The Spartan-like defense and tragedy of Xuan Loc, April 1975.

The last major battle of the Vietnam War was fought at Xuan Loc, only 37 miles east by northeast of Saigon. In April 1975 the town was the eastern anchor of South Vietnam’s final line of defense against the North Vietnamese rush to the capital. That line ran west through Bien Hoa, just north of Saigon, to Tay Ninh, near the Cambodian border. Once it broke, Saigon was doomed—and with it the Republic of Vietnam itself.

When the North Vietnamese Army attacked Xuan Loc (pronounced Swan Lock) on April 9, the communists and almost everyone else expected the Army of the Republic of Vietnam’s 18th Division to collapse like a house of cards, as had so many other ARVN units during the NVA’s massive Spring Offensive of 1975. But ARVN forces under Brig. Gen. Le Minh Dao fought fiercely in a last-ditch effort to save their country. By the time Xuan Loc did fall 12 days later, most of the world was amazed at how well the ARVN had fought, and the NVA had paid a far steeper price than it expected. Indeed, the valiant stand at Xuan Loc by heavily outnumbered ARVN soldiers echoes the famed sacrifice of King Leonidas’ 300 Spartans facing Xerxes’ Persian masses at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. Greece. The Persians then marched south and captured Athens.

Xuan Loc, the capital of Long Khanh province, had always been a strategically sensitive place. The town sat astride the French-built Highway 1, near the junction with Highway 20. From Xuan Loc, Highway 1 ran almost 40 miles east until it reached the South China Sea, where it turned north and went up the coast past the Demilitarized Zone and on to Hanoi.

From March 1967 to January 1969 the U.S. 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment’s Blackhorse Base Camp was some 4 miles south of Xuan Loc. During that time, Highway 1 was relatively secure from Xuan Loc west toward the northern edge of Saigon. But since 1962 the road east to the coast had been shut down completely, as it ran through the heart of the May Tao “Secret Zone,” a mountainous area where the Viet Cong 5th Division was based and U.S. intelligence hadn’t penetrated. From November 1967 to early 1968, Operation Santa Fe, conducted by the U.S. 9th Infantry Division’s 1st Brigade, the 1st Australian Task Force and the ARVN 18th Division, attempted to open Highway 1 to the coast. Although the road was eventually opened, the VC 5th Division mostly avoided contact as it positioned itself for the Tet Offensive in late January 1968.

During the war, North Vietnam launched three major offensives against South Vietnam. The Tet Offensive of 1968 and the Easter Offensive of 1972 were military failures. The 1975 Spring Offensive would succeed. By that time, all U.S. forces were out of Vietnam, and legislation passed by Congress in June 1973 prohibited the use of government funds for military operations in Southeast Asia without congressional approval.

In 1975 North Vietnam, which had organized its army divisions into four corps, committed all four to attacks on the South. The NVA force in South Vietnam totaled 270,000 troops, 1,076 artillery pieces and mortars, 320 tanks and 250 other armored vehicles.

After successful probes in early 1975 in the northern sector of the South Vietnamese III Corps Tactical Zone (a military region encompassing Saigon and provinces to the north), the NVA on March 8 launched Campaign 275, directed at Ban Me Thuot, a provincial capital in the Central Highlands, part of the II Corps zone. The ARVN held out for eight days. When Ban Me Thuot fell, Pleiku and Kontum, also in the Central Highlands, were outflanked and cut off from the south. NVA forces quickly drove toward An Khe and the coast—effectively cutting South Vietnam in two. The NVA then took the northern I Corps zone cities of Hue and Da Nang, which fell on March 29.

ARVN units in those areas had quickly collapsed during the relentless NVA advance. They abandoned their positions and joined tens of thousands of panic-stricken refugees trying to escape to the south, bringing widespread looting and destruction in their wake. By the end of March, the NVA effectively controlled the entire northern half of South Vietnam.

Ignoring frantic pleading from South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, the United States would not intervene, despite security guarantees given to Saigon in the January 1973 Paris Peace Accords. Even if the president wanted to provide military support, the War Powers Act, enacted in November 1973, severely restricted his ability to commit U.S. forces on his own.

The NVA, meanwhile, positioned its forces for the Ho Chi Minh Campaign, the final phase of the conquest of South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese IV Corps advanced on Xuan Loc from the northeast, while the NVA II Corps converged on the town from the northwest. The ARVN 18th Infantry Division was essentially all that stood in their way.

Earlier in the war, the 18th Infantry Division had the reputation as one of the ARVN’s worst units. That changed rapidly in March 1972, after 39-year-old Dao assumed command. Dynamic and aggressive, he was one of the best officers in the ARVN. Unlike so many other ARVN senior officers, whose careers had been built on family, social and political connections—even on bribery and corruption—Dao advanced on sheer ability. Despite the youthful good looks and large dark sunglasses that gave the impression he was just another playboy from the elite, privileged class of South Vietnamese, Dao had an inner core of steel and one of the finest tactical minds on either side of the Vietnam War.

The general eschewed a palatial villa in favor of a modest two-story house close to where his troops were billeted. During the battle, Dao spent much of his time moving among his frontline troops rather than issuing orders from a secure command post bunker. He insisted that all his officers maintain close contact with subordinates at least “two levels down.” It was an unorthodox style of leadership in an army characterized by a rigid class stratification between officers and enlisted men. Dao’s troops repaid their commander with unstinting devotion and loyalty.

Before the fight at Xuan Loc, Dao defiantly told foreign journalists: “I am determined to hold Xuan Loc. I don’t care how many divisions the communist will send against me. I will smash them all! The world shall see the strength and skill of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.”

Dao and his commanders prepared well. First, they evacuated the soldiers’ families to the relative safety of the huge logistical base at Long Binh, close to Saigon, enabling the men to focus on the fight because their families were out of immediate harm’s way. Dao also had the foresight to establish two fully functional alternate divisional command posts.

After studying the approach routes the communists had used to attack Xuan Loc during the 1968 Tet Offensive, Dao moved his 36 divisional field artillery pieces to positions where they could mass their fire into a triangular kill zone on the western side of the town. He placed his guns in reinforced revetments, stockpiled with ammunition, and had them adjusted for pinpoint accuracy on enemy artillery positions and all potential routes of attack. He sent infantry patrols to occupy key pieces of high ground the NVA could use as artillery observation posts.

One of the most important pieces of high ground was Nui Soc Lu, known as Ghost Mountain, astride Highway 20 and just outside the northwestern edge of Xuan Loc’s defensive perimeter.

Dao positioned two long-range 175 mm M107 self-propelled guns at Tan Phong, his first alternate command post, near the southern edge of Xaun Loc’s defensive perimeter. He had his communications and intelligence troops monitor all known NVA radio frequencies, and he studied the intercept reports daily.

In addition to the 18th Division’s own 43rd, 48th and 52nd Infantry regiments and the 181st and 182nd Field Artillery battalions, Dao’s attached forces included troops from South Vietnamese militia organizations—four Regional Force battalions and two Popular Force companies.

The NVA’s IV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Do Van Cam, whose nom de guerre was Hoang Cam, moved toward Xuan Loc with its 6th, 7th and 341st Infantry divisions, supported by two armored and two artillery battalions, an anti-aircraft artillery regiment, two combat engineering regiments and a signals regiment. Cam’s forward command post was at Nui Chua Chan mountain, outside the eastern end of the Xuan Loc defensive perimeter. The NVA attackers numbered some 20,000, the ARVN defenders about 12,000.

To disrupt the NVA deployment, Dao sent a battalion-sized blocking force from the 52nd Infantry Regiment north along Highway 20 on March 28. For two days those troops held off the NVA 341st Division. By April 1, however, the South Vietnamese soldiers were pushed back to the Xuan Loc perimeter. They brought with them several prisoners of war, and interrogations revealed that many of the 341st Division POWs were barely 16 years old and largely untrained, although all were carrying modern Soviet bloc weapons.

The battle for Xuan Loc started at 5:40 a.m. on April 9 with an intense artillery barrage. The NVA gunners’ well-targeted very first shell hit Dao’s house and exploded in the bedroom. It was followed by 2,000 more rounds. At 6:40 a.m. the barrage ended, and NVA tanks and infantry moved against the town from three directions. When the shooting started, Dao was in Long Binh, where he had gone the previous day to coordinate logistical support for his division. Alerted to the attack in a phone call from his chief of staff, Dao left by helicopter for Xuan Loc. En route, he received situation reports by radio from regimental commanders.

The communists were certain Dao’s troops would break and run as soon as the artillery barrage lifted, but the ARVN soldiers held their ground. The NVA’s 7th Division carried out the main assault, attacking from the northeast without tank support. It was slowed by eight belts of barbed wire and minefields, then pummeled from the air by the South Vietnamese air force A-37B Dragonfly attack planes and F-5E Tiger fighters.

Later that morning the North Vietnamese reinforced the 7th Division with eight T-54 tanks. ARVN soldiers destroyed three of them but lost seven of their own M41 Walker Bulldog tanks. The attack from the northeast finally stalled, but not before the 7th Division overran Dao’s main command post. The general, however, had already shifted his divisional headquarters to the alternate command post at Tan Phong.

The NVA 341st Division, attacking from the northwest, entered Xuan Loc and captured an ARVN communications center, along with a local police station. But the untrained North Vietnamese teenagers could not exploit their initial gains. They were driven back by the ARVN 52nd Regimental Task Force, supported by a South Vietnamese C-119 gunship.

The 6th Division made the only significant NVA gains. Attacking from the south, its troops interdicted Highway 1 east of the Dau Giay intersection with Highway 20, cutting off Xuan Loc from Saigon. When the battle’s first day ended, the NVA had suffered about 700 dead and wounded, the ARVN 18th Division fewer than 50.

The battle seesawed back and forth for the next two days. At 5:27 a.m. on April 10, NVA artillery opened up with a 1,000-round barrage. The NVA 7th and 341st divisions attacked in their respective sectors but were driven back repeatedly by ARVN counterattacks, sometimes in hand-to-hand fighting. The communists lost five more tanks. Dao ordered two battalions to attack two 341st Division regiments that had reached the heart of the town, and many of the teenage NVA troops broke in panic, scattering into Xuan Loc’s sewers and ruined cellars. Some captured later had not fired a single bullet from their 72-round basic load.

Meanwhile, fighter-bombers in South Vietnam’s 3rd and 5th Air divisions, operating from the Bien Hoa and Tan Son Nhut air bases on the outskirts of Saigon, flew more than 200 sorties in support of the besieged garrison. That night, North Vietnamese artillery fired 2,000 rounds into Xuan Loc, but Dao’s gunners kept up an effective counterbattery fire.

Early in the morning of April 11, NVA artillery opened fire with a 30-minute barrage. The 7th and 341st divisions then resumed their attacks, but again without success. IV Corps commander Cam, who had led a battalion of Viet Minh independence fighters against the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, later wrote: “This was the most ferocious battle I had ever been involved in! My personal assessment was that, after three days of battle, even after committing our reserves, the situation had not improved and we had suffered significant casualties.”

Cam estimated that during the battle’s first three days his 7th Division had suffered 300 casualties, and the green teens of the 341st Division 1,200. Virtually all of the NVA’s 85 mm and 75 mm artillery pieces had been knocked out by ARVN counterfire.

Despite Dao’s strong defense of Xuan Loc thus far, the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff knew it had to reinforce him. The 11th Armored Brigade was committed from the west on April 11 to clear Highway 1 to the Dau Giay intersection, but the brigade’s 322nd Armored Regiment lost 11 tanks and could not dislodge the NVA.

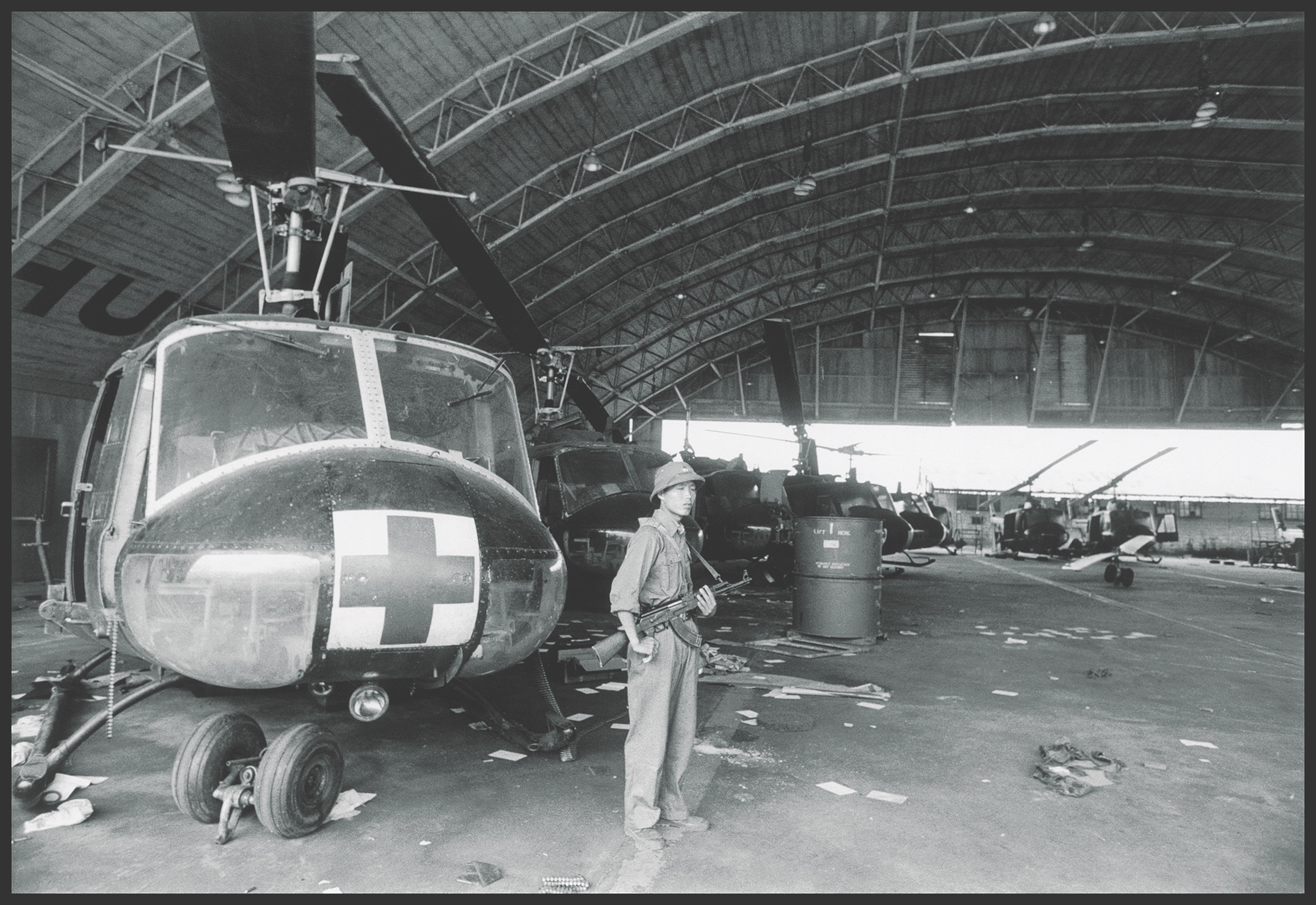

The 1st Airborne Brigade, taking off from Bien Hoa in 100 UH-1B Huey helicopters on April 12, landed near the Bao Dinh rubber tree plantation south of Xuan Loc. CH-47 Chinook transport helicopters brought in the brigade’s supporting artillery and 93 tons of ammunition. On their return to the base, the choppers evacuated wounded 18th Division troops and local civilians in the last large-scale helicopter operation of the war.

Two marine battalions were ordered to form blocking positions between Xuan Loc and Bien Hoa, while ranger, infantry and artillery battalions provided reinforcements against an NVA attack toward Dau Giay. Meanwhile, the air force continued to pound the NVA, dropping several huge 15,000-pound BLU-82 “Daisy Cutter” bombs from C-130 Hercules cargo planes.

By the end of the fourth day, NVA dead totaled close to 2,000. Col. Gen. Tran Van Tra, the NVA officer who commanded the Viet Cong and the southern region, assumed personal control of the battle on April 13, and IV Corps was reinforced with additional troops, tanks and artillery. That same day, Dao was hit in the arm by artillery shell fragmentation. Tra shifted the NVA’s main thrust away from the center of Xuan Loc. He ordered the 6th and 341st Infantry divisions to concentrate instead on hitting Dau Giay, the linchpin of Xuan’s Loc’s defenses, from the north and the south, while establishing blocking positions to the west along Highway 1.

In Saigon, Thieu declared that Dao’s successful defense of Xuan Loc had ended the long string of communist successes and the ARVN had “recovered its fighting ability.” He spoke too soon. The NVA reinforcements included the 95B Infantry Regiment, one of North Vietnam’s elite units, which had been in the Central Highlands.

Tra quickly recognized the mistake of the original attack strategy: The NVA had not been interdicting South Vietnamese aircraft taking off from Bien Hoa. Communist gunners shifted their targets from Xuan Loc and began shelling the air base with heavy rocket and artillery fire on April 15. Almost immediately the 3rd Air Division at Bien Hoa was forced to suspend flight operations. NVA commandos infiltrated the base and blew up part of the ammo dump.

The South Vietnamese tried to shift air support operations to the 4th Air Division, flying out of Binh Thuy Air Base in the Mekong Delta, a switch that in the end didn’t matter. That same day, the NVA 6th Infantry Division and 95B Infantry Regiment captured Dau Giay. During the next two days the 6th Division beat back all ARVN attempts to retake Dau Giay. Simultaneously, the 7th and 341st Infantry divisions relentlessly hammered the defenders all around Xuan Loc, inflicting especially heavy losses on the 1st Airborne Brigade.

Xuan Loc was now cut off from reinforcement by land. Air support from Bien Hoa was drastically reduced. And the North Vietnamese II Corps was moving down from the northwest. The capture of the town was inevitable. Yet, the fierce and skillful ARVN resistance had shaken the NVA and disrupted the schedule for a final assault on Saigon. Hanoi postponed a planned April 15 attack to allow more forces to converge from the north and finally overrun Xuan Loc.

On April 17 the Senate Armed Services Committee rejected President Gerald Ford’s request for $722 million in emergency support for Saigon. On April 20, South Vietnam’s Joint General Staff ordered Dao to evacuate Xuan Loc and withdraw to Bien Hoa to establish a new center of resistance.

The withdrawal began that night under cover of heavy rainfall. In a skillfully coordinated maneuver, Dao’s troops pulled out by echelon, south through the rubber plantations, along the dirt-road Route 2. The 1st Airborne Brigade acted as the rear guard. NVA troops, taken by surprise, could do little to disrupt the withdrawal.

Unlike so many other ARVN generals who had flown out by helicopter during the 1975 communist offensive, Dao marched out on foot with his troops. In the early morning hours of April 21, the NVA scored its only success against the withdrawal when it destroyed the rearguard 3rd Battalion, 1st Airborne Brigade, near Suoi Ca hamlet. Later that day Hanoi’s troops moved into the deserted Xuan Loc, then little more than a pile of rubble.

In Saigon, Thieu resigned as president and was replaced by Tran Van Huong. The air force, however, still had one final blow to strike. On April 22 a C-130 dropped a 750-pound CBU-55 fuel-air bomb, approaching the explosive power of a nuclear bomb, on the headquarters of the 341st Division. The bomb sucked the oxygen out of the air and killed an estimated 250 NVA soldiers in the only time a CBU-55 was used in Vietnam.

South Vietnam’s 18th Division had suffered 30 percent casualties in defense of Xuan Loc. Its attached Regional Force and Popular Force units were virtually wiped out. The division spent three days at Bien Hoa preparing for the final defense of Saigon. On April 23 Huong promoted Dao to major general. The 18th Division was in defensive positions near the National Military Cemetery close to Bien Hoa when Saigon surrendered on April 30.

Dao wanted to keep on fighting. Dressed in civilian clothes, he made his way south into the Delta, trying to reach Can Tho, the ARVN headquarters for the IV Corps Tactical Zone. Before he got there, however, the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Nguyen Khoa Nam, and his deputy, Gen. Le Van Hung, committed suicide. Dao surrendered on May 9 and spent the next 17 years in brutally repressive “re-education camps.” In May 1992 he was one of the last four senior ARVN officers freed. Dao arrived in the United States in April 1993.

Throughout the war Americans asked themselves how the North Vietnamese could fight so well and the South Vietnamese could not. The Battle of Xuan Loc indisputably proved the ARVN could fight. The key was leadership. The ARVN’s great weakness was that it never had enough generals like Dao, who at Xuan Loc went head-to-head with far more experienced NVA generals, Do Van Cam and Tran Van Tra. Le Minh Dao was the Leonidas at South Vietnam’s Thermopylae.

Retired Army Maj. Gen. David T. Zabecki is editor emeritus of Vietnam magazine.

This feature originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. To subscribe, click here.