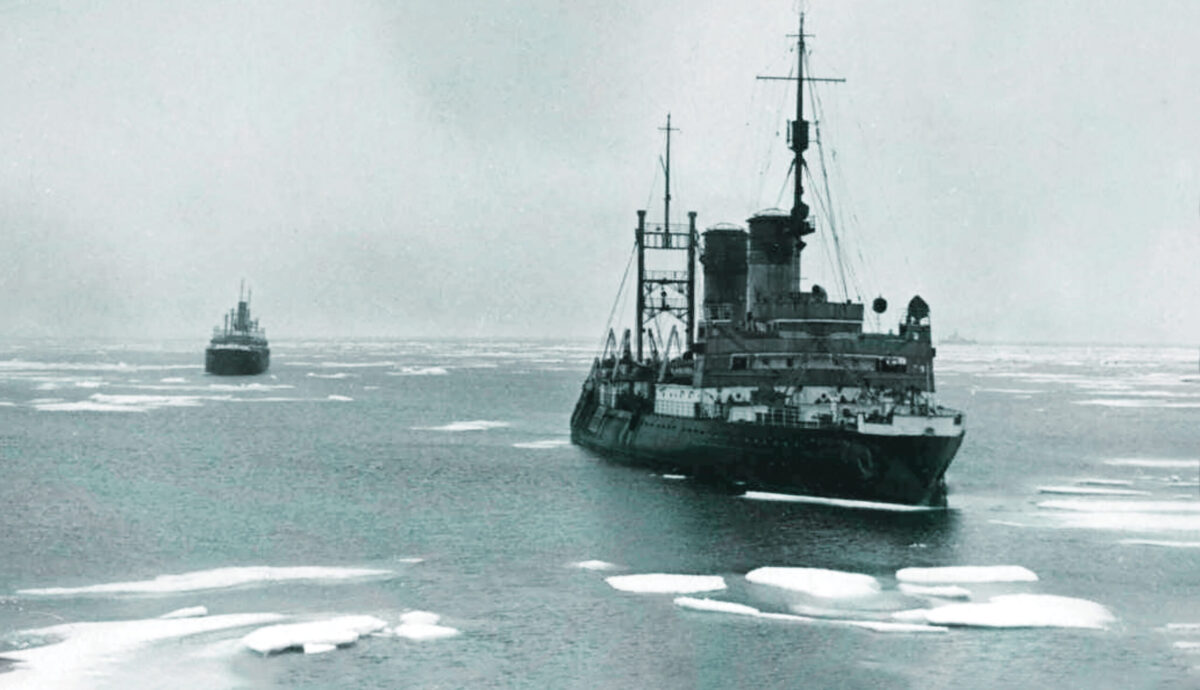

The German vessel Komet lay dead in the water, immobilized by Arctic ice. Captain Robert Eyssen watched from the wheelhouse as a large Soviet icebreaker crunched through the icepack toward him. The steel-reinforced bow of the 11,000-ton icebreaker Stalin could crush the Komet’s hull like an eggshell.

It was August 1940. The Nazi blitzkrieg was storming through western Europe, where the German Wehrmacht seemed unstoppable. But the war at sea was a different matter. Although German U-boats ravaged the Atlantic, the British Navy kept Germany’s few major surface warships mostly bottled up in their ports. Komet aimed to thwart the Royal Navy’s blockade and strike at vital sea lanes that sustained Britain’s war effort.

