On Nov. 20, 1970, at 6 p.m., U.S. Special Forces Sgt. Terry Buckler reported to an auditorium at Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base. Hours earlier, he had been fed a sleeping pill and steak for lunch and told to get some sleep. Army Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons, deputy commander of the operation Buckler had been training for, entered with Lt. Col. Elliot Sydnor Jr., the operation’s ground force commander. Simons pulled out a map of North Vietnam. Hanoi was circled, with the town of Son Tay nearby.

Simons tapped Son Tay and said: “That’s where we’re going tonight, guys. We are going to rescue as many as 70 POWs. Americans have a right to expect this from their fellow soldiers. We have a 50-50 chance of not making it back. If you do not want to go, now is the time to say so.”

As Buckler remembers, “That auditorium got dead silence for about five seconds and then you thought a cannon got shot. These guys jumped out of their seats, hugging and yelling, ‘Let’s go get ’em!’” Soldiers who had trained as alternates for months were disappointed that no one dropped out.

Everyone, from President Richard Nixon to individual raiders, recognized the moral imperative of the mission and the need to live up to the U.S. military’s ethos to “leave no man behind.” They also realized that when the rescued prisoners of war revealed the brutal treatment they had received in captivity it could help turn world opinion against the North Vietnamese and force them back to the stalled Paris peace talks.

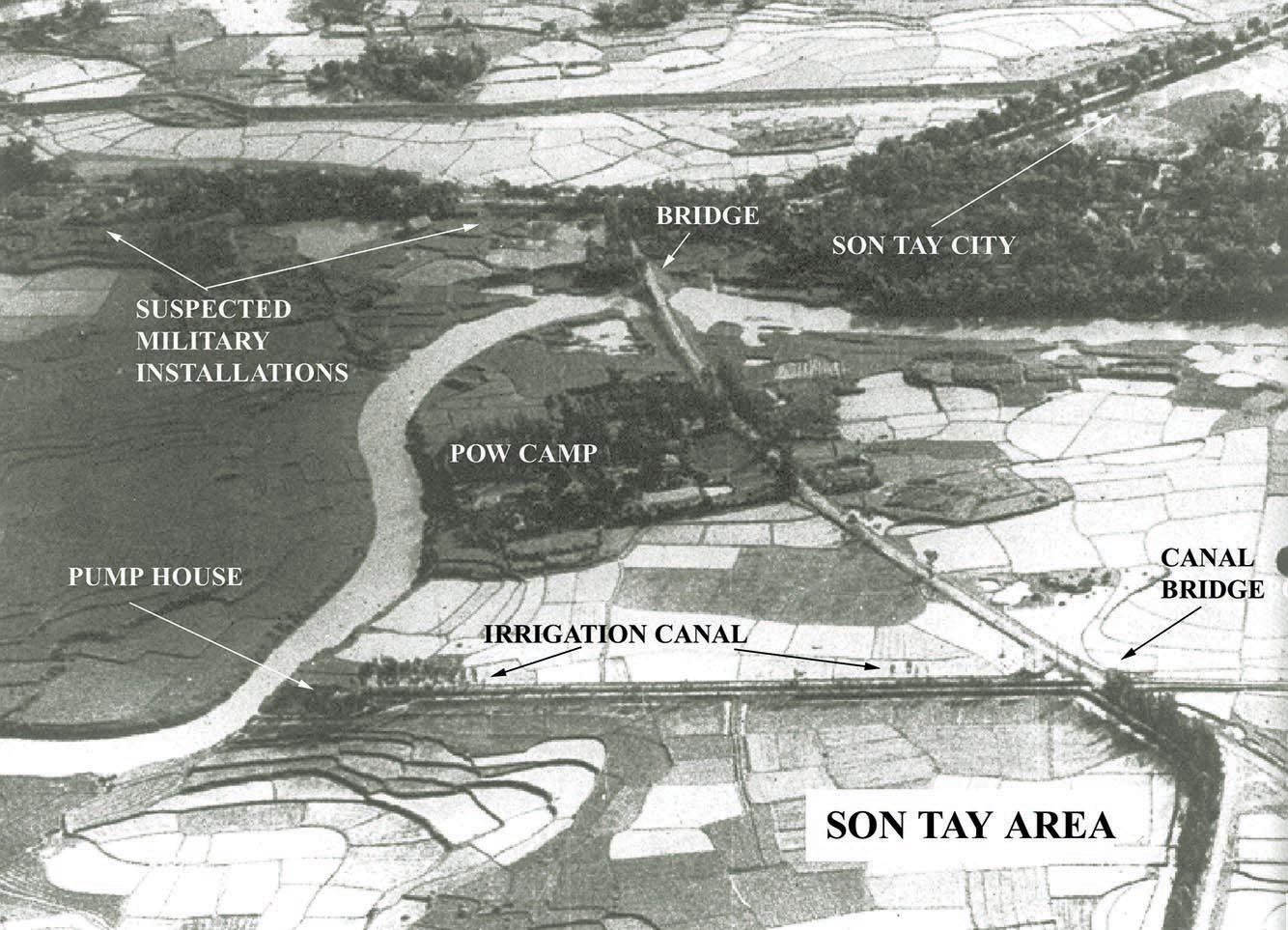

In May 1970, intelligence analysts in a unit keeping tabs on POWs noticed photos of new construction at a compound in Son Tay, along with POW uniforms laid out to dry on the ground in a manner spelling a code for search and rescue. A dirt pile resembled a “K,” meaning “Come get us.”

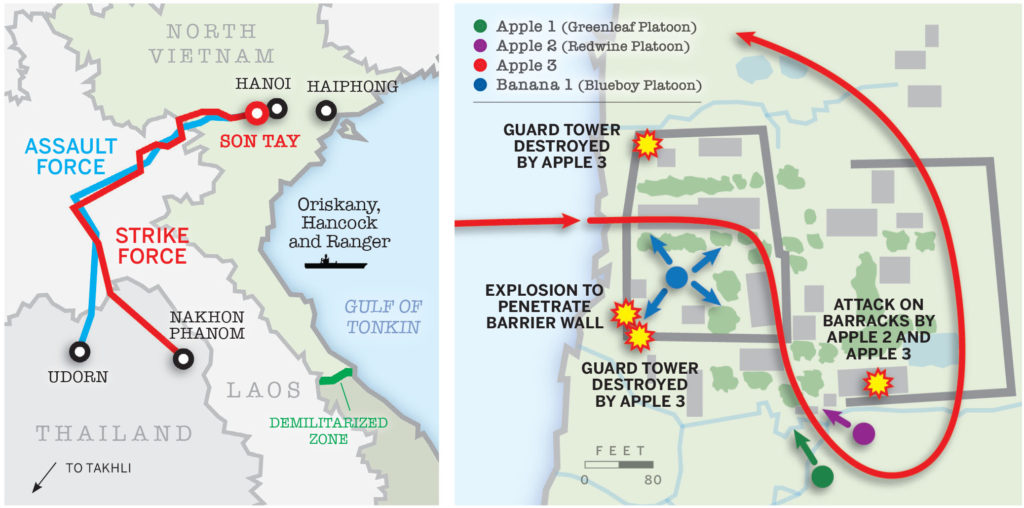

The prison, 23 miles northwest of Hanoi, was relatively isolated by a river bend with only one bridge to the north. About 12,000 enemy troops lurked at military facilities within a 15-minute drive. The raid was planned to take place within 26 minutes—before enemy reinforcements could be alerted and arrive.

The raiders would have about one minute on the ground to overwhelm guards near the prisoners. That one minute drove every planning decision.

A helicopter was needed to drop a main assault force inside the prison walls, which contained three guard towers and 40-foot high trees. The Air Force’s HH-53 “Super Jolly Green Giant” search and rescue helicopters were the best choice for inserting the raiders and returning the freed POWs. However, the HH-53 was too big to land inside the prison itself. A smaller helicopter, the UH-1 “Huey,” was selected to perform that task. Planners expected the UH-1’s rotor blades would be damaged from hitting a building while landing inside the compound, rendering it unable to take off again; the raiders would need to destroy the Huey instead.

Five propeller-driven A-1E Skyraider attack planes would circle above the prison to hold approaching ground forces at bay if needed. Two MC-130E Combat Talon transport planes, packed with highly classified equipment designed for precise navigation and stealth operations, would lead the Skyraiders, the Huey and Super Jolly helicopters to the prison.

Attacking at night, a one-quarter moon just above the horizon would offer good visibility while still providing night cover in clear skies. These conditions determined the time window for the prison raid—two five-day periods in late October and late November, predicted to be the driest months.

Air Force Brig. Gen. LeRoy Manor was appointed overall mission commander. Manor and Simons, his Army counterpart, decided all raiders would be volunteers. Simons interviewed about 200 men at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, asking questions designed to obscure mission details, such as: “Have you ever had scuba training?” At 20, Buckler was the youngest raider of the 82 enlisted men and 15 officers selected for training. When he was asked to make a will before he left, the sergeant realized this mission would be somewhat different from previous operations.

Manor had an especially difficult task. He had to coordinate the planning with Air Force special operators strung across Florida, South Carolina and Germany. He also needed crews for four types of aircraft. But Manor had no problem recruiting volunteers, even though he told them only they would be flying a dangerous mission.

Except for a handful of senior officers and planners, the raiders had no idea where they were going or exactly what they would do. Two counterintelligence agents constantly monitored the activities of the team, listening in on phone calls and rifling through trash cans to make sure no information leaked.

Training began in September at Eglin Air Force Base’s Duke Field in the Florida Panhandle. The raiders practiced in a full-scale mock-up of the prison camp built from 2-by-4s and cloth so it wouldn’t show up on spy satellites that occasionally flew overhead. Because the North Vietnamese guards might be standing close to POWs, Simons insisted on accurate shooting.

Some creative supply troops purchased night scopes advertised in a hunting magazine, with the result that the raiders’ accuracy dramatically improved. The CIA also provided a more detailed model of the prison camp on a large sheet of plywood. The CIA’s version, named “Barbara,” was so realistic that during the raid Buckler spotted a bicycle leaning against a building in the exact spot as on the model.

The ground plan called for three platoons consisting of 56 Special Forces soldiers in total. Blueboy Platoon, with 14 men, was the assault unit in the Huey that would blast a hole in the southwest corner of the wall for the POWs to escape through.

The 22-man Greenleaf Platoon in a Super Jolly would provide security support to the east and north, such as clearing buildings and blowing up the bridge. Redwine Platoon, the command party headed by Sydnor in another Super Jolly, was to secure the area to the south of the prison and prepare a landing area for the helicopter pickups. Buckler was assigned to Redwine as a radio operator. Each platoon trained for backup plans. If one team didn’t make it to Son Tay, the raid could still be executed.

The MC-130E Combat Talon planes and helicopter crews flew training routes around Florida, Georgia and Alabama. To lead the slower-moving helicopters, the MC-130E had to fly at 121 mph, nearly its stall speed. Some helicopters drafted in the wake of the plane’s wing so they could fly a bit faster than their normal power allowed.

The helicopters also could not climb at the faster speeds, so Maj. John Gargus, an MC-130E navigator, planned a route that began at a higher altitude and occasionally descended as the aircraft closed in on the target. However, the MC-130E’s radar and navigation equipment degraded at the slow speeds, so one of the planners borrowed two infrared devices from the CIA that helped reveal rivers and other landmarks no longer visible on the radar.

In the final training phase, the air and ground forces practiced together. During these rehearsals they discovered that after three hours of sitting inside the cramped Huey, Blueboy raiders had trouble straightening their legs and moving on the ground, making the one-minute time frame for subduing the guards impossible. The Huey was replaced with a larger HH-3E Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopter. However, the HH-3E would be such a tight fit inside the prison walls that the pilots would have to make a controlled crash into the compound.

As training progressed, Manor, the Air Force general, and Simons, the Army colonel, raced around Southeast Asia with other planners to set up the launch bases. The raiders would use aircraft already in Southeast Asia. Rather than having those aircraft assemble at one location—which might give the enemy a clue that something was in the works—the crews would go to different bases. The planners carried a letter from the Air Force’s chief of staff, four-star Gen. John D. Ryan, telling other commanders to support them with no questions asked.

Manor and Simons also met with senior Navy officers, who agreed to launch aircraft from three carriers, the USS Oriskany, Hancock and Ranger, in the Gulf of Tonkin. To draw the attention of North Vietnam’s anti-aircraft artillery and surface-to-air missiles away from Son Tay, the carriers would make a diversionary feint to Haiphong Harbor, about 60 miles from Hanoi.

Training was complete in early October. On Nov. 18, Nixon gave his final approval. The date was set for Nov. 21.

The two MC-130E Combat Talon crews had flown their aircraft from Eglin to Thailand the previous week. After the final go-ahead on Nov. 18, other raiders, who weren’t told where they were going, boarded a C-141 Starlifter troop transport plane at Eglin and 28 hours later landed in what the raiders surmised was Southeast Asia.

As the raiders’ aircraft waited for the final “go” signal for the raid, Typhoon Patsy threatened the Navy diversion. Rather than delay for five days, Manor moved the raid up to Nov. 20.

That evening, Gargus and the rest of his MC-130E crew, call sign Cherry 2, took off from Takhli at 10:25 p.m. and headed to their rendezvous point with the five A-1E Skyraiders. The A-1E pilots had a few anxious moments after takeoff when they encountered some clouds. Eventually they linked up with Cherry 2 for the trip to Son Tay.

