In 1138, as rival factions staked claim to the English crown, the English and the Scots engaged in a fierce clash in the marshy reaches of Northallerton, North Yorkshire. While the opposing forces grappled on the battlefield, amid the English lines rose an unusual totem comprising a wooden mast, a dangling silver box and sacred banners—a standard the English hoped would bring them divine assistance.

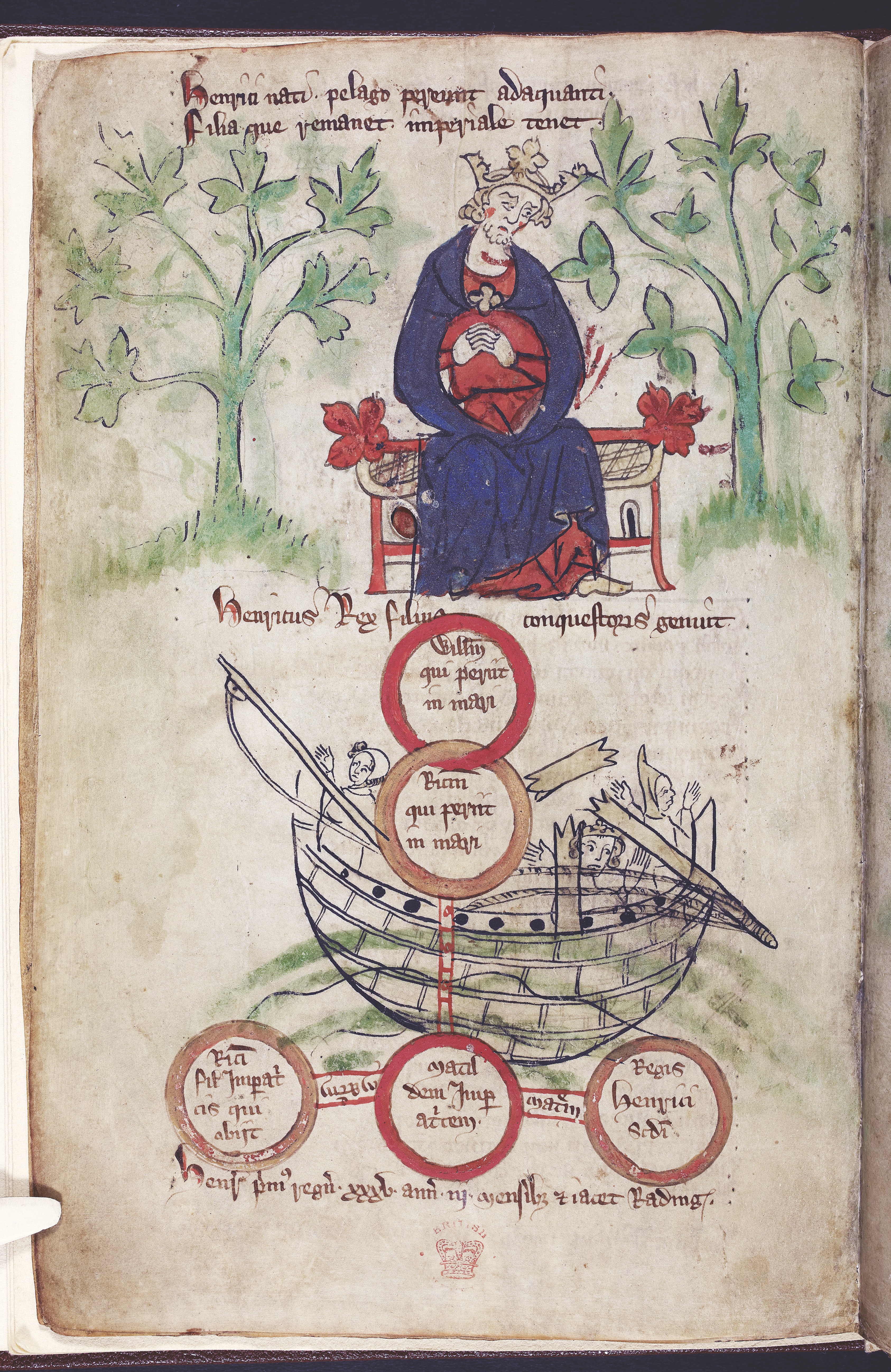

King David I of Scotland had invaded England that year in support of his niece, Matilda, then embroiled in a fight against her cousin, Stephen of Blois, for control of the English throne. This period of civil war, known as the Anarchy, raged in England from 1135 until 1153. Sparking it was a succession crisis following the drowning death of William Adelin—Henry I’s only legitimate son—in the tragic 1120 wreck of the royal transport White Ship. Although the king had designated daughter Matilda as his heir, on Henry’s death in 1135 his nephew Stephen had seized the throne.

Matilda and husband Geoffrey of Anjou moved to overthrow King Stephen by launching an invasion from their base in English-held Normandy. Set for 1139, the cross-channel assault was preempted when King David invaded from the north.

David’s forces soon conquered much of Northumbria. A force he sent into Lancashire routed an English army at the Battle of Clitheroe on June 10. Monastic English chroniclers described the invading Scots as “more atrocious than the pagans” and accused them of committing every kind of atrocity, from the credible selling of women and children into bondage to the hyperbolic drinking of the blood of slain children. In truth, many communities guaranteed their safety by promising not to move against David. Some northern English lords (such as Eustace Fitz John) joined forces with David and declared loyalty to Matilda. Regardless, contemporary sources record widespread alarm at the invasion. In part that was David’s intention. If he could divert Stephen’s attention north, that would make Matilda’s invasion from the south easier.

As rumor spread David intended to march on York, a patchwork force gathered to confront him. Leading it was the elderly Archbishop Thurstan of York, Stephen’s lieutenant in the north. Stephen himself was occupied with a rebellion of pro-Matilda barons in the south. Loyal commanders from as far south as Derbyshire soon arrived in York with their contingents. From there the English army first marched north to Thirsk, then set out on the Roman road to Northallerton (roughly tracing the present-day A19). The ailing Thurstan was unable to accompany them. In his stead marched Bishop Ralph Nowell of Orkney with a cadre of clergymen. Before them they held aloft the banner of St. Peter the Apostle from York Minster. Other contingents carried similar banners.

