When the Germans overran France in June 1940, the only major power that still stood against them was Britain—and even though it was separated from the European continent by the English Channel, its prospects of standing for any considerable length of time seemed slim to most observers. Germany’s navy was no match for Britain’s, but its air force, or Luftwaffe, had been the primary instrument of victory over Poland, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and France. Adolf Hitler’s Luftwaffe commander in chief, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, assured him that air power would suffice to bring the British to their knees as well.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill was making no idle boast when he said that Hitler knew the importance of achieving a swift victory over England, for the British Isles were a conduit through which a vast reserve of manpower could be staged against the Germans and their Italian allies. Britain’s colonial empire was on the wane, but it had largely been replaced by an economic commonwealth of independent and semi-independent nations that would aid the mother country.

Among the most distant but loyal of those faraway countries was New Zealand. Many “Kiwis” were already serving in the Royal Air Force (RAF) when World War II began. Two of them, Colin Gray and Alan Deere, would be among the best-known heroes of the Battle of Britain—and Gray would go on to become New Zealand’s highest-scoring ace.

Colin Falkland Gray was one of twin boys born in Christchurch, New Zealand, on November 9, 1914. After completing his education at Christ’s College, he worked for a while as a junior clerk, but he soon decided on a more exciting vocation—aviation. He and his brother, Kenneth, applied for short service commissions in the RAF in April 1937. Kenneth was accepted, but Colin, who had had a history of osteomylitis, was rejected on medical grounds. Undaunted by the setback, he spent time as a farm laborer to develop his muscles and stamina, then reapplied for RAF service—and was turned down again. After a third attempt, determination overcame physical limitations, and Gray was accepted in September 1938.

New Zealand had its own RAF facilities, but Ken Gray had opted for service in England, and Colin chose to do the same. He left in December and began his flight training at Hatfield, under a contracted civilian pilot, in January 1939. After graduating in April, Gray was commissioned an acting pilot officer and posted to No. 11 Fighter Training School at RAF Shawbury, Shropshire. Flying Hawker Harts, he completed the course in July. Since the other trainer at the school was the twin-engine Airspeed Oxford, Gray knew at that point that he was destined for single-engine fighters.

