The “Londoner’s Diary” section on Page 2 of the Jan. 7, 1944, Evening Standard included what to citizens of the bomb-ravaged British capital must have seemed a rather uninteresting news item. Under the heading Still Empty it read in part: “Down in Chelsea two rows of houses in Sloane Court were requisitioned over three months ago. Tenants had to pack up and find other accommodation. The flats are still empty.” Six months later those former residents had reason to give thanks they no longer lived at Sloane Court. The same could not be said for the military service personnel who had displaced the tenants, many of whom belonged to the U.S. Army’s 130th Chemical Processing Company.

Shortly before 8 a.m. on Monday, July 3—just shy of a month after the Allied D-Day landings in Normandy, France—a German V-1 flying bomb struck the residential Chelsea street, causing massive destruction and killing dozens of soldiers and several civilians. It marked the single worst incidence of loss of life for American servicemen due to a V-1 blast and the second worst V-1 incident in London during the war.

The word “bomb,” when referring to a device carried and dropped by an airplane during World War II, generally conjures an image of an explosives-packed cylindrical shell with stabilizing fins at its tail and no internal guidance system. Such a description is grossly inadequate when describing a V-1 and how it functioned.

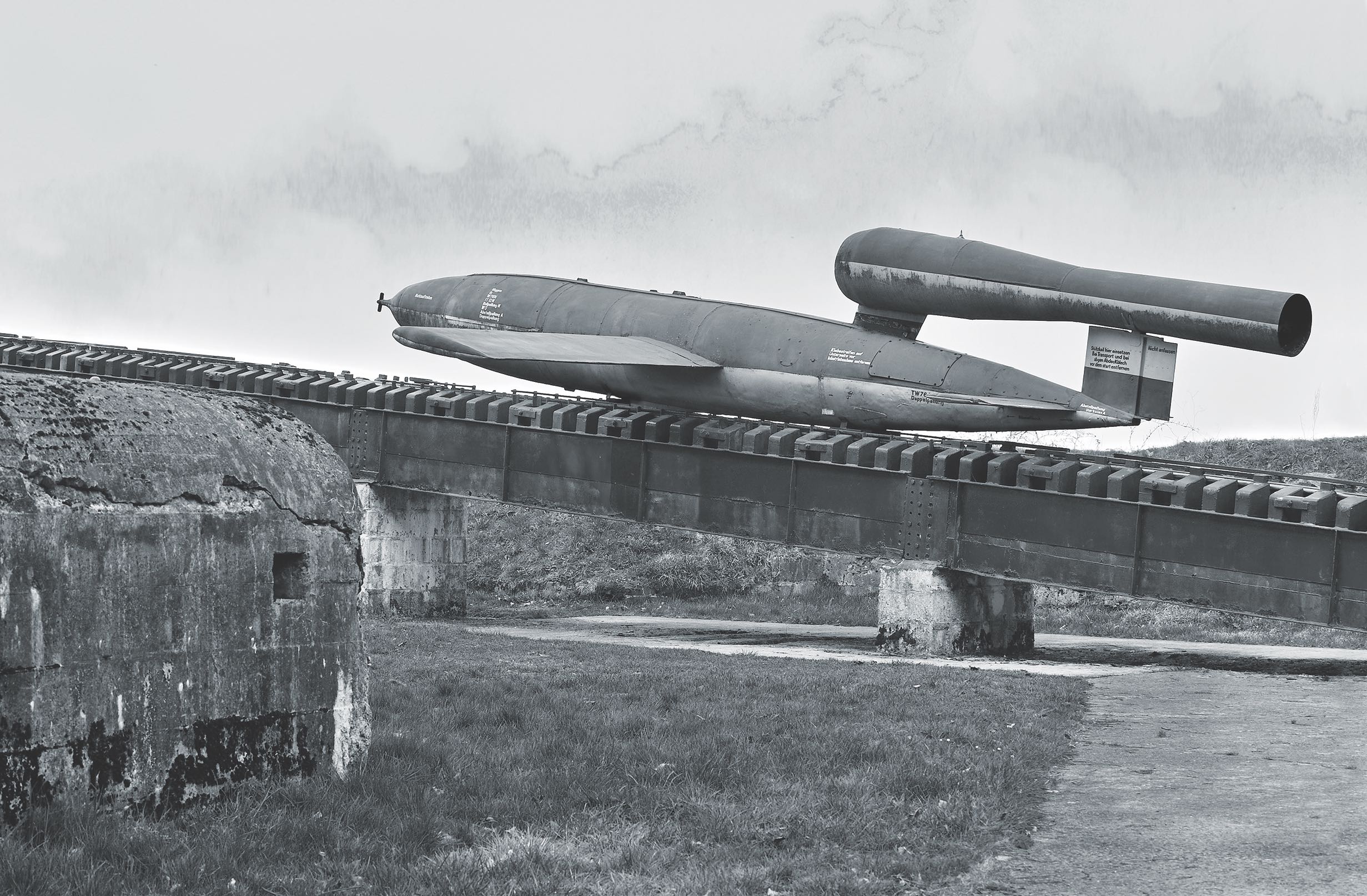

Purportedly launched by Adolf Hitler in retribution for the devastating Allied bombing campaign against German cities and towns, and precipitated by the D-Day landings, the V-1 was the first in a proposed series of Luftwaffe Wunderwaffen (“wonder weapons”). The “V” stood for Vergeltungswaffe (“retaliatory weapon”), a role for which the V-1 was well suited. It was an ingeniously designed pilotless aircraft, more than 27 feet long and weighing 4,740 pounds. Propelled by a gasoline-fueled pulse-jet engine with a top speed of 400 mph and an operational range of 160 miles, it carried a warhead packed with 1,870 pounds of Amatol, a high-explosive mix of TNT and ammonium nitrate. Catapulted from an inclined launch ramp pointed roughly toward its target, the V-1 relied on a guidance system comprising gyroscopes, a magnetic compass, barometer, vane anemometer and an odometer. The flying bomb maintained a cruising altitude of around 2,000 to 3,000 feet until it reached the vicinity of its target, when a cutoff device set the rudder in neutral, putting the V-1 into a steep terminal dive.

The device flew too fast for most piston-engined aircraft to catch and too fast for anti-aircraft gunners to get a good bead on it, and when Allied planes and ground guns opened up on an inbound V-1 at the same time, the result was often catastrophic. “The AA guns were supposed to stop firing once they picked up any fighters chasing the V-1s,” British historian Graham Thomas writes in his history of the flying bomb, Terror From the Sky, “but in many cases they didn’t, and some good, experienced pilots were lost because of it.”

The V-1 so closely resembled a piloted plane that Allied spotters frequently mistook it for one—until they heard telltale sounds emanating from it. Its pulse-jet engine emitted a staggered, popping noise variously described like that of “a Model T Ford going up a hill” or “a motorbike without a silencer.” In a post–V-E Day letter to his mother Sgt. Eric Stern of the G-5 Division of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), who was billeted on Sloane Court at the time of the bombing, wrote, “They sounded like outboard motors on small boats, kind of irregular.”

The V-1’s telltale engine stutter prompted the Allied nickname “buzz bomb” or “doodlebug.” Once the cutoff device sent the flying bomb diving toward its target, however, its engine stopped, and replacing the buzz was a terrifying 10 to 12 seconds of silence as the V-1 plunged to earth. “The dreaded moment,” wrote Stern, “was when the motor cut out. Then you could look for cover, count to 5 or 10 and hope it wouldn’t hit you.”

Germany launched the first wave of V-1s against London on June 13, 1944. Although many of the flying bombs never reached their targets, either crashing or being downed by Allied air and ground defenses, thousands more were successful. More than 2,400 of the weapons struck London, resulting in massive destruction of property and the loss of some 6,200 lives. Nor was Britain the only target; Germany launched flying bombs into Belgium up until just weeks before its May 1945 surrender. They caused stunning devastation, killing some 5,000 people, mostly in Antwerp, Brussels and Liège, in a last-ditch attempt to stop the Allied advance. “It was,” says Tom Hopkins, a curator at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford, “a pretty ferocious beast.”

One such beast fell on Sloane Court in early July 1944.

At the time of the attack more than 1.5 million American military personnel were posted in Britain and Northern Ireland. In London, where Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower himself was headquartered, accommodations for U.S. troops honeycombed the city. Some were in the brick buildings lining the Chelsea district street known as Sloane Court. “The respectable brick apartments spanning the residential lane were now practically a barracks,” writes Jamie Holmes, author of 12 Seconds of Silence. “Twenty prime addresses there were set aside for American soldiers.”

Among the units billeted along Sloane Court was the 130th Chemical Processing Company. It had arrived in London on May 7, a month before D-Day, and outwardly resembled an average Army company. Its roughly 150 soldiers ranged in age from their late teens to mid-30s and came from cities and towns across the United States. That was where the similarity ended. The highly trained 130th was assigned the specialized task of addressing chemical warfare.

Thus far Germany’s shells and bombs, while destructive, had been limited to conventional explosives. Early in the war, however, senior American leaders had considered the possibility Hitler might unleash devices with chemical or biological warheads. By January 1944 the prospect Germany would resort to such weapons loomed ever larger in the minds of U.S. commanders. The federally appointed Joint New Weapons Committee conveyed its very real concerns to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the enemy’s new raft of Vergeltungswaffen might include such lethal agents as botulism, anthrax and that highly effective holdover from World War I, mustard gas. In 1942 the Army had established a vast training base in Alabama, dubbed Camp Sibert, as the nation’s first chemical weapons training facility. As the tide of the war shifted, the post assumed ever increasing significance. “The purpose of the 37,000-acre camp of rolling Alabama farmland,” Holmes writes, “was to provide ample space for large-scale ‘live agent’ training.”

It was on that rolling farmland the officers and men of the 130th received their training, which was beyond intensive. Camp Sibert featured, among other things, a chemical mine testing area, a 6-square-mile toxic gas yard and flyover simulated chemical air attacks. Soldiers were trained to decontaminate virtually everything a chemical weapon might taint—including their own uniforms. “In case of a gas attack,” Holmes writes, “the 130th had the job of protecting Allied troops by infusing their clothing with defensive chemicals.” Part of this process involved impregnating the clothes in a “secret chemical formula that included chlorinated paraffin.”

The unit had been activated in April 1943 as the 130th Chemical Impregnating Company, and over the course of their training its original members had formed close friendships, despite the disparity in age, prewar occupations, prior military experience and educational status. By the time they arrived at their London billets at Nos. 4, 6 and 8 Sloane Court East, they constituted a tightly knit, well-trained unit that had already received a letter of commendation for its “zeal and industriousness.”

The 130th was not the only U.S. unit billeted on or near Sloane Court. Men of the G-5 Division of Eisenhower’s SHAEF had also taken up residence on the street, as had members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Given the crowded conditions in the neighborhood’s air raid shelters, U.S. military residents were precluded from sleeping or sheltering in them. “Most of us, however, were fatalistic about the Doodlebugs,” Stern recalled. “There wasn’t really anything we could do about protection.”

On arrival in London that June celebrated swing trombonist Glenn Miller and his 50-member big band had been billeted on Sloane Court, but the frequency of V-1 strikes in the neighborhood led him to request a change of address. According to Miller biographer George T. Simon, in those early weeks of the V-1 campaign Sloane Court acquired the epithet “Buzz Bomb Alley.” Miller was either prescient or extremely lucky. He and his band members left Sloane Court for Bedford, England, on July 2—the day before the bombing.

Shortly after their arrival in London the men of the 130th had set up a chemical impregnation plant in a warehouse on Crinan Street, 5 miles north in the King’s Cross district. New to the city’s stringent air raid procedures, they were soon helping locals clear away rubble and search for survivors in the wake of V-1 attacks. That was how they had spent the weekend of July 1 and 2. By 7:47 on the hazy Monday morning of July 3 they had finished breakfast and were preparing to board trucks for work when their world exploded.

Most men of the 130th were standing around outside their buildings while the first group boarded their waiting truck. Suddenly, a V-1 plummeted silently out of the haze. The company commander and several other men spotted it and in the seconds before impact shouted, “Buzz bomb! Buzz bomb!” saving lives with their frantic warning. Some of the soldiers standing on the sidewalk ducked into the cellars of their buildings, while others dashed around the corner. Those seated in the back of the truck had no chance to react; the V-1 blast blew the truck into the side of a building, killing all inside.

Eighteen-year-old Massachusetts native Samuel Edward Hatch was luckier than most. Delayed by cleaning chores, he had just left his quarters to board the first truck, but found it already full. Just then the V-1 appeared overhead. Running into an adjacent street, Hatch “fell facedown on the pavement with my arms outstretched.” As he recalled some 70 years later, “If there had been room for one more soldier on that truck outside, I would have met the same fate.” Injured by the blast, Hatch was taken to a medical facility.

Men like him who had run around the corner proved more fortunate than those who had sought shelter in the cellars. The bomb completely destroyed No. 6, and severely damaged the buildings to either side, killing many inside and trapping others below street level—some for hours, one man for four days. Exacerbating the situation, the explosion started a fire that burned a number of those trapped inside the buildings.

