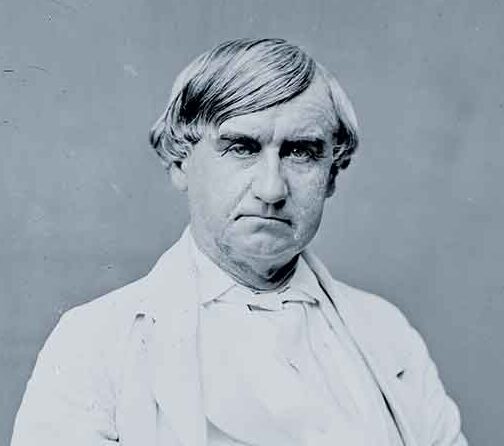

Then Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton called Joseph Holt into his office on July 18, 1862, it was almost certainly to offer him a powerful post that had just been authorized at the War Department. The previous day President Abraham Lincoln had signed legislation creating the new office of judge advocate general, the nominal function of which would be to review army courts-martial. To that duty Stanton would add some interesting assignments of a more political nature. Holt was interested, but before recommending him for appointment Stanton would have to exercise some suasion on the president, who already had someone else in mind.

Brevet Major John F. Lee, one of Robert E. Lee’s many loyal cousins, had served as judge advocate for the U.S. Army since 1849, reviewing court-martial findings and offering legal recommendations to five presidents. Major Lee was a brother-in-law of Lincoln’s postmaster general, Montgomery Blair, whose entire family expected Lee to get the expanded office. Blair later confirmed that the post had been created for Lee, and had been promised to him. Lee, however, was a conservative. He championed nonpartisan justice and disliked the idea of using military courts to prosecute civilians. As Stanton could have predicted, Holt would readily subordinate justice to politics, and he quickly became an enthusiastic advocate of military tribunals, which provided a more certain means of obtaining convictions.

Stanton knew Holt from having served with him in President James Buchanan’s Cabinet, where Stanton served as attorney general during the last weeks of Buchanan’s term. Holt, a sometimes lawyer and Democratic activist from Kentucky, had run into such financial straits by the age of 50 that his wife begged her brother to take Holt into his law firm to give him an income. At the same time, Holt solicited a government post through Democratic friends, and in September 1857 he accepted the office of patent commissioner after initially scorning it for its “small salary” and relative obscurity. Never again would he be employed outside the federal government. When Buchanan’s postmaster general died in March 1859, Holt moved into to that vacancy, and in the waning days of 1860 he became secretary of war.

Holt, who was growing stout when he came to Washington, brought with him a longstanding habit of cultivating clandestine extramarital relationships. His wife, Margaret, was suffering from what appears to have been tuberculosis, and he often lived apart from her. Sometime in 1858, Holt lodged her in her sister’s home in Frederick, Md., and that allowed him more time for the attention of women whom he had given employment in the Patent Office. Their letters to him began just before Margaret moved to Frederick, and during her absence Holt took the opportunity to engage one young lady in a flirtation—or something more—that lasted for most of a year.

As in a previous affair of his, the letters that document this one were all written in French, and they drip with passion. “Come[,] come… oh come,” wrote the woman who alternately signed herself “Amelie,” “Aglai Lapsley,” and “Darling.” She wrote once that “I await you with impatience,” and when he failed her in a rendezvous she chastised him as “cruel.” Often she assured him that she was all his, declaring herself “your Darling, who loves and thinks of no one but you.” Holt evidently supplied her with franked envelopes for their correspondence, but he wore the mask of an honest public servant with Margaret, who had to stamp the letters in which she pleaded for permission to visit him.

Holt began neglecting his paramour toward the end of 1859, as Margaret entered the final stages of her illness. He addressed his wife as “My precious Maggie,” and throughout the dalliance he indignantly dismissed her hinted suspicions with assurances that he was unflinchingly faithful to her. Judging by his correspondence from other women, including at least one who was obviously married, Margaret’s death in the summer of 1860 did not end Holt’s fondness for covert liaisons.

The duplicity Holt showed his wife carried into his public service, as did his tendency for angry denials of improbity in one controversy after another, most of which involved suspiciously similar circumstances. Those traits made him an excellent match for Edwin Stanton, perhaps the most deceitful man in Lincoln’s Cabinet, who immediately went to work on changing the president’s mind about Major Lee. Within a week, Lee’s family knew that Stanton did not want the conservative major, who later learned that Stanton had carried malicious tales about him to Lincoln.

Both Holt and Stanton had come out of the Buchanan administration with reputations as conservative Democrats. Holt, for example, had defended the legality of slave-state laws against mailing abolition literature, and both men had supported John Breckinridge for president in 1860. As Radical Republicans gained strength, Stanton reversed course, abruptly siding with them in their war against George B. McClellan and conservative generals like him. By the summer of 1862, Holt had made the same metamorphosis. That made Stanton all the more anxious to have Holt sitting as the Army’s chief legal officer when an opportunity presented itself to court-martial McClellan and some of his favorite subordinates.

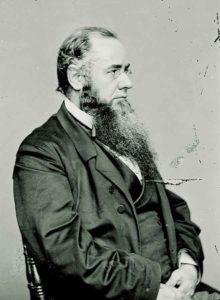

General in Chief Henry Halleck had ordered McClellan’s army back from the Virginia Peninsula early in August 1862, and on August 28 Stanton formally asked Halleck if he thought that order had been obeyed as promptly as “the national safety required.” The question foreshadowed a court-martial, and over the next 72 hours Stanton strove mightily to persuade the rest of the Cabinet to sign a petition for the president to remove McClellan from command. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John Pope, commander of the newly created Army of Virginia, had lost the Second Battle of Bull Run, in which McClellan’s Army of the Potomac comrade and confidant Fitz John Porter had participated. By the time Pope reached Washington on September 3, he was blaming Porter for the defeat. That same day, Stanton finally succeeded in convincing Lincoln to appoint Holt as judge advocate general, prompting the understandably offended Lee to resign from the Army.

Lincoln stymied Stanton’s plans for removing McClellan when the president permitted Army of the Potomac regiments sent to the Army of Virginia to return to the general’s command, and then take the field under McClellan in the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia as it moved into Maryland. But by September 5 Stanton used Pope’s complaints to order a court of inquiry into Porter’s alleged conduct at Bull Run. That also had to wait until November, when Lincoln removed McClellan from command.

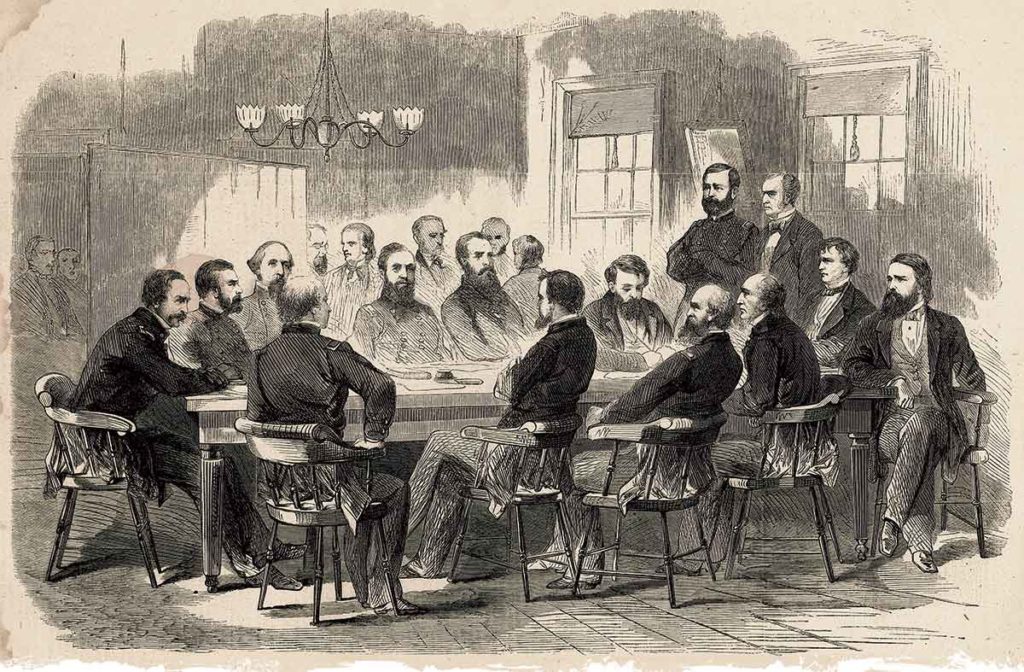

Then the team of Stanton and Holt immediately pounced on Porter. Stanton appointed a court-martial heavily weighted with generals hostile to the McClellan clique or to Democrats in general, and he named the most hostile of them as president. Two of the judges bore some military responsibility in the defeat for which Porter was blamed, and one of them acted as a witness against the defendant. Holt took the prosecutorial role that would normally have gone to one of his subordinate judge advocates. Stanton also took the unprecedented step of ordering the court to hurry the process once the prosecution had concluded its case, thus cutting the defense short. Nevertheless, journalists and other spectators who heard the testimony expected acquittal, but Holt was so certain of his judges’ bias that he did not even deliver a summation. The verdict of Porter’s guilt surprised all who had expected impartiality.

The president would have to approve the result. To be certain that he would do so, Stanton prepared an order removing Porter for the president to sign before even receiving the record of the trial. He also called on Holt to summarize the proceedings and report on any potential legal questions. Holt ignored all legal improprieties that had occurred, such as having a hostile witness serve as a judge and Stanton’s order curtailing the defense’s presentation. His summary consisted only of the final prosecution argument he had foregone delivering in court. He included none of the testimony that contradicted the charges against Porter, and he cast those charges as virtually unquestionable. Lincoln—who was known to intervene in the cases of contractors convicted of fraud and second lieutenants cashiered for absence without leave—dishonorably dismissed Porter solely on the basis of Holt’s deliberately jaundiced “review.”

Holt then went further in his chosen role as a propagandist. He took his one-sided review to a private printer, personally examining the proofs before it was published in pamphlet form for mass distribution. Bundles of that indictment were delivered to officers in the Army and to the public, eliciting contempt even among those of Porter’s old acquaintances who knew nothing of the political intrigue behind his downfall. The disgraced general petitioned to have the entire record of the trial published, including the defense testimony and argument, but that request was not granted.

To reward Holt for performing as expected, Stanton asked the president to submit the new judge advocate general’s name to the Senate on January 19, 1863—the day Holt submitted his hatchet job on Porter. The Senate confirmed his appointment in February, affording him a lucrative sinecure that he retained until his retirement 13 years later.

Stanton never had cause to regret his choice of Holt, whose review process gave a semblance of judicial propriety to the practice of War Department orders for civilian arrests, which Stanton had just begun to escalate. The new judge advocate general immediately began routinely approving those arrests, most of which involved nothing more criminal than dissident political speech. Less than a week into his tenure, Holt looked into the case of an elderly New Hampshire physician imprisoned for accusing volunteers of harboring more interest in the generous new enlistment bounties than in their country. Holt concluded that if any crime deserved arrest, it was the doctor’s.

The results of Holt’s reviews were so inconsistent, they seemed altogether arbitrary. On the president’s broad hint, only a week after submitting the biased screed that had ruined Porter’s life, Holt recommended remitting far lighter punishment of a much less competent officer, who against orders had initiated a losing battle. For that offense Henry Benham, a Regular Army major and volunteer brigadier, had had his volunteer commission revoked. With incredible hypocrisy, Holt deemed that as unfair to a man “who has now given twenty-five years of his life to his country.” Not only was Benham reinstated, he was given command of the Army of the Potomac’s Engineer Brigade. Three months later, he had to be temporarily removed from the field during the Chancellorsville Campaign, where his drunken bellowing threatened to reveal a secret bridging operation of the Rappahannock River by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick.

The Porter case made it obvious that Holt’s opinion could redeem or destroy a defendant’s future. It would be remarkable if that enormous power failed to elicit some form of bribe offer among the many thousands of cases he was supposed to review, but if he reported any such offer, the complaint has not yet come to light. Unlike many of his counterparts in federal office, however, Holt saw his fortunes improve dramatically from the pecuniary embarrassment of 1857. In 1860, when median wealth in Washington, D.C., came to only $100 and the average estate amounted to $1,913, Holt claimed $88,000—all but $8,000 of which was in the form of personal property that would include cash and bonds. By 1870, he was worth $155,000.

Holt reprised his role in a replay of the Porter inquisition when Stanton set out to install a favorite in place of his infuriatingly independent surgeon general, William Hammond. Stanton convened a court composed of his political allies and personal friends, aged officers unsympathetic to the upstart Hammond, and a couple of generals who needed to work their way out from under a cloud. That panel obligingly convicted Hammond of accusations that ranged from picayune to perfectly false, whereupon Holt went to work as before, doctoring his review for the president to avoid exculpatory evidence or testimony. He possibly even removed Hammond’s defense statement from the court record, lest the president ask for the complete record, for that remains the only missing part of the document today. Then, having once again obtained Lincoln’s approval for the dishonorable dismissal of a Stanton victim, Holt subjected Hammond to public disgrace, as he had Porter. In another pamphlet published at War Department expense, he detailed only the prosecution’s case—including charges and specifications on which Hammond had been found innocent, as though he had been convicted of those as well. In a typographical “error” that survived his proofreading, he added two zeroes to an amount of disputed medical costs, implying that Hammond had been accused of misusing $3,531,400 instead of $35,414.

With the presidential election looming in 1864, Stanton sent Holt on a junket that allowed him a vacation at his Kentucky home on the pretext of “investigating” subversive activities in the West. The investigation consisted of little more than picking up documents designed to discredit the Democratic Party as a network of treasonable conspirators. Brigadier General Henry Carrington, who had contributed to the Republican recovery of 1863 with similar propaganda about Copperhead intrigues in and around Indiana, had collected another trove of incriminating material. In St. Louis, Colonel John Sanderson did the same in interviews with characters of notorious reputation, and he accepted as gospel a host of preposterous allegations that he said had been submitted anonymously, by mail.

Holt brought that imaginative literature back to Washington, gathering it in a “report” that Stanton published four weeks before the election and disseminated nationwide. To buttress such claims, Holt’s subordinate judge advocates conspicuously prosecuted a handful of accused conspirators in trials followed daily by the press. In each instance, the prosecutors kept a cavalcade of government witnesses on the stand until after the election, to avoid the publication of any rebuttal by defense witnesses until the primary object of the trials had been achieved.

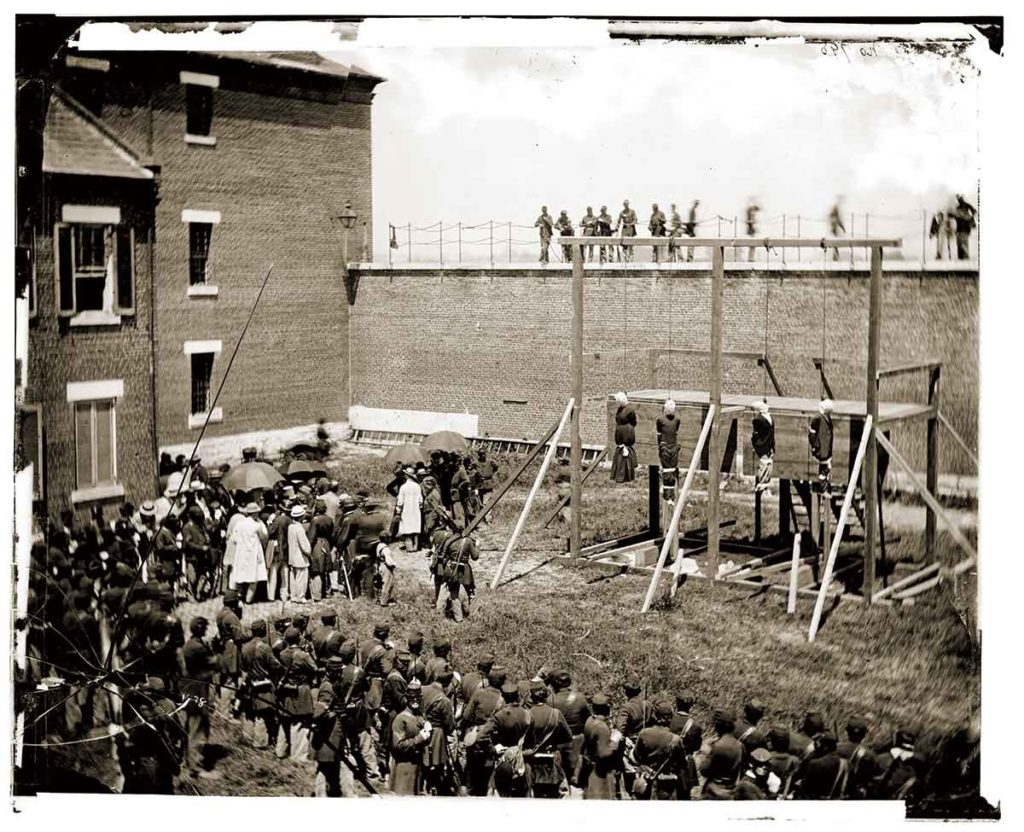

With the end of the war, Holt grew even bolder at manipulating the judicial process. Stanton made sure that Holt’s bureau oversaw the trial of the Lincoln conspirators, and it was Holt who took the trial record to President Andrew Johnson for approval of the death sentences. Johnson was in bed at the time, quite ill. Two years later, when the court’s recommendation for mercy to Mary Surratt was mentioned in news about her son’s trial, Johnson said he had never seen it. In curiously awkward phrasing, Holt insisted that he had pointed out the document, and he spent years soliciting testimonials purportedly supporting his claim, publishing them as the Vindication of Hon. Joseph Holt. Holt had nonetheless habitually withheld anything from Abraham Lincoln that might have been favorable to a defendant, and he also omitted the clemency petition when he had the court record published.

A historian who found the clemency plea attached to the court record in the 1920s concluded that it had been bound with the record, torn out, and then reinserted. The surviving microfilm comports with that interpretation.

In his and Stanton’s zeal to connect the assassins to the Confederate government, Holt retained a professional con artist known sometimes as Sandford Conover to provide witnesses willing to perjure themselves. Major General John Dix had already warned how dishonest Conover was, but Holt spent another year seeking Conover’s assistance. When a congressional committee summoned Holt to explain why he was colluding with such a rascal, Holt fell back on a defense of ignorance, claiming that Conover had duped him completely. That controversy produced another of Holt’s self-exculpating pamphlets, this time titled Vindication of Judge Advocate General Holt, from the Foul Slanders of Traitors, Confessed Perjurors and Suborners, Acting in the Interest of Jefferson Davis.

None of that stopped Holt from recommending, a year later, that President Johnson pardon Conover, who had been sentenced to 10 years in prison for perjury. In his recommendation, Holt claimed that Conover had contributed materially to the prosecution of John Surratt, which was not at all true. Instead, Holt and Radical Republican Congressman James Ashley hoped that Conover’s pardon would persuade him to offer testimony, or witnesses, who might connect President Johnson himself to Lincoln’s assassination. Conover’s wife provided the White House with correspondence on that intrigue, including a script of the desired testimony in the handwriting of a clerk from the House Judiciary Committee, which was considering impeachment.

The power of Holt’s Bureau of Military Justice waned sharply when the Supreme Court ruled his military tribunals unconstitutional. After Stanton left the War Department, Holt was forced to abandon his politically motivated investigations, reverting to the mundane duty of judicial review for which his post had nominally been created. Late in 1875, he finally retired on an Army pension at the rank of brigadier general.

He spent his remaining years in idle comfort in Washington, stirring occasionally to refute the reputation for skullduggery he had developed under Stanton. That pair had always confirmed each other’s virtue in every scandal. When Stanton was suspected of removing the missing pages from John Wilkes Booth’s diary, Holt asserted it was “absolutely certain” that he had not—although, as the last person to come into possession of it, Holt had no way of knowing. When Holt sought to be exonerated from complicity in the Conover affair, Stanton dismissed the imputations on Holt’s character as “entirely groundless.” Holt nevertheless turned on Stanton after he died, allying with another Radical colleague to accuse the late war minister of suppressing testimony that Holt had shown President Johnson Mrs. Surratt’s clemency petition.

The 87-year-old Holt died on August 1, 1894, at his Washington home on the corner of C Street and New Jersey Avenue. In an ironic historical twist, four blocks away, near Seward Square, Anna Hoover was then pregnant with a child she would name John Edgar. Thirty years later Mrs. Hoover’s son would take charge of an agency not unlike the one Joseph Holt had headed in the 1860s, and he would rule it with a similar ethic.

Historical iconoclast William Marvel is the author of numerous books, including A Place Called Appomattox: Community at the Crossroads of History, Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton, and most recently, Lincoln’s Mercenaries: Economic Motivation Among Union Soldiers in the Civil War, which will be released in November 2018 by LSU Press. He lives in New Hampshire.