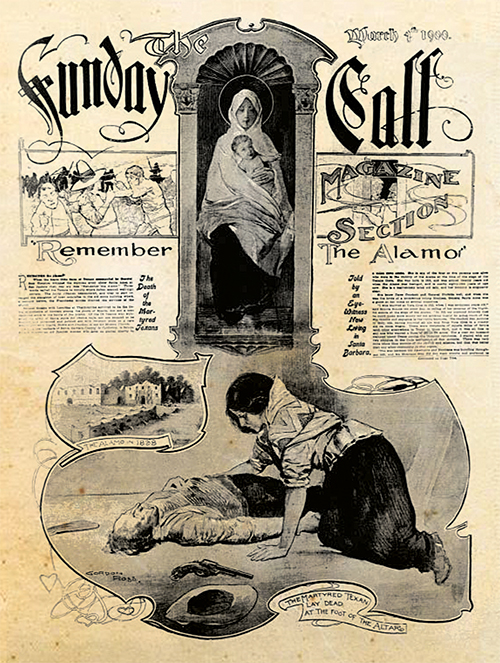

In the collective memory of the Alamo’s last stand saga there is perhaps no image more poignant or powerful than that of the Texian dead being consumed on March 6, 1836, by massive funeral pyres. Plumes of black smoke spiraled from the pyres as flames leapt skyward in symphony with the crackling of branches and kindling.

The lifeless bodies of David Crockett, James Bowie, William Barret Travis and the other Alamo defenders were stacked between layers of wood before being set ablaze. “Fragments of flesh, bones and charred wood and ashes revealed it in all of its terrible truth,” recalled Pablo Diaz, who as a young man had been forced to gather wood that day. “Grease that had exuded from the bodies saturated the earth for several feet beyond the ashes and smoldering mesquite fagots. The odor was more sickening than that from the corpses in the river. I turned my head aside and left the place in shame.”

Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna had ordered the enemy dead burned and left unburied. Regarded by Texian rebels as sacrilege, his ruthless action only served to highlight the sacrifice the Alamo defenders had made toward the revolutionary cause, ensuring their martyrdom. Angered and inspired, Texians vowed to remember.

So would the nation.

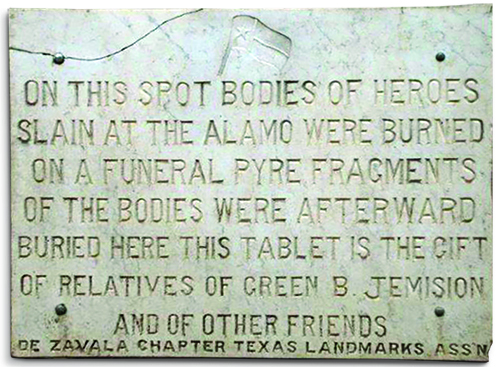

In the aftermath of the Texas Revolution travelers to San Antonio were drawn to the site of the celebrated Battle of the Alamo. Amid the ruins local guides would point out the spot where Crockett supposedly fell or the room where Mexican soldiers slew Bowie in his sickbed. Some luridly claimed Bowie’s bloodstains remained visible on the wall. Invariably, visitors asked about the final resting place of the Alamo dead, and locals would motion toward a peach orchard a few hundred yards from the mission fort. There, nearly a year after the battle, local authorities had the ashes of the Texian defenders scooped into a lone coffin and interred with military honors. In 1868 Reuben M. Potter, whose retrospective article “The Fall of the Alamo” was published in that year’s Texas Almanac, noted the burial site “is now densely built over, and its identity is irrevocably lost. This is too sad for comment.”

In truth, the fate of the cremated remains is far sadder. In February 1837 Colonel Juan N. Seguín of the Army of the Republic of Texas, who’d left the Alamo amid the siege as a courier, led the procession to inter the ashes of his comrades. In 1889 he recalled having had the ashes buried within San Antonio’s San Fernando Cathedral, “in front of the altar railings, but very near the altar steps.” José María Rodriguez, who witnessed the storming of the Alamo as a child, later expressed doubt the ashes had been buried inside the sanctuary without the common knowledge of his fellow parishioners, though a marble sarcophagus just inside the entrance of the present-day cathedral supposedly holds those ashes. Finally, there is a 1906 account from city clerk August Biesenbach, who told San Antonio Express reporter Charles Merritt Barnes that years after the battle “some of the fragments of heads, skulls, arms and hands had been removed and buried” at the Odd Fellows Cemetery, about a mile east of the Alamo.

The discovery of various skeletons, skulls and bone fragments over the intervening 185 years indicate the disposal of the Texian dead wasn’t as neat and tidy as history books generally portray

Thus the true resting place of the Alamo dead may forever be shrouded in mystery. For starters, not all of the defenders’ remains wound up in Santa Anna’s funeral pyres—a fact generally unknown beyond a small circle of Alamo scholars and enthusiasts. The discovery of various skeletons, skulls and bone fragments over the intervening 185 years indicate the disposal of the Texian dead wasn’t as neat and tidy as history books generally portray. In a March 6, 1836, victory dispatch Santa Anna noted, “More than 600 corpses of the foreigners were buried in the ditches and entrenchments”—his bloated estimate of Texian dead as absurd as his burial claim. No such mass grave has ever been found. Yet the suggestion fatigued Mexican soldiers may have rolled some defenders’ bodies into ditches and hastily covered them with dirt is not absurd. Further complicating the search for answers is the fact that some of the remains unearthed on the battleground date from the earlier Spanish mission period.