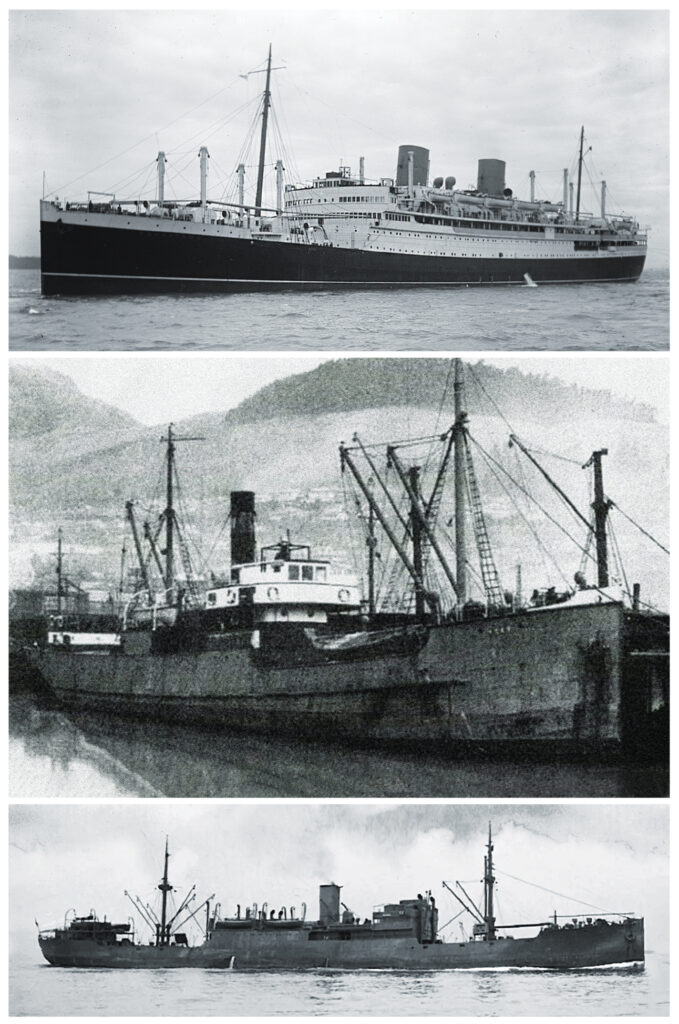

The shipwas no defenseless merchantman. In 1939, the German Navy commandeered the 7,500-ton passenger-cargo ship Ems and transformed it into an auxiliary cruiser, renamed KMS(Kriegsmarine Schiff) Komet. It was to be a commerce raider, designed to attack enemy vessels while disguised as a merchant ship sailing under a neutral false flag. Hinged steel deck plates concealed the ship’s main armament, six 5.9-inch guns. Captain Eyssen, however, did not lower the concealing deck plates and train Komet’s guns on the approaching icebreaker…because it was secretly an accomplice. Stalin was coming to free his vessel and clear a path through the ice so the German warship could transit the Russian Northern Passage, skirting the Arctic Circle and avoiding the Royal Navy, to emerge in the Pacific to plunder British and Allied shipping,

Komet’s mission was an unlikely offshoot of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact—a cynical deal between Hitler and Stalin that triggered the outbreak of World War II. The pact, which stunned the diplomatic world on August 23, 1939, was much more than a pledge of mutual nonaggression. Secret clauses and side agreements amounted to a temporary limited partnership between the Nazi and Soviet dictators. At the outset, each got most of what he wanted.

For Hitler, the pact was a green light to invade Poland, now that he could be confident that the Soviets would not join Britain and France in the war against Germany. In a follow-on trade agreement, Moscow promised to supply Germany with vital raw materials, especially oil and grain—a hedge against a possible British naval blockade of Germany. The quid pro quo for Soviet raw materials was the promise of German military technology, particularly naval technology.

Stalin had grandiose plans for building a blue-water navy with enormous warships. In May 1936 he approved a naval construction program that featured an astounding 24 battleships and 20 heavy cruisers. The Sovetsky Soyuz-class battleships were to be 30 percent larger than the massive German battleship Bismarck. Construction had started on four of them before the plan was scuttled after the Germans invaded in June 1941. But it is estimated that Stalin’s battleship program consumed about one third of the defense budget in 1940.

In October 1939, while Berlin tried to get Moscow to agree to deliver the promised raw materials, Soviet officials arrived in Berlin with lists of German equipment they wanted. The Russians presented a 48-page list of requests, half of which were naval and included an entire heavy cruiser and destroyer, blueprints for the Bismarck, naval heavy guns, mines, torpedoes, and enormous amounts of construction equipment and precision machinery for shipbuilding. Not surprisingly, the Germans balked at the “voluminous and unreasonable” Soviet demands.