The building housing the G-5 soldiers also suffered major damage. Stern had been seated atop the second-floor staircase when the V-1 struck. “I never heard or saw a thing until several seconds after it happened,” he recalled in the letter home, written a year to the day after the bombing. “Then I found myself lying on the floor, covered with parts of the ceiling, wall and a large painted window.…I couldn’t move, because some soldier was lying across my legs moaning like mad. Personally, I looked like a mess. My uniform was torn to pieces, I was bleeding from several places, and my right hand was covered with blood and quite painful.…Almost all of the staircase had crashed in, except the part where I had been.”

The street was a nightmarish jumble of debris and bodies. RAF gunner Bill Figg was on leave in his home district and witnessed the grisly aftermath. “I saw this big Army truck with four bodies slumped over the back,” he recalled. “In the middle of the road there was a head. All down Sloane Court East there were more bodies than you could shake a stick at.”

Within minutes rescue squads, honed to rapid response during the years-long Blitz, were on scene. Some fortunate men of the 130th and G-5 stumbled from the wreckage with only minor injuries. Others—those rescuers could find—had to be carried out. Stern’s friend and co-worker had miraculously survived a three-story fall to the street, albeit with cuts, bruises and two badly broken legs. Stern helped carry his inexplicably conscious friend to an ambulance. “I went along with the same ambulance,” Stern himself recalled, “as I was getting a little weak, probably due to shock and loss of blood.” After receiving morphine and plasma at a first aid station, they were transported to a civilian hospital. At one point Stern called their commanding officer to explain why “we couldn’t make it to the office today.”

The WACs’ quarters had also taken a hit. A year after the bombing the Chicago Tribune published WAC Sgt. Jean Castles’ account of the bombing. “All we heard was what we thought was a motorcycle swishing by,” she told the reporter. “Then hell broke loose. That is the only way it can be put. The building not only rocked; it did ground loops. [My roommate] dashed from the window over to me, as the concussion had knocked me against the closed door. I picked myself up, and we began jamming each other under the bed, thinking the ceiling would collapse. Plaster fell, and the floorboards came up, one at a time, but our room was lucky.” They emerged to the same horrific scene. “I have never seen so much blood in my life—and disconnected arms and legs,” Castles recalled. “We collected all the blankets we could find to cover bodies and parts of bodies.”

The human cost of the Sloane Court bombing was high. Owing to wartime censorship and official reluctance to let the Germans know the extent of their bombs’ effectiveness, the number of fatalities and other details were not released to the public. As near as can be determined, 66 servicemen perished. Sixty-two were members of the 130th, three served in G-5, and one was a member of SHAEF’s 2nd Civil Affairs Unit. Dozens more service members were injured, including WACs. Among the nine British civilians killed was a female air raid warden.

Like much of the rest of war-torn greater London, Sloane Court has been completely rebuilt, and today it is a fashionable and desirable address. The only indication of the tragedy that befell American military personnel billeted in the neighborhood on July 3, 1944, is a pair of memorial plaques. Privately funded and installed in 1997 and 1998—one on Sloane Court and the other around the corner on Turk’s Row—they briefly detail the event and its mortal toll.

A few years after the bombing philosopher and poet Edward Pols—an Army lieutenant who had witnessed the aftermath—wrote “Elegy: The Walk Between (July 1944)” in commemoration. One section relates in graphic but evocative detail a specific heartbreaking moment:

In Turk’s Row one of our six-by-sixes

waited, piled high with dead open to any view,

till an old Coldstream major who stood by—

his head held erect by a leather brace—

spoke to the driver, who then dropped the canvas

flap to hide that sight which did no honor

to young men who just yesterday were quick

and in their grace. When the makeshift hearse—ready

to leave for some unit tasked with the dead—

came to life and crept through the dazed watchers,

the Coldstreamer moved to solemn attention

and salute; our young man next; then others

in uniform one by one; and all stayed

so, till riverwards the hidden burden passed

from sight. Each then turned, this small honor paid,

back to his own living lot that war had cast. MH

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to Historynet publications. For further reading he recommends 12 Seconds of Silence: How a Team of Inventors, Tinkerers and Spies Took Down a Nazi Superweapon, by Jamie Holmes, and Hitler’s Terror From the Sky: The Battle Against the Flying Bombs, by Graham A. Thomas. For his scholarly research, as well as his detailed account of all aspects of the Sloane Court bombing, the author thanks Alex Schneider, grandson of U.S. Army veteran and Sloane Court survivor Samuel Edward “Eddie” Hatch and strongly recommends a visit to Schneider’s comprehensive website [londonmemorial.org].