It had taken two battles, near constant artillery bombardment and massive airpower, but the combined forces of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) and Soviet Union were finally poised to take the key Mujahideen logistics base at Zhawar on a relatively cool April 19, 1986. The Mujahideen had masterfully utilized local topography to carve out their base of operations against the communist DRA and its Soviet backers, and Zhawar had become a key strategic objective as both sides fought for control of Afghanistan amid the 1979–89 Soviet-Afghan War.

By 1979 widespread rebellion had engulfed broad swaths of Afghanistan, countered by a commensurate increase in Russian intervention on behalf of the pro-Soviet government. DRA General Secretary Hafizullah Amin’s grip on the country was on the verge of collapse. His primary control mechanism, the Afghan army, was a mere shell of what it once was, having dropped from a high of around 100,000 troops to less than half through desertions and internal combat operations. The Soviets, by contrast, had more than 8,000 troops and 1,500 advisers on the ground, with tens of thousands more poised for intervention in order to prevent the collapse of Amin’s administration. The time had come for the Russians to take control of the situation and, in their minds, stabilize the country.

Direct Soviet intervention began that Christmas Day when the 40th Army and supporting air units crossed into Afghanistan. Two days later the Russians landed more than four divisions at Afghan airports. In the capital city of Kabul their assault troops engaged in especially fierce fighting with troops loyal to Amin. Though suffering heavy casualties, the Soviets eliminated the guards at the outlying Tajbeg Palace before executing Amin, all of his male family members and members of his inner circle. By day’s end they’d installed their chosen puppet, Babrak Karmal, as DRA general secretary.

The invasion, the toppling of Amin (who, though not exactly beloved by Afghans, was still their leader), the installation of a puppet ruler and the presence of a Soviet occupation force was too much for many of the fiercely independent Afghans. Within months the Mujahideen joined forces with thousands of Afghan army deserters to take up fierce armed resistance throughout the country, especially in rural locales. A panicked Karmal beseeched the Soviets for more military assistance, which promptly flooded into the country, raising the Soviet troop count to 105,000 in short order. The long, bitterly contested struggle for Afghanistan ensued.

Fast forward five years. By 1985 the Mujahideen enjoyed widespread support from rural Afghans, while the puppet government and its Soviet backers held sway in the major cities. The Mujahideen put their efforts into hit-and-run attacks on Soviet and DRA convoys, supply lines and communications, while the Russians sought to deprive the rebels of their logistics, supplies and food by ruthlessly bombing and destroying villages, food stores, crops and even animal herds. The Soviet dictum was to “kill the fish by draining off the water.”

To counter such efforts the Mujahideen established a nationwide network of supply bases and depots to serve as logistical hubs for their operations. Among the more hotly contested such sites was Zhawar. On the central-eastern border a scant 15 miles from the Mujahideen’s supply hub at Miran Shah, Pakistan, Zhawar became a primary center for rebel operations and a major thorn in the side of the Soviets and DRA. Literally blasted and carved from the base of Sodyaki Ghar mountain, the base comprised 41 caves linked by 11 major tunnels extending up to 500 yards underground. The extensive facility included a hotel (used by visiting Western journalists), a mosque, a weapons depot, a medical station, a radio hub and a garage housing, among other vehicles, two captured Soviet T-55 tanks.