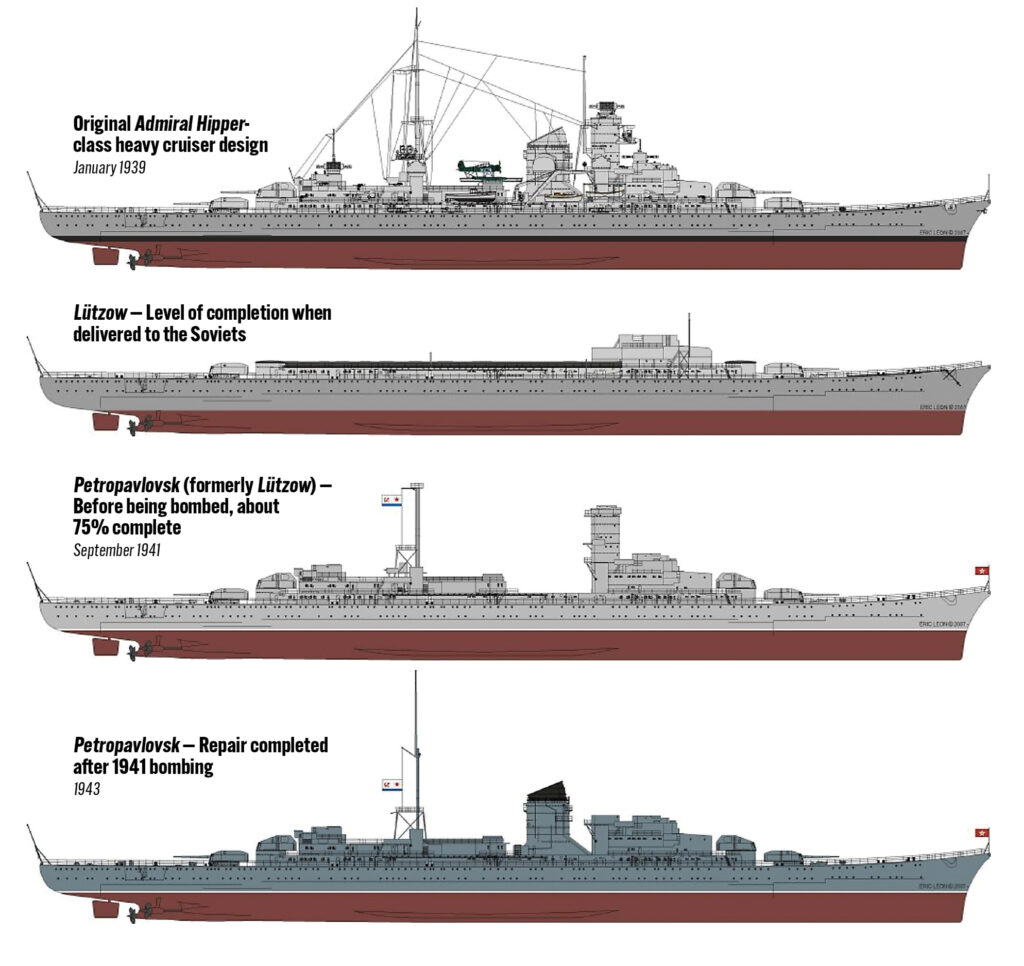

Eventually, Moscow began shipping large amounts of oil, grain, rubber, and other goods to Germany, although never in the quantity Berlin demanded. The Germans understood that in order to keep the Soviet supplies flowing, they would have to make good on some of their promises. At the top of the Soviet wish list was a heavy cruiser. Berlin decided to hand over the not-yet-completed cruiser Lützow, the newest of the Admiral Hipper-class. These were formidable warships, displacing more than 16,000 tons and mounting eight 8-inch guns in four turrets. The saga of the Lützow illustrates the promise—and the frustrations—of German-Soviet naval cooperation.

The Lützow was fitting out in a shipyard in Bremen in February 1940 when the transfer agreement was concluded. None of the 8-inch guns and only two turrets had been installed. Lützow eventually received four of the big guns in the fore and aft turrets. German tugs towed the ship through coastal waters and handed it over to Soviet tugs that towed the vessel the rest of the way to Leningrad. The Soviets renamed the cruiser Petropavlovsk.