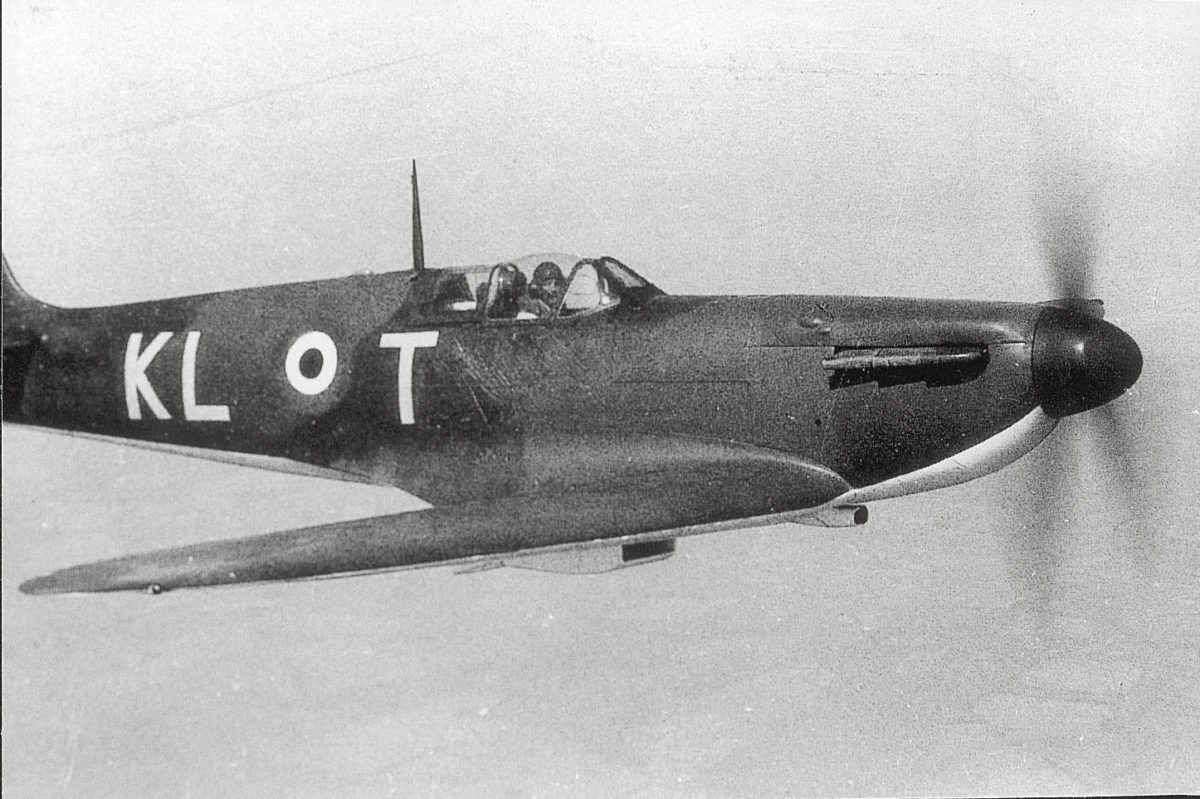

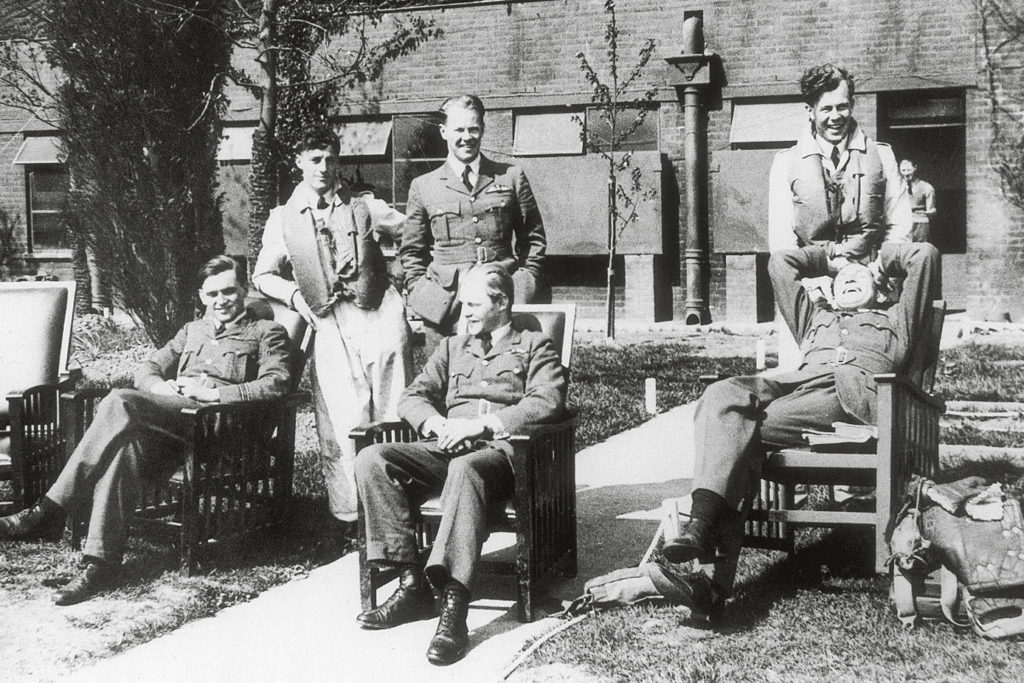

Colin Gray had yet to be posted to an operational unit when Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. In October, he was sent to 11 Group Fighter Pool at St. Athan, from which he was assigned to No. 54 Squadron on November 20. Based at Hornchurch, No. 54 Squadron was then equipped with the latest fighter in the RAF—the Supermarine Spitfire Mark I. Among the squadron mates with whom Gray would see intense action in the year to come were Flight Lt. James Anthony Leathart, a student of electrical engineering from Liverpool University, consequently known as “Prof”; Pilot Officer John Lawrence Allen; Flying Officer Basil Hugh “Wonky” Way; and Sergeant John K. “Jock” Norwell, all of whom were also Britishers; and fellow Kiwi, Alan Christopher Deere.

Meanwhile, Pilot Officer Kenneth N. Gray had become a pilot in Armstrong Whitworth Whitley Mark V bombers in No. 102 Squadron, based at Linton-on-Ouse, Yorkshire, flying his first wartime mission on September 9, 1939. During a reconnaissance over the Cuxhaven and Heligoland areas on the night of November 27, lightning struck Ken Gray’s plane, tearing a large area of fabric from both wings, jamming a flap in the down position and shorting out the radio. In spite of the damage, Gray and his co-pilot, Pilot Officer Frank H. Long, also a Kiwi, managed to fly 340 miles to a safe landing at Bircham Newton, Norfolk. Both Gray and “Tiny” Long subsequently became the first New Zealanders to be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). Ken Gray also became the only New Zealander to receive the Czech War Cross, following a leaflet-dropping raid on Prague in severe weather on March 9, 1940.

Ken Gray continued to fly bombing missions over Germany and—after the Germans invaded Norway on April 9—over targets in the southern part of that country. Then, on the morning of May 1, while ferrying a Whitley from Kinloss, Scotland, to Driffield, his plane crashed on the northern slopes of Hill of Foundland, near Aberdeen, Scotland. Ken and four others aboard the plane were killed, and of the three survivors, two later died of their injuries. “I was completely stunned by the news,” Colin wrote in his memoirs. “It seemed such a cruel twist of fate that a skillful and experienced pilot, who had successfully completed many long and arduous missions over enemy territory, should lose his life in such circumstances….At the time of his death Ken had been with his squadron for nineteen months and had been flying on active operations for eight months—he must have been nearly due for a rest.”

Number 54 Squadron alternated between Hornchurch and Rochford throughout the winter of 1939-40, maintaining a constant alert for German air raids or flying convoy patrols over the North Sea. But the unit did not see action until May 1940, when the defeated British and French forces began their evacuation from Dunkirk. On May 21, Johnny Allen claimed first blood for 54 in the form of a Junkers Ju-88 off Dunkirk, shortly followed by a claim on a Heinkel He-111 by Prof Leathart, but neither kill was confirmed.

Two days later the unit got a special assignment. Squadron Leader Francis L. White, the commander of No. 74 Squadron, had shot down a Henschel Hs-126 that was reconnoitering Dunkirk, but not before the German rear gunner had shot holes in his radiator, the resulting glycol leak compelling him to land at Calais-Marck, France. The RAF had left France on May 22, and with German forces rapidly closing in around Dunkirk, No. 54 Squadron, which had a two-seat Miles Master trainer for use as a squadron hack, was asked to evacuate White. Leathart was to briefly land the Master at Calais-Marck airfield, take White aboard and immediately take off for England. Al Deere was selected to provide low-level escort for Leathart, while Johnny Allen would cover them both from a higher altitude.

When the trio reached Calais-Marck, Leathart landed, but he failed to see White approaching and took off without him. Deere was gesturing for him to go down and try again when he heard Allen saying over the radio, “Twelve Me-109s approaching at 6,000 feet.” The two Spitfires then plunged into the oncoming formation of Messerschmitt Me-109Es, and a wild dogfight ensured. Deere hit one Messerschmitt and saw it make a forced landing in the water near the beach, its tail sticking up in the air. He then spotted one on Allen’s tail, got in behind it and shot it down in flames. Deere was firing at a third enemy fighter and thought he had damaged it when his ammunition ran out. By then, Leathart had landed again, White had scrambled into the cockpit and the two were safely on their way back across the Channel for England.

Rejoining Allen, Deere asked, “How did you get on, Johnny?”

“One destroyed and two probables,” Allen replied. “Wasn’t it great fun?”

Leathart was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his part in the rescue of White, while Deere and Allen each received the DFC for protecting them. The fight also gave the Luftwaffe’s Me-109E pilots one of their first tastes of combat with the Spitfire—and an early indication of the tough fight they could expect whenever they met it in the future.