The idea of sending a standard ahead to encourage one’s army was likely inspired by biblical accounts of the Ark of the Covenant, containing the stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments, which the ancient Israelites bore into battle draped in a veil and suspended by long poles. Roman legions carried the aquila (“eagle”), a standard capped by a bronze representation of the raptor and ascribed quasi-religious significance.

At the time of Stephen and Matilda’s clash for the English throne, the French marched into battle raising the Oriflamme (from the Latin for “golden flame”), the sacred banner of the Abbey of St. Denis. However, doing so was not common practice in 12th century England.

The elaborate construction for which the forthcoming Battle of the Standard was named took shape at Northallerton. First, the men erected a frame to support a ship’s mast. Atop the mast was hung a pyx—a silver container containing Communion bread—and beneath it the standards of St. Peter, St. John of Beverley and St. Wilfrid of Ripon (other sources add the banner of St. Cuthbert of Durham). The presence of banners from the most important churches in north England—York Minster, Beverley Minster, Ripon Minster and, perhaps, Durham Cathedral—suggest just how dire a threat David’s invasion posed in the minds of the English. For additional reassurance the clergy may have read aloud to the men from Romans 8:31: “If God is for us, who can be against us?” Several early illustrations depict the standard perched atop a wheeled-cart for mobility. Thus it served not only as a sign of divine support, but also as a rallying point for the English.

Northallerton sits 10 miles south of the River Tees, which formed the border of Yorkshire. No sooner had the English arrayed themselves a couple of miles north of town than the Scots came into view, advancing south from the Tees.

The battlefield was hemmed in by marshy ground. Cinnamire marsh, on the low ground to the English left, protected their flank from being turned by the more numerous Scots, while on the English right Brompton Grange and The Grange were also dominated by marshy terrain. Thus the Scots would be inexorably funneled toward Northallerton, and by deploying on or near Red Hill, the English could block their southward advance and force battle. The English numbers may have been sufficient to deploy in an unbroken line the quarter mile or more between Cinnamire and Brompton Grange.

