A popular image of German militarism is the helmet, whether the spiked Pickelhaube (“point bonnet”) of Kaiser Wilhelm II or its successor the Stahlhelm (“steel helmet”). Behind the latter’s infamous shape, however, were practical considerations.

In 1915, as World War I settled into the static meat grinder of trench warfare, Prussian engineering professor Friedrich Schwerd of the Technical Institute of Hanover studied the nature and circumstances of returning soldiers’ head wounds and recommended the use of a steel helmet, which would better protect wearers from projectiles or shrapnel than the boiled leather Pickelhaube still largely in use. Schwerd based his prototype on the broad-tailed medieval sallet.

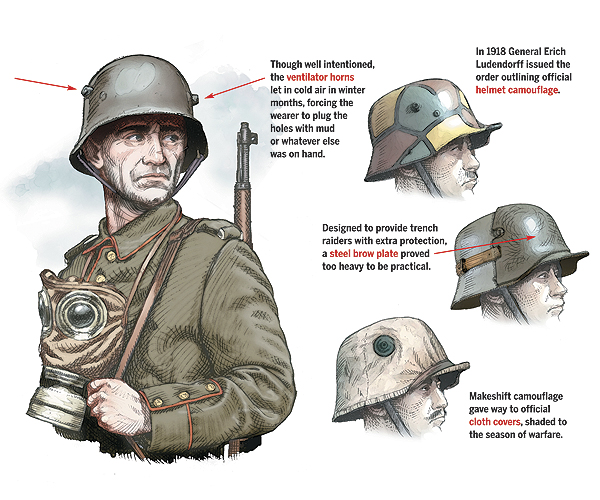

German metalworkers crafted the Stahlhelm from martensitic silicon/nickel steel, a harder alloy than that used in the British Brodie helmet. Fabrication of each Stahlhelm required the use of heated dies, making for a greater unit cost than the one-piece Brodie. The liner comprised a leather headband, three padded leather pouches, adjustable leather or fabric cords, and a one-piece leather chinstrap. Ventilator horns ensured airflow.

On the strength of successful field tests, the German army placed an order for 30,000 helmets, though it didn’t officially issue the Stahlhelm until New Year’s Day 1916, hence its designation as the Model 1916. It saw its first combat use during the February 1916 Verdun offensive. A succession of refinements followed, and variations on the “coal scuttle” became standard headgear in dozens of armies worldwide, most notably in Germany’s own World War II Wehrmacht. Its basic design is echoed in the Kevlar helmet used by American service personnel today.