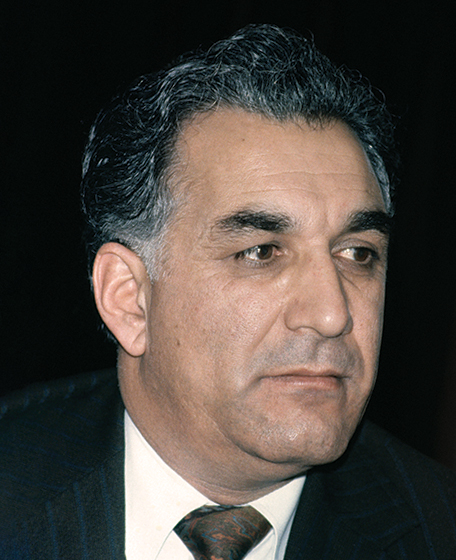

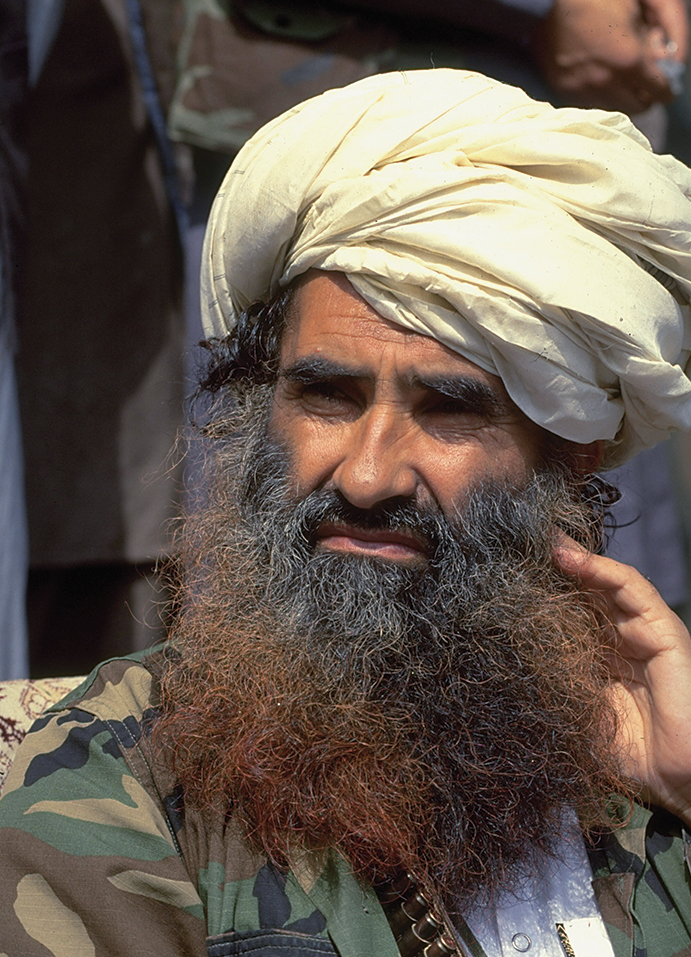

Zhawar served as a supply base for area Islamic Party (HIK) groups, and its garrison policed checkpoints along the border to identify and prevent infiltration by KHAD (Afghan intelligence) and KGB agents. Commanded by provincial Mujahideen leader Jalaluddin Haqqani, it was garrisoned by the 500-strong Zhawar Regiment and outfitted with, in addition to the pair of T-55s, a Soviet D-30 122 mm howitzer, several Chinese BM-12 ML 102 mm multiple rocket launchers and an assortment of machine guns and small arms. Deployed on the surrounding high ground was an air defense company equipped with five ZPU-1 and four ZPU-2 14.5 mm anti-aircraft guns.

This substantial logistics hub handled more than 20 percent of the supplies powering the Mujahideen war effort, thus it represented a valuable asset for the rebels and a prime target for the DRA and Soviets. In September 1985 the latter moved to take out the base in what became known as the First Battle of Zhawar.

That fall the DRA 12th Infantry Division, along with elements of the 37th and 38th Commando brigades, moved out from Gardez and took a circular route to Khost to avoid the Mujahideen-controlled direct route through the Khost-Gardez (aka Sata-Kandow) pass. Joining up with the 25th Infantry Division at Khost, the column coalesced into a composite force (due to strength deficiencies). In early September the DRA infantry, under the command of Lt. Gen. Shahnawaz Tani, with supporting artillery fire and targeted air strikes, struck rebel positions northeast of Zhawar at a place called Bori. As Haqqani and most of Zhawar’s top commanders and field officers were away on hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) and thus unprepared for such a strike, Bori quickly fell to the DRA, who pushed on toward Zhawar.

On learning of the fall of Bori, the Mujahideen deployed an 80-man blocking force along the eastern slope of Moghulgai Ghar, which formed the eastern perimeter of Zhawar. The DRA force arrived outside the base under cover of darkness, only to be immediately engaged by defenders and lose two armored personnel carriers and four other trucks. The dispirited DRA force ultimately withdrew to Khost, allowing the Mujahideen to reclaim Bori.

The DRA force next attacked and captured the town of Lezhi, killing its Mujahideen commander. That same day, September 4, Haqqani and other high-ranking rebels returned to Zhawar and took command of the situation. While the Mujahideen from Lezhi withdrew south, a force of 20 rebels deployed to block Manay Kandow pass.

Manay Kandow was a natural fortified position, with high peaks and a thick rock slab cap that could shelter up to a couple dozen troops from shelling and air strikes. The Mujahideen had also dug defense and communications trenches with clear views of the exposed Tani plain below. The DRA presumptively launched its infantry straight at the Mujahideen positions, only to be turned back by withering fire. Making no progress against the entrenched Mujahideen, the DRA called in massive air strikes and artillery bombardments and then sent in the infantry once again. It repeated this cycle for 10 straight days with no gains before calling on its Russian allies for heavier, sustained air bombardments. Under the continuous pounding of Soviet air strikes, fearful the cave would collapse on them, the Mujahideen finally pulled out on September 14, allowing the DRA to move in and occupy the high ground.

That tactical gain in turn allowed the DRA to refocus its air strikes and bombardments against Zhawar while its infantry moved through the pass. The Mujahideen rear guard contested the crossing as well as they could, but they lacked the numbers and necessary firepower and slowly gave way. Eventually the DRA pushed through and gained the high ground of Tor Kamar, little more than a half mile from Zhawar. Assuming victory was at hand, the DRA carelessly grouped its forces on the high ground in preparation for the final push.

A surprise was in store for them, as the supposedly cowed Mujahideen counterattacked, its two captured T-55s emerging from their subterranean garage to open fire on the grouped government ranks. Moving from position to position, the tanks sent soldiers flying and stunned their officers, who had no idea the Mujahideen had any heavy weapons, let alone tanks. The ravaged DRA forces fled in panic, the Mujahideen throwing up blocking positions wherever possible to continue hammering them at every step.

After 42 days of fighting and the loss of a helicopter and untold numbers of government troops (statistics vary, but casualties were presumed to have been heavy), General Tani ordered a nighttime withdrawal of his men. Faulty to nonexistent intelligence on the part of the DRA had cost it the battle, as the lack of a properly prepared defense nearly had for the rebels. It proved a tactical victory for the Mujahideen, at the expense of 106 killed and more than 300 wounded. More important, it reaffirmed their control of the country and perceived invincibility in the hinterlands. But the DRA would try again in a few short months, this time with direct and substantial Soviet assistance.

In February 1986 Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev announced the signing of an agreement with the Afghan government for the planned withdrawal of Soviet troops, while simultaneously strengthening the DRA ranks in order for it to assume the leading combat role. Meanwhile, the Soviet High Command urged the DRA Ministry of Defense to take the fight to the Mujahideen and destroy the base at Zhawar.

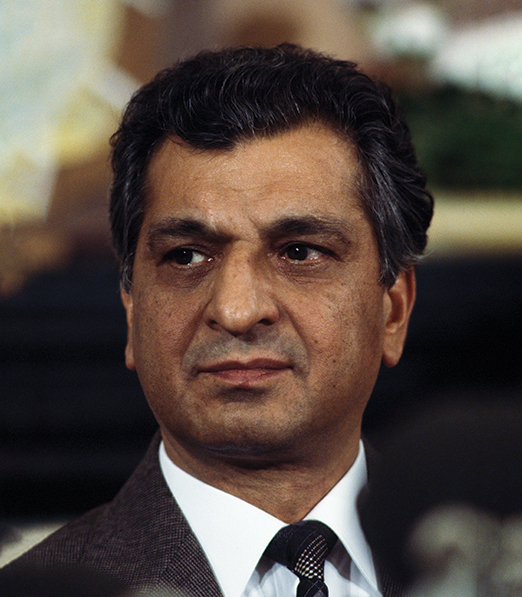

The DRA committed 54 battalions (nearly all understrength), artillery and air support to the operation. The 7th, 8th, 14th and 25th infantry divisions, the 38th Commando Brigade and the 666th Air Assault Regiment—close to 12,000 troops—would constitute the DRA army tasked with taking Zhawar. This time the Afghans would be operating with the direct Soviet assistance of more than 2,000 troops from the 1st and 3rd battalions of the 191st Separate Motorized Rifle Regiment. The operation was led by Lt. Gen. Nabi Azimi, with Soviet Maj. Gen. V.G. Trofimenko serving as his combat advisor. On February 28 DRA and Soviet forces moved out of their staging grounds at Gardez toward Zhawar.

After nearly a month of painstakingly slow progress hampered by wet snow, driving rain and shelling by the Mujahideen, the DRA force made its way into the Khost valley in preparation for the offensive on Zhawar. The initial assault began at around midnight on April 2 with a two-hour artillery barrage, followed by an airborne insertion of elements of the 38th Commando Brigade via six Mil Mi-8 transport helicopters in conjunction with an attack by the 7th and 14th infantry divisions in the east and the 8th and 25th infantry divisions in the west.

The airborne insertion itself was a disaster, as it was discovered around 3 a.m. that paratroopers had overshot their objective and ended up a few miles inside Pakistan, where they were soon surrounded and captured. Regardless, Azimi ploughed ahead with the main assault. After an initial strike against Mujahideen positions by Sukhoi Su-25 attack aircraft, 15 transport helicopters inserted the remaining units of the 38th Brigade across seven landing zones. Next came the infantry attack, meant to link up with the already destroyed air assault forces. In their absence, intense fighting soon raged at every landing zone, and Mujahideen troops took out helicopter after helicopter. To quell their accurate fire, field officers called in Soviet jets to bomb and strafe rebel positions, against which the latter’s defenses proved largely ineffective.