The English likely centered their lines on ground marked by present-day Scotpit Lane, perhaps as far south as present-day Red Hill. The Scots drew up farther north on what has since been known as Standard Hill. Some modern-day reconstructions depict the English battle line arrayed on Standard Hill with the Scots deployed south of them, closer to Northallerton. This is clearly wrong, for that would suggest the Scots managed to get behind the English, a nearly impossible task, given the terrain. Likewise, to assert the English were deployed on Standard Hill and the Scots farther north also makes no sense, given the relative location of Scotpit Lane, the spot where most of the Scottish casualties fell and were buried.

Contemporary chronicler Prior Richard of Hexham estimated Scottish numbers at 26,000 men. While no such estimates are available for the English forces, they were outnumbered, perhaps massively. Poorly armed peasants made up much of their ranks. The greater part of the English knights fought afoot, some interspersed with archers in the front line, while most others gathered about the standard. Foot soldiers led the horses to the rear and held their leads, to prevent them shying away amid the clamor of the oncoming Scots.

Most of the Scots were also afoot, their horses held at the rear. David and his knights formed up in the center, wrote Richard of Hexham, while “the rest of the barbarian host poured roaring around them.” Richard left scant details of the battle itself, relating only that it was fought between the “first and third hours” of August 22. He did note that “numberless” Scots were slain in the first attack, the rest throwing down their arms and fleeing. An account by fellow contemporary chronicler Abbot Ailred of Reivaulx is more detailed, though it contains problematically fictional elements, such as long speeches allegedly made by participants.

According to Ailred, David intended his knights and archers to advance first, but he was opposed by the men of Galloway, who maintained it was their right to be in the front rank during the attack, owing to their recent victory over the English knights at Clitheroe. David acceded to their demands. As many as 7,000 Galwegians took the front line. Behind them, line abreast, stood the three Scottish divisions. David’s son, Prince Henry, led the division on the Scottish right, comprising his knights and archers as well as the men of Cumbria and Teviotdale. David was in the center with Scots, Moravians and the knights of his English and French allies. The left comprised the men of Lothian, Lorne and the Scottish isles. Ailred claimed the English were so few that they formed but a single division (he uses the term column), the knights in front with archers and lancers distributed among them. This was an unusual formation but entirely possible.

The Galwegians gave their customary three fearsome battle cries before charging the English lines, initially driving back the lead ranks of English spearmen. The English knights quickly recovered, however, holding their own as their archers took a devastating toll on the unarmored Galwegians, said to be so stuck with arrows they resembled hedgehogs. In agony the men of Galloway flailed blindly at friend and foe, their charge dissipating.

David has been criticized for having allowed the Galwegians to lead the attack, instead of using better armored troops. But there were sound reasons for him to have taken the action he did. First, the Galwegian charge had proved decisive against similarly armored enemies at Clitheroe. Second, the marshy terrain to the left and right of the English position meant David could not outflank them, thus only a frontal attack was feasible. Perhaps David hoped the Galwegians would absorb English attention—and arrows—until he could send better troops into the fray.

At the moment when the Galwegians were most hard-pressed, Prince Henry led out the Scottish right, putting the English left to flight and charging down on the men holding the horses. The English retreated a quarter mile, the poorly armed peasants scattering before them. While several reconstructions of the battle depict Henry’s charge as mounted, there are reasons to believe the Scots advanced afoot.

As the fighting grew ever more desperate, one quick-thinking English soldier, known to history only as “a certain prudent man,” raised aloft the severed head of a fallen Scot and cried out that King David was slain. To quell the ensuing panic in his ranks, David threw aside his helmet to prove he remained very much alive, but the damage was already done. He could not sustain the fight and retreated. David’s retiring royal banner spread word to the surviving Scots of his capitulation. Prince Henry, fighting behind the English front line, saw the reversal and ordered his men to drop their banners and make for the Scottish lines, hopefully intermingling unnoticed with the English pursuers. They could only have done this effectively if dismounted, as his English opponents probably were. An alternative theory suggests Henry’s men may have charged in mounted but become unhorsed over the course of the combat.

Several modern accounts posit David and his division acted as a reserve and fled without ever having engaged the English. But had David not been in the thick of the fight, why would his men believe the ruse that he’d been killed? As the Galwegian charge faltered, that all-important “head fake” likely prompted them to break and flee. Two of their leaders, Ulgric and Donald, had already fallen. According to Ailred, the unengaged men of Lothian, Lorne and the islands on the Scottish left also fled in haste. It is unclear exactly in what order events took place. One reconstruction places Henry’s charge late in the battle, at the moment of the rout, to mask the king’s retreat.

According to the chroniclers, the English suffered few casualties, though given the initial success of both the Galwegian charge and Prince Henry’s attack, that seems unlikely. Sources trumpeting the victory likely underestimate English losses and likewise exaggerate Scottish casualties. That said, only one English knight of note—Ilbert de Lacy—is known to have fallen. Richard of Hexham wrote that more Scots died during the retreat than in battle. He paints a vivid picture of the aftermath:

The plain was strewn with corpses; very many were taken prisoner; the king and all the others took to flight; and at length, of that immense army, all were either slain, captured or scattered as sheep without a shepherd.

Richard notes that while no estimate could be made of the enemy dead, 10,000 men were missing when David’s army returned to Scotland. Other sources cite as many as 12,000 Scottish dead. Fifty Scottish knights were captured, all ransomed by November.

The English did not pursue the retreating Scots far, possibly because no knights were mounted, as their horses had been driven off a quarter mile by Prince Henry’s charge. It is, therefore, reasonable to suggest that Standard Hill was not named as the location of the initial English deployment, but rather as the farthest extent to which they advanced with the standard on its wheeled cart. From that vantage, roughly where the Scots had drawn up their battle lines, the standard oversaw their retreat and the victory its English followers believed it had wrought.

The defeated David regrouped at Carlisle, there fretting the fate of his son till Henry joined him two days later. His men made their way back to safety piecemeal. Amid the rout many of the less well-armed and -armored Scots fell to English arrows, swords and spears. Of the estimated 200 knights that accompanied Henry, only 19 made it back to Scotland with their armor, many without their horses. At Carlisle the king negotiated a truce with Stephen. Under its terms David would retain his territorial gains in Cumbria and Northumbria, which he did until his death in 1153. He advanced his border to the River Tees and installed son Henry as Earl of Northumbria.

Today several landmarks north of Northallerton bear names related to the Battle of the Standard, notably Standard Hill, Scotpit Lane and Red Hill. Their relation to one another is useful when plotting the course of the battle.

The term “hill” in this area is overly generous. Neither Standard Hill nor Red Hill are hills in any real sense, more gentle rises of a few feet from the surrounding plain. Local tradition has it Red Hill was so named because its slopes ran red with blood during the battle. The Scottish casualties were reportedly buried where the majority of them fell—at Scotpit Lane, marked on early maps as the Scots Pits. That makes sense, as it would have been difficult to move the bodies of the fallen to a different location.

Though history records the battle as a Scottish loss, David did achieve his alternative purpose of distracting Stephen in order to aid Matilda. Despite the truce, David kept a 14,000-man army on his southern border, forcing the English to keep a wary eye to the north. A year later Matilda invaded as planned. Despite early successes the war soon devolved into a stalemate, Matilda controlling Normandy and much of southwest England, Stephen the remaining territory north to the River Tees. Matilda returned to her husband in Normandy in 1148, leaving their son, Henry, to continue the fight in England. He ultimately succeeded and was crowned Henry II in 1154, eight weeks after Stephen’s death. It seems God wasn’t with the usurper after all. MH

Australia-based Murray Dahm is the author of Macedonian Phalangite vs. Persian Warrior. For further reading he recommends The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, Comprising the History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Accession of Henry II, by Henry Huntingdon; Battles Fought in Yorkshire: Treated Historically and Topographically, by Alex. D.H. Leadman; and Battles and Battlefields in England, by Charles Raymond Booth Barrett.

This article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: