The U.S. Army had assigned 1st Lt. Joseph Bonnell to witness the signing of an 1835 treaty of cession in which the Caddo Nation would sell all of its lands in the United States—nearly 1 million acres—for $30,000 in goods and horses as well as $10,000 in cash for five years.

Most of the Caddo lands were in Louisiana, though some were in disputed border territory and would become part of Texas when it achieved independence from Mexico the following spring. Before signing the treaty July 1, however, Bonnell asked U.S. Indian agent Jehiel Brooks, commissioner of the proceedings, for his permission to read the text. The agent refused, raising Bonnell’s suspicions.

UNFAIR AGREEMENT

After the signing Bonnell discovered a hidden provision inserted by Brooks that unjustly enriched the agent’s friends and Brooks by association. Such overt deception and theft went against the ethics Bonnell learned at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The lieutenant would not tolerate it and signed a deposition in favor of the Caddos against Brooks. His action in part prompted a lawsuit against the agent, which in 1850 worked its way to the Supreme Court in United States v. Brooks.

Bonnell’s sense of duty and honor in support of the Caddos got wide attention in military circles. It certainly caught the attention of Sam Houston, whom the Texas Army would commission a major general that November. Bonnell and Houston, whom a Cherokee chief had nicknamed the Raven (roughly pronounced Go-la-na in Cherokee), became friends. The incident also earned Bonnell the friendship of the Caddo chiefs—a relationship that proved of great benefit at the outset of the Texas Revolution.

WEST POINT GRADUATE

Bonnell was born in Philadelphia on Aug. 4, 1802. In 1821 the 18-year-old entered West Point as a cadet. As a first-class cadet (senior) in 1825 Bonnell demonstrated military aptitude and was appointed a cadet lieutenant. The sergeant major cadet that year was Albert Sidney Johnston, who was a year behind Bonnell. (Johnston would move to Texas in 1836 and enlist as a private in the Texas Army. He rose to assume command of the Army of the Republic of Texas on Jan. 31, 1837, and served as the republic’s secretary of war from 1838 to 1840.)

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Bonnell graduated with the 37 members of the West Point Class of 1825. On April 23, 1831, the lieutenant married Anna Elizabeth Noble of Adams County, Miss., and returned with his bride to Fort Jesup, La., near the disputed international border with Mexico, where Bonnell was stationed with the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment. In July 1835 he traveled to the Caddo Agency on Bayou Pierre, south of Shreveport, to witness the signing of the U.S.-Caddo treaty.

The Texas Revolution broke out Oct. 2 at the Battle of Gonzales, where besieged Texians flew their famed “Come and Take It” flag in defiance of Mexican army efforts to disarm them of their protective cannon. In the subsequent skirmish the Mexicans lost two soldiers before withdrawing. On Nov/ 22 Maj. Gen. Houston, commanding general of the Texas Army, selected Bonnell as his aide-de-camp, the provisional government of Texas approving the appointment in a resolution signed by the governor and lieutenant governor.

FRIENDSHIP WITH HOUSTON

On Dec. 30 Bonnell sent Houston a “how to start an army” letter that included detailed explanations and sample documents pertaining to uniforms, military administration, logistical supply, pay, promotions, ordnance, ammunition and rations. It was a blueprint for building the Texas Army. Bonnell signed the letter, “Your sincere friend, J. Bonnell.” On Jan. 11, 1836, Houston wrote provisional Governor James W. Robinson, urging Bonnell’s appointment as a captain in the Texas Army. He was so recognized in a list of officers issued on March 10.

In addition to the ongoing revolution, the threat of an American Indian war hung over Texas in early 1836. Prominent members of the convention that declared Texas’ independence on March 2 were opposed to granting land to Indians, nullifying an earlier peace treaty Houston had negotiated. The Kadohadacho Caddos in particular had considerable influence with other tribes, and the Mexicans commissioned an agent, Manuel Flores, to coax the Caddos to fight Texians, with promises of money and plunder.

