In his heyday he was America’s foremost popular composer. Then the demons caught up with him.

THIRTY-EIGHT CENTS AND A SCRAP OF PAPER bearing the wistful words, “dear friends and gentle hearts.”

Such were the aggregate personal effects collected from the worn leather pocketbook of Stephen Collins Foster at the time of his death in New York City’s Bellevue Hospital on January 13, 1864. The small change attested to the reduced circumstances of a man who had once been America’s foremost popular composer. As for the sentiment Foster had recorded on the penciled fragment, it was far removed from the rancorous Civil War that had raged around him for nearly three years.

Foster’s background and experience yield mixed clues to his feelings about the war. There were numerous Democratic connections in his family. His father, William, had been an Andrew Jackson man. Having lost property through foreclosure by the Bank of the United States, he no doubt felt a personal stake in Old Hickory’s campaign against the “Monster Bank.” William had served in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, and his daughter Ann Eliza married the Reverend Edward Buchanan, brother of the rising Democratic politician James Buchanan. Stephen would devote a modicum of his artistic talent to Buchanan’s successful run for president in 1856, including writing a pro-Democratic campaign song, “The White House Chair,” and lyrics for an anti-Republican ditty titled “The Abolition Show.”

Stephen may have left scant evidence of his feelings during the secession crisis, but his brother Morrison, then working in Cleveland, clearly spelled out his own position in a letter to the editor of the Plain Dealer, the city’s Democratic daily. Noting a popular opinion in the North that “it would be better as a matter of interest that the free States were separated from the slave States and become as to them a foreign nation,” the writer declared that he was “not one of those who have adopted this error.” To dissolve the Union “in an insane quarrel over the negro slave,” he concluded, would expose “the painful fact…that the advantages of the Union with the slave States is too often underrated by thoughtless persons in the free states.”

But Morrison signed his letter with the sobriquet “A Union Man,” which suggests another strain in the Foster family’s political DNA. Stephen was born just outside Pittsburgh in 1826, on the very day Declaration of Independence signers John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died—July 4, the great national holiday. Even as his son was entering the world, William Foster was presiding over a banquet in which he raised a toast to “the independence of the United States—acquired by the blood and valor of our venerable progenitors. To us they bequeathed the dear bought inheritance…and the most sacred obligations are upon us to transmit the glorious purchase, unfettered by power, to our innocent and beloved offspring.” Four years later, in the face of South Carolina’s Ordinance of Nullification, Andrew Jackson would distill the same popular sentiment in a toast: “Our Federal Union: It must be preserved!”

The Fosters, then, were Union Democrats; and when South Carolina in 1861 finally did fire on the national flag at Fort Sumter, they were initially disposed to become War Democrats. All right, Stephen seemed to say in his first topical Civil War song, “I’ll Be a Soldier”:

I’ll be a soldier, “my country’s” the cry,

I’ll fly to defend her and conquer or die;

The land of my childhood, my love and my tears,

The land of my birth and my early sunny years.

A year later Foster was one of half a dozen composers stirred to put to music a patriotic poem by James Sloan Gibbons in the New York Evening Post. Following Union reverses in the Seven Days and Second Bull Run Battles, Abraham Lincoln had issued a call for 300,000 more volunteers. Foster’s version of “We Are Coming Father Abraam” was “Respectfully Dedicated to the President of the United States.” Resolute in tone, it lacked the exuberance of a more popular rendition by hymn writer Luther Emerson.

WHILE STILL A COMPOSER TO BE RECKONED WITH, Stephen Foster by the 1860s was no longer the dominant figure in American popular song. His reputation rested primarily on a dozen or so tunes he’d composed from 1848 to 1854, beginning with “Oh! Susanna” and “Camptown Races.” These were followed by such standards as “Old Folks at Home” (popularly known as “Swanee River”), “Massa’s in de Cold Ground,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Dog Tray,” and “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair.” Most of these were written in a supposed “Negro dialect” to capitalize on the rage of the day for blackface minstrel troupes. Foster’s most profitable effort, “Old Folks at Home,” was in fact first introduced in a minstrel act by E. P. Christy.

Foster’s dialect songs were accepted, especially in the North, as the authentic musical voice of African Americans. A Wisconsin soldier, encountering Southern slaves in the Civil War, would write home telling of his surprise at discovering that none of them seemed familiar with Foster’s “colored” songs. Although Foster had visited the slave states twice briefly, any veracity the songs had would more likely have come from Foster’s boyhood exposure to African-American church services in Pittsburgh, through his family’s female mixed-race servant.

