Jesse Owens won a coup in Hitler’s Germany, but today’s NBA stars kowtow to China

We Americans love our sports, and so does the world. This year the National Football League slated five regular season games abroad—one in Mexico City, four in London. Baseball has been a hit in Japan and the Caribbean basin since forever. And basketball has a huge following in China, as we learned when the National Basketball Association kowtowed to the Chinese government after the manager of an NBA team expressed an opinion Beijing didn’t like.

The words that shamed the NBA were tweeted by Daryl Morey, general manager of the Houston Rockets, in support of pro-freedom demonstrators in Hong Kong: “Fight for freedom, stand with Hong Kong.” China scolded, Americans folded. Morey apologized. The NBA announced that the Rockets GM’s tweet “does not represent the Rockets” or itself. “We apologize, we love China, we love playing here,” James Harden, the Rockets’ MVP guard, insisted. “We love everything they’re about.” Observed GOAT LeBron James, “We do have freedom of speech, but there can be a lot of negative things that come with that too.”

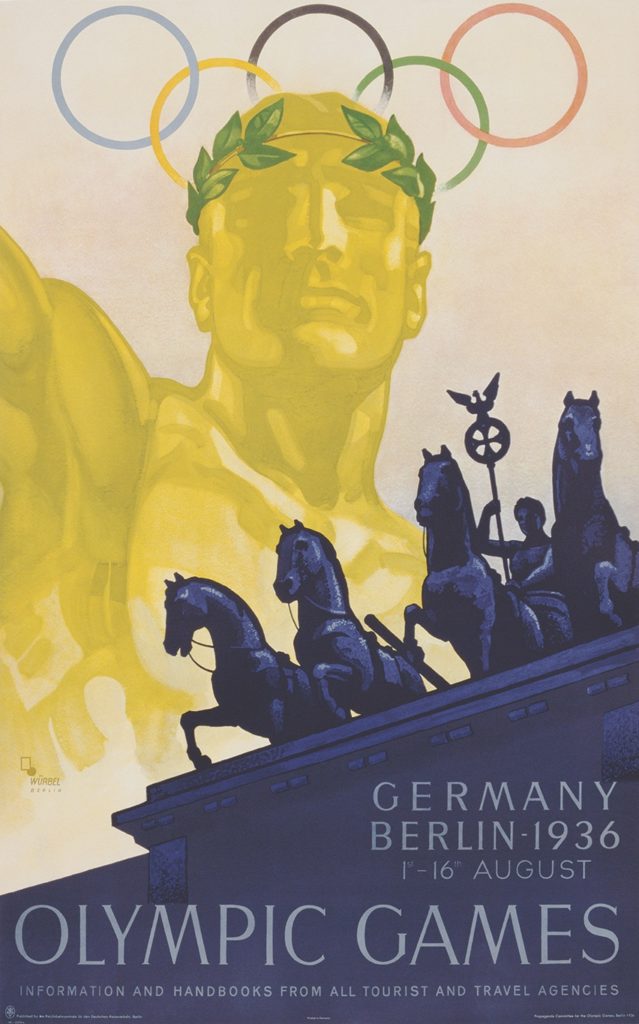

American athletics has fouled before when playing in totalitarian states. The most dramatic instance was the 1936 Olympics. The International Olympic Committee awarded the 1936 summer games to Berlin in 1931, when Germany was still a republic. After Hitler took power in spring 1933, Americans began arguing about America’s participation in a Nazi spectacle. Point man for the status quo in the United States was Avery Brundage, head of the American Olympic Committee. Brundage, by day a builder, was an Olympic vet, having competed—unsuccessfully—as a decathlete and pentathlete at Stockholm in 1912. Brundage was devoted to the ideal of amateur excellence. He was also thin-skinned and dictatorial, an anti-Semite who blamed the “Jewish-controlled press of New York City” for badmouthing the coming games.

Though trumpeted by Nazidom’s natural enemies, Jewish groups and unions, American sentiment against participating in a Nazi Olympics was in fact broad.

Other vocal opponents included urban politicians like New York’s Fiorello LaGuardia and Al Smith and Boston’s James Michael Curley. Christian magazines—Commonweal (Catholic), Christian Century (Protestant)—joined the call for a boycott. Diplomats at the American embassy in Berlin told all who would listen that the Nazis were unworthy hosts; their bosses at the State Department ignored those warnings.

Black organizations and black athletes were of two minds. They did not need Nazi Germany to school them about race-based societies; they knew Jim Crow first-hand. Maybe the way to fight white supremacy would be to send black phenoms like Jesse Owens to Germany to win. An American Olympic squad that was “decidedly brunette,” as Roy Wilkins of the NAACP put it, would “strike a blow against all that Hitler stands for.”

Brundage deflected American critics, making a fact-finding trip to Germany in fall 1934 to assess the regime’s commitment to fairness. He swallowed whatever his Nazi hosts recited. “There will be no discrimination in Berlin against Jews,” Brundage said upon returning. “You can’t ask for more than that.”

The 1936 Winter Olympics took place that February at Garmisch-Partenkirchen. The winter games were a smaller deal than today, and Americans a minor factor; Norway, Germany, Sweden, and Finland dominated. The most noteworthy Yank present may have been cantankerous newspaper columnist Westbrook Pegler, who reported Garmisch to be swarming with swastika-bedecked soldiers. German officials called him a liar. Pegler penned a correction: “Those weren’t troops at all, but merely peace-loving German workmen in their native dress. They just walk in step in columns of four, because they like to walk that way.” The German embassy in Washington instructed consulates to deny Pegler a visa for Berlin.

The Nazis’ goal for the Berlin Olympics, held in August, was to show Germany and the world that they ran a strong, united, efficient National Socialist paradise. But to make points at home and abroad, the Reich had to avoid needlessly inflaming foreign opinion. Universally bad coverage, never mind walkouts or the like at events, would devalue the exercise. So the Nazis tweaked Germany’s totalitarian wardrobe. For the duration, Der Stürmer, that most rabidly anti-Semitic of Nazi tabloids, vanished from Berlin newsstands, replaced by foreign papers, hitherto banned. SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered Hitler’s bodyguards not to carry sidearms. Chief propagandist Josef Goebbels instructed German media to treat non-white foreign athletes fairly, particularly Jesse Owens—though in his diary Goebbels fumed that Owens’s win in the 100-meter dash marked “a day of shame for the white race.” The Germans even included a lone half-Jewish athlete on their women’s fencing team. Helene Mayer, who despite having a Jewish father did not consider herself Jewish, readily gave a Nazi salute when presented a silver medal.

The Berlin games nevertheless remained a triumph of Nazi stagecraft. The torch run from Olympia in Greece across south-central Europe to Berlin was a Party brainstorm, meant to paint ancient Greeks and modern Germans as racially akin; Leni Riefenstahl, the cinematic auteur and Hitler fangirl documenting the summer games, had cameras track the torch’s progress. At the purpose-built Olympiastadion, Germany’s squad paraded to the tune of the national anthem—as well as the “Horst Wessel Lied,” infamous as a stormtrooper fight song. Hitler himself attended, rooting for the Germans, American scribe Grantland Rice wrote, “like a Yale sophomore at the Harvard Game.” The Führer did not, as legend has it, specifically refuse to shake Owens’s hand after the American’s victories. Hitler had decided earlier, after black American high jumpers Cornelius Johnson and David Albritton won gold and silver respectively, that he would shake no athletes’ hands. “Do you really think,” he bellowed in private, “I’d allow myself to be photographed shaking hands with a Negro?” At Berlin Americans won 56 medals, bested only by the host country’s 89. However unwittingly or unwillingly, American athletes had been part of the Nazi extravaganza.

The big differences between the Nazi Olympics and Chinese/American basketball are time and money. The 1936 games, winter and summer, were one-offs involving amateurs; the NBA’s fealty to its Chinese market arises from a lucrative long-term marriage. It is hard to see what would constitute grounds for divorce. World War II put the Olympics on hold for two quadrennial cycles, but a lesser event, like a crackdown on Hong Kong, likely would cause only a ripple in King James’s cash flow.

Would a boycott have dented Hitler? Would stiffer NBA spines impress China today? In protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, 62 countries, led by the United States, boycotted the Moscow Olympics in 1980. The USSR rolled on for 11 more years, done in finally not by athletics but by the expense of the arms race and by Mikhail Gorbachev.

Playing on tyrants’ terms says something, however. Among the most fervent American foes of joining the Nazi Olympics was IOC member Ernest Jahncke. “Let me urge you,” the New Orleans businessman wrote a colleague in the Olympic movement, to “place your great talents in the service of fair play and of chivalry instead of brutality, force and power.”

Good call.

This story appeared in March 2020 issue of American History.