The ship was still incomplete when it arrived. Besides missing half the main and all the secondary armament (twelve 5.9-inch guns), it had only a skeleton bridge, almost no superstructure above the first deck, and incomplete propulsion and mechanical elements. Over the next 12 months Germany was obliged to provide all these materials, plus detailed operating manuals and training for Soviet officers and crew. Even with the best of intentions on both sides, preparing the ship for sea was a daunting task and the project proceeded slowly.

The Soviets were eager in principle to get on with it, despite misgivings about sending enlisted men to Germany or allowing numerous German officers in Leningrad. But unknown to them, in December 1940 Hitler approved Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. From then on, German authorities went through the motions of preparing the training and completing the ship’s fitting out but dragged their feet at every turn.

In other areas, however, the prospects for naval cooperation seemed more promising. As early as October 1939, Moscow signaled its willingness to provide a harbor for German naval operations in northwest Russia in exchange for military technology. German Naval Warfare Command (Seekriegsleitung, orSKL) leaped at the possibility, since a base on the northwest Soviet coast would let German submarines and surface warships bypass the North Sea choke points patrolled by the Royal Navy. On October 17, the Soviets offered Zapadnaya Litsa, a remote harbor northwest of Murmansk in the Motovsky Gulf, the westernmost point of the Kola

Peninsula.

This harbor afforded good security as it was closed to both foreign and Soviet domestic shipping and its entrance could not be observed from the open sea. The German naval attaché in Moscow enthusiastically filled in SKL on the Soviet offer: “In this bay, Germany may do whatever she wishes; she may carry out whatever projects she should consider necessary. Any type of vessel may be permitted to call there (heavy cruisers, submarines, supply ships)…during any season of the year.” Despite some disadvantages—the harbor was totally undeveloped and isolated, with no naval facilities at all and no rail or road connections to the interior—SKL quickly accepted the offer and gave Zapadnaya Litsa the sensible code name Basis Nord (North Base).

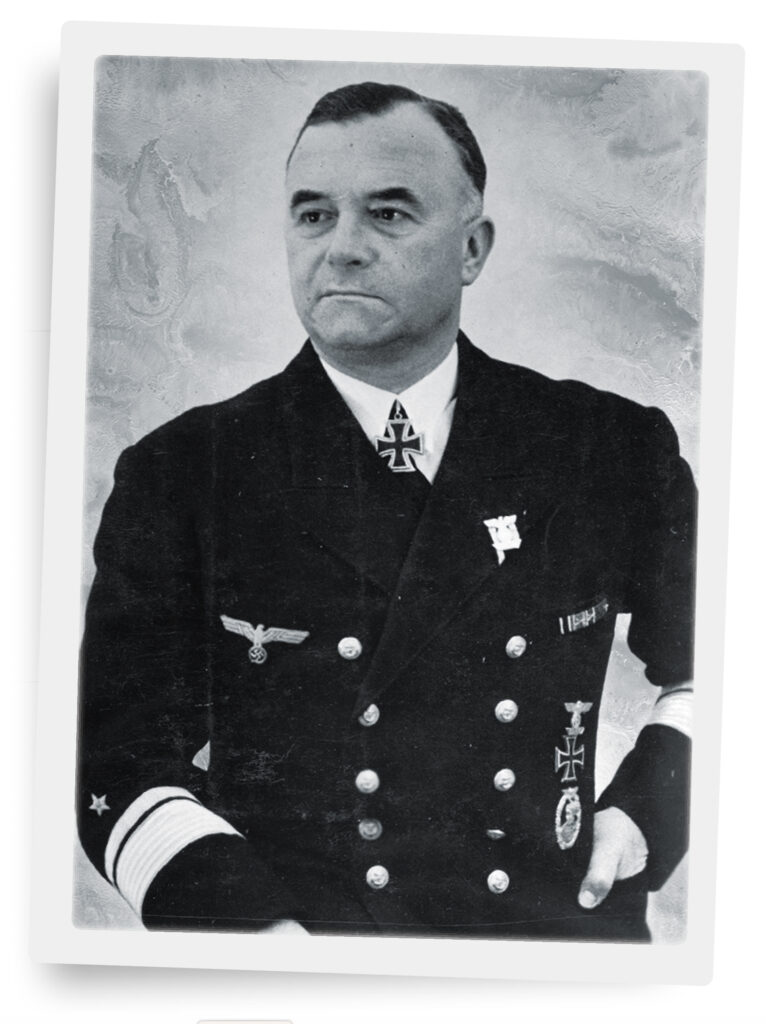

Basis Nord was to have three principal missions: as a logistics base for German warships, a safe harbor, and a repair base. Admiral Karl Dönitz, head of Germany’s submarine fleet, was especially interested, even though he anticipated being able to operate only one U-boat there at a time. Any possibility of Germany fortifying the base was out of the question. Security for Basis Nord would be entirely in the hands of the Soviet Navy.

