Photographer Mathew Brady reached Gettysburg nearly two weeks after the battle ended 150 years ago this summer, forcing him to make decisions about what to photograph that he might not have made had he arrived sooner. His former protégés and now competitors, Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan and James F. Gibson, had easily beaten him there, arriving just two days after the fighting stopped, when the chaos of the battle was still very much in evidence, most dramatically in the form of unburied bodies.

Gardner and Gibson, while still working for Brady’s Washington gallery, had been the first photographers to make images of the dead of war, at Antietam the previous September. Brady had shown those searing pictures, taken in stereoscope or what we call 3-D, at his gallery in New York to some notice and acclaim. Now working for the studio that Gardner and his brother had started in the meantime, the two men and O’Sullivan once again focused their cameras on the lifeless bodies—even, famously or infamously, moving one of them to create a more effective composition.

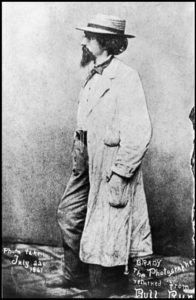

Gettysburg was the first battlefield Brady had seen since the war’s opening clash at Bull Run, where he had tried to make photographs but lost his glass negatives and all his equipment in the frenzied retreat of the Union army. When approaching Gettysburg from Washington, Brady’s assistants had run into Gardner, so when Brady arrived he knew that Gardner had preceded him to the scene. By this time most of the bodies had been buried, and the landscape had, for the most part, regained its rural placidity.

The delayed arrival worked to Brady’s advantage. Gardner got the scoop and got the bodies, but Brady’s photographs show a firmer sense of the battlefield’s important sites and reflect the growing public understanding of what had happened there. As photos, they were also far superior to Gardner’s. David Woodbury and Anthony Berger, Brady’s assistants from Washington, had made good use of a week or so waiting for their boss to arrive, familiarizing themselves with the town and battlefield. The metaphorical fog of war had begun to lift in the first days after Gardner left around July 7, as newspaper accounts became more detailed and more accurate. By the time Brady set off from New York, he had a good understanding of the battle’s contours and its most important figures, information he could augment with the local knowledge Woodbury and Berger had been gathering.

Brady and his men took 36 photographs in the time they spent there, estimated to be between three days and a week. Brady himself appears in at least six of the images, and so do his assistants. He and two of them appear together in the distance in one photograph, meaning that a third assistant was also on hand.

One of the subjects they focused on shows Brady’s familiarity with the news of the battle. Among the first Union soldiers killed, on the morning of the first day, was the highest-ranking officer to die there, Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, who commanded the Army of the Potomac’s left wing as the battle began. A cavalry division under his command had dismounted and fought the first real engagement at Gettysburg, and Reynolds had brought up and positioned two infantry corps when he was shot from his horse, possibly by a Rebel sharpshooter. A Pennsylvanian who had gone to West Point and fought in the Mexican War, Reynolds was thought by many to be the best general in the Union Army. The first newspaper reports, as early as July 3, mentioned Reynolds’ death, and three of Brady’s photos, in each of which Brady himself appears, are connected with this signal event.

One photo shows a pond in th

e foreground, beyond which Brady stands alone before a split-rail fence, on the far side of what was erroneously called “The Wheat-Field in Which General Reynolds Was Shot.” Another photo bears a similar caption. In it, Brady stands to the right with an assistant who points to woods to the right of them— where Reynolds was in fact shot. The third photo shows, as a woodcut based on it appearing in the August 22 Harper’s Weekly put it, “the barn to which [Gen. Reynolds] was carried, where he breathed his last moments, etc.” That “etc.” seems a little unfeeling to us today, but in reality the barn was near enough where Reynolds fell to have been a plausible place for him to be taken—except that Reynolds died instantly, and his body was carried to a house south of town. In this photo, as in the other two, Brady stands in the middle distance, wearing a dark coat and a round light-colored hat with a dark band. In all three, his back is to the camera, so the viewer is looking over his shoulder.

These photos introduce in an explicit way a human consciousness of the violence that had played out in these fields. We see one or two people contemplating the placid landscape, and we know what must be on their minds: the turmoil and death that filled these scenes only days before. Even now we can sense the drama of the battle that unfolded there, if only in the thoughts of Brady and his colleague. All photos imply the presence of a human viewer, of course—the person who points the camera. But more directly, perhaps, than had yet been done in this medium, Brady has offered what might be called first-person photography, a statement that a photo is not just an objective rendering of a scene—the work of the sun, as it was often called in photography’s first decades—but a view created, in effect, by an individual consciousness.

Brady the photographer, shown contemplating the scene of the fighting, reflects and makes obvious the work of the operator standing behind the camera. Even if putting himself in front of the camera was merely an act of promotion (self-promotion being inseparable from promotion of the Brady brand and business), it is hard not to admire the audacity of what he has done. No dead men appear in any of his Gettysburg photos, and only one dead horse, but in their psychological pointedness his images are more intense than any of Gardner’s gruesome pictures. These Brady photos question the main argument that photography claimed as an improvement upon painting and drawing—its scientific objectivity. They steal photography from the sun.

Has Brady done anything more than borrow a technique from journalism, and at least indirectly from literature? Does asking how we can tell the photographer from the photograph make these images works of art? Brady at times wished to be taken seriously as an artist. The three Reynolds photos qualify as works of art in that they have a clear idea behind them and are executed in a way that enhances that idea. In each image Brady has posed himself close enough to the camera to be a focal point but far enough away to be less than the whole subject. We always see his back, which makes him in one sense anonymous, allowing him to stand in for every viewer, yet his hat and the hat of the assistant who appears in two images are so distinctive as to particularize them. This is not “Man Standing in Field”; even without knowing that this was Brady himself, the viewer would know this is a distinct individual contemplating the horrible scenes that had taken place within the camera’s view.

Robert Wilson’s biography Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, from which this article was adapted, will be published in August.

Originally published in the August 2013 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.