South Korea’s most famous cartoonist cut his teeth as an artist in the early 1950s while war raged through—and devastated—his homeland.

Seventeen-year-old Kim Seong-hwan was sitting with a friend on a hill on the edge of Seoul and watching as a seemingly endless convoy of North Korean tanks approached the city on June 25, 1950. Although they could see puffs of gray smoke from artillery on the horizon, the two teenagers weren’t worried. “We had heard over the radio that North Korea had invaded,” Kim later recalled, “but were told that the South Korean Army was pushing them back.”

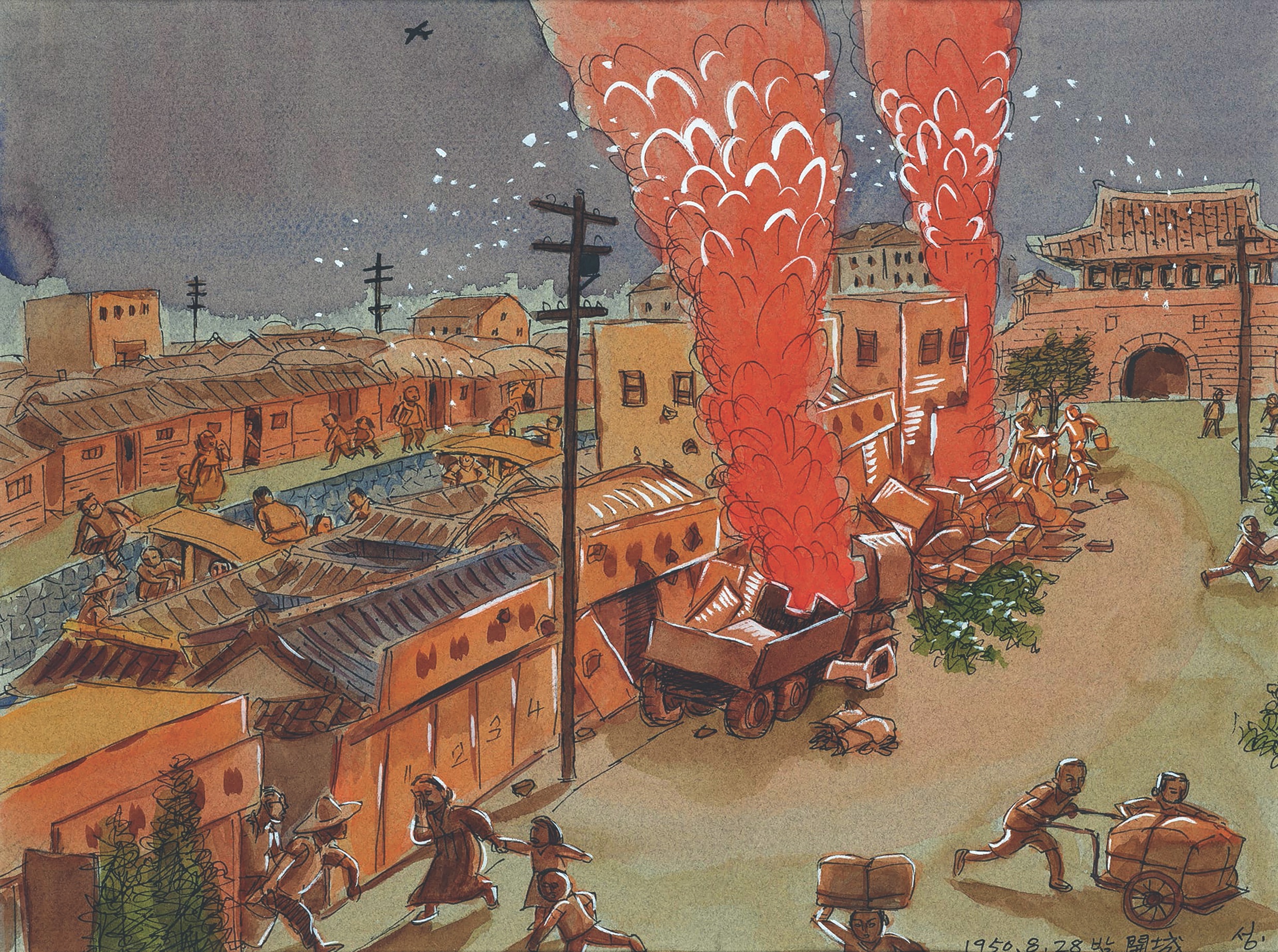

In time Kim would grow bitter about the radio broadcasts because the false reports had misled the residents of the city. “Many people did not flee,” he said, thus becoming easy targets for the invading North Korean forces. For the moment, though, Kim and his friend were sure they were safe. So sure, in fact, that Kim pulled out his art supplies and captured the moment in a pencil and watercolor sketch—the first in a series of extraordinary images in which the young artist recorded his experiences in the opening months of the Korean War, from the North Korean army’s occupation of Seoul that June through the city’s liberation by American soldiers three months later.

When Kim returned to Seoul, he learned that the South Korean army had not been able to hold back the invaders. Kim created vivid portraits of the panicked exodus of Seoul’s residents, carrying everything they owned in bundles—on their heads, on their backs, on bicycles. He watched one South Korean soldier change into civilian clothing, hide his uniform and weapon, and join the panicked evacuation.

Kim, however, chose to stay.

Even before the war, Kim was never without his sketchbook, pencils, and watercolors. As his family was very poor, he helped support them when he was in high school by working as an occasional cartoonist and sketch artist for Korean newspapers, which often could not afford either a photographer or printing equipment capable of legibly printing photographs. Now that most of the civilian population had fled, Kim wandered through Seoul, making sketches and watercolor paintings of his city at war.

The North Korean army overwhelmed Seoul’s badly prepared defenders in three days. Kim watched the victorious army march into the city on June 28. He drew pictures of the occupying army as it moved through mostly empty streets that were still lined with sandbags: detailed sketches of soldiers riding on tanks and jeeps; foot soldiers in tan uniforms, dusty from the road; and tired soldiers hitching a ride on the lumbering oxcarts that made up the army’s supply train.

Over the next few days, Kim recorded the realities of occupied Seoul in muted colors and careful detail. In one drawing, North Korean troops question a man who is pale with terror. In another, a grieving couple covers a lifeless body before they walk away. He drew detailed images of a dying soldier, lying half naked and alone on a straw mat, and of shrouded dead soldiers surrounded by flies. “There were flies everywhere,” Kim later recalled. “Some bodies attracted more than others; maybe the flies liked fresh blood.” The young artist never portrayed the actual moment of violence, only the aftermath of destruction. He had made it his mission to document how the war affected the people of Seoul.

It became increasingly dangerous for Kim to record images of daily life in Seoul because the North Koreans had begun to conscript young men into their army and known artists into their propaganda unit. When Kim went into the streets, he carried a walking stick and faked a limp to make it look as if he were physically unfit to serve in the army. As an unknown high school student, he hoped he would not be forced into service as a propaganda artist.

When food became scarce in Seoul, Kim traveled to the North Korean city of Kaesong, where his aunt ran a boarding house. Once there, he hid in a small room in which his aunt stored blankets. Occasionally, when suspicious North Korean officials would inspect the house, Kim took shelter in the attic or under the kitchen floorboards. To amuse himself while in hiding, he sketched some 200 cartoons, an art form he had begun to experiment with before the war.

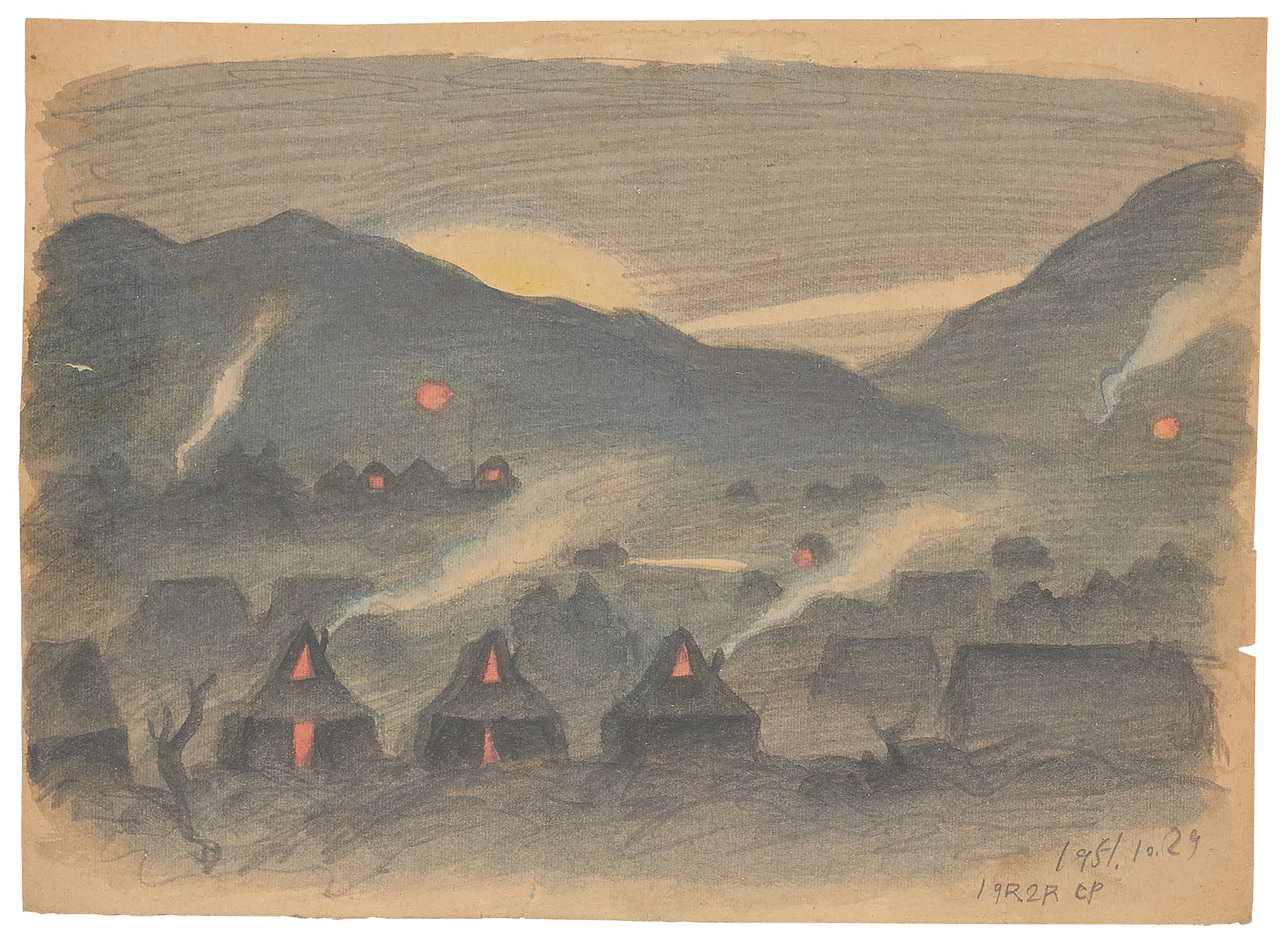

Over time, the city of Kaesong suffered more and more damage from American air raids. When a bomb destroyed Kim’s hiding place, he decided to return to Seoul. On the way there he saw a North Korean army that was very different from the victors who had ridden through the streets of Seoul in late July—and Kim portrayed these beleaguered men in many of the drawings he made on the road. His evocative sketches of young North Korean soldiers on night marches reduce the men to a few quick lines of shadowy blue against darkened backgrounds, alongside detailed images of North Korean jeeps and trucks that had been strafed and abandoned on the side of the road. One picture, done in a cartoon style, captures an incident Kim later described in interviews as indicative of the general panic of the North Korean soldiers. An officer drew his pistol and threatened a farmer whose cart had knocked the officer’s motorcycle off the road. “The North Korean was out of his mind—everybody knows how long it takes a bullock cart to stop or turn,” Kim told an interviewer. “The war was going badly for them.”

Kim made his way back to Seoul a couple of days before U.S. Army forces landed at Incheon in the early morning hours of September 15. He arrived just in time to record the Second Battle of Seoul.

The North Koreans had seized the city with little difficulty, leaving the U.S. Army to face a more determined defense. Some 20,000 North Korean soldiers held the capital. They had dug in and were prepared to fight for every yard of ground. They barricaded the streets with rice bags filled with sand and rubble and defended them with antitank guns and heavy machine guns.

Kim later reported that he heard nonstop artillery and machine-gun fire in Seoul from September 17, when the Americans arrived, until September 28, when they took control of the city. Once again, he ventured into the streets and recorded what he saw. In one detailed scene, U.S. Marines clear a roadblock; dead Korean soldiers lie scattered before their fire. In other drawings, American air strikes are silhouetted over the city against a purple sky, and clouds of smoke mark where bombs hit their targets.

The arrival of the Americans brought new opportunities for Kim Seong-hwan. For three months, the young artist had lived by his wits. After Seoul was reconquered, the South Korean Ministry of Defense hired him as a war artist. He spent time near the front line, attached to South Korea’s 6th Infantry Division, but for the most part, he created informational pamphlets intended for South Koreans.

After the war Kim went on to become Korea’s most famous—and influential—cartoonist. His four-panel cartoon strip featuring Gobau (“Strong Rock”), a character he had conceived while hiding in his aunt’s house during the war, was a powerful mixture of political and social criticism and wry wit. On occasion his commentary was so sharp that government censors periodically interrogated him, but he always managed to stay in print. In 1958 he enraged South Korean president Syngman Rhee with a comic strip that showed a pair of janitors exchanging bows with a colleague as they shuttle buckets of human excrement out of Cheongwadae (the Blue House), the country’s official presidential residence, and he was briefly jailed for his transgression.

From the moment his manhwa (comic, in Korean) debuted in Dong-A Ilbo in 1955, Kim aimed for Old Man Gobau to appeal to adults as well as children—an approach no cartoonist in Korea had ever tried. Another of Kim’s innovations was to draw Gobau without any facial expression and get his point across in some other way. “I thought I should make him significantly different from other cartoon characters,” Kim once explained to an interviewer, “and I decided to express Gobau’s mood or psychological state with one hair instead of an expression.”

In 2000, after producing 14,139 four-panel episodes of Old Man Gobau), Kim decided to retire. “Wouldn’t it make sense to finish it on the 50th anniversary?” he explained. South Korea’s national postal service marked the occasion by issuing a stamp that showing Gobau’s evolution over the past five decades, and the following year the Guinness Book of Korea recognized Kim’s creation as the longest running comic strip in the country’s history.

In retirement, Kim turned to Jangsaeng-do, a traditional form of Korean painting that emphasizes such symbols of longevity as the sun, mountains, clouds, pine trees, and turtles. He died in 2019 at age 86. MHQ

Pamela D. Toler, who writes about history and the arts, is the author of several books, including, most recently, Women Warriors: An Unexpected History (Beacon Press, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Sketching a War’s Toll

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!