Before making the base operational, Dönitz sent two submarines to evaluate the proposed base and the state of Soviet preparedness. This mission began inauspiciously, as the British submarine Salmon torpedoed and sank U-36 in the Norwegian Sea. Its sister ship, U-38, fared better. Its captain made a clandestine reconnaissance and reported that Soviet security and anti-submarine measures were excellent—so good, in fact, that he dared not attempt to follow a Soviet steamer through the anti-submarine nets in Kola Bay, a common tactic for German submariners.

SKL ordered several German merchant ships then trapped in Murmansk by the British blockade to proceed to Basis Nord, stocked with supplies to service German surface warships and submarines. Operationally, however, little was accomplished. Not only was the winter of 1940 exceptionally harsh, which hampered all naval activity in that northern region, but the Kriegsmarine was also stretched thin and had few vessels to spare for that theater, and Germany’s successes in Norway in April 1940 and a few months later in France provided the Kriegsmarine with bases that made Basis Nord totally unnecessary. Berlin ordered the base closed in August 1940.

But just as the book on Basis Nord was closing, a new chapter on naval cooperation between the not-quite allies was opening. In August 1940, the German auxiliary cruiser Komet was making its way through Russia’s ice-choked Northern Passage.

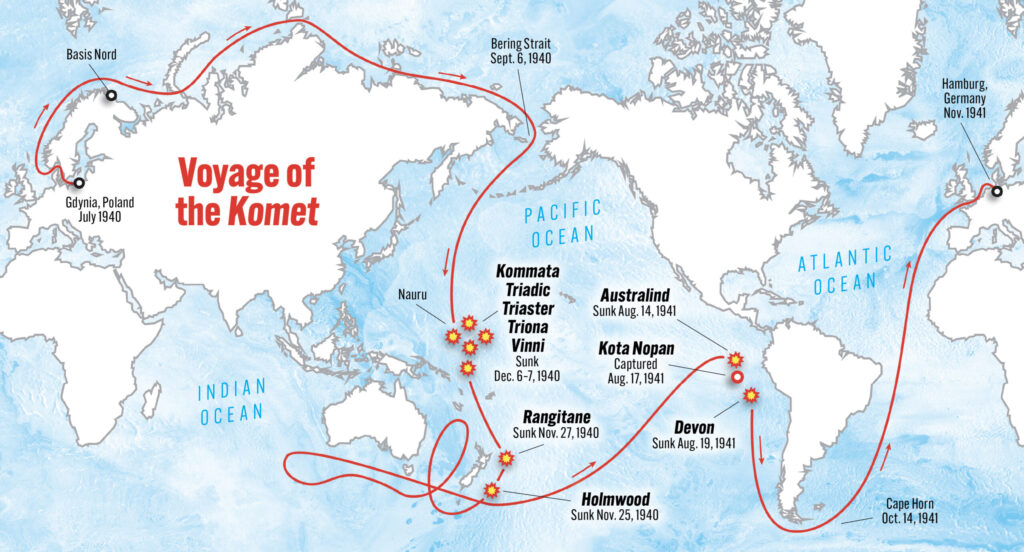

Komet began its journey, with Soviet permission, by steaming up the Norwegian coast disguised as a Soviet vessel. In early August, it took on two Soviet pilots to navigate the Arctic ice. The Soviet icebreaker Lenin guided Komet through several western Arctic Ocean passages. Using Soviet navigation and ice charts, Captain Eyssen and the pilots steered the ship through the Kara Sea and into the East Siberian Sea, where Komet encountered very thick ice that damaged and temporarily immobilized it. That’s where the icebreaker Stalin came to the rescue and led Komet far enough eastward that Eyssen, after disembarking the pilots, was able to complete the last few hundred miles of the voyage on his own. On September 6, Komet passed through the narrow Bering Strait separating Siberia from Alaska, and into the North Pacific. Eyssen had traversed the northern sea route in 23 days, the fastest crossing of the Northern Passage ever, up to that time.

