Riding the bus from his Harlem boardinghouse to his new job in downtown Manhattan on a frigid February day in 1918, Walter White skimmed the morning papers until he came to a headline that read “Negro Burned at Stake.” The accompanying article was short but horrific:

“Estill Springs, Tenn. Feb 12—Jim McIlherron, a negro who shot and killed two white men here last Friday, was burned at the stake here tonight after a confession had been forced from him by application of red hot irons…The prisoner was taken out of town, chained to a tree, tortured until he confessed, implicating another negro, and then was burned.”

White showed the article around the office. Two weeks earlier, he’d taken a job as assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a nine-year-old civil rights organization. What, White asked his bosses, would the NAACP do about this grisly murder?

The group’s usual response to lynchings—dozens occurred every year—was to send a telegram of protest to state officials, followed by an angry press release. White, 24, had another idea. He volunteered to travel to the scene of the crime in rural Tennessee to uncover the full story so the NAACP could reveal all the grisly details to the American public.

His bosses thought that was crazy. A Black man arriving in a small southern town to investigate a lynching was liable to get lynched himself.

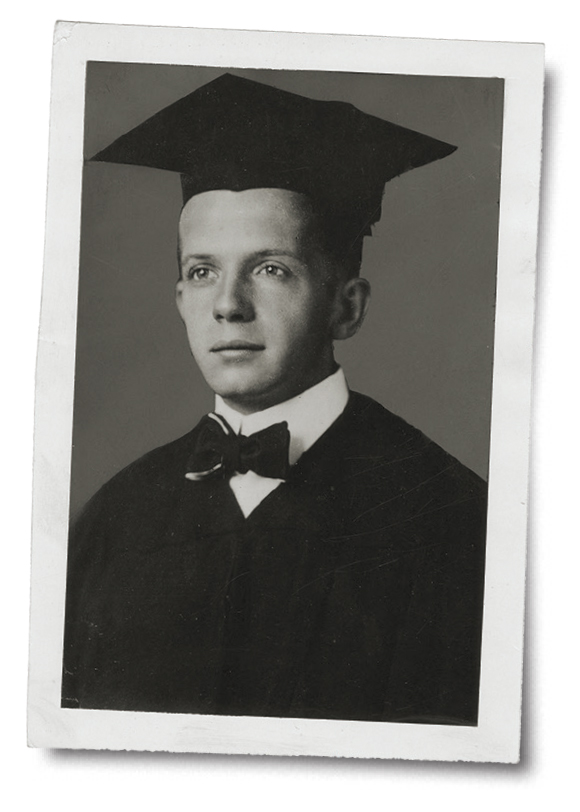

But White persisted, arguing that he was perfect for the task. Although he was Black and had attended segregated Black schools from first grade through college in his native Atlanta, he had light skin, blue eyes, and straight brown hair, legacies of many Caucasian ancestors. He could easily pass for White, White argued, and on a previous job selling insurance he’d traveled around Georgia, so he knew how to get along with rural southerners, Black and White.

A born salesman, White sold his bosses on his idea. Two days later, he boarded a train for Tennessee. The man who had signed up for a comfortable desk job in the NAACP’s Fifth Avenue headquarters spent much of the next decade as an undercover detective, traveling the United States of America to investigate and chronicle more than 40 lynchings and race riots.

White stepped off a train in Estill Springs, where Jim McIlherron had been killed, and rented a room in a White boardinghouse, telling the desk clerk he was a salesman for the Excelsior Medicine Company. He wandered to the general store where, he guessed, folks would be huddled around a potbelly stove, trading gossip. He was right, so he introduced himself, remarked on the weather, and sat down to chat.

Mentioning the Jim McIlherron matter would have aroused suspicion. When his new companions brought up the lynching, White pretended he’d never heard of it, then changed the subject. His feigned indifference only increased their eagerness to talk about the most exciting event they’d ever seen, and they soon were recounting the story in horrifying detail.

“By waiting for them to bring up the subject, which I knew would be inevitable, and by cautious questioning, I got all the information I needed,” White explained that evening in a letter he sent to his NAACP bosses. “Will tell story in detail when I return to office.”

White told the story in a shocking article for The Crisis, a 100,000-circulation NAACP monthly that famed Black scholar W. E. B. DuBois edited. Jim McIlherron had not been popular with Whites around Estill Springs, White wrote. A prosperous Black farmer who had lived awhile in Detroit, Michigan, McIlherron was disinclined to defer to Whites. On February 8, 1918, he came to town and bought 15 cents worth of candy. As he was strolling down the street eating it, three young White men began pelting him with rocks. “Rocking” Blacks was a common amusement among Whites in Estill Springs, but McIlherron was not amused. He pulled a pistol and fired, killing two of the rock throwers.

McIlherron returned to his home, which he then fled on a mule, stopping at his minister’s house. A mob that had been chasing him shot the minister dead. McIlherron escaped, but not for long. Two days later, a posse captured him and brought him to Estill Springs, where more than 1,000 Whites had gathered.

“McIlherron was chained to a hickory tree,” White wrote. “Wood and other inflammable material was saturated with coal oil and piled around his feet. The fire was not lighted at once, as the crowd was determined ‘to have some fun with the damned n——’ before he died.”

White men heated iron bars in a fire until the ends glowed red, then pressed them against McIlherron’s neck and thighs. After 20 minutes of this torture, somebody used a red-hot iron bar to castrate McIlherron. He begged his tormenters to shoot him, but they refused, saying, “We ain’t half done with you yet, n——.’

“By this time, however, some of the members of the mob had, apparently, become sickened at the sight and urged that the job be finished,” White wrote. “Finally, one man poured coal oil on the Negro’s trousers and shoes and lighted the fire around McIlherron’s feet. The flames rose rapidly, soon enveloping him, and in a few minutes McIlherron was dead.”

Not long after White’s gruesome story appeared in the May 1918 issue of The Crisis, its author headed to Georgia to investigate a series of lynchings even more horrible. Again posing as a salesman, White learned that the violence had arisen from Georgia’s infamous “convict leasing” system. Poor Blacks who had been convicted of minor crimes got a choice: pay a fine or go to jail. White landowners needing laborers would pay the fine if the convict agreed to work off the debt, a process that could take years. When Sidney Johnson, who was Black, was arrested for gambling and fined $30, Hampton Smith, owner of a plantation near Valdosta, paid Johnson’s fine and worked him for months. When Johnson insisted he’d paid his debt, Smith beat him up. Two days later, Johnson shot Smith dead.

When news of the killing spread, a mob searched for Johnson without success. Frustrated, the revenge seekers hunted other Blacks known to have quarreled with Smith over working conditions. On Friday, May 17, a mob lynched two Black men, then fired hundreds of bullets into their corpses. That Saturday, mobs lynched three Black men and left their bodies hanging from trees. On Sunday, Mary Turner—eight months pregnant and widow of a mob victim—demanded that police arrest her husband’s killers. Irate, a mob hung Turner upside down, soaked her clothing in gasoline, and set it afire. As she was writhing in agony, a man sliced the fetus from her womb with a carving knife and crushed it beneath his shoe.

“I shall never forget the morning when I stood where Mary Turner was killed,” White wrote in a letter, “her grave marked by an empty quart whisky bottle with the stump of a cigar stuck in its mouth.”

White spent three days in the area, first listening to White folks’ accounts of the lynchings then circulating among Blacks, identifying himself as an NAACP worker and hearing their stories. Later, he posed as a reporter for the New York Post—Post publisher Oswald Garrison Villard, a member of the NAACP board, had given him credentials—and interviewed Georgia’s governor, Hugh Dorsey, who denounced mob violence. But no one was ever arrested for the murders.

The NAACP publicized White’s findings and newspapers published angry editorials. The outcry convinced President Woodrow Wilson, no friend of Blacks or of civil rights, that lynchings were undermining his efforts to portray America’s war with Germany as a moral crusade to “make the world safe for democracy.”

“Every mob contributes to German lies about the United States,” Wilson wrote in an anti-lynching proclamation in July 1918. “Every American who takes part in the action of a mob or gives it any sort of countenance is no true son of this democracy, but its betrayer.”

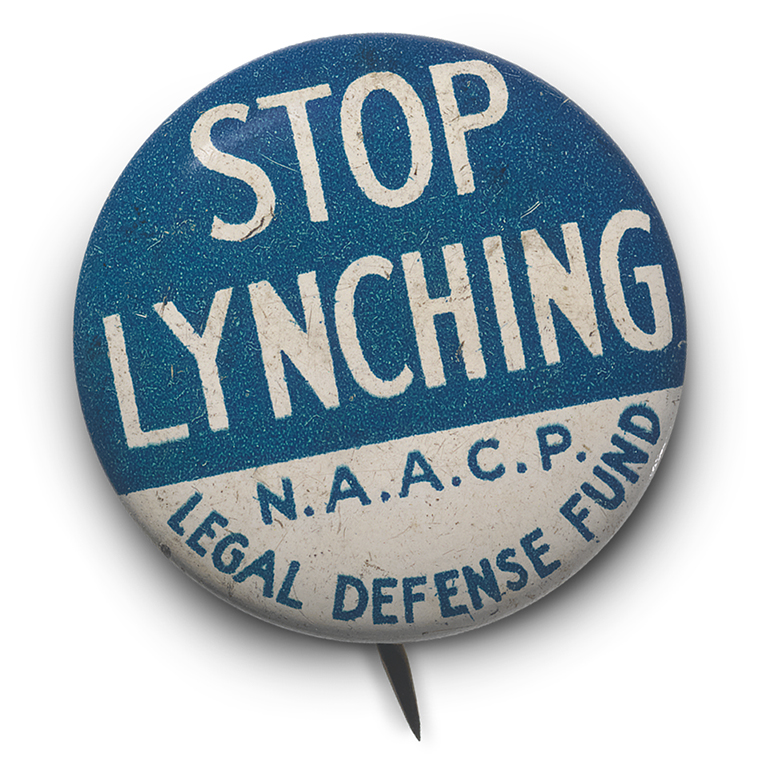

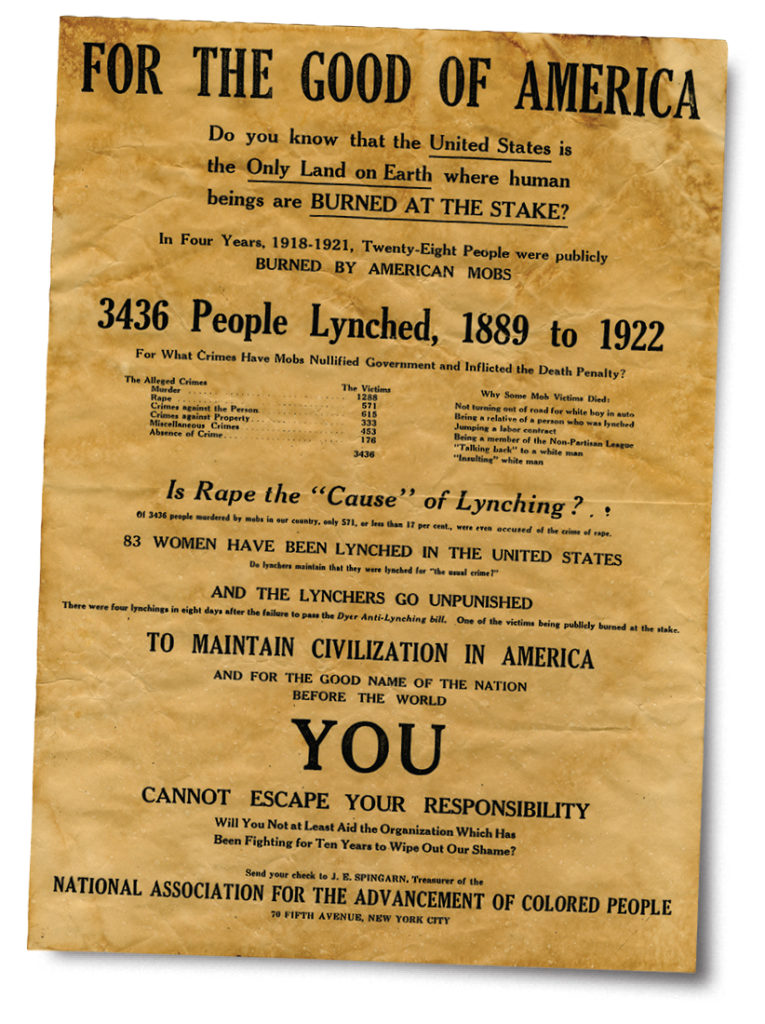

Wilson’s words were welcome; a presidential proclamation, however, had no legal power. Determined to pass and enact a federal anti-lynching law, John Shillady, head of the NAACP, dispatched White to Washington to lobby for a bill to make lynching a federal felony. Despite the NAACP’s efforts, the proposal languished for years. In 1922, the House of Representatives passed an anti-lynching measure. Southern senators killed the proposed legislation with a filibuster. Filibusters dispatched anti-lynching bills in 1935, 1938, 1948, and 1949.

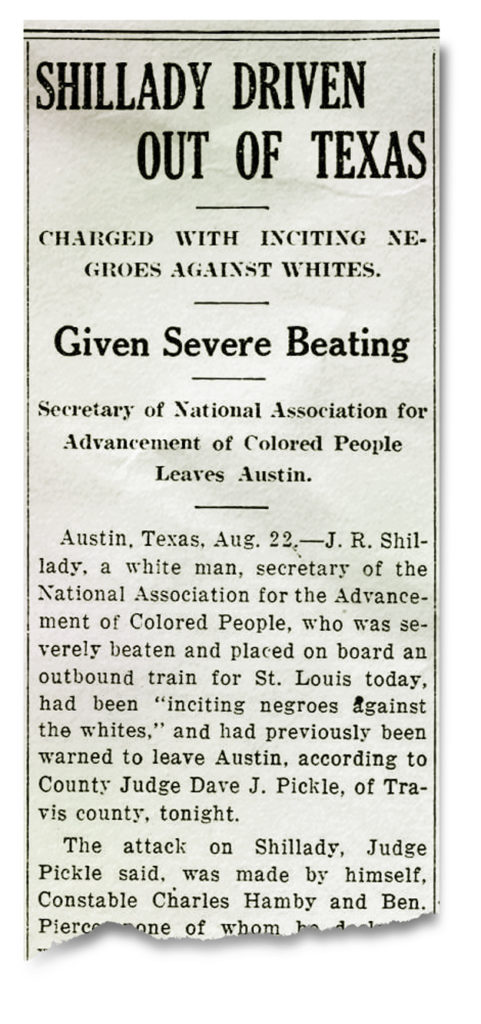

In 1919, the attorney general of Texas announced that the NAACP could not operate in his state because the organization was not chartered in Texas and because its opposition to segregation violated Texas law. When John Shillady, the NAACP’s White executive secretary, traveled to Austin to meet the attorney general, eight men, including a local judge and two policemen, brutally beat him in broad daylight and put him on a northbound train. Texas Governor William Hobby defended the assault, calling Shillady a “narrow-brained, double-chinned reformer” guilty of “stirring up racial discontent.” Shillady never recovered. After several hospitalizations and brief attempts to return to work, he resigned. He died a year later.

White watched his boss’s deterioration with horror. He knew he might meet a similar fate any time he investigated a lynching. But he persisted, traveling thousands of miles year by year to uncover and tell the stories behind racist mob terrorism.

“With his keen investigative skills and light complexion,” White’s biographer, Kenneth Robert Janken, wrote, “Walter White had proven to be the NAACP’s secret weapon against white violence.”

In 1919, White traveled to Shubata, Mississippi, to investigate the killing of four Black farmworkers, two of them young women. “The white people would not talk very much about the matter,” White wrote in a letter to headquarters, but a Black preacher and a cousin of the female victims told him the sordid backstory.

All four victims worked on a farm owned by a White dentist who had impregnated both women, sisters Maggie and Alma Howze. One of the male victims, Major Clark, had begun dating Maggie Howze.