About 11 p.m., Cherry 1, the Combat Talon that would lead the one HH-3E Jolly Green and five HH-53 Super Jolly helicopters, could not start one of its engines. Although the plane could take off on three engines, that would be very risky at night. Manor was monitoring the mission from a command center at South Vietnam’s Da Nang Air Base and was about to order Cherry 2 to lead the helicopters when Cherry 1’s engine finally started, according to Gargus. The plane took off about 23 minutes behind schedule.

The six helicopters that would conduct the rescue departed from Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base. Three—the one H-3E and two of the HH-53 copters—carried the assault force. The other three HH-53s were empty, a gunship and two for the returning POWs. The helicopters refueled over Laos and then joined with Cherry 1, which had made up for lost time. At about 1 a.m., Navy carriers began launching 59 fighter, attack and support planes. The pilots flew routes that seemed to indicate they were headed for targets around Hanoi. Several Air Force support aircraft were also airborne over the Gulf of Tonkin, providing radio relays and monitoring North Vietnamese radios and radars to ensure the raiders hadn’t been detected.

A little after 2 a.m., Air Force F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers with air-to-air missiles arrived at a high altitude above Son Tay to defend against possible launches of MiG fighters aiming for the raiders. F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers also arrived to take out any threatening SAM sites.

The diversion worked. As the raiders approached Son Tay, North Vietnamese radars pointed east at the diversionary Navy attack and at the overhead F-4s and F-105s. Equipment on the Combat Talon showed enemy radars routinely scanning but failing to detect the inbound raiders.

At 2:16 a.m. after three hours of flying, the assault formation aircraft arrived at their planned break-off point 3½ miles from Son Tay. Cherry 1 broadcast a final heading for the helicopters bound for the prison camp and then flew ahead. Two of the empty HH-53 helicopters landed nearby, waiting for the POW pickup call.

At 2:18 a.m., the “execute” command came over the radio: “Alpha! Alpha! Alpha!”

Cherry 1 arrived over the prison compound and dropped four flares bright enough to light up the camp below as if it were daytime.

Air Force Maj. Frederic “Marty” Donahue turned his empty HH-53 gunship to fly across the camp between two guard towers. He ignored a warning light that signaled an emergency engine problem as his gunners sprayed the guard towers at 4,000 rounds per minute, collapsing the critical southwest tower. The gunners then strafed other buildings. Tracer bullets ignited a fire in a barracks. The compound was ready for Blueboy’s HH-3E.

As the helicopters carrying the ground force moved toward their landing spots, Cherry 2 dropped flares and other incendiary devices outside the prison to create diversions for enemy soldiers in the area. It then entered an orbit a few miles south to monitor and record the raiders’ radio transmissions. Cherry 1 dropped additional diversion devices and flew to an orbit in northern Laos.

The two pilots flying the HH-3E Jolly Green Giant nearly landed a few hundred yards south of the prison in a similar-looking compound that planners called a “secondary school.” The pilots realized their mistake at the last second and corrected back to the prison. Blueboy raiders armed with personal sidearms, CAR-15 commando carbines, shotguns, M79 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns crouched by the helicopter’s doors and windows. Some raiders lay flat on the open ramp.

The HH-3E’s controlled crash inside the prison compound was much more violent than expected. When the rotors hit the trees, the helicopter jerked violently to the right and tossed 1st Lt. George Petrie out the right front door—granting his wish to be the first raider on the ground. He had extra motivation: His cousin, Navy Lt. Cdr. James Hickerson, was a POW.

The crash didn’t slow anyone down. As severed tree limbs rained all around, raiders attacked what was left of the southwest guard tower and prepared to blow the exit hole. Blueboy’s leader, Capt. Richard “Dick” Meadows, shouted on a bullhorn: “We are Americans! We are here to rescue you!”

The raiders broke into some cells but found no POWs. They kept searching.

Greenleaf Platoon’s pilot mistakenly touched down in the secondary school. Raiders poured from the helicopter and headed toward their targets, but quickly realized something was wrong. Simons, traveling with Greenleaf, called for an extraction. In the four minutes it took the helicopter to return from its holding area, the Greenleaf men obliterated the school compound’s occupants, armed men who seemed much larger than average Vietnamese and were possibly Chinese advisers or trainers.