Eyssen’s instructions were to hunt for enemy merchantmen in the southern waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, to lay mines in the approaches to Australian, New Zealand, and South African ports, and to seek out the Antarctic whaling fleets. SKL’s objectives were to disrupt enemy, especially British, shipping, and by so doing, tie down British naval forces in remote areas, relieving some of the Royal Navy’s pressure on German home waters.

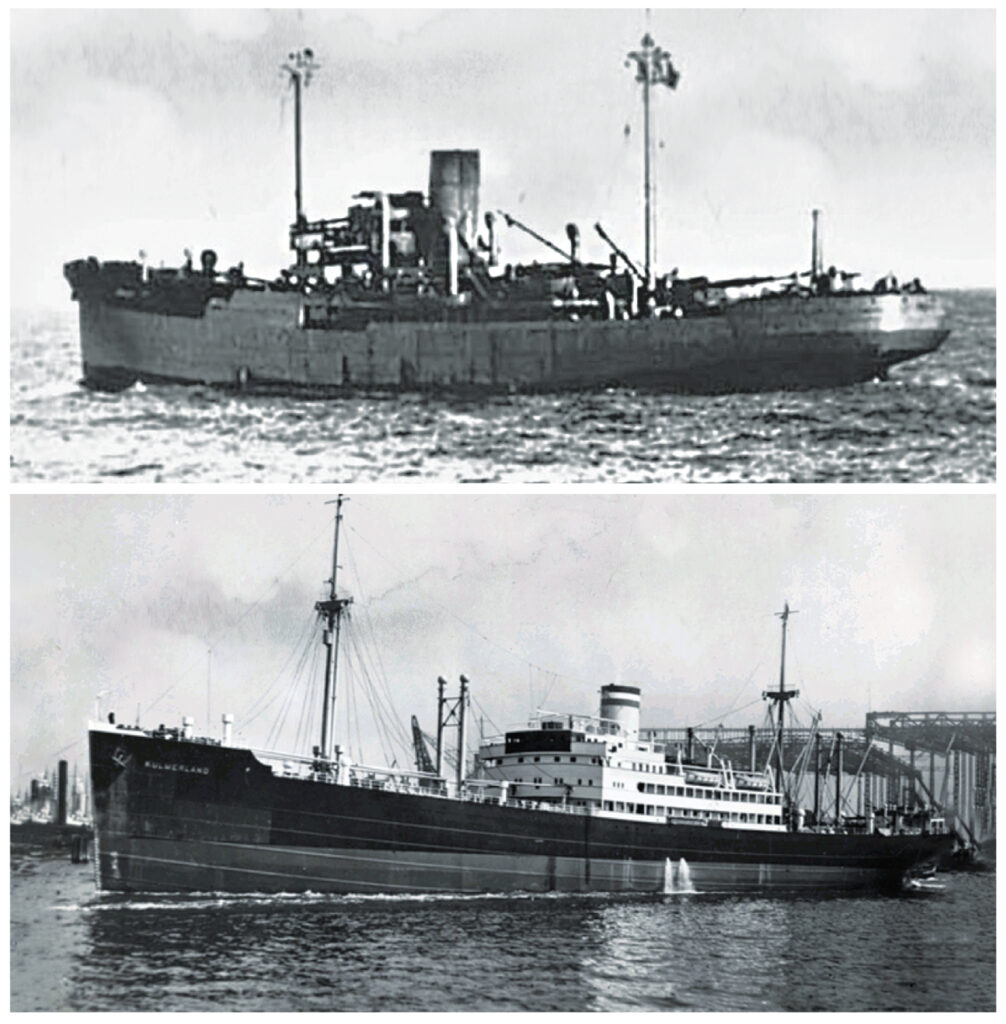

After refueling and topping off its supplies in Japan, Komet headed south. It reached the Caroline Islands without sighting a single enemy vessel. There, Eyssen rendezvoused with the auxiliary cruiser Orion and the unarmed freighter Kulmerland, a supply ship for the two raiders. All three took on the false identities of Japanese ships. Eyssen had the name Manyo Maru painted on Komet’sstern and likenesses of the Rising Sun flag emblazoned on the ship’s sides. No one on the Orion knew how to write its false identity in Japanese characters, so they copied some words from Japanese packaging found onboard and painted them on the ship’s side. Any observer who could read Japanese would have been surprised to find the ship operating under the unusual name Not Suitable for the Tropics.

