw Sarnoski slumped over his machine gun. As Zeamer wondered if Sarnoski was in much pain, his own shock wore off. The lower half of his body felt as if it were on fire. His flight clothes were shredded and his left leg was sliced from the calf to the thigh. Thick, ugly sheaves of blackened flesh, like rashers of seared Canadian bacon, dangled from his exposed shinbone. His left knee resembled a mound of raw hamburger meat.

Zeamer soon realized shrapnel had also ripped through his right leg and both arms. With each pump of his heart, a thin stream of pinkish liquid spurted from a nicked artery in his ruptured left wrist and pooled in his lap. With his right hand bleeding, Zeamer keyed the interphone and asked for a damage report. No response. The shell had destroyed the communications system. He cursed under his breath.

The only instruments still working were the manifold pressure gauge and the magnetic compass in the center of the charred dashboard. The extensive damage sharply diminished Zeamer’s ability to maneuver the B-17. He wagered he could selectively slow the engines on each wing to steer the bomber this way and that—if he stayed conscious.

In the copilot’s seat, Britton groaned and lifted his head; his eyes fluttered like a boxer coming to after the count. He patted himself down; he had a large contusion on the back of his head, but no other wounds. With the communications system destroyed, Britton left the cockpit to check on the other crew. He returned to inform Zeamer that Kendrick had stowed the camera film and was manning the waist guns. More critically, enemy bullets had destroyed the yellow, keg-like oxygen tanks behind the cockpit. That left the crew with only their small, personal bottles, which they would quickly deplete. Unless they descended to below 10,000 feet, the crew was in danger of passing out from hypoxia.

Using his ailerons and elevators—miraculously still functioning—Zeamer pushed Old 666 into a steep dive. The plane’s engines screamed and its fuselage groaned as it rapidly gained speed. With the altimeter hanging limply by its frayed wires, Zeamer estimated their altitude by the increases in the engines’ manifold pressure. Old 666’s rivets were rattling when he calculated they had dropped to around 6,000 feet. He leveled off, removed his mask, and took a deep breath. His injured body contorted with pain as he forced air into his lungs, but at least his crew could breathe.

From the top turret, Able yelled that the Japanese fighters were chasing down after them—Kendrick counted 17 Zeros. Zeamer banked the bomber and saw the bandits go racing past for what he assumed would be another frontal assault. One more hit could finish off Old 666. Able knocked out one of the Zeros, which barely missed clipping their right wingtip as it spun toward the water, leaving a contrail of greasy black smoke. Moments later, Able dropped out of his swing-seat harness and crumpled to the ground, wounded in both legs.

Keeping the morning sun over his left shoulder, Zeamer set a southwesterly course. The Japanese fighters relentlessly circled Old 666, making head-on passes. Zeamer lost count—six, eight, a dozen attacks? It was as if the B-17 was flying through a vortex of iron rain, alternating between a light patter and a heavy, deadly downpour.

Furthermore, Zeamer realized he was bleeding out at an alarming rate. His legs were useless and both of his boots had filled with blood. The control wheel was slippery with gore from his wounded arms and he could grip it only with his fingertips. During one lull, he pulled off his belt and tried to tie a tourniquet around his left thigh. The effort proved too painful and time consuming. But there was a benefit to the icy wind whistling in past his legs: it helped staunch the bleeding.

Britton continued to tend to the wounded crew, periodically returning to the cockpit to plead with Zeamer to relinquish control of the aircraft and get patched up. Each time, Zeamer refused; he felt that only he could keep battered Old 666 in the air. At least the pain was keeping him awake.

AFTER 40 MINUTES AND 100 MILES, the Japanese fighters—low on fuel and ammunition—at last began to peel away, unaware the B-17 gunners were down to their final few bullets. But with close to 500 miles of shark-infested waters left to cross before they reached New Guinea’s northern coast, Zeamer knew their ordeal was far from over. There was a good chance he would have to ditch Old 666; he estimated their odds of surviving an ocean crash-landing at about 50 percent. Fortunately, the B-17 tended to stay afloat longer than most other American bombers. But ocean currents and strong winds could push a life raft dozens of miles a day in any direction. If downed airmen were not found within 24 hours, their chances of being rescued were almost none.

One paramount thought, however, overrode all Zeamer’s calculations: they needed to bring back the photographs. Unless they returned to base with their film intact, the entire effort—and all the spilt blood—would be for naught. The Bougainville invasion would fail, and he refused to let another bomber crew go through the same hell they had endured. No, Zeamer decided. He would get this plane home.

Even without his altimeter Zeamer knew Old 666 was steadily losing altitude. The B-17 was “mushing”—its tail dragging below the nose—and the lower it flew, the more fuel it would burn in the denser atmosphere. He could adjust the propeller pitch or change the engines’ air-to-fuel ratio only so much to delay the engines from starving or running too hot. And even if the aircraft managed to remain aloft for the next four hours, it would never be able to clear the Owen Stanley mountain range and make it back home to Port Moresby. Given the amount of blood Zeamer was losing, he was beginning to doubt he would even live that long. Their only hope was to try to reach the 7,000-foot grass airstrip hacked out of the jungle at Dobodura, 90 miles east of Port Moresby. But where were they in relation to Dobodura?

