The critical and financial success of his 2010 book Empire of the Summer Moon, a New York Times bestseller and Pulitzer Prize finalist, allowed S.C. (Sam) Gwynne a long-awaited, golden opportunity to expand his literary horizons and to take a few risks with any subsequent endeavors. A transplanted Yankee now living in Austin, where he worked as executive editor at Texas Monthly magazine, Gwynne began searching for a Civil War topic he could explore, finally deciding to take on Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Gwynne had been intrigued by the Civil War since he was a young adult but had not yet written to any extent about America’s seminal struggle. Not only was Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson, published in 2014, another bestseller for Gwynne—and a finalist for both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the PEN Literary Award for Biography—it gave him a new appreciation of the Civil War and of one of its most luminous yet controversial commanders.

In 2016, Gwynne penned a book about another of his favorite topics, football, but in 2019 he returned to the war for the critically acclaimed Hymns of the Republic: The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War, which was released in a paperback edition in October. Gwynne, 67, talked to America’s Civil War during a Zoom Q&A session at the annual Boerne (Texas) Book & Arts Festival on October 4, 2020

By S.C. Gwynne

Scribner, 2019, $32

Tell us about the title of your book, Hymns of the Republic?

It’s a play on “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” At some point in my research, I became aware of something that was known as the “Black Battle Hymn of the Republic.” It was sung by slaves and Black Americans. The idea just suggested to me that there were other hymns, that there were hymns of different constituencies and people. What I mean by that is by looking at this last year of the war, which is what the book is about, it was meant to be a look at different pieces of that war and not, say, simply the Union Army.

This is your second book on the Civil War—you earlier authored an account of Stonewall Jackson. How did you get interested in the subject?

Two simple words: Bruce and Catton. Bruce Catton was one of the main popularizers of the Civil War. He was the guy who made everybody say, “We just love reading about the Civil War.” He had best sellers like Mr. Lincoln’s War and A Stillness at Appomattox. I guess I was in early adulthood when I first read Catton. So many books about the Civil War are the bullet-by-bullet account of what went on: What the 23rd North Carolina was doing at 9:43 a.m., extremely detailed battle stuff like that. Which is fine, and I sort of like to read that stuff, but it’s not as entertaining, it’s not a great narrative. Catton wrote great narratives.

I always found the Civil War the most compelling thing in American history; to me nothing is even a close second to it. It is definitive of our nation, dramatic and complex beyond your wildest dreams, just a wonderful thing to write about. I was lucky enough with Empire of the Summer Moon to have a bestseller. Most writers are not lucky enough to have that and there are plenty of really good books that don’t sell well. I got lucky, and when you get lucky like that, a window opens, if however briefly. At some point, I thought if I could just do anything I wanted to do, what would that be? I came very quickly to two names: Ulysses S. Grant and Stonewall Jackson. And I thought Grant had been a little overdone. It seems as though every year there are 20 books on Grant.

Regarding your narrative style in this new book. As a recent review noted: “In the aftermath of the war, Herman Melville published Battle Pieces and Aspects of War. Years later, Walt Whitman released Specimen Days. For many writers, it seemed that the best way to tell the war’s story was through specific moments and lives. S.C. Gwynne, in his miracle and masterful Hymns of the Republic, follows in that tradition.” You’re being compared here to Melville and Whitman in your approach. Was that deliberate?

There’s no shortage of stuff out there, so the idea at some level is to try to cut through and make fresh observations, to try to step back from that awesome burden of looking at the battles up close. Now, I did some of that in my Stonewall Jackson book. The reason is because he was possibly the most brilliant military commander in history and you have to look at the battles—you have look at his [1862 Shenandoah] Valley Campaign—and follow it closely, because otherwise how can you establish his genius?

But in Hymns I wanted to step back a little bit and write a less data-heavy narrative. We have a wonderful writer here in Austin, Lawrence Wright. Larry has a great explanation of how he structures his narratives. He says the first thing you’ve got to find is a “donkey.” The donkey is the character who is interesting and engaged enough to carry the narrative. In “Rebel Yell,” I had one main “donkey,” Jackson himself. In Hymns, because I’m sweeping through an entire year in Hymns, there are going to be different donkeys. Young Robert E. Lee at one point is. Clara Barton at one point is. This great Black journalist from Philadelphia, Thomas Morris Chester, is another one. Salmon P. Chase another. John Singleton Mosby. The weird genius/incompetent Ben Butler. And so on. These guys carry that narrative along in a way that I hope helps the reader make sense of what’s going on.

Your opening chapter sets up the book nicely. Various characters are introduced, from the “Angel of the Battlefield” Clara Barton, to the Black soldiers, to the great Confederate strategists who bedeviled the North, to the incompetent Union generals. At first these feel like individual portraits, but then they start meshing to collaboratively tell the story of that final year. We feel like we are on the front row of history. You take us into Washington, D.C., in March 1864. You describe what the capital is like at that time. You describe the arrival of Ulysses Grant.

I set it up by talking about the social whirl that’s going on inside Washington in Spring 1864, the presidential receptions and levees and all these huge parties. There is finally some hope for the North in the war. This hope is about to be dashed, but for the moment everyone is obsessed with the arrival in Washington of Ulysses S. Grant, the great victor of the West.

The leading Union generals in the first part of the war were a disaster, one incompetent after another—George McClellan probably being the most famous—who gave away the Northern advantages of troops and men and material and everything else. Grant was different. And yet here was this other guy. He had won at Forts Henry and Donelson, at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. He fought hard and didn’t back off and didn’t lose. So, finally he’s arriving. That’s the moment I choose.

It’s a great story because it tells you how different the world was. Grant arrives at Union Station with his son Fred, who was 13, and his assistant—that’s it. No glorious entourage, as McClellan had once had. Grant is coming to Washington to accept a commission that only two generals before, George Washington and Winfield Scott, had ever been given: lieutenant general. Grant gets off the train and is standing in Union looking around, but because of a logistical error no one has come to meet him. So, he takes a cab to the War Department, where his boss Henry Halleck is. But Halleck’s not there, so then he takes another cab to Halleck’s home, Halleck’s not there either. So, having tried three times now to find somebody who would welcome him, Grant goes to the Willard Hotel. He walks in unrecognized, and one of the reasons he’s unrecognized is because, other than his four years at West Point, he has never spent much time in the East.

Nobody knows what he looks like, which is interesting because Grant by this point is as famous as Lincoln and much more popular. He’s had millions of words and ink expended on him. He’s got a full length painting of him hanging over in Congress. But he walks into the Willard unrecognized. He and Fred go upstairs. When they come down for dinner, he seats himself unrecognized. Now remember the level of fame we’re talking about here; it’s as if Barack Obama and Lady Gaga walked through the lobby of the Willard unrecognized.

Eventually the people in the dining room begin to realize who he is and eventually the place goes completely crazy, but nowhere near as crazy as the White House does an hour later when he shows up at a reception for Lincoln. The scene quickly turns into a sort of genteel riot, with ladies trying to touch him, and dresses being torn, and at one point William Seward, the secretary of state, has to take Grant up onto a sofa to avoid being crushed by the crowd.

The reason for all this is because Grant was coming to save the Union. Nothing less. That is what people in the North thought. The Confederates’ indomitable genius of the East [Lee] was going to meet the great Union genius of the West in single combat, if you will, in Northern Virginia. The fighting was going to be definitive and the war was going to be over. People on both sides believed that.

My opening chapter tries to capture this moment when the future of the war and that nation—and specifically the fate of Abraham Lincoln, seemed to hang in the balance. Everything was indeed in the balance.

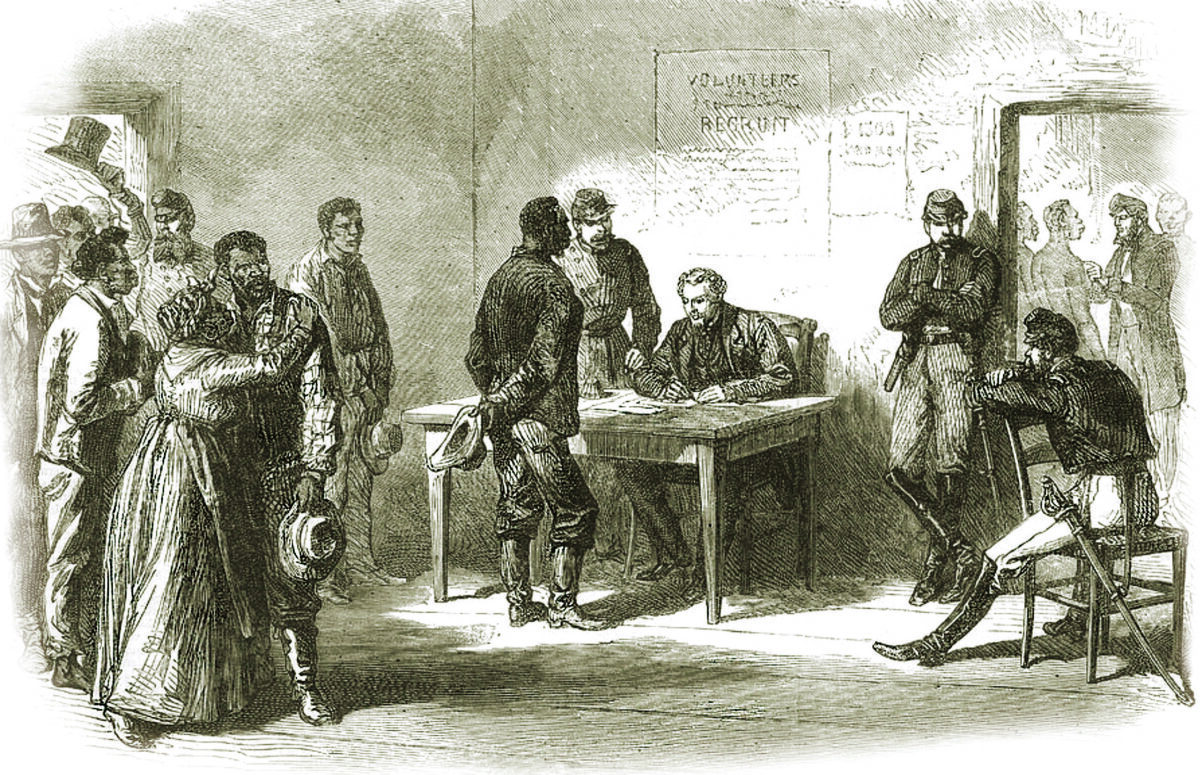

It is fascinating to read about the African American soldiers fighting for the North and the belated attempt by the Confederacy to perhaps recruit some slaves to fight for them. Tell us more about that.

I spend a lot of time on Black soldiers in the book. The big picture is that 180,000 Black soldiers fought in the Union Army, mostly in the final year of the war. That’s 10 percent of the army, which still kind of shocks me. I knew a few things about the Civil War growing up, but I knew nothing about that side of it. When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863, he included a paragraph that changed American history: Black soldiers could be combatants in the war. And not only that, but it was going to be encouraged. In Lincoln’s mind, the driver of real emancipation was going to be enlistment. Enlistment was going to be the way it was going to happen, not only for escaped slaves but for all African American men in the North. Suddenly someone crosses through a Union army line and comes out on the other side a man with a uniform and a salary.

Now, these African American soldiers were not treated very well. They were second class citizens in the army, treated and paid as such. But the fact was, as Frederick Douglass said, you put a gun in his hand, you give him money, you put a uniform on him, he’s fighting for the United States, he’s no longer a no-account slave—he is a soldier and citizen. In the last year of the war, this is when it really comes to bear, this enormous weight of Black soldiers. And, remember, it was not easy for these guys, they were not treated well by Northern officers. They weren’t paid fairly, they were abused—in some cases they were treated like slaves by those officers.

They acquitted themselves so well time and time again. The story you tell about the African American soldiers being the first ones into Richmond when the Confederate capital falls is a great story.

It’s April 1865. Richmond has fallen, it’s burning—everybody in the government has fled. As the Union soldiers approach, they’re expecting to see what they usually see, which is trenches bristling with guns. But they realize there’s no one there and just walk right through these enormous defensive positions, now empty. The first ones through are the black 25th Corps. They end up stopping about three miles east of the capital, at which point the mayor of Richmond officially surrenders, and the slaves come out and they can’t believe their eyes. They didn’t even know there was such a thing as a Black soldier. From there a single road leads into Capital Square, the center of Richmond. And it’s very clear, and they all understand that the first infantry into the fallen, burning capital of the South is going to be doing something that will go down in history. The men who did it would be telling stories about it to their great grandchildren. Everybody knew what that meant.

At this point, the all-White 24th Corps of the Union Army of the James shows up, and now a decision has to be made. Who is going first? And, of course, that’s a no brainer, in the context of the Union Army in 1865. The White guys are going first. And so the men of the 24th take off down the road, visions of glory in their eyes. But the Black soldiers just won’t accept this. So they take off through field and farm and over stone walls and fences, and they’re so motivated that they get into the city core before the White soldiers do.

Now the White soldiers are very upset about this, and in fact a campaign was started right at that moment to discredit the Black soldiers and to revise the history so that it was the White soldiers who got there first. But history has favored the Black soldiers. One of the reasons for that is that a Black correspondent for a Philadelphia newspaper, Thomas Morris Chester, happened to be there. He was the only Black correspondent at a major Northern newspaper—the Philadelphia Press—and he had positioned himself so he could see who the first soldiers were. He then wrote about it. In order to write his story, he repairs to the Confederate House of Representatives, where he is seated in the House Speaker’s chair when a Confederate officer who had been paroled approaches him and tells him to leave. Chester looked up, said nothing, and continued writing. The Confederate officer charged him, whereupon Chester, who was a pretty big guy, stood up and decked him. Now furious, the Rebel officer turns to a nearby Union officer and says, something to the effect of, give me your sword so that I may thrash this man. The Union soldier declines but offers to clear the floor of the House of Representatives so the two men could have a fight. The Confederate officer declines the invitation.

Later Chester explains why he had gone to sit in the chair, an action that might have been punishable by death the day before. When asked about it, he says, “Well, I thought about it and I thought I would exercise my rights as a belligerent.” That was one of my favorite stories, and there were so many of them in the war.

The controversy that has emerged over Confederate statues, what is your take on that?

It’s an interesting question. I mean, I’m a Yankee. And when I first came to Austin and saw that statue on the south lawn of the capitol—which basically was a statue of the Confederacy saying, “These boys died for states’ rights” and the old “Lost Cause” BS about how the war wasn’t about slavery—I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe there was a statue like that on the lawn of the capitol. Of course, I was a naïve Yankee and didn’t yet understand.

I’ve come to the conclusion that you cannot defend these statues. I came to it reluctantly initially because the historian in me opposed the idea of expunging people and events from history so that no one would ever know what had happened. Therefore, they have to either be sequestered somewhere or they have to be taken down. I had a really interesting conversation last summer with Stonewall Jackson’s great-grandson, who wrote a column in the Richmond paper advocating that the Jackson statue there be taken down. I mean, even Jackson’s heirs want that to happen.