Eyssen, the senior officer among the three captains, took his “Far Eastern Squadron” southeastward, cruising the sea lanes between New Zealand and Panama. On November 25, he found his first victim, the small New Zealand coaster Holmwood, which Komet sank with gunfire after first conveying its passengers and crew safely to Kulmerland and carrying off as many of the coaster’s cargo of sheep as the raiders could conveniently carry. At first the Germans were delighted with the fresh meat, but eventually they came to detest the taste of mutton.

Two days later, Komet and Orion caught a really big fish, the 16,700-ton New Zealand passenger liner Rangitane, bound from Auckland to Liverpool via the Panama Canal with 302 passengers and crew and large quantities of dairy and frozen meat as well as 45 bars of silver. The ship was relatively well-armed, with a 127mm and 75mm gun astern and several anti-aircraft guns on the bridge. It was also faster than the German ships. But the raiders hemmed Rangitane in before the crew knew they were enemy warships. After suffering a short, deadly crossfire at close range, the captain surrendered—but not before sending out an emergency radio signal that he was being attacked by German raiders. Captain Eyssen wanted a prize crew to sail the liner to Germany, not least because it would have been the largest prize ship ever taken by a German raider. But the distress signal Rangitane managed to send out had been picked up and re-transmitted to Australian and New Zealand naval units. Radio intercepts revealed that enemy warships and aircraft were on the way. The Germans hurriedly brought the passengers and crew aboard, sent the liner and its valuable cargo to the bottom, and fled northeast at top speed toward the island of Nauru. Two long-range New Zealand flying boats reached the scene later that day but found only floating debris.

Nauru lies roughly mid-way between Australia and Hawaii and is composed mainly of phosphate rock, a key ingredient in fertilizer. A joint British-Australian-New Zealand operation mined and exported that valuable commodity and Eyssen guessed correctly that he would find good hunting there. On December 6-7, Komet and Orion sank five freighters, four British and one Norwegian, in Nauru’s harbor and nearby waters. Several of the victims tried to flee, but a few well-aimed salvos compelled surrender, not without some loss of life on the freighters. Aside from that, all crew and passengers were brought on board the German vessels before their ships were destroyed. The captains of two of the British vessels thanked Eyssen in writing for “the way we have been treated on board your ship as prisoners. Everything possible has been done for us in the circumstances and…everything was done for the sick and wounded.” As acoup de grâce, after warning the civilians ashore of his intentions, Komet shelled the phosphate loading facilities on Nauru, putting them out of operation for months. Nauru did not resume full production until after the war.

The Nauru operation was the most successful and economically consequential action of Komet’s war cruise. In recognition, SKL promoted Eyssen to Konteradmiral (rear admiral). His new orders were to head south in hopes of catching the Anglo-Norwegian whaling fleet near Antarctica, and then to proceed into the Indian Ocean. Komet sailed alone, as Orion was slower even when not plagued with engine trouble, as it often was. Finding no sign of the whalers, Komet proceeded north again in March 1941 to patrol the waters between Australia and Africa. However, due to the high level of raider activity in the Indian Ocean, merchant shipping increasingly traveled in convoys under British naval escort. The following months were unproductive and frustrating for Komet. During this lull, Eyssen received the electrifying news that the Wehrmacht had invaded the Soviet Union in June. There would be no more transits of the Northern Passage for him—at least not until Russia was completely subdued.

SKL instructed Eyssen to return to Germany by October so Komet could be re-fit for its next war cruise. The new admiral was determined to score a few more victories on his way home and he was not disappointed. Near the Galapagos Islands on August 14, Komet’screw sighted the first enemy ship they had seen in seven and a half months. Still disguised as a Japanese vessel, the raider drew close before Eyssen had the Kriegsmarine ensign and his admiral’s pennant run up and he fired two warning shots. The 5,000-ton British freighter Australind, en route to England by way of the Panama Canal, refused to stop and its crew manned the 4-inch gun on the stern. At a range of only 3,000 yards, Komet rapidly put seven salvos into the British ship, severely damaging the bridge and killing the captain and another officer. The wounded ship stopped and lowered its boats. Eyssen brought the survivors aboard and, finding the cargo uninteresting, scuttled the ship.

Three days later, Komet intercepted the 7,300-ton Dutch freighter Kota Nopan, bound for New York. It was in good condition and carried a very valuable cargo of rubber, tin, and manganese. Eyssen put a prize crew aboard and, after a rendezvous with a supply ship to refuel Komet and his prize, he sent Kota Nopan toward home. It reached Bordeaux in November. Just two days after subduing Kota Nopan, another victim steamed into Komet’s view: the 9,000-ton British freighter Devon, bound for New Zealand with a “miscellaneous” cargo. Neither the ship nor its cargo was deemed worth saving, so after taking the crew aboard, Komet sunk the freighter with gunfire.

Komet rounded Cape Horn on October 14 and set a course for the French coast, taking on the identity of a neutral Portuguese freighter. It rendezvoused with two U-boats in mid-November and the submarines saw the raider safely into the Bay of Biscay. Komet anchored briefly at Cherbourg and Le Havre before making the dangerous dash up the English Channel, escorted by German torpedo boats and minesweepers. British torpedo boats and bombers attacked; a bomb caused minor damage but no casualties. Spending a day in Dunkirk, Komet continued up the coast of Holland and, at 6:00 p.m. on November 30, 1941, tied up at Hamburg. Komet had been at sea for 516 days, sailed over 87,000 miles, crossed the equator eight times, sank seven ships and sent one home as a prize, and wrecked the phosphate operations at Nauru. It had been an epic voyage.

Komet laid up for almost a year for a complete re-fit that included overhauling the engines and receiving new guns and upgraded communications gear in preparation for a second war cruise. This time there would be no Northern Passage; Komet would have to get past the Royal Navy to reach the Atlantic. Admiral Eyssen was ashore in Norway as chief of the Oslo Naval Depot. Komet was now commanded by Captain Ulrich Brocksien, who took the raider out offriendly waters on October 7, 1942, and docked in Dunkirk that night. On October 12, Brocksien made his break for the open sea, escorted by four torpedo boats. But the Royal Navy, forewarned perhaps by an Enigma radio decrypt, was ready and had two British battle groups, composed of eight destroyers and eight torpedo boats, waiting.

An RAF patrol plane spotted Komet around midnight and dropped flares. The British ships attacked. In the melee that followed, Komet was hit and set afire. The flames spread rapidly and minutes later a massive explosion sent a fireball hundreds of feet into the night sky and literally blew the ship apart. Komet sank immediately, taking all 251 officers and men with it. In after-action reports, the British attributed Komet’sdestruction to one or two torpedo hits. German torpedo boat officers saw no torpedo wakes near Komet and believed gunfire from the destroyers must have scored a direct hit on one of the ammunition magazines.

While Komet was dying, Petropavlovsk, the former German heavy cruiser Lützow, lived on. When the Wehrmacht stormed into the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Petropavlovsk was not seaworthy but could serve as a deadly floating artillery battery. Tied up at the coal wharves in Leningrad harbor in early September, the cruiser poured some 700 rounds from its 8-inch guns into German forces closing in on the city. German troops attested to the fearsome impact of those shells. On September 17, German heavy artillery scored multiple hits on the ship, which sank bow first. Soviet salvage crews managed to raise it sufficiently to get its guns back in action a year later. The Soviets renamed the ship Tallinn in September 1944 when an old Tsarist-era battleship received the name Petropavlovsk. Tallinn hit the Germans again during the breakout from Leningrad’s encirclement in 1944. The fighting soon passed beyond the range of its guns, which finally fell silent.

After the war, the Soviets used the battle-scarred hulk as a floating barracks until it was broken up for scrap in the 1950s. That ended the last physical remnant of wartime German-Soviet naval cooperation.