Redwine Platoon’s pilot realized Greenleaf had landed in the wrong spot and broadcasted the backup plan on the helicopter’s intercom before landing outside the wall of the prison. While still on the helicopter’s ramp, Buckler fired his M16 at a guard shooting at Redwine raiders as they dashed to take over some of Greenleaf’s duties as well as their own. With the reduced ground force unable to take out the bridge to the north, orbiting Skyraider pilots happily dropped cluster bombs on it instead. A Redwine group blew up a concrete pole in the helicopter return area, and the explosion knocked out power in parts of Son Tay.

In the midst of the commotion, Greenleaf Platoon arrived. The raiders had never practiced a late arrival. There was momentary confusion as newcomers joined the fight. Sydnor ordered the Redwine raiders to momentarily hold their positions while they sorted things out.

By then, Buckler had heard the words “negative items” over his radio. The crews circling above or waiting in helicopters heard them as well. “Items” was the code word for POWs.

Negative POWs? Simons couldn’t believe it. “Check again,” he demanded. Simons followed this by a string of expletives and, “I’m coming in.”

Simons checked the cells and found no one.

At 2:30 a.m., 11 minutes into the raid, Sydnor called for withdrawal. The two lead HH-53s flew back to pick up the raiders, who left a charge with a time delay on the HH-3E to destroy it.

Meanwhile the North Vietnamese realized they were under attack. Radar detection equipment on Cherry 2 lit up as a North Vietnamese radar for anti-aircraft artillery targeted the plane. The pilot flew north to a safer position. At 2:35 a.m., the North Vietnamese near Son Tay launched their first SAMs at the raiders.

At 2:45 a.m., 26 minutes after the crash into the courtyard, an HH-53 lifted off with the last of the ground force. There was a brief scare when a count came up short one raider.

After a few anxious moments and several recounts, they realized no one had been left behind. The raiders suffered only two casualties: one Green Beret shot in the leg, the only “enemy fire” casualty, and an HH-3E crew member with a broken ankle from the controlled crash.

As the raiders departed Son Tay, SAMs filled the sky, hitting two F-105 Thunderchiefs. One was able to refuel and limp back to Udorn. The pilot and electronic warfare officer in the other aircraft ejected over Laos at 3:17 a.m. and Cherry 2 located them. Two of the empty HH-53s refueled, waited for first light, and picked up the downed crewmen, who had spent three hours on the ground.

The dejected raiders returned to Udorn for debriefing. Manor and Simons flew to Washington for a press conference on Nov. 23. The men emphasized the bravery of the raiders and the difficulty of pinpointing POW camps, but some in the press focused on the apparent intelligence failure. Later evidence showed that intelligence indicated the POWs had been moved, but that information hadn’t been conveyed to the final decision-makers—who at that time were only two hours from mission launch. The tight secrecy to prevent leaks was likely a contributing factor, according to Gargus.

Yet the raid was far from a failure. Shocked at how easily the raiders had slipped in and out of their country, the North Vietnamese consolidated the POWs into the notorious “Hanoi Hilton” prison to make future rescue attempts more difficult.

Ironically, the consolidation at the Hanoi Hilton was the best thing that could have happened for the prisoners, short of rescue. Retired Col. Leon “Lee” Ellis, one of the Son Tay POWs, says that during the raid the POWs knew something was up.

In their new camp about 10 miles away, the power went off, probably from the raiders accidentally knocking out power to the surrounding area. The POWs then heard explosions from Son Tay, followed by the SAM launches.

Two days later, guards came into the cells “with fear in their eyes” and moved the prisoners to Hanoi. POWs previously in solitary confinement now roomed with dozens of men. Senior officers organized a POW wing with a military chain of command. The POWs taught each other classes, had evening speakers and surreptitiously held church services.

For their actions, all raiders were awarded medals—Silver Stars and above—but some feared they had made things worse for the POWs.

The raiders finally learned the truth after the POWs were released in February-April 1973. Many POWs wanted to meet the Son Tay raiders to thank them for the positive impact they had. Billionaire Texas businessman Ross Perot brought the raiders and the Son Tay POWs to a thank-you party in San Francisco. The two groups have had many reunions since.

In 1979 Simons led the rescue of two of Perot’s employees from an Iranian prison. The planning and execution of the Son Tay Raid became a blueprint for special operations forces, such as the 2003 rescue of Army Pvt. Jessica Lynch, captured during the Iraq War, and the 2011 Osama bin Laden raid. V

Eileen Bjorkman is a retired Air Force officer, freelance writer and author of Unforgotten in the Gulf of Tonkin: A Story of the U.S. Military’s Commitment to Leave No One Behind. She lives in Edwards, California.

This article appeared in the December 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here: