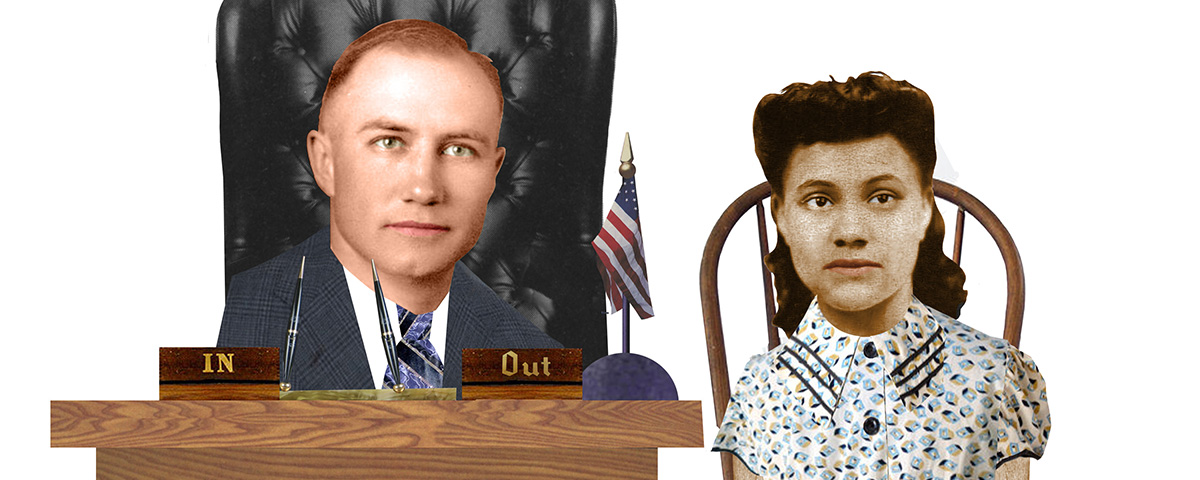

HE WAS 23. She was 15. He was white and rich. She was black and poor. He was Strom Thurmond, son of a powerful lawyer in Edgefield, S.C. She was Carrie Butler, a part-time maid in the Thurmond house. Carrie was pretty, and Strom, a handsome schoolteacher, flirted with her as she went about her work in his parents’ house.

“One thing led to another,” as Butler later put it, and on October 12, 1925, she gave birth to Thurmond’s first child, a girl she named Essie Mae. To avoid scandal, Carrie sent Essie to live with her sister, Mary Washington, in Pennsylvania.

Mary Washington and her husband raised the girl as their daughter. Essie Mae Washington didn’t learn who her real mother was until she was 13, when Carrie Butler, visiting her sister, blurted out the truth: “I’m your mother.”

But Essie Mae had no knowledge about her father’s identity until three years later, in 1941, when she traveled to Edgefield to attend a family funeral. It was her first trip to South Carolina, her first exposure to segregated trains and “whites only” drinking fountains.

Carrie woke Essie Mae early on the morning after the funeral. “Get up and get dressed,” she said. “I’m taking you to meet your father.”

In their finest dresses, Carrie and Essie Mae walked past the shacks of Edgefield’s black ghetto and into the white side of town. Maybe her father worked as a butler for a rich white family, Essie Mae thought. When they arrived at a building with a sign reading, “Thurmond and Thurmond, Attorneys at Law,” Essie Mae figured her father must be a chauffeur for a big-shot white lawyer. When a black servant opened the door, she thought he was her father. But he merely led them to an empty office, where they waited in silence.

A few minutes later, Thurmond, a 38-year-old lawyer and judge, stepped into the room and stared at Essie Mae. “You have a lovely young daughter,” he told Carrie.

Carrie smiled. “Essie Mae,” she said, “meet your father.”

Stunned, she could barely speak. “Hello…Mister…Thurmond.”

“What do you think of our beautiful city?” he asked her.

“It’s different from my home.”

“This is your home, Essie Mae,” he said. “You must think of yourself as a South Carolinian. This is a wonderful city, a wonderful state.” South Carolina is called the Palmetto State, he told her. “Do you know what a palmetto is?”