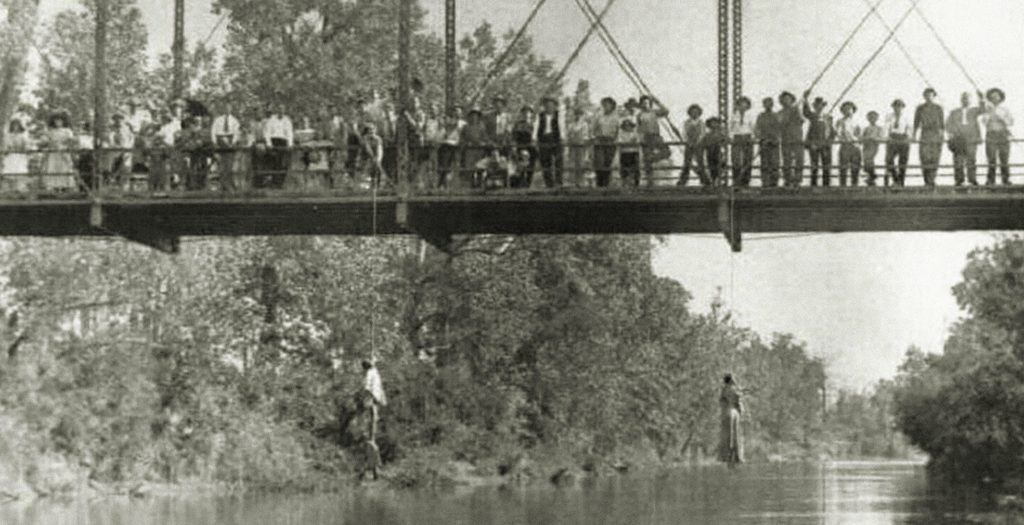

That angered the dentist, who ordered Clark to end the relationship. When the dentist was murdered, police arrested the Howzes, Clark, and his 15-year-old brother, Andrew. At a police station, cops stripped Clark, put his testicles in a vise and squeezed them until he confessed. A trial was scheduled, but never occurred because a mob dragged all four suspects out of jail and hanged them from a bridge over the Chickasawhay River.

“It will do great good,” White wrote to his bosses, “to let the world know that such a thing can and does happen in America.”

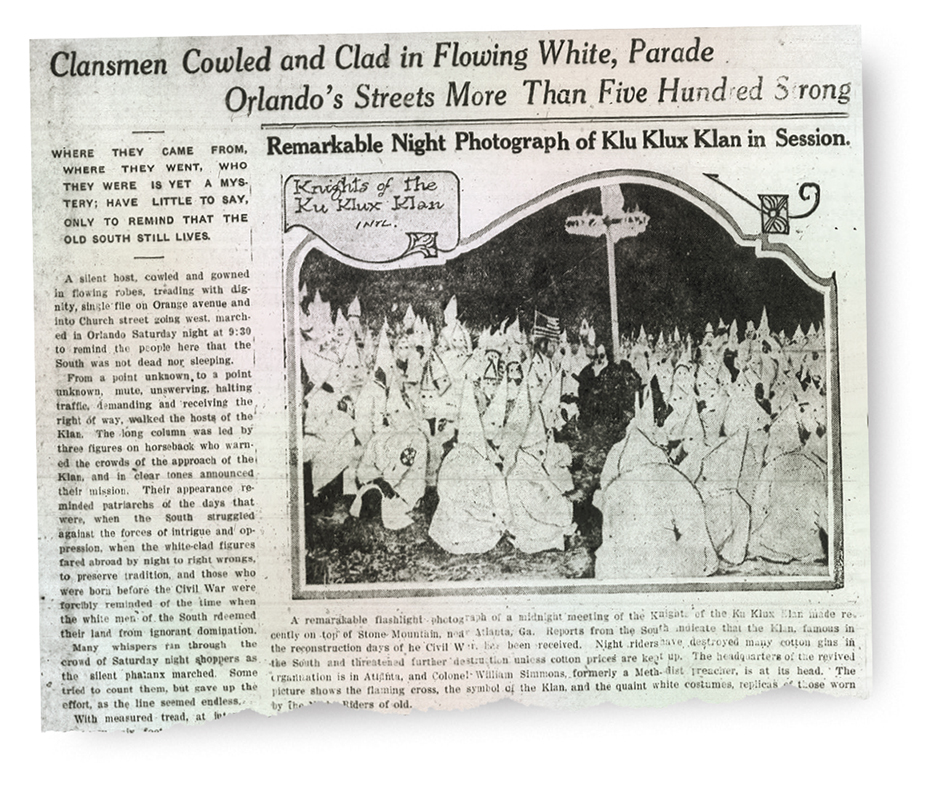

In 1920, White traveled to Ocoee, Florida, a citrus-farming town near Orlando. A few days before, on Election Day, a White mob, angered that a black man had attempted to vote in the presidential election, had put a Black neighborhood in Ocoee to the torch.