By March 7 Caddo warriors, along with Nadacos, Hainais, Kichais and Wichitas, were reportedly stealing horses from white settlers. On that date Houston implored, for the safety of the frontier, the Cherokee treaty be ratified. It was not. His concerns that Indian depredations would increase unless the convention recognized American Indian lands fell on deaf ears.

In response Cherokee Chief Bowl assembled his warriors on the San Antonio road, east of the Neches, prepared to attack the Texians should the Mexican army prevail. At that critical juncture David G. Burnet, interim president of the republic, commissioned respected American Indian trader Michel B. Menard on March 19 to secure the neutrality of the tribes while avoiding any treaty relating to boundaries.

The next day John T. Mason of Nacogdoches sent a letter to Major J.S. Nelson, commandant of Fort Jesup, warning of the impending Indian attack, and asking, “Is it not in your power to send a messenger to them, particularly the Caddoes [sic], to make them keep quiet?”

Meanwhile, Houston’s army continued its Runaway Scrape eastward from the banks of the Colorado River to San Felipe on the Brazos River on March 26 and then across the Brazos to an encampment on the west bank opposite Groce’s Landing. If the American Indians were to aid the Mexican army, the Texians would be caught between two foes.

RABBLE ARMY

While encamped on the Brazos in early April, Houston valiantly sought to organize his motley rabble into an army. At the same time a Texian messenger rode to Fort Jesup carrying a letter that explained the Indian threat in Texas.

On April 4 Maj. Gen. Edmund Pendleton Gaines, commander of the U.S. military district, arrived at Fort Jesup to take command, but due to the strained nature of diplomatic relations with Mexico, he could not take any overt action in support of the Texas Revolution. What he did do was send Lieutenant Bonnell to parley with the Indians (his written order is dated April 7, though a vocal order may have preceded it).

Both the U.S. Army and Sam Houston thought highly of Bonnell, who as a U.S. first lieutenant, captain in the Army of the Republic of Texas and military aide to the Texian commander was uniquely positioned.

Gaines authorized Bonnell to employ an interpreter and the quartermaster to pay any of the lieutenant’s related expenses. Bonnell’s task: Travel to the Caddo villages in east Texas to quell a possible uprising. Few officers have ever been assigned such a daunting mission. Gaines was also out on a limb. Sending a U.S. Army officer across the border into country at war with fellow Americans was a most unusual and risky course of action.

In the general’s written orders he directed Bonnell to learn whether Caddo warriors were in Texas, determine their disposition toward white inhabitants and urge them to remain at peace. Should he manage to return alive, Bonnell could then apprise the Texians, still encamped opposite Groce’s Landing on the Brazos, of any hostile Indian movements.

Although there is no record the infantry officer used horses on his mission, Bonnell almost certainly did, given the ground he had to cover.