But I also have a Yankee perspective on it, and it’s a very slippery slope. If our standard is everyone who owned slaves or fought for the South has to be erased from history or put in some dark and shameful corner, then you have a real problem on your hands. Fifteen U.S. presidents owned slaves, ten while they were in office. Ulysses S. Grant owned slaves; Abraham Lincoln’s wife was from a wealthy, slave-owning family. My native land, the seemingly pure and pristine and morally wonderful Connecticut and Massachusetts, was responsible for most of the American slave trade.

Newport, R.I., alone launched a thousand voyages to the Middle Passage, and the slave trade from the Middle Passage was way more heinous than what 98 percent of any Confederates ever did. Bolting people into 4-foot high decks for the passage across the ocean, this is what my people did. The biggest slave market in the country was in New York City. To pick out, say, Lafayette McLaws or some other Confederate general and say, “Well, that statue has to come down.” I’m not going to disagree with it, but there’s a certain sanctimoniousness, particularly among people who are from where I’m from, that alleges and somehow believes that we weren’t responsible.

The most brilliant speech ever given was Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. He said what no one at the time was saying, that slavery is a sin of which we are all guilty. Everybody was pointing fingers back then, right? North, South, you’re guilty, you’re to blame, you’re the slave owners. Lincoln says, “No, we are all guilty, this is something wound around the core of our nation’s history.” And that’s the way he interprets the Civil War. Essentially he’s interpreting it as blood atonement for the sin of slavery—the national sin of slavery.

I guess I advocate perspective when it comes to this. The question of how to treat slavery and history is never as clear or clean as you would like it to be. If you looked at Stonewall Jackson as a slaveowner, which he was, you can’t ignore that he was so much more enlightened than Thomas Jefferson. Three of Jackson’s slaves, as I write about in my book, he rescued; people begged him to buy them in order to save them. Another one he gave his freedom to and then when that man got sick, he financed his treatment and recovery, which hardly anyone did….Any way you might want to measure, he was an enlightened slave owner, certainly compared to a lot of U.S. presidents.

In light of everything that’s happened, do you feel differently about Stonewall Jackson? Are you still able to see him as this brilliant strategist, divorced from the ethical perspective that he had and so forth?

Do I feel differently about Jackson? No, Jackson is just one way of looking at the war and I tried to look at him objectively. In Hymns, I spent a lot of time looking at the war through the lens of Black soldiers, which I think is another valid way of doing so. Occasionally, I would run into an interviewer who expected me to devote pages and pages condemning Confederates in my Stonewall Jackson biography. But I was using him as a lens through which to look at history. I wasn’t making value judgments and saying, “Yeah, well he was not as bad as so and so, but worse than so and so.” I was trying not to do that.

In reading your book, it seems that the very success of Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee managed to prolong the war long past the point where the South should have kept fighting. It’s a consequence of their brilliance that the South suffered so terribly. Because of what was going on, that was such a great irony to consider.

I came up with a term for it: the Lee Paradox. The more Lee won, the more the South was destroyed. The more Lee won—or at least did not lose—the more he himself was destroyed. And at the end of the war, we’re talking about destruction on a scale of not just Sherman burning his way through Georgia and the Carolinas or Sheridan burning the Shenandoah Valley, but just the economic disaster that the war brought on the South—people starving to death, refugees on the road. The lengthening of the war also unleashed a guerrilla conflict on a scale previously unseen. And prison camps that had never existed before, these ungodly places like Andersonville [in Georgia] or Elmira in New York, a Yankee prison camp that was just as bad as Andersonville.

I’ll close with this: Lee’s greatest moment to me was after he and his army had been chased westward in Virginia out toward Appomattox. At this point all sorts of people are advocating that the Confederacy, what’s left of it, take to the hills and engage in interminable guerrilla war in Virginia that no one could stop. You could take to the hills and do that. Jefferson Davis, his remaining Cabinet members all advocated for that; a number of Lee’s trusted staff officers did so as well. Lee could have said, “We’re not going to surrender, just going to keep fighting.” And he didn’t. He used the full moral weight of his office and his personality to say, “No, we’re not going to do that.” It would have been just the worst thing in the world for the country if he hadn’t.