Colin Gray got the chance to show his mettle on May 24, when his six-plane patrol encountered a Staffel (squadron) of Me-109Es over Calais. Allen, Norwell and Flight Lt. Dorian George Gribble each downed an Me-109 over Calais. Deere shot one down northeast of St. Omer, and Gray was credited with two probables. Gray scored his first confirmed victory the following day, after escorting Royal Navy Fairey Swordfish biplanes on a mission to bomb German forces at Gravelines. A pilot’s first victory is usually memorable, but Gray had an extra reason to remember May 25, 1940, because it was also the first time he had a close brush with death.

“We were continuing patrolling when the familiar cry of ‘Tally Ho!’ came over the RT [radio-telephone],” he said in a 1993 interview. “We sighted a formation of Me-110 twin-engine fighters and climbed to attack, but in doing so were bounced by about a dozen Me-109s. I managed to get behind one and gave him a good burst, which slowed him down—the pilot went overboard [bailed out]. Suddenly my aircraft shook, and a hail of bullets and two cannon shells hit. One of the cannon shells hit the access hatch behind the cockpit and demolished the air-pressure system, leaving me without flaps, brakes and guns.

“The second cannon shell hit the port aileron, jamming it in full up position and causing the aircraft to flick over in a spiral dive. It was this forced maneuver that probably saved me, quicker than I could have reacted.

“I managed to free the joystick which was hard over to the left and regained aileron control. The cannon shell had also severed the air speed indicator line so I had no idea of my speed.

“Using emergency boost, I immediately headed for home. By using the emergency ‘blow-down’ [compressed air] I was able to lower the undercarriage for landing back at Hornchurch, which on the first attempt, fast and without flaps or brakes, was very hairy. However, on the second attempt I made it OK.”

Gray was fortunate enough to live and learn from his mistake—concentrating too long on the enemy plane in his sights while forgetting to check his own tail. Luckily for him, Norwell and another pilot attacked the Me-109 that had shot him up, sending it down south of Gravelines. The Me-110 Zerstörer (“destroyer”) long-range escort fighters, which Göring had touted as the key to German aerial supremacy, fared poorly against the Spitfires that day, two falling victim to Allen, one to Deere and another probably downed by Leathart.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

After the French had capitulated on June 22, the Germans and British spent nearly a month preparing for the struggle to come. Most aerial action during that time took the form of anti-shipping attacks in the Channel, or interceptions of intruding reconnaissance planes. Gray, Norwell and a third pilot probably downed a Dornier Do-17 five miles southwest of Deal on July 3, and on July 13 Gray shot down an Me-109E of Jagdgeschwader 51 between Dover and Deal. Then, in mid-July, the Luftwaffe began crossing the Channel in force to attack RAF airfields and try to seize control of the sky over England itself. The Battle of Britain had begun.

Britain’s aerial defenses were organized to cover different sections of the island, with Air Marshal Keith Park’s 11 Group, including No. 54 Squadron, operating over the southeastern sector—and therefore bearing the brunt of the Luftwaffe’s attention. On July 24, No. 54 Squadron took off from Rochford to engage German fighters, while six Spitfires from No. 64 Squadron attacked two Staffeln of Do-17 bombers. The escort that No. 54 Squadron’s Spits ran into was comprised of 40 Me-109Es of III Gruppe, Jagdgeschwader 26 (III/JG.26), flying their first mission under their newly promoted commander, Major Adolf Galland. A long, vicious dogfight ensued, during which No. 54 Squadron claimed six Messerschmitts, including one by Gray, one by Deere and one by George Gribble, as well as eight probables, one of which was also claimed by Gray. In actuality, the British had been fooled by the evasive split-S dives and smoking engines of the Me-109Es into overestimating the damage they had done. Only one of Galland’s pilots, 2nd Lt. Josef Schauff of JG.26’s 8th Staffel (8/JG.26) was killed in the fight, while III Gruppe’s technical officer, 1st Lt. Werner Bartels, was shot up by one of No. 64 Squadron’s Spitfires over Margate, forced to belly-land near the coast, seriously wounded and taken prisoner. One of No. 54 Squadron’s pilots made a forced landing with minor injuries, another Spitfire was heavily damaged, and Johnny Allen, victor over seven enemy planes, crashed and was killed while trying to land his riddled fighter.