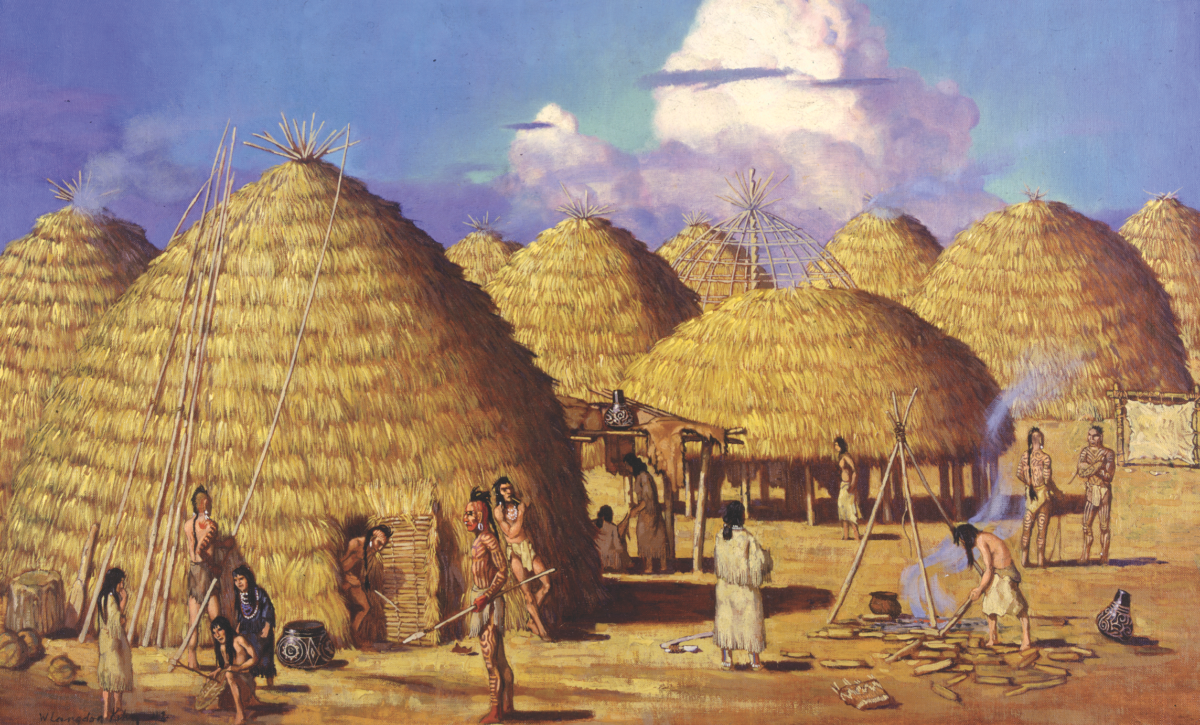

The four villages of the Kadohadacho Caddos were at the northwestern tip of Caddo Lake, south of present-day Smithland; the Nadaco Caddo village was on the Sabine River south of present-day Longview; and the Hainai Caddo village was on the Angelina River 15 miles west of Nacogdoches. Bonnell likely set out with Caddo Lake in mind, as reports received at Fort Jesup indicated the Kadohadacho warriors posed the greatest threat.

DELICATE MISSION

Meanwhile, agents dispatched from Nacogdoches to Shawnee, Delaware and Kickapoo villages some 75 miles north of town learned that the Cherokees had asked them to take up arms against the Americans. C.H. Sims reported that some 1,700 Caddos, Kichais, Hainais, Tawakonis, Wacos and Comanches had amassed, and that the Cherokees, who had already murdered trader Brooks Williams, gave every indication they would join the other tribes.

William Sims, who lived near a Cherokee village, also testified to their hostile intentions and willingness to join the other tribes. The combined army of Indians, which outnumbered the entire Army of the Republic of Texas, was within 75 to 200 miles of Houston’s position and within 72 hours could deliver a fatal blow to the general’s tiny army.

Houston was so concerned about the American Indian threat that on April 13 he wrote his Cherokee friend Chief Bowl. His letter is notable in two respects: First, it grossly underreports the strength of the Mexican army, and second, it includes a promise impossible for the general to keep. Houston told Bowl there are “not many of the enemy in the country” and assured the chief, “You will get your land as it was promised in our treaty.”

The letter is flush with words of brotherly love uncharacteristic of Houston. Recognizing the American Indian threat, it is likely the general hoped to mislead his friend turned potential enemy regarding Texian intentions.

En route to the Caddos Lieutenant Bonnell heard of Mexican agent Manuel Flores’ efforts to persuade the Caddos to make war on the Texians. On reaching an all but deserted Caddo village on April 14, Bonnell learned from the few remaining Indian women that “their warriors had gone to the prairies in consequence of what Manuel Flores had told them, viz: that the Americans were going to kill them all.”

At a second Caddo village a dozen miles away (probably north of Caddo Lake and south of present-day Smithland) he found several warriors, including Chief Cortes, “a very intelligent Indian…said to have great influence with his nation.” Doubtless Cortes was stunned to find a uniformed U.S. officer in their midst in Texas, where the Army was not supposed to be.