Long before the Civil War challenged his political loyalties, Foster had experienced conflicts in his musical ambitions. Out of concern for being typecast as a writer of “Ethiopian” songs, he allowed E. P. Christy to be credited as the composer of “Old Folks” on the sheet music for the song. “His poetic fancy ran rather to sentimental songs,” according to Morrison Foster, who recalled his brother immersing himself in “the works of the masters, especially Mozart, Beethoven, and Weber.”

Stephen had demonstrated considerable talent for the sentimental genre known as parlor songs. Though not as remunerative as his minstrel numbers, songs such as “Some Folks,” “Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming,” and “Gentle Annie” established his credentials for the genteel market. A musical journal of the day frankly expressed the hope that Foster would “soon realize enough from his Ethiopian melodies to enable him to afford to drop them and turn his attention to a higher kind of music.…We were glad to learn from Mr. F. that he intends to devote himself principally hereafter to the production of ‘White-men’s’ music.”

Foster turned out more than 15 songs a year in his salad days of 1850 and 1851, which also saw his marriage to Jane McDowell and the birth of their daughter, Marion. Mostly on the profits of that early industry, he enjoyed an income of more than $15,000 over the decade—very good earnings for an American musician in that era. In the latter half of the 1850s, however, he had published only from one to five songs a year. Nor had he managed his assets wisely, even in the best years, and by 1857, to make ends meet, he was forced to sell all future earnings on virtually his entire catalog.

ONE REASON FOR FOSTER’S ARTISTIC AND FINANCIAL DECLINE may have been the deaths of both parents in 1855 and the subsequent dispersal of his tight family circle, which had always been a source of comfort and inspiration. Another factor may have been his weakness for alcohol, possibly also the cause of a temporary separation from his wife and daughter. But by 1860, Stephen seemed determined to revive his career and possibly his marriage, too. With Jane and Marion, he moved to New York City, home of his principal publisher, Firth, Pond & Company.

They arrived in the fall of 1860, during the political campaign that would result in Lincoln’s election and the subsequent disruption of the Union. Two days after Lincoln’s victory on November 6, Foster applied for a copyright on a new song, “Old Black Joe.” Allegedly inspired by an aged servant of Jane’s family in Pennsylvania, it was reminiscent of Foster’s plantation melodies, though not written in dialect. It was popular, perhaps the last popular song of his lifetime, but his name couldn’t command the earnings it once did. The small family probably lived in a Manhattan boarding house until Jane returned with Marion to Pennsylvania sometime the following year, most likely for financial reasons rather than because of Foster’s alcoholism.

Alone, Foster continued to court his muse. Songs from this period, such as “The Merry, Merry Month of May,” scarcely reflected his descent into rundown Bowery rooming houses. As far as his Union Democrat sympathies permitted, he also attempted to meet the market for war songs. “We live in hard and stirring times,” he wrote shortly after the Battle of Shiloh in early 1862:

Too sad for mirth, too rough for rhymes;…

The rebels thought we would divide,

And Democrats would take their side;

They then would let the Union slide,

And that’s what’s the matter!

“That’s what’s the matter, / The rebels have to scatter,” went the song’s refrain, advertised as “sung…with great success” by Dan Bryant, the minstrel who had recently introduced Dan Emmett’s “Dixie” to the nation.

Shiloh aside, the rebels showed few signs of scattering early in l862, and another Foster song of the period reassured Northerners that “Better Times Are Coming.” Its nine verses read like a roster of Union political and military leaders, from President Lincoln, Secretary of State William H. Seward, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to Union generals Ambrose Burnside and Ulysses S. Grant, and John Ericsson, the inventor of the Union’s first ironclad steamship, the USS Monitor. Foster played no political favorites, devoting verses indiscriminately to former Republican presidential candidate John Frémont and future Democratic nominee George McClellan. Foster’s war songs completely ignored the slavery issue, presenting the war strictly as one to preserve the Union. In “We’ve a Million

in the Field,” he places the blame solely on the South:

We were peaceful hearted in days departed

While faces kept their blighting plans concealed,

But they now must weather

The storms they gather,

For they now must meet a million in the field.

With a number entitled “Was My Brother in the Battle?” Foster managed to combine the genres of war and parlor songs. It essentially mined the same vein of such peacetime songs as “Willie We Have Missed You” and “Lula Is Gone,” but now the missing relative was in the Union army. Seeking word of him from returning soldiers, his sister can only be certain that he was brave and valiant, no matter what his fate. In the wake of the costly Union defeat at Fredericksburg, Foster tried to replicate the spirit of the American Revolution with a sprightly song called “I’m Nothing but a Plain Old Soldier”:

I’m nothing but a plain old soldier,

An old Revolutionary soldier …

And the name of my commander

Was George Washington…

Again the battle song is resounding,

and who’ll bring the trouble to an end?…

You’ve had many Generals from over the land,

You’ve tried one by one and you’re still at a stand,

But when I took the field we had one in command…

IF FOSTER’S PERSONAL FORTUNES REMAINED AT LOW EBB, it wasn’t for lack of industry. He would turn out about a hundred songs—approximately half his lifetime production—during little more than three years in New York. Some of it inevitably was hack work, such as the score or so of hymns he wrote for a publisher of religious music. The hack label would be stuck on most of his secular work of the period, too, parlor and comic numbers along with the war songs. In time, though, much of this later work would be revived and accorded a respected place in the repertoire of 19th-century American art songs.

Details of Foster’s personal circumstances were similarly long obscured under the clouds of popular assumption and myth. Alcohol may have been one of his personal demons, but his productivity argued against his being a drunken derelict. Some of the “eyewitness” accounts fueling his legend were written years later—half a century later in the case of Mrs. Parkhurst Duer, a former employee of one of Foster’s publishers, who wrote in 1916 that the composer had introduced himself to her as “the wreck of Stephen Collins Foster.”

George W. Birdseye, writing three years after the composer’s death, described Foster as “a seedy gentleman who had seen better days,” seated in a barroom in back of a “tumble-down Dutch grocery,” jotting a melody on a sheet of brown wrapping paper. Foster only wrote, according to Birdseye, to acquire means “to indulge his insatiable appetite for liquor.” If so, his thirst must have been monumental, for the record shows that Foster was never busier at his trade.

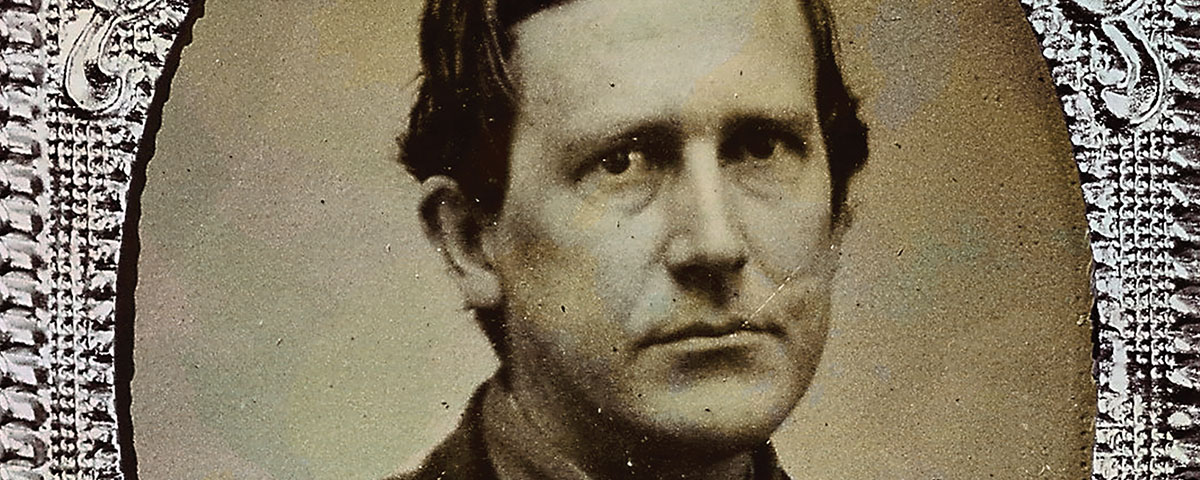

In the only surviving letter from his New York period, Stephen wrote his brother Henry: “I am very well and have been working quite industriously, but pay, these times, especially in music, is very poor.” Jane, working as a telegraph operator back in Pennsylvania, returned at least once to visit, in the summer of 1862, and reported finding him well. An ambrotype of Foster taken in New York shows a respectably dressed, clean shaven, and seemingly self-possessed man. He is pictured with George Cooper, a young poet who became what Foster referred to as “the left wing of the song factory.”

Before he lived in New York, Foster had been his own lyricist. “He said the difficulty of harmonizing sounds with words rendered this necessary,” wrote his brother Morrison, “though he would have often gladly dispensed with the writing of the words if he could.” Apparently, the pressure of boosting his output constrained Foster to do just that, and George Cooper became his most frequent collaborator in his final two years. They produced nearly two dozen joint efforts, including the parlor songs “Jenny June,” “Katy Bell,” and “Kissing in the Dark” and the comic songs “If You’ve Only Got a Moustache” and “There Are Plenty of Fish in the Sea.”

Cooper also provided Foster with several war lyrics. Most of these were in the mother-brother mode, with a war slant: “Willie Has Gone to the War,” “Bring My Brother Back to Me,” and “The Soldier’s Home.” The two men also collaborated on the lighter “Larry’s Good Bye,” in which a recruit promises his Norah that he’ll wed her upon his return—only to have her convince him that they’d better play safe and tie the knot beforehand. A more heavy-handed attempt at humor was “A Soldier in de Colored Brigade.” Written in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation and the North’s ensuing recruitment of African-American soldiers, Cooper and Foster returned to blackface dialect for what one biographer described as “a nasty piece of work.”

Besides feeding lyrics to Foster, Cooper served as a kind of surrogate family. Cooper and others provided Foster with clothes, though the composer was likely to sell them, presumably to provide cash for drink. Cooper testified to Foster’s constant drinking but added that he never saw him intoxicated. He ate little, said Cooper, often dining on no more than an apple or a turnip from the Dutch grocery. Even in better days, according to Morrison Foster, Stephen had always been indifferent to food, satisfied with whatever would appease his hunger. Cooper described similarly spartan living conditions: a cheap lodging house at Number 15 Bowery for 25 cents a night. A slender man, hardly five-and-a-half feet tall, Stephen was constitutionally ill equipped to contend with the adverse conditions of his existence, chief among them his poor diet and living arrangements, his weakness for alcohol, loneliness, and the pressure to produce for scant reward.

Exacerbating these adversities undoubtedly was the war itself, gaining in intensity as it rounded out its third year at the turn of 1864. It was no longer simply a war to save the Union; increasingly, it was a war to end slavery. Foster, who had “enlisted” as a Union Democrat, must have had mixed feelings about the metamorphosis. Two of the lyrics Cooper provided would have had a special appeal to the composer’s war weariness. “My Boy Is Coming from the War” gives two verses to a mother’s anticipation of her son’s homecoming, only to contrast her hopes in the third with the grim news that “on the gory battle plain / Her boy was lying dead!” Eschewing such bathos, and consequently sincerer in expression, was “When This Dreadful War Is Ended”:

Our dear native land’s in danger

And we’ll calmly bide the time

Till this dreadful war is over,

And the bells of peace shall chime.

For Foster, a sadly different bell would toll. On the morning of January 10, 1864, he rose from bed and went to the door of his room to speak to a chambermaid in the hall. He hadn’t been feeling well, and on his way back into the room he stumbled and struck his head against a wash basin. A surgeon was called, as was George Cooper, who arrived to find Foster with an ugly gash on his throat and a bruised forehead. Weakened by fever as well as loss of blood, Foster was taken to Bellevue Hospital, and Cooper wrote Morrison in Cleveland, telling him of Stephen’s condition and his desire to see Morrison. Cooper visited Foster the following two days but on the third was informed that the 37-year-old composer had died. “Stephen is dead,” he now wired Morrison. “Come on.”

Morrison arrived with Jane and Henry Foster. They made arrangements for Stephen’s remains to be returned to Pittsburgh. After the funeral in Trinity Church, the body was taken to Allegheny Cemetery, where a band of some of Pittsburgh’s best musicians awaited the cortège. At the graveside they played such Foster favorites as “Old Folks at Home” and “Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming.”

Hospital records attribute Foster’s death to “injuries accidentally received,” but his weakened condition was at least a contributing factor. In the absence of an inquest, biographers have raised other possible causes of death, such as malaria, tuberculosis, heart attack, or stroke. Maybe something as intangible as war weariness played a role as well. It may not be too great a stretch to count America’s first notable composer as a collateral casualty of the Civil War. MHQ

JOHN VACHA is the author of four books on the history of regional theater and the coauthor of “Behind Bayonets”: The Civil War in Northern Ohio.

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Stephen Foster’s Civil War

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!