Recommended for you

Galland, who had claimed both of III/JG.26’s victories that day, was not pleased with his group’s performance, and he made no secret of it to his pilots that evening. That first encounter, he later said, removed any doubts from his mind about how formidable an opponent the RAF would be. Nevertheless, JG.26 encountered Nos. 54 and 64 squadrons again on the 25th and shot down three Spitfires, Wonky Way being among the losses.

Air Marshal Park, who made a policy of rotating his squadrons to more northern airfields to rest his pilots whenever possible, sent No. 54 Squadron to Scotland for 10 days in early August. No sooner had the squadron returned than it was in action again, as the Luftwaffe began a supreme effort to eliminate the RAF both in the air and at its air bases. On August 12, 18 Do-17s of Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Wing) 2 (KG.2) devastated Manston airfield. Although intercepted by Hawker Hurricanes of No. 56 Squadron, the German gunners shot down two of their attackers, and all the Dorniers returned to their base at Arras, France.

At about the same time the Hurricanes attacked, No. 54 Squadron’s Spitfires arrived, but they were attacked in turn by Me-109Es of I Gruppe, JG.26, led by Captain Kurt Fischer. In the ensuing dogfight, Gray officially became an ace when he shot down two Me-109Es between Dover and Cap Gris Nez; his fellow Kiwi, Al Deere, downed an Me-109E and subsequently destroyed an Me-110. Two of No. 54 Squadron’s pilots were wounded but succeeded in crash-landing their Spitfires, while No. 64 Squadron, arriving late on the scene, lost one Spitfire, whose wounded pilot bailed out, and a second that made a forced landing. I/JG.26, which claimed four Spitfires, lost two Me-109s. One pilot, 1st Lt. Friedrich Butterweck of 1/JG.26, was killed. The other, 2nd Lt. Hans-Werner Regenauer of 2/JG.26, was firing at a Spitfire that was on the tail of his flight leader when his plane was hit in the cooling system. “I hid in a cloud and headed toward the French coast,” he later reported, but his plane started to lose altitude and then the engine stopped. “I bailed out at about 200 meters, and after a bath lasting about seven hours, was taken aboard an English ship.”

Fierce air battles now became almost a daily occurrence, and the RAF fighter pilots were often compelled to fly several missions a day, testing their endurance to the limit. Gray probably downed a Do-17 on August 15, the same day he was awarded the DFC. His squadron was less successful in preventing 26 Junkers Ju-87Bs of II Gruppe, Stukageschwader 1 from attacking Lympne at 12:30 that afternoon, losing two Spitfires to Galland and another pilot of III/JG.26 (which erroneously claimed seven Spitfires). “It was an impressive yet frustrating sight as the dive bombers, in perfect echelon formation, swept toward the airfield and peeled off to attack,” Deere wrote in his autobiography, Nine Lives. “A mere handful of Spitfires altered the picture very little as, virtually lost in the maze of 109s, they strove to interfere.” During a later patrol at 4 p.m., Deere chased an Me-109 all the way to France, then was beset by two other Me-109s—probably flown by Galland and 1st Lt. Joachim Müncheberg of III/JG.26, returning from their last mission of the day. Deere was chased back over the Channel and shot down in flames. He half-rolled, bailed out and came down unhurt near Ashford.

August 15 had seen the peak of Luftwaffe activity over England—a record 2,000 sorties—along with its severest losses. The RAF had claimed 182 German planes shot down, while the Germans had actually lost 76, including 40 fighters. The Luftwaffe, in turn, claimed 101 victories, while the British actually lost 35 fighters that day.

Gray added two Me-109Es to his score east of Hornchurch on August 16, also damaging a Do-17 and an Me-110. Poor weather curtailed air activity on the 17th, but Göring ordered General Albert Kesselring, commander of Luftflotte (Air Fleet) 2, to prepare his units for a supreme effort to destroy 11 Group’s airfields on the following day. Among the targets was Hornchurch, assigned to KG.2’s Do-17s, escorted by 25 Me-109Es of JG.51.