Bonnell explained that he had come as a friend, that the Americans were the Caddos’ friends, and that his superiors desired the warriors to return to their villages and live and hunt in peace. When Bonnell asked what reply he should take to Gaines, Cortes answered, “Tell General Gaines, the great chief, that even if the Caddos should see the Spaniards and Americans fighting, they would only look on but take no part on either side; tell him that I will send and let the nation know what you have told me.”

REPUTATION FOR HONESTY

Cortes added that he was glad Bonnell had come, realized Flores had been feeding his people lies and would eagerly pursue peace. Clearly, the reputation for honesty the lieutenant had earned during the U.S.-Caddo treaty negotiations was paying dividends.

Bonnell then returned to the first village, where he found “another very intelligent Indian, part Spaniard,” who told him that Flores, passing himself off as a Mexican officer authorized to enlist the Caddos to fight the Texians, had passed through the village and was at that moment with the warriors on the prairie.

By April 16 Cortes’ message from Bonnell would have reached the Caddo war parties in the field. That morning Houston’s army decamped from Sam McCarley’s plantation (west of present-day Tomball) and began the march that led to the Battle of San Jacinto just five days later. That the route to San Jacinto was clear was a testament to Bonnell, who had single-handedly defused the looming Indian threat against the Texians.

On April 20, the day before the battle, Bonnell returned to Fort Jesup and officially reported to Gaines that the Caddos would not make war against the Texians, despite the best efforts of Mexican agent Flores. (In 1839 Texas Rangers would chase down and kill Flores on the banks of the North San Gabriel River as he sought to deliver war material to the Cherokees.)

During the decisive battle of the Texas Revolution, Gen. Houston carried as his only weapon a sword given him by friend Joseph Bonnell. The Houston/Bonnell sword is on display at the Sam Houston Memorial Museum [samhouston memorialmuseum.com] in Huntsville. On learning of the Texian victory at San Jacinto, Gaines sent Bonnell’s report to U.S. Secretary of War Lewis Cass, who forwarded it to President Andrew Jackson. Today it is housed among the executive documents of the U.S. Congress.

In 2005 the Texas Legislature adopted a resolution paying tribute to the memory of Lieutenant Joseph Bonnell, unsung hero of the Texas Revolution, and commemorating his significant contributions toward securing Texas’ independence. That Memorial Day weekend an honor guard from his old unit, the 3rd Infantry Regiment (aka the “Old Guard,” which now escorts the president of the United States and guards the Tomb of the Unknowns in Arlington National Cemetery, among other ceremonial duties), traveled to Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery to extend Bonnell full military honors on the dedication of a historical marker at his grave site. The marker reads as follows:

“On April 7, 1836, Lieutenant Joseph Bonnell, West Point Class of 1825, 3rd Infantry Regiment, U.S. Army, Fort Jesup, Louisiana, was sent alone into Texas by U.S. General Gaines to quell an uprising of 1,700 hostile Indians which threatened the small Texas Army of Gen. Sam Houston. Lieutenant Bonnell completed this dangerous mission by successfully negotiating with Caddo Chief Cortes to have the warriors return to their villages and live in peace. Bonnell’s success greatly assisted Houston’ Army in prevailing at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. Captain Joseph Bonnell, who died on September 27, 1840, was the only active duty U.S. Army officer who was a Hero of the War for Texas Independence.”

This story was originally published in Wild West in February 2017.

By Seldon B. Graham Jr.

Seldon B. Graham Jr. writes from Austin, Texas. The author thanks Stan Bacon, Fred Bothwell and Dan Hickox, all graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, for their assistance with this article. Suggested for further reading: The Caddo Indians: Tribes at the Convergence of Empires, 1542–1854, by F. Todd Smith. To learn more visit www.west-point.org/joseph_bonnell.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.