“I was regarded with very great suspicion,” White wrote in his report, “until I let it be known that I might be in the market for an orange grove.” Seeing dollar signs, White residents showed him farm properties and talked about the riot. Weeks before Election Day, the local Ku Klux Klan had proclaimed that no Black people would be allowed to vote. When Moses Norman, a prosperous Black citrus farmer, went to the polls, a White mob attacked him.

Norman fled to the home of a friend, Julius Perry. The mob surrounded Perry’s house and set it aflame. Then the rioters burned the rest of the neighborhood, incinerating 20 houses, two churches, and a school, shooting Black residents as they were fleeing the flames. “The number killed will never be known,” White wrote in The New Republic. “I asked a white citizen of Ocoee, who boasted of his participation in the slaughter, how many Negroes died. He declared that 56 people were known to have been killed—and he said he’d killed 17 ‘n——s’ himself.”

That man was almost certainly exaggerating. But even now, nobody knows how many people died in the riot because nearly every surviving Black resident, possibly including Moses Norman, quickly fled Ocoee. “At the time I visited Ocoee, the last colored family of Ocoee was leaving with their goods piled high on a motor truck with six colored children on top,” White wrote in an affidavit prepared for Florida officials. “White children stood around and jeered the Negroes who were leaving, threatened them with burning if they did not hurry up and get away. These children thought it a huge joke that some Negroes had been burned alive.”

Walter White didn’t visit the scene of every lynching in America in the 1920s—more than 300 people were lynched during that decade—but he investigated dozens, including the bloodiest.

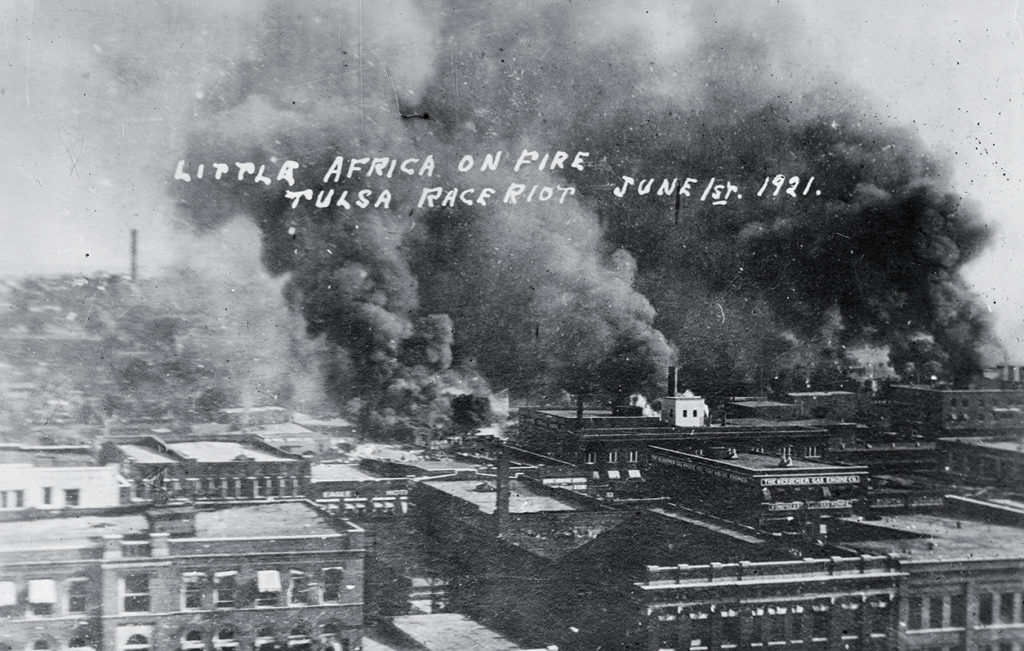

In June 1921, he traveled to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where rumors that a Black messenger boy had assaulted a White woman led mobs to burn more than 1,000 buildings in Greenwood, Tulsa’s Black neighborhood, killing between 100 and 300 people (“What Was Lost,” December 2021). White arrived two days later and soon had managed to enroll in an otherwise all-White posse. “Now you can go out and shoot any n—— you see,” a fellow posse member gleefully informed him, “and the law’ll be behind you.”

White’s accounts of lynchings ran in the New York Post, the Chicago Daily News, The Nation, and The New Republic. He also testified before congressional committees. But his favorite venue for telling his stories was in appearances before Black audiences across America. In those presentations, White did not ignore the inescapable horrors of his subject, but he preferred to emphasize the comedy of his role when conducting an investigation: He was a small, bespectacled Black man who posed as White and repeatedly bamboozled racist rubes into revealing their foul deeds.

“Black men and women filled the halls and lodges and churches where he appeared, laughing along with his tales of fooling the white man on their behalf,” Thomas Dyja wrote in his 2008 biography of White. “With these stories, White created a character, a skinny young black trickster who walked into the teeth of danger in the name of justice and who came out not only alive but laughing.”

Unfortunately, no recording or transcript of any of those speeches exists. But “I Investigate Lynchings,” an essay White wrote for H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury magazine in 1929, provides a hint of his comic style.

“Nothing contributes so much to the continued life of an investigator of lynchings, and his tranquil possession of all his limbs, as the obtuseness of the lynchers themselves,” White wrote. “Like most boastful people who practice direct action when it involves no personal risk, they just can’t help but talk about their deeds to any person who manifests even the slightest interest in them…They gabble on ad infinitum, apparently unable to keep from talking.”

“With his high-pitched voice, love of a joke and relentless energy, his speeches were entertainment of a high order,” Dyja wrote. “When the audience left, they told their neighbors the stories they’d heard from this character Walter White, who tricked out lynchers for the NAACP.”

White didn’t spend all his days nvestigating lynchings. He continued working in the NAACP office, attending to paperwork, dealing with local chapters, organizing conferences. In 1922, he married Gladys Powell, an NAACP stenographer, and soon fathered two children. He wrote two novels of Black life—Fire in the Flint and Flight—and participated in the artistic movement known as the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1927, White received a $2,500 Guggenheim fellowship to spend a year abroad while writing another novel. He moved his family to the French Riviera, but he didn’t write the novel. Instead, he wrote what he described as “a study of the complex influences—economic, political, social, religious, sexual—behind the gruesome phenomenon of lynching.”

He titled the book Rope and Faggot. Citing his own work and statistics gathered by scholars, White disputed the notion that most lynchings were responses to claims that Black men had raped or propositioned White women. Such alleged incidents accounted for less than 30 percent of lynchings and, White argued, most interracial sex was consensual. Far more often, a lynching’s cause was economic—to keep Black farmworkers subjugated or to punish prosperous African Americans. And most mob killings occurred in small, backward, rural towns where, White noted sarcastically, “lynching often takes the place of the merry-go–round, the theatre, the symphony orchestra and other diversions common to large communities.”

Published in 1929, Rope and Faggot received excellent press. Time magazine praised White’s book as an “arresting exposition of a not-yet-vanished U.S. folkway.” That review inspired a reader in Atlanta to write in a letter to the editor, “Down here we don’t care if all the Negroes are lynched, or even burned or slit open with knives.”

In 1929, White became the head of the NAACP. He led the group for 25 years. During his tenure as executive director, the organization achieved its greatest triumph when in 1954 NAACP lawyers, led by Thurgood Marshall, convinced the U.S. Supreme Court to declare segregation in public schools unconstitutional (“Becoming Jane Crow,” February 2022).

A year later, when White, 61, died of a heart attack, The New York Times called him “the nearest approach to a national leader of American Negroes since Booker T. Washington.” More than 1,800 people packed his Harlem funeral and thousands more lined the streets to watch a hearse carry the man known as “Mr. NAACP” to his grave.

Today, if you ask the average American, Black or White, “Who was Walter White?,” you’re liable to get a blank stare, though fans of long-form TV might perk up and say, “Walter White was the chemistry teacher turned meth dealer played by Bryan Cranston in Breaking Bad.” But the real Walter White—who repeatedly risked his life to expose the horrors of lynching—is, as biographer Thomas Dyja lamented, “all but forgotten.”