Radio operator Willy Vaughan, his neck wound bandaged with a rag, lurched into the cockpit. He reported that an experimental navy-issue radio set he had picked up in Port Moresby was still working. Its voice mode was out, but he could transmit Morse code. Less than 30 minutes later, an American patrol vessel and Australian coastwatchers picked up Vaughan’s transmission. They used the signal to triangulate a fix on Old 666’s position and relay it to Vaughan, who then plotted a course to Dobodura.

En route, and with the Japanese fighters long gone, Able kept the B-17 on course while Britton and Kendrick finally tended to Zeamer. Britton implored the pilot to move to the catwalk so they could better treat his wounds.

“I don’t move,” Zeamer told them, “until the mission is ended.”

TAIL GUNNER PUDGE PUGH inched forward past the waist guns to the radio compartment. It was warmer in the center of the fuselage, and Pugh lingered to watch Kendrick and Dillman rebandage Willy Vaughn’s neck. When Pugh saw that they had the task under control, he continued forward to the crawlspace leading to the nose. There was blood everywhere. Britton was tending to a wound on Johnston’s head and, further up, Pugh saw Sarnoski collapsed on one of his machine guns. Rivulets of frozen blood formed spidery lines that flowed from Sarnoski’s body. His ammunition belts had all been fired off and one of the machine gun’s barrels was burned out.

Pugh lifted Sarnoski away from the shattered glass and rolled him, face-up, into his lap. He was still alive. Pugh removed Sarnoski’s ever-present rosary from his pocket and pressed it into his friend’s bloody hand. He saw Sarnoski open his eyes once, lift the rosary to his lips, and kiss it. Then Sarnoski closed his eyes and breathed his last. Johnston crawled forward and asked how Sarnoski was doing. “He’s all right,” Pugh uttered. He didn’t know what else to say.

With Zeamer’s condition steadily deteriorating, Britton took over control of Old 666. The sun was almost directly overhead when they spotted the lush Dobodura coastline; Zeamer recognized the familiar outline of the American PT boat base at Oro Bay and the contours of Cape Endiaidere. The Dobodura airstrip was 25 miles beyond. Britton flew Old 666 over the water, banked, and pointed the plane’s nose inland. He could only guess at the wind direction as he throttled back and pulled the wheel into his gut.

The B-17 raced over the airstrip so fast that it looked as if the palm trees were shooting up at them. Zeamer saw the airfield’s rickety control tower flash by on his right and then they hit the dirt hard, bouncing three times. With no functioning brakes, they were approaching the end of the runway much too fast. Britton spun the wheel with all his strength—the B-17’s left wing dipped and dug into the dirt. Chunks of rocks and turf flew like sparks from a grindstone as the aircraft’s skidding, circular movement gradually tightened. Finally, the bomber rolled to a stop at the end of the airstrip in a cloud of dust. The time was 12:15 p.m.

It had been more than eight hours since they had taken off from Port Moresby. When Britton switched off the engines, Zeamer took a deep breath and the world around him receded into nothingness. He came to some time later, unsure of where he was, but in no pain. His body felt numb from head to toe. He heard muffled voices and smelled sizzling oil and leaking fuel. Then another voice, closer and louder, said: “Get the pilot last. He’s dead.”

Zeamer wanted to shout but could not find the strength. Finally, two strong hands unbuckled his safety belt and lifted him by the shoulders. The pain returned, unbearable, and he passed out again. At Dobodura’s small field hospital, doctors examined Zeamer and determined he had lost nearly half the blood in his body. Over the next 72 hours, they carefully removed nearly 150 pieces of shrapnel—including chunks of the plane’s rudder pedals and its control cables—from Zeamer’s legs, arms, and torso.

Fourteen days after Old 666’s mission, Allied forces began Operation Cartwheel, a two-pronged offensive to take Rabaul by pushing through New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. And in November, Marines and GIs stormed ashore on the west coast of Bougainville. Military planners gave much credit for the successful landings to the landing craft drivers who, using maps and charts developed from the photographs taken by Old 666, successfully avoided the deadly reefs lacing Empress Augusta Bay.

During its final flight, Old 666 endured one of the longest sustained attacks by enemy fighters in history. For their valor, Jay Zeamer and Joe Sarnoski were awarded the Medal of Honor. The seven other crewmen—J.T. Britton, William Vaughan, Herbert Pugh, Forrest Dillman, Johnnie Able, Ruby Johnston, and George Kendrick—were each awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest military commendation for heroism. This gave Old 666’s crew the distinction of becoming, and remaining, the most highly decorated combat aircrew in American military service.

Not bad for a bunch of screw-ups and misfits. ✯

Copyright © 2016 by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin. From LUCKY 666: The Impossible Mission by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

This excerpt was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.