As in most wars, servicemen during World War II anticipated one of two fates. Either they would fight until the end of the war or they would die. Few considered a third possibility that proved to be the fate for millions of them: becoming a prisoner of war.

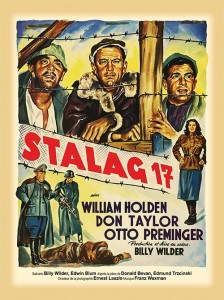

In many cases being a POW was effectively just a way station on the journey to death. An estimated 40 percent of POWs perished at the hands of the Japanese, who held their prisoners in contempt for having surrendered. The mortality rate for Soviet POWs of the Nazis was especially high, thanks to a policy of systematically working them to death: Nazis considered Russians, like Jews, to be Untermenschen—racially inferior. But for Western Allied POWs, whom Germany treated in at least loose compliance with the rules of the Geneva Convention, the third fate was a very real possibility. Hundreds of thousands of French and British soldiers, together with about 93,000 Americans, spent part of the war as unwilling guests of the Third Reich. The 1953 comedy-drama, Stalag 17, directed by the legendary Billy Wilder, focuses on a barracks containing about 20 American POWs.

Wilder adapted Stalag 17 from a hit Broadway play of the same name written by Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski. Both playwrights had been inmates in Stalag 17B, a camp for Allied airmen near Krems, Austria, that contained about 30,000 POWs. Bevan and Trzcinski were among the 4,200 Americans there, mostly noncommissioned officers—gunners, flight engineers, and radio operators—and this is true of the characters they created as well.

The plot of Stalag 17 is driven by suspicions that a German stool pigeon is among the barracks’ residents. But the film’s real subject is the efforts of the POWs to deal with the monotony, petty squabbles, and hardships that attended captivity. Both the play and movie begin with a voice-over by Clarence Harvey “Cookie” Cook (played by Gil Stratton in the film), complaining that every World War II movie featured deeds of derring-do, with not one about the day-to-day tedium of life in a dreary POW camp. Had he been able to peer into the future, Cookie would have been equally exasperated by the more than 50 POW movies that would follow Stalag 17—most of which still feature deeds of derring-do, particularly mass escapes.

At the center of the film is a scrounger named Sefton (played by William Holden, in an Oscar-winning performance). Loosely based upon an actual airman in Trzcinski’s barracks, Sefton specializes in easing the monotony. He organizes mouse races, concocts “white lightning” from a makeshift distillery, and allows his fellow inmates to gaze through an improvised telescope at female Soviet POWs bathing in an adjacent compound. All these services come at a price: Sefton collects a fortune in chocolate and cigarettes—the coin of the realm in POW camps—and uses these to bribe the German guards in order to acquire luxuries such as whiskey, cigars, and fresh eggs. By POW standards, he is a rich man.

He is also cynical, aloof from his fellow prisoners, and willing to take bets on anything, including the outcome of an attempted escape. It’s the failure of this escape that convinces the barracks’ residents a traitor is among them. Suspicion falls heavily on Sefton. He supplies his captors with chocolate and cigarettes, so why not with information?

While Sefton is at the center of Stalag 17’s drama, other characters supply most of the comedy, none more so than “Animal” (Robert Strauss, in an Oscar-nominated supporting performance) and his sidekick Harry Shapiro (Harvey Lembeck). One of the film’s highlights is a slapstick scene in which Animal and Harry make a put-upon show of painting a broad white line along the ground from the American section to the adjoining compound, where in a large hut—dubbed “the Brick Kremlin”—female Soviet POWs remove their clothes for delousing. The act is so absurd and so typical of the pointless labor assigned to POWs that the guards at the gate let them through without question.

“Marko the Mailman” (William Pierson) is hilarious as the runner who carries the news from one barracks to another, reading in a nasal voice and prefacing each item with the phrase, “At ease!” Otto Preminger, a director famous for his imperious style on the set of his films, plays camp commandant Colonel von Scherbach, sending up his own image in a caricature of a Nazi martinet. Sig Ruman supplies yet more humor as Sergeant Johann Sebastian Schulz, the buffoonish guard who oversees the barracks. (The TV series Hogan’s Heroes simply hijacked these two to create Colonel Klink and Sergeant Schultz.)

All of this action occurs against a realistic backdrop of deep mud and winter chill, drafty buildings, straw-filled mattresses, cold water, ham hock soup bereft of ham hocks, and grime everywhere. The success of Stalag 17 largely turns on Billy Wilder’s genius in balancing drama, comedy, and realism. Ultimately it is realism that wins out. The film’s climax resolves the mystery of the informant—needless to say, it isn’t Sefton—but as the credits roll, nearly all of its characters remain confined to their gray purgatory, consigned to endure the third fate until final victory is won. ✯

This excerpt was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.