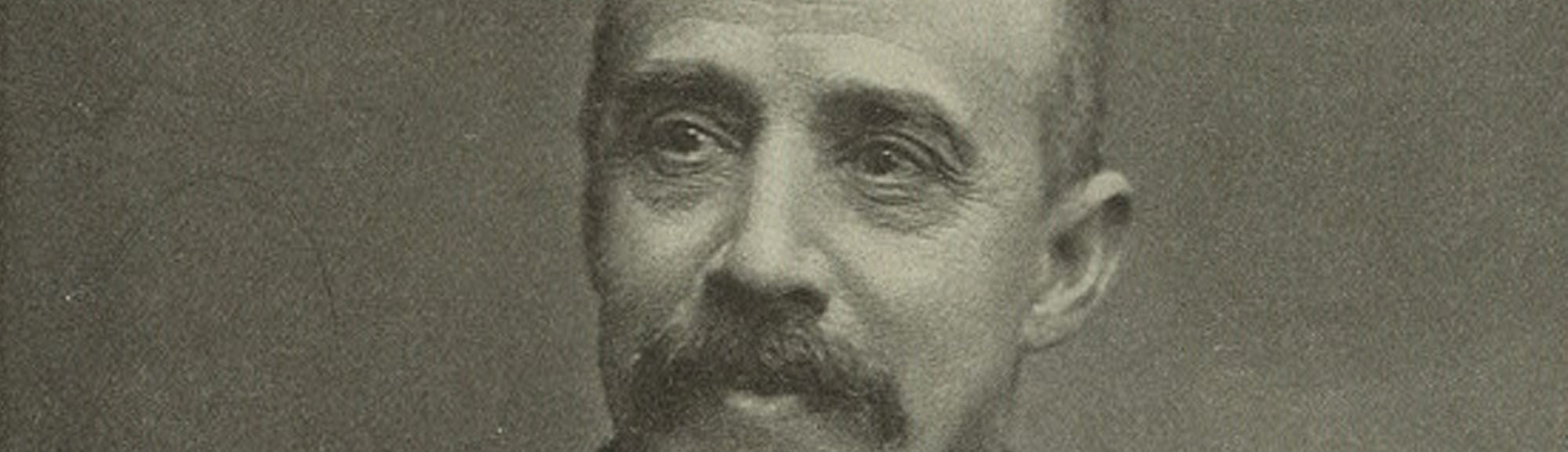

Paul Belloni Du Chaillu’s inside look at the African slave trade.

In 1856 the French-American adventurer Paul Belloni Du Chaillu set out on a journey through Africa that lasted four years and covered some 8,000 miles. His descriptions of gorillas, cannibals and Pygmies in Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa created a sensation when the book was published in 1861, the year the Civil War broke out, and may have inspired Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan series a half century later. He also provided one of the most vivid eyewitness accounts of the slave trade in West Africa. In the following excerpt he chronicles a visit he made in 1856 to Cape Lopez, on the coast of Gabon, where locals and the Portuguese conducted a brisk business selling slaves for markets in Brazil and Cuba.

A ball was given by the king in my honor. The room where I had been first received was the ball-room. When I arrived, shortly after dark, I found about 150 of the king’s wives assembled, many of whom were accounted the best dancers in the country. Shortly afterward singing began, and then a barrel of rum was rolled in and tapped. A good glassful was given to each of the women, and then the singing recommenced. In this the women only took part, and the airs were doleful and discordant.

A ball was given by the king in my honor. The room where I had been first received was the ball-room. When I arrived, shortly after dark, I found about 150 of the king’s wives assembled, many of whom were accounted the best dancers in the country. Shortly afterward singing began, and then a barrel of rum was rolled in and tapped. A good glassful was given to each of the women, and then the singing recommenced. In this the women only took part, and the airs were doleful and discordant.

When everybody was greatly excited with these songs, the king, who sat in a corner on a sofa with some of his favorite wives next him, gave the signal for the dance to begin. Immediately all rose up and beat a kind of tune or refrain to accompany the noise of the tam-tams or drums. Then six women stepped out and began to dance in the middle of the floor. The dance is not to be described. Any one who has seen a Spanish fandango, and can imagine its lascivious movements tenfold exaggerated, will have some faint conceptions of the postures of these black women.

The next day I made a visit to the barracoons or slave pens. Cape Lopez is a great slave depot—once one of the largest on the whole coast—and I had, of course, much curiosity to see how the traffic is carried on.

The first slave factory I visited was, from the outside, an immense enclosure, protected by a fence of palisades twelve feet high, and sharp-pointed at the top. Passing through the gate, which was standing open, I found myself in the midst of a large collection of shanties surrounded by shade-trees, under which were lying about, in various positions, people enough to form a considerable African town.

An old Portuguese, who seemed to be sick, met and welcomed me, and conducted me to the white men’s house, a two-story frame building, which stood immediately fronting the gate. The house was surrounded by a separate strong fence, and in the spacious yard which was thus cut off were the male slaves, fastened six together by a little stout chain which passed through a collar secured about the neck of each. It is rare that six men are unanimous in any move for their own good, and it is found that no attempts to liberate themselves, when thus fastened, succeed.

Beyond this yard was another for the women and children, who were not manacled, but allowed to rove at pleasure through their yard, which was also protected by a fence. The men were almost naked. The women wore invariably a cloth about their middle.

Outside of all the minor yards, under some trees, were the huge caldrons in which the beans and rice, which serve as slave food, were cooked. Each yard had several Portuguese overseers, who kept watch and order, and superintended the cleaning out of the yards, which is performed daily by the slaves themselves. From time to time, too, these overseers take the slaves down to the seashore and make them bathe.

I remarked that many of the slaves were quite merry, and seemed perfectly content with their fate. Others were sad, and seemed filled with dread of their future; for, to lend an added horror to the position of these poor creatures, they firmly believe that we whites buy them to eat them. They can not conceive of any other use to be made of them; and where the slave-trade is known in the interior, it is believed that the white men beyond sea are great cannibals, who have to import blacks for the market. Thus a chief in the interior country, having a great respect for me, of whom he had often heard, when I made him my first visit, immediately ordered a slave to be killed for my dinner, and it was only with great difficulty I was able to convince him that I did not, in my own country, live on human flesh.

The next morning I paid a visit to another slave factory. It was a neater place, but arranged much like the first. While I was standing there, two young women and a lad of fourteen were brought in for sale, and bought by the Portuguese in my presence. The boy brought a twenty-gallon cask of rum, a few fathoms of cloth, and a quantity of beads. The women sold at a larger rate. Each was valued at the following articles, which were immediately paid over: one gun, one neptune (a flat disk of copper), thirty fathoms of cloth, two iron bars, two cutlasses, two looking-glasses, two files, two plates, two bolts, a keg of powder, a few beads, and a small lot of tobacco. Rum bears a high price in this country.

At two o’clock this afternoon a flag was hoisted at the king’s palace on the hill, which signifies that a slaver is in the offing. It proved to be a schooner of about 170 tons’ burden. She ran in and hove to a few miles from shore. Immediately I saw issue from one of the factories gangs of slaves, who were rapidly driven down to a point on the shore nearest the vessel. I stood and watched the embarkation. The men were still chained in gangs of six, but had been washed, and had on clean cloths. The canoes were immense boats, managed by twenty-six paddles, and carrying besides each about sixty slaves. Into these the poor creatures were now hurried, and a more piteous sight I never saw. They seemed terrified almost out of their senses; even those whom I had seen in the factory to be contented and happy, were now gazing about with such mortal terror in their looks as one never sees nor feels very often in life. They had been content to be in the factory, where they were well treated and had enough to eat. But now they were being taken away, they knew not whither, and the frightful stories of the white man’s cannibalism seemed fresh in their minds.

But there was no time allowed for sorrow or lamentation. Gang after gang was driven into the canoes until they were full, and then they set out for the vessel, which was dancing about in the sea in the offing.

And now a new point of dread seized the poor wretches, as I could see, watching them from the shore. They had never been on rough water before, and the motion of the canoe, as it skimmed over the waves and rolled now one way now another gave them fears of drowning, at which the paddlers broke into a laugh, and forced them to lie down in the bottom of the canoe.

I said the vessel was of 170 tons. Six hundred slaves were taken off to her, and stowed in her narrow hold. The whole embarkation did not last two hours, and then, hoisting her white sails, away she sailed for the South American coast. She hoisted no colors while near the shore, but was evidently recognized by the people on shore. She seemed an American-built schooner. The vessels are, in fact, Brazilian, Portuguese, Spanish, sometimes Sardinian, but oftenest of all American. Even whalers, I have been told, have come to the coast, got their slave cargo, and departed unmolested, and setting it down in Cuba or Brazil, returned to their whaling business no one the wiser. The slave-dealers and their overseers on the coast are generally Spanish and Portuguese. One of the head men at the factories here told me he had been taken twice on board slave vessels, of course losing his cargo each time. Once he had been taken into Brest by a French vessel, but by the French laws he was acquitted, as the French do not take Portuguese vessels. He told me he thought he would make his fortune in a very short time now, and then he meant to return to Portugal.

The slave-trade is really decreasing. The hardest blow has been struck at it by the Brazilians. They have for some years been alarmed at the great superiority in numbers of the Africans in Brazil to its white population, and the government and people have united to discourage the trade, and put obstacles in the way of its successful prosecution. If now the trade to Cuba could also be stopped.

A pregnant sign of the decay of the business is that those engaged in it begin to cheat each other. I was told by Portuguese on the coast that within two or three years the conduct of Brazilian houses had been very bad. They had received cargo after cargo, and when pressed for pay had denied and refused. Similar complaints are made of Cuban houses; and it is said that now a captain holds on to his cargo till he sees the doubloons, and takes the gold in one hand while he sends the slaves over the side with the other. While the trade was brisk they had no occasion to quarrel. As the profits became more precarious each will try to cut the other’s throat.

Originally published in the August 2013 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.