The Mujahideen remained undeterred. Led by Haqqani, who with dozens of other rebels had managed to escape a collapsed cave, more than 700 Mujahideen emerged from concealment to attack the landing zones, overrunning four of them. The timely arrival of rebel reinforcements from the Pakistani border caught the DRA forces in a tactical vise, leading to the capture of more than 500 commandos of the 38th Brigade by day’s end.

After three days of combat, counting both casualties and men captured, the 38th Brigade had been effectively destroyed, as had two dozen of its 32 transport helicopters. The conduct of the operation had proven so abysmal that the Soviets were compelled to assume direct command, tasking General of the Army Valentin Ivanovich Varennikov with turning things around.

The Soviet general immediately buttressed available forces, bringing in three additional DRA regiments, a DRA spetsnaz (special forces) battalion and six Soviet battalions before resuming the offensive. During the 12 days Verennikov was granted to prepare his assault, Soviet/DRA artillery and air strikes continued around the clock. With the launch of the renewed effort on the morning of April 17, the artillery and air units stepped up the intensity of their fire support. DRA infantry then hit the Mujahideen from both east and west. After several staggered assaults and a tactical adjustment—in which Afghan government troops moved to high ground under cover of darkness and assaulted without a preemptive artillery strike—the Mujahideen faltered and withdrew from the heights of strategically important Dawri Gar.

Several events had transpired to turn the tide for the DRA troops and their Soviet backers. First, during the fight for Dawri Gar and that of greater Lezhi a critical Mujahideen unit had suddenly and unexpectedly withdrawn without having fired a shot. Around the same time an air strike had wounded Haqqani. But as that news was relayed down the line, a rumor spread he’d been killed. Word their popular leader was dead was enough to prompt the discouraged rebels to evacuate Zhawar. Emerging with the two captured T-55s, a rear guard held off the enemy long enough for the main body to flee into the mountains. Amid the hasty pullout the Mujahideen left behind most of their equipment and supplies, while they abandoned the tanks in the foothills. After months of expended blood, sweat, toil and munitions, DRA and Soviet forces finally claimed Zhawar at noon on April 19.

They wouldn’t remain long, as intelligence indicated that Mujahideen along the Pakistani border were already mobilizing multiple rocket launchers in preparation for a counterattack. Time being short, the occupiers were given but four hours to destroy the complex—far from enough time to do an adequate job. Communist sappers detonated several hundred antitank mines in the primary caves, doing what little damage they could, before pulling out before dark.

The Second Battle of Zhawar had proved both a short-lived and costly victory for the DRA and its Soviet backers. In addition to their presumed heavy casualties, more than 500 of their men had been captured, and they’d lost two dozen helicopters and two attack jets. By comparison the Mujahideen had lost 281 killed and some 350 wounded. Adding insult to injury, the minute DRA and Soviet forces abandoned Zhawar, the Mujahideen moved right back in to repair the damage, improve defenses and bring the base back up to operational status within weeks. The reconstituted rebels subsequently filtered back into the region, reclaiming all areas previously taken by DRA and Soviet troops.

The collective Battles of Zhawar were to have been a showcase for the Afghan government, an opportunity for it to establish its legitimacy as the governing body of its fractured nation. Instead, its poor handling of the offensives cost it dearly in manpower and materiel. The fiasco also put the Soviets in a lose-lose position even as they prepared to transition out of the country. While Russian firepower had given the DRA the edge it needed to capture Zhawar, Afghan intelligence had failed to properly assess enemy defenses and strengths, to its own detriment.

To be fair, the Mujahideen were also wracked with intelligence failures. Their spies had failed to identify the DRA-Soviet buildup for the second battle. Then, at the height of combat, Haqqani’s rumored death exposed weaknesses in the rebel command-and-control structure, costing the Mujahideen their supply base, albeit only briefly.

In the end, the seesaw struggle for Zhawar accomplished little, though the battles did reaffirm for the Afghan people and the international community that the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, or any such puppet government, could not defeat the Mujahideen without the direct military intervention of its backers. The Soviet Union could have taken that lesson from history. Instead, they learned by hard experience. By then the communist superpower had had enough of the “graveyard of empires.”

Michigan-based Michael G. Stroud is a frequent contributor to military history publications and websites in both the United States and Britain. For further reading he recommends The Other Side of the Mountain: Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet-Afghan War, by Ali Ahmad Jalali and Lester W. Grau, and The Soviet-Afghan War: How a Superpower Fought and Lost, by the Russian General Staff, edited and translated by Lester W. Grau and Michael A. Gress.

This story appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.