On August 18, Gray, Norwell and two squadron mates teamed up to down an Me-110 possibly flown by 2nd Lt. Hans-Joachim Kästner of Zerstörergeschwader 26 (ZG.26), who crash-landed near Newchurch in Kent. Flight Lt. William P. Hopkin and another pilot shot down another ZG.26 Me-110 over Manston. Hornchurch was attacked that afternoon, and nine RAF squadrons were vectored in to its defense. Several bombers were shot down, and Gray damaged one Do-17. Hopkin downed a Do-17 and damaged an Me-110 in the Clacton area, while Gray destroyed another Me-110 over Clacton and damaged two more over Dover and Folkestone. Norwell damaged two Me-110s and Leathart probably damaged an Me-109 in the same fight. Gribble downed an Me-109 over Kent and damaged two He-111s and an Me-110. The Luftwaffe lost a total of 67 planes on August 18, including 15 of ZG.26’s Me-110s.

On August 22, No. 54 Squadron got six replacement pilots, including two from New Zealand, Pilot Officers M. Shand and C. Stewart. Both were eager to get into the fray, but they soon learned just how unforgiving an environment the Battle of Britain was for neophytes. Stewart was shot down during their first operational flight over Dover on August 24, bailing out and ending up in a hospital in Canterbury. Gray shot down one Me-110 and damaged two others in that same action, while Gribble damaged an Me-110 and destroyed an Me-109. On the following day, Gray splashed an Me-109E in the Channel, but Shand was shot down by other Messerschmitts, force-landed near Marston and ended up in a hospital bed adjacent to Stewart’s at Canterbury.

Gray damaged a Do-17 and two Me-109Es on August 26. Two days later, all of No. 54 Squadron’s fighters were sent up when 30 Dorniers came over to bomb the airfields at Eastchurch and Rochford. Leathart downed a Do-17, Gray damaged another and sent two of their Me-109 escorts limping home over the Channel in an equally damaged state. Gribble downed an Me-109 over Manston and a second over Dover. Deere probably got another Me-109 north of Foreland but then was shot down. It was the third time he had had to bail out since the Battle of Britain began, and he would take to his parachute four more times before it was over. Squadron Leader Donald O. Finlay, commander of No. 54 Squadron, was also shot down by an Me-109 on the 28th, bailing out and parachuting to earth wounded.

Just after lunch on August 31, Gray was taxiing to take off on his third scramble of the day from Hornchurch when he got an urgent radio call from the ground controller for No. 54 Squadron to take off immediately. “Realizing that something was seriously amiss, I opened the throttle and got the hell out of there,” Gray recalled. “When I looked back to see if my section was following, the airfield had disappeared in a cloud of smoke and rubble.”

German bombers had arrived over Hornchurch just as Gray learned of their approach. Deere was just taking off when a bomb hit tore a wing and the propeller from his Spitfire, which Gray said “hit the airfield inverted, then slid several hundreds of yards with Al trapped in what remained of the cockpit.”

A moment later, Eric Edsall’s Spitfire nosed into a fresh bomb crater. Ignoring the bombs still falling around him, Edsall emerged from the cockpit, ran across the airfield to Deere’s plane and extricated him through the door at the side of the cockpit. Deere suffered only a torn scalp, and both his wingmen likewise survived the destruction of their aircraft in the attack. Another squadron member, Sergeant J. Davis, also survived the destruction of his Spitfire by the exploding bombs.

Meanwhile, Norwell and Gribble got a measure of revenge by sharing in the destruction of one of the bombers’ Me-109 escorts over Hornchurch, while Gribble downed two other Me-109s over Manston and Dover, and Gray shot down another Messerschmitt over Maidstone. Gray’s adversary, 1st Lt. Willy Fronhöfer of 9/JG.26, crash-landed at Ulcombe and was taken prisoner. First Lieutenant Müncheberg of 7/JG.26 claimed a Spitfire in the fight, but he reported the loss of two of his pilots, Tech. Sgt. Martin Klar and Corporal Horst Lieback, who were taken prisoner.

There was to be no rest on September 1, when Gray destroyed an He-111 and an Me-109 east of Biggin Hill. An Me-109 and an Me-110 fell to Gray’s guns on September 2, and Leathart got another Me-109. Gray shared in the probable destruction of an Me-110 on September 3, as well as splashing an Me-109 off the French coast, while Leathart was credited with probably downing a second Me-109. Later that same day, the exhausted pilots of No. 54 Squadron were withdrawn north to RAF Catterick for a much-needed rest, and Prof Leathart was reassigned to the Deputy Directorate of Air Tactics.

By that time, Gray had flown 60 operational sorties in three weeks and had been credited with 16 enemy planes, as well as a shared victory.

Gray was promoted to the rank of flying officer in October, and on December 15 he was posted to No. 43 Squadron as a flight commander, although he was only with the unit a month before returning to No. 54 Squadron in the same capacity. In June 1941, he was transferred to No. 1 Squadron, flying night intruder missions in Hurricane Mk.IIBs, but his only success was to share with another pilot in the destruction of a Heinkel He-59 twin-engine floatplane 10 miles off Folkestone on June 16. On August 22, he flew a daytime patrol with No. 41 Squadron as a “guest” pilot in a borrowed Spitfire Mk.VB. The flight got into a dogfight with Me-109Fs off Le Havre, and Gray shot down one of them.

A week after that incident, Gray, who was awarded a bar to his DFC in September, was posted to command No. 403 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). He was transferred to No. 616 Squadron, RAF, two days later. In February 1942, he was assigned to headquarters (HQ) of 9 Group as squadron leader, tactics, serving in that role until September, when he returned to action with No. 485 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), to regain operational experience. He was then put in command of No. 64 Squadron, where he was able to familiarize himself with some of the first Spitfire Mk.IXs.

In December, Gray was sent to Algiers, Algeria, to serve as the tactics officer of 333 Group. When Wing Cmdr. Ronald Berry was promoted to command of 322 Wing on January 22, 1943, Gray was given command of Berry’s old unit, No. 81 Squadron. Based at Constantine, Algeria, the squadron had just become the first in North Africa to receive the new Spitfire Mk.IXs, which gave its pilots a distinct edge over the latest model Me-109Gs and Italian Macchi MC.202s.

Resuming his fighting career in earnest over Tunisia, Gray probably got an Me-109 over Bizerta on February 22, and he shared another probable victory over an Me-109 with “Ras” Berry over Mateur on March 2. Gray’s next confirmed victory was an MC.202 of the 368th Squadron, 151st Group, 53rd Wing, over Bizerta on March 23, resulting in the death of Sergeant Ugo Dal Pozzo. An Me-109G-6 fell to his guns east of Beja on March 25, Corporal Erich Föbus of 2/JG.53 being killed when his plane exploded on impact. Gray downed another Me-109G over Tunis on April 3, which may have been Sergeant Arno Fischer of 1/JG.53, who crash-landed near Teboura after suffering radiator damage. Gray most likely downed an Me-109 between Tunis and Bizerta on April 18. Two days later he shared in the probable destruction of an Me-109G in the same area—most likely 2nd Lt. Rolf Schlegel of 4/JG.53, who was wounded but managed a forced landing—and then shot down another over Tunis, which could have been either Staff Sgt. Otto Schmitt of 5/JG.53 or Corporal Hans Krüger of 6/JG.53, both of whom were killed. Gray damaged an Me-109 on April 23 and destroyed another over Beja on the 28th.

Following the surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia on May 13, Gray was awarded the DSO. He also succeeded Berry in command of 322 Wing, which moved to Malta to take part in the invasion of Sicily. Gray was flying his Spitfire Mk.IX, marked with his initials, “CG,” on June 14 when he downed an Me-109G over Comiso, Sicily, his victim probably being Corporal Reinhold Zimmermann of 6/JG.53, who was wounded but managed to land his damaged plane. Gray destroyed an MC.202 between Comiso and Biscari on June 17, and during the invasion of Sicily on July 10, he sent an Me-109G-6—possibly from 8/JG.53—crashing on the British beachhead.

Flying a Spitfire Mk.VC on July 25, Gray led his wing in an attack on an aerial convoy of Junkers Ju-52/3ms bringing fresh troops to Sicily from the Italian mainland. The transports were escorted by Me-109Gs of JG.27 and JG.77, but the German fighters were overwhelmed. In total, the “Jusi Massacre” resulted in the destruction of 26 Axis planes, No. 152 Squadron claiming 10 Ju-52s and two Me-109s, No. 242 Squadron claiming seven Ju-52s and one Me-109, and No. 81 Squadron accounting for four Ju-52s, an Me-109 and an Italian MC.202. The fighter credited to No. 81 Squadron’s new commander, Sqd. Ldr. William M. “Babe” Whitamore, DFC, was probably flown by 1st Lt. Heinz-Edgar Berres, commander of I/JG.77 and a 53-victory Experte, who was killed over Cap Milazzo. Gray himself accounted for two of the Ju-52/3ms, which brought his total up to 27 and two shared destroyed, making him the leading New Zealand ace of the war. In addition, he had at least 11 probables and 12 damaged. A second bar to his DFC was gazetted in November 1943.

While Gray was fighting over Sicily, his old Kiwi squadron mate, Alan Deere, was still operating over the Channel front, rising to command of the Biggin Hill Wing in spring 1943. By the time illness forced him to relinquish his command in mid-September 1943, Deere had been credited with 17 German aircraft destroyed plus one shared victory, three unconfirmed, four probables and eight damaged. Deere continued to serve in the RAF until 1967, retiring with the rank of air commodore.

Coincidental with Deere’s departure from Biggin Hill, Gray completed his second combat tour in September 1943. He served for a month with HQ, Middle East, in Cairo, Egypt, then returned to Britain to command 61 Operational Conversion Unit at Rednal on December 4. Gray was attached to a unit at Tangmere for a week’s operational flying in mid-January 1944, and then, on June 8, took command of the Spitfire wing at the Fighter Leaders’ School at Milfield. He was also attached to 145 Airfield for operational experience in July.

Gray returned to an operational role as wing leader flying at RAF Detling (Nos. 118, 124 and 504 squadrons, equipped with Spitfire Mk.IXs) on July 27, followed by the same duty at Lympne in August. Lympne’s Nos. 41, 130, 350 and 610 squadrons were equipped with the Spitfire Mk.XIVs, powered by the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine. Gray led both wings in defense of Britain against V-1 flying bombs, in operations over France and Germany, and over Arnhem during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden in September 1944.

After attending a senior commander’s course at Cranwell in January 1945, Gray’s next command was the air base at Skeabrae in the Orkney Islands, in February. He was granted a permanent commission in April, and in July he went home to New Zealand on leave and on loan to the RNZAF. While en route home, he learned of Japan’s surrender on August 14, 1945. One of his first peacetime acts was to marry Betty Cook at Gisborne on October 20. They would have two sons and two daughters.

Gray returned to Britain in March 1946 and was posted to the Air Ministry’s Directorate of Accident Prevention. On December 2, Sqd. Ldr. Gray was sent to the RAF Staff College at Bracknell, followed by a posting to the Air Ministry Directorate of Foreign Liaison in June 1947. He became a wing commander again in July 1947, and in January 1950 he joined the British Joint Services Mission in Washington, D.C.

September 1952 saw Gray posted as wing commander for administration at Stradishall, which had a unit devoted to converting RAF pilots to flying the jet-powered Gloster Meteor. In March 1954, he took command of Church Fenton as group captain, commanding Meteor squadrons Nos. 19, 72 and 609. In March 1956, he was sent to HQ, Far East Air Force, at Singapore, to serve as group captain of Operations during Operation Firedog against Chinese Communist guerrillas in Malaya. Gray returned to an Air Ministry job in February 1959, serving in the department of the assistant chief of air staff, Air Defense, as deputy director of Fighter Operations. He finally retired from the RAF on April 13, 1961, returning to New Zealand and working for the Unilever firm until 1979, when he retired as personnel director.

In 1984, Gray and his wife Betty moved to Waikanae, New Zealand, and in 1990, he published his autobiography, Spitfire Patrol. When Colin Gray died on August 2, 1995—followed in late September by the death of his old squadron mate and fellow ace Alan Deere—both New Zealand and Britain mourned the loss of not one but two of their greatest heroes of World War II.

Jon Guttman is Aviation History’s research director. For additional reading try: Colin F. Gray’s autobiography, Spitfire Patrol; and Nine Lives, by his squadron mate Alan C. Deere.