More recent discoveries of human remains at the Alamo extend hope for a more complete accounting of those buried there, perhaps even revealing defenders whose corpses were spared the flames. The discoveries are tied to a $450 million renovation of Alamo Plaza, and the details are tantalizing. In an internal email dated Dec. 4, 2019, archaeologist Kristi Miller Nichols noted the discovery of the remains of three people during excavation work within the Alamo chapel. Among the remains were two femur bones between stained ground amid “an alignment of nails” and wood fragments. “We may have uncovered remnants of a possible coffin,” Nichols wrote. A follow-up email from the archaeologist, dated Jan. 23, 2020, revealed her team had unearthed “a concentration of human bones” during a separate exploratory dig inside the chapel.

Researchers are unclear whose remains they are or when they perished, and the Texas General Land Office—the present-day caretaker of the historic site—has yet to approve DNA testing. The issue is controversial. The Alamo Defenders Descendants Association filed a lawsuit in state district court, demanding the remains be tested to determine whether the bones belong to members of the Alamo garrison. The group has even started a DNA database of its members. But other cultural groups are opposed to DNA testing on religious grounds.

That any of the remains may be those of an Alamo defender is hardly far-fetched. In 1846, with the Mexican War raging, Captain James Harvey Ralston moved to transform the ruins of the chapel and adjacent long barrack into a depot for the U.S. Army Quartermaster Department. The assistant quartermaster’s staff included young Sergeant Edward Everett, to whom Ralston had extended a clerkship while Everett recovered from a pistol wound. A talented artist and draftsman, Everett was assigned to collect information on the history and customs of the area, during which he rendered brilliant watercolors of the San Antonio missions that are on display at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Everett’s Alamo watercolors represent some of the earliest artistic depictions of the battle-scarred chapel, including a rear view of its roofless interior with rocks strewn about the dirt floor and weeds growing atop its walls. He left an equally important written account of what he observed at the Alamo in a 1906 manuscript titled “A Narrative of Military Experience in Several Capacities.”

“The church seemed to have been the last stronghold,” Everett wrote, “and amidst the debris of its stone roof, when subsequently cleared away, were found parts of skeletons, copper balls and other articles, mementos of the siege.” The artist noted the reverence with which he and fellow soldiers regarded the Alamo. “We respected it as a historical relic—and as such its characteristics were not marred by us.”

Which begs the question, What happened to the skeletal remains Everett mentioned?

Everett’s renderings of the Alamo ruins support eyewitness accounts of the battle and its aftermath. For example, San Antonio resident Eulalia Yorba recalled being pressed into service to tend to wounded Mexican soldiers. “The stones in the church wall were spotted with blood,” she said, “the doors were splintered and battered in.” On entering the chapel, she maneuvered around pools of blood and heaps of dead Texians, one of whom seemed to stare at her wildly with open eyes. “The woodwork all about us was riddled and splintered by lead balls, and what was left of the old altar at the rear of the church was cut and slashed by cannon ball and bullets.”

In a journal entry dated May 24, 1836, Dr. J.H. Bernard, a Texian captive who’d been spared execution at Goliad, documented the Mexican army’s departure from San Antonio. The doctor said the soldiers first fired the chapel interior, dominated by a large, wooden artillery platform extending from the great front doors to the top of the rear wall. The fire consumed all but the exterior masonry walls, burying any Texian dead beneath a blanket of blackened debris.

‘Deep down in the debris,’ author William Corner wrote, ‘were found two or three skeletons that had evidently been hastily covered with rubbish after the fall, for with them were found fur caps and buckskin trappings, undoubted relics of the ever memorable last stand’

The Alamo sat in ruins until Captain Ralston’s intervention in 1846. By then the presence of defenders’ skeletal remains within the chapel was common knowledge in San Antonio. In his 1890 book San Antonio de Béxar: A Guide and History author William Corner recalled one specific discovery of remains that echoes the descriptions of Everett and Bernard. “Deep down in the debris,” Corner wrote, “were found two or three skeletons that had evidently been hastily covered with rubbish after the fall, for with them were found fur caps and buckskin trappings, undoubted relics of the ever memorable last stand.” He dates the discovery to the 1849–54 tenure of Major Edwin Burr Babbitt of the Quartermaster Corps, who oversaw the construction of a wooden roof on the chapel, as well as a second floor and the iconic hump atop the Alamo facade.

Whether Corner was noting a separate discovery of skeletal remains by Babbitt or mistakenly referring to Everett’s earlier find is unknown. Regardless, what became of those Alamo skeletons in buckskin? In all probability the military buried them out of respect. If so, were they buried inside the chapel where found? Were they among the remains unearthed by archaeologists in December 2019 and January 2020? DNA tests may provide the answers.

Meanwhile, further evidence strongly suggests other Alamo defenders may have escaped Santa Anna’s funeral pyres. In March 1979 archaeologists James Ivey and Anne Fox led a dig where the compound’s north wall once stood. Amid what they identified as the fill of an 1836-era defensive trench they unearthed the partial skull of a possible male of unknown ethnicity between the ages of 17 and 23. Marking it were four cuts possibly inflicted by a knife or saber. “As far as we can tell,” Fox and Ivey concluded, “the skull is that of a participant in the Battle of the Alamo.”

The skull resides at the Center for Archaeological Research on the University of Texas’ San Antