In April 1898 the world-famous writer set sail for Cuba to cover the Spanish-American War.

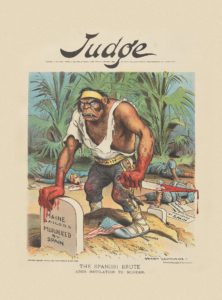

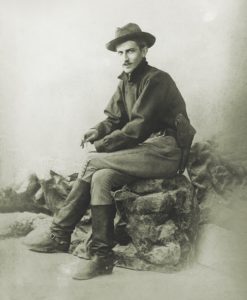

When the Spanish-American War broke out in April 1898, the author of America’s first great war novel had yet to see his nation’s troops in combat. Indeed, with the exception of one frustrating, illness-plagued month as a war correspondent in Greece a year earlier, Stephen Crane had never seen any troops in combat. But the brilliant young author of The Red Badge of Courage, published two years earlier, aimed to change that. With a contract in hand from London-based Blackwood’s Magazine and a verbal commitment from the New York World, Crane set sail for Cuba, where the suspicious explosion of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana Harbor that February had given warmongers in the U.S. Congress and their supporters in the American yellow press the excuse to declare war on Spain, which had ruled Cuba for nearly four centuries. Although the Spanish government maintained that it was blameless for the Maine’s destruction, an investigation by the U.S. Navy concluded that an explosion under the ship’s hull had ignited its gunpowder magazines, suggesting foul play and making war all but inevitable.

Seventeen months earlier, on a similar mission, Crane had nearly died when the steamship he was sailing on, the Commodore, foundered and sank off the Florida coast while en route to Cuba from Jacksonville with a load of guns for Cuban rebels. After 30 wave-tossed hours in a 10-foot dinghy, Crane and his three shipmates swam for safety through the breakers at Daytona Beach. (Ironically, the best swimmer in the lot drowned after being struck on the head by a piece of the dinghy, which broke apart in the heavy surf). The harrowing experience gave Crane the raw material for one his greatest short stories, “The Open Boat,” but it left the rail-thin young writer looking even more cadaverous than usual, and it only strengthened his resolve to get into Cuba. As his novelist friend Joseph Conrad observed: “Nothing could have held him back. He was ready to swim the ocean.”

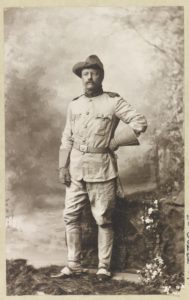

Another, more famous acquaintance of Crane’s was also eager to get to Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy, had been an early and insistent advocate of American intervention in Cuba. When war was declared, Roosevelt resigned his government post and joined U.S. Army Colonel Leonard Wood in forming the elite 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, soon to become famous as the Rough Riders. By the time newly minted lieutenant colonel Roosevelt landed in Cuba at Daiquiri on June 23, Stephen Crane was already there, having come ashore with the 1st Marine Battalion at Guantánamo Bay, on the southeastern tip of Cuba, two weeks earlier.

Given their shared history, Crane and Roosevelt would maintain a discreet distance during the war. Their brief friendship, begun when Roosevelt sent the author a fan letter in 1896, had disintegrated after a well-publicized incident involving Crane, a pretty young prostitute, and the New York City Police Department, of which Roosevelt was then commissioner. The trouble began late one evening in September 1896 when Crane ran into a trio of “showgirls” at a saloon in New York’s infamous Tenderloin district. He was there researching—so he said—a series of articles on the city’s nightlife for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. In the early morning hours of September 16, Crane and the women were walking down Broadway when Charles Becker, a plainclothes policeman, stopped them at the corner of 31st Street. Recognizing one of the women as a well-known prostitute named Dora Clark, the policeman arrested her for soliciting. (She had been hauled in on similar charges four times that same month.) Crane loudly protested the arrest, and a judge dismissed the charges against Clark after Crane testified on her behalf.

Trading on his nascent friendship with Roosevelt, Crane sent the commissioner a telegram condemning the arrest. But if he expected Roosevelt to take his side, Crane was sorely mistaken. Roosevelt had recently conducted a series of celebrated “night patrols” through the Tenderloin, and he knew all too well the sordid nature of the district. He stood by Becker’s account of the incident. When Crane repeated his testimony at a wrongful-arrest hearing, the fledgling Crane–Roosevelt relationship abruptly dissolved. “He wasn’t gathering any data,” Roosevelt said of Crane. “He was a man of bad character and he was simply consorting with loose women.” Whatever happened that night, Crane was ultimately proved right about Becker. Nineteen years later Becker would become the first American policeman to die in the electric chair after being convicted of arranging the contract murder of small-time New York gambler Herman “Beansie” Rosenthal to cover up Becker’s loan sharking activities.

Crane had gotten his first, long-awaited view of Americans in combat even before Roosevelt reached Cuba. In their base camp at Guantánamo, unwary U.S. Marines were ambushed by Spanish guerrillas. Crane spent a long night crouched in a trench with four marines as bullets zipped over their heads from the nearby jungle. He was convinced that “all Spain was shooting at him.” The Spaniards missed Crane but hit one of his companions, navy surgeon John Blair Gibbs, who was struck in the forehead as he stood outside his medical tent, after mordantly joking, “Well, I don’t want to die in this place.” The fatally wounded Gibbs was dragged into Crane’s ditch; in the darkness, Crane at first did not realize who it was. “I heard somebody dying near me,” he would write in a dispatch. “He was dying hard. Hard. It took him a long time to die. He breathed as all noble machinery breathes when it is making its gallant strife against breaking, breaking. But he was going to break.” Gibbs’s final agony wore on Crane’s nerves. “I thought this man would never die,” Crane later admitted. “I wanted him to die.”

Three days later Crane accompanied a detachment of 160 marines and 50 Cuban insurgents to Cuzco, six miles down the coast, to capture the only water well in the area. Captain George Elliott offered to let Crane serve as his aide during the mission, and Crane accepted. Crane confessed later that he was “bitterly afraid” during the fight at Cuzco. His heart, he said, was “in his boots” and he was “cursing the day that saw me landed on the shore of the tragic isle.” Nevertheless, he carried dozens of messages to and from Elliott, marveling all the while at how cool the marines were under fire. Sergeant John H. Quick, in particular, won Crane’s admiration by calmly signaling for artillery fire from an offshore warship. With his back to the enemy, Quick directed the fire using a handkerchief tied to a long stick. “I watched his face, and it was as grave and serene as that of a man writing in his own library,” Crane reported. “He was the very embodiment of tranquility.” Quick was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. Crane, a civilian, received no such medals, but Elliott cited him afterward for his “material aid in the action.” Other marine officers also praised Crane’s bravery under fire.

Crane performed another unofficial service for the American forces when he and fellow New York World correspondent Sylvester Scovel rode nine miles by horseback up 2,000-foot Mount St. Augustin, overlooking Santiago Harbor, to spy on the Spanish fleet hiding there. It took them a lot of “dodging and badgering and botheration,” as Crane put it, to make it up the mountainside, but the arduous journey was worth it. The entire Spanish fleet lay below, and the summit, with its clear mountain air, “was the kind of country in which commercial physicians love to establish sanitariums.” They took the valuable information to Rear Admiral William T. Sampson aboard his flagship New York. Armed with the new intelligence, Sampson and Major General William R. Shafter, the U.S. Army commander, devised a plan to land 16,000 troops 18 miles east of Santiago at Daiquiri, safely out of reach of the Spanish fleet.

The spying effort took a toll on Crane, who perhaps was already harboring a fatal case of tuberculosis. Back aboard ship, exhausted, he wrote, “I discovered that I was a dead man. The nervous force having evaporated, I was a mere corpse. My spinal cord burned within me as if it were a red hot wire.” Doctors diagnosed yellow fever, which was already rampant among the American troops in Cuba, but then told him he was suffering from a less deadly case of malaria. Refusing to take to his bed, Crane joined other correspondents in observing the American landing at Daiquiri on June 22–23.

The next day they proceeded to Siboney, seven miles west, where Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and elements of the 1st and 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiments had begun heading inland on foot to Las

Guasimas, a mountain pass where Spanish forces were waiting in ambush. Crane and a number of other reporters, including Ernest McCready of the New York World, Edward Marshall of the New York Journal, and Burr McIntosh of Leslie’s Weekly, followed the troops up the steep mountain trail, which was littered with blankets, jackets, tents, and supplies that the heat-plagued American troops had discarded. At the front of the line Marshall joined Roosevelt and the colonel’s favorite correspondent, Richard Harding Davis. Crane remained in the rear, preferring to avoid Roosevelt at all costs.

The Rough Riders continued thrashing through the woods and brush, “making more noise than a train going through a tunnel,” Crane later wrote. With the extra two weeks in-country, Crane was able to recognize “the beautiful coo of the Cuban wood-dove” for what it really was—“the Spanish guerilla wood-dove which had presaged the death of gallant marines” at Cuzco. He was right. No sooner had a sergeant ordered the men to stop talking than a volley of fire erupted from the tree line. The Spanish were firing German-made Mauser rifles, whose deadly dumdum bullets, Crane wrote, “sounded as if one string of a most delicate musical instrument had been touched by the wind into a long, faint note, or that overhead someone had swiftly swung a long, thin-lashed whip.” The smokeless powder the Spanish used made it impossible to tell where they were firing from. The Rough Riders, to their credit, charged across open ground in the face of point-blank fire, sending the Spanish into retreat. The impetuous charge, Crane reported, “by any soldierly standard, was magnificent.”

Roosevelt claimed victory, even though the Spanish were under orders to withdraw to Santiago anyway. Eight Rough Riders were killed, including Captain Allyn Capron and Sergeant Hamilton Fish II, the grandson of former secretary of state Hamilton Fish. Crane’s account disputed Roosevelt’s triumphant claims. Under the headline “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders’ Loss Due to a Gallant Blunder,” Crane criticized the troops—though not Roosevelt directly—for ignoring warnings from their Cuban scouts, talking too loudly, marching too noisily, and failing to recognize the cooing sounds of the impending Spanish ambush.

In his own account, published a year later, Roosevelt struck back with pointed sarcasm implicitly aimed at Crane. “I did not see any sign among the fighting men, whether wounded or unwounded, of the very complicated emotions assigned to their kind by some of the realistic modern novelists who have written about battles,” Roosevelt wrote. “There was doubtless a good deal of panic and confusion in the rear where the wounded, the stragglers, a few of the packers, and two or three newspaper correspondents were, and in consequence the first reports sent back to the coast were of a most alarming character, describing, with minute inaccuracy, how we had run into an ambush, etc.” But even Richard Harding Davis, the reliably pro-Roosevelt correspondent, later admitted that the Rough Riders had indeed “blundered into an ambuscade” at Las Guasimas.

Crane encountered other criticism, not entirely unfounded, from his superiors at the New York World for coming to the aid of his wounded friend and colleague Edward Marshall of the rival New York Journal. Crane was sitting in the rear smoking a pipe when a soldier rushed up to tell him, “There’s a correspondent up there shot all to hell.” The soldier led him to Marshall, who had been shot in the back, close to his spine. Crane was especially upset because Marshall had been one of the earliest and most generous supporters of The Red Badge of Courage. “Hello, Marshall,” he said, trying to be upbeat. “In hard luck, old man?”

“Yes, I’m done for,” Marshall said.

“Nonsense,” Crane replied. “You’re all right, old boy. What can I do for you?” Marshall asked Crane to file his report of the battle—after he had filed his own. Crane then walked three miles through the 100-degree heat to Siboney, where he cabled Marshall’s dispatch to the Journal, found a stretcher (they were in short supply), and slogged three miles back to the front. Marshall, who survived but lost a leg and was paralyzed below the waist for the rest of his life, never forgot Crane’s kindness. “He was probably as tired then as a man could be and still walk,” Marshall later recalled. “But he trudged back from the coast to the field hospital where I was lying and saw to it that I was properly conveyed to the coast.” Crane’s editors at the World were less appreciative, particularly since he had sent off Marshall’s report before bothering to send his own.

Still suffering from malaria, Crane remained with the army and a week later witnessed one of the most famous charges in American history, one led by Theodore Roosevelt. The American high command had decided to take Santiago by seizing the high ridge of hills overlooking the city. On July 1 the assault got underway when Brigadier General Henry Lawton’s 2nd Division of regular infantry attacked the fortified village of El Caney. They met stiff resistance, which delayed the planned assault by the rest of the infantry and dismounted cavalry on San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill, a mile and a half southwest. Roosevelt, now in command of the 1st Cavalry after Leonard Wood had been promoted to general, waited impatiently while the Regulars began attacking San Juan Hill on the extreme south. In the meantime, the Rough Riders suffered equally from Spanish shrapnel, hunger, thirst, and the infernal heat. Finally, at 1 p.m., Roosevelt received verbal confirmation to assault Kettle Hill. Leaping onto his horse, he led his dismounted troops up the steep hillside in the face of intense rifle fire. It was, he said later, the start of his “crowded hour.” For others, it was the last hour of their lives.

Richard Harding Davis, observing the American assault, saw “a thin blue line that kept creeping higher and higher up the hill. It was inevitable as the rising tide. It was a miracle of self-sacrifice, a triumph of bulldog courage, which one watched with breathless wonder.” Crane joined Harding in watching the attack. The green hills of San Juan reminded him of the orchards in his boyhood home in Orange County, New Jersey. “Then somebody yelled: ‘By God, there go our boys up the hill!’ ” he wrote. “There is many a good American who would give an arm to get the thrill of patriotic insanity that coursed through us when we heard that yell. Yes, they were going up the hill, up the hill. It was the best moment of anybody’s life.”

Against all odds, Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and the Regulars carried the heights. At the summit, Roosevelt shot and killed a fleeing Spanish soldier. “He doubled up like a jackrabbit,” Roosevelt proudly told a friend afterward. Crane commandeered a pinto pony and cantered toward San Juan Hill wearing “a gleaming white raincoat” that made him “a shining target,” in the words of fellow journalist Jimmy Hare, who urged him to dismount. “If they aim at me, so much the better,” Crane replied. “No Spaniard ever hits the thing he aims at.”

At the foot of the hill, Crane dismounted when he came across a group of wounded Americans at a field dressing station. He and Hare saw “a hundred broken men, the human wreckage brought from a few square yards of the battlefield.” One of the casualties, remarkably, was a former classmate of Crane’s from Claverack College, a military academy in New York’s Hudson River Valley. Corporal Reuben McNab of the 71st New York Volunteers had suffered a bullet wound to the chest, and the sight of his badly wounded classmate brought the war home to Crane in a way that nothing else had: “The apparition of Reuben McNab, the schoolmate lying there in the mud with a hole through his lung, awed me into stutterings, set me trembling with a sense of terrible intimacy with this war which heretofore I could have believed was a dream.” Crane gave McNab his pony to ride back to Siboney. “If you’re goin’ by the hospital, step in and see me,” McNab responded with Crane-like sangfroid. McNab survived his wounding and was honorably discharged after returning to New York.

Later that afternoon Crane made a memorable reappearance at the front, striding casually along the crest of San Juan Hill in his white raincoat, smoking a pipe, as Mauser bullets zinged by. General Wood himself shouted for Crane to get down. “You’re drawing fire on these men,” he said. Crane pretended not to hear him. Davis, who

admired Crane’s writing, disliked Crane as a person; still, he didn’t want to see him killed. “You’re not impressing anyone by doing that, Crane,” he called out. Crane instantly dropped to the ground and crawled back. “I knew that would fetch you,” Davis said. Crane grinned. “Oh, was that it?” he said. Bragdon Smith, a journalist with the New York Journal, witnessed another instance of Crane’s near-suicidal coolness under fire. Smith reported seeing Crane standing calmly under a tree while bullets sheared off its leaves and struck several men standing nearby. Crane, unperturbed, “finished rolling his cigarette and smoked it without moving from the spot where the bullets had suddenly become so thick,” Smith would later write.

A week later, suffering from a renewed onslaught of malaria, Crane was invalided out of Cuba aboard the hospital ship City of Washington. Again told he had yellow fever, Crane was ordered to stay away from the other sick and wounded soldiers; he spent the next five days and nights lying on deck alone, shivering beneath a little rug. As a civilian, Crane was allowed to recuperate at the luxurious Chamberlain Hotel in Old Point Comfort, Virginia, opposite Fort Monroe. Falsely accused by an embittered colleague of writing an unsigned article indicting officers of the 71st New York for cowardice under fire at San Juan Hill (the article, apparently accurate, was actually written by Sylvester Scovel), Crane was fired by the New York World. He managed to get off one last shot, however indirect, at Roosevelt and his much-lionized Rough Riders.

In “Regulars Get No Glory,” Crane singled out for praise the humble enlisted men at San Juan Hill. Instead of gloating over “the gallantry of Reginald Marmaduke Maurice Montmorenci Sturtevant, and for good goodness sake how the poor old chappy endures that dreadful hard-tack and bacon,” Crane scoffed, the press should have focused on common soldiers such as “Michael Nolan, the sweating, swearing, overloaded, hungry, thirsty, sleepless Nolan, tearing his breeches on the barbed wire entanglements, wallowing through the muddy fords, pursuing his way through the stiletto-pointed thickets, climbing the fire-crowned hill.” As always, the writer’s sympathies were with the little man, not with such well-born elites as Theodore Roosevelt and his socialite friends.

Roosevelt did not respond to Crane’s final riposte, but his own account of the war, The Rough Riders, published a year later, was so self-aggrandizing that the humorist Peter Finley Dunne joked that it should have been named Alone in Cuba. After the war Roosevelt and Crane never laid eyes on each other again—no doubt much to their mutual relief. Crane died two years later of tuberculosis. Roosevelt, of course, followed a different arc, helped immeasurably by the “crowded hour” that he and Crane had shared one breathlessly hot July afternoon at San Juan Hill. MHQ

Roy Morris Jr. lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He is the author of nine books, including, most recently, Gertrude Stein Has Arrived: The Homecoming of a Literary Legend (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | Stephen Crane at the Front

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!