“No, sir.”

“It’s a small palm tree,” he said, and he pointed to a circle on the wall. “This is our state seal. See the palmetto growing out of that fallen oak? That represents our great victory, from a fort built of palmetto logs, over the British fleet built of oak. That Latin phrase there—Quis Separabit—do you know what that means?”

“No, sir.”

“Take a guess, Essie Mae.”

Carrie laughed. “Your father used to be a schoolteacher,” she explained.

Thurmond put his hand on Essie Mae’s shoulder. “It means, ‘Who can separate us?’”

Recalling that moment in her memoir, Dear Senator, Essie Mae wrote: “I took the comment personally and was deeply flattered by it.”

Thurmond translated another Latin phrase on the seal, then offered some advice: “You must learn Latin, Essie Mae. It’ll help you with a lot of things.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

He pulled out two chairs for his guests. When his hand brushed across Carrie’s hand, he held it there for a moment, and Essie Mae watched as her parents gazed into each other’s eyes. “They were in love, clearly in love,” Essie Mae concluded. “In that split second, I could tell what was going on, and it was as strange to me as seeing aliens from another galaxy.”

The moment passed and Thurmond brought up one of his favorite topics—physical fitness. He studied Essie Mae’s body. “I would stay just as you are, not another pound more,” he said. “Be careful of that fried food, no matter how good it tastes. It can kill you. And drink plenty of water, at least three big glasses a day. And walk everywhere you can.”

“He used to be a coach, too,” Carrie said, and Thurmond laughed.

In their hour together, Thurmond did most of the talking, sitting behind his massive oak desk, delivering little lectures on local history and national politics. Finally Carrie said, “I know you’ve got important work to do.”

He saw them to the door and shook their hands—“the strongest, bone-crushing handshake I had ever experienced,” Essie Mae wrote. Then he took another long look at his daughter. “She has my sister Gertrude’s cheekbones,” he told Carrie. “Isn’t she a lovely girl? You have a lovely daughter.” Essie Mae appreciated the compliment but wished he’d said, “We have a lovely daughter.” She noticed that he’d never actually said that he was her father—and that he didn’t invite her to return.

On their walk back to the black side of town, Carrie told her daughter about her ongoing affair with Thurmond.

“Does he love you?” Essie Mae asked.

“I hope so,” Carrie said. “I think so.”

“Do you love him?”

“Yes.”

“Does he have a wife?”

“No.”

“What can we do?”

“Nothing,” Carrie responded. “This is South Carolina.”

Five years later, in 1947, Thurmond became governor of South Carolina and married a young white beauty queen. In 1948, incensed at President Truman’s civil rights bill, Thurmond ran for president on the States Rights Party ticket, proclaiming: “There’s not enough troops in the Army, to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race into our theatres, into our swimming pools, into our houses and into our churches.” (He did not mention our beds.)

Thurmond lost that race. But in 1954 he was elected to the U.S. Senate, and he remained there until 2003, when he was 100 years old. In 1957 he set a Senate filibustering record by orating for 24 hours and 18 minutes against a civil rights bill. He also filibustered against the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, and when President Lyndon Johnson signed that bill into law, Thurmond deserted the Democratic Party and endorsed Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, who voted against the bill.

Throughout his long career, Thurmond maintained a guarded relationship with his black daughter. He met with Essie Mae frequently, usually in his office, and they occasionally argued about race and politics. Thurmond put her though college and helped to support her family for decades, handing her envelopes containing $100 bills—more than $100,000 over half a century. But he never publicly acknowledged that they were kin.

After he died in 2003, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, then 78, a retired Los Angeles schoolteacher, revealed their kinship, and Thurmond’s white family confirmed it.

“I believed that he loved me,” she wrote in her 2005 memoir. But still, she long lamented that their relationship was warped by her father’s political ambitions and the racial codes that ruled in the Old South.

“He and I had never so much as sat down together for a meal. We had never said ‘I love you’ to each other. We had never confronted the reality of our relationship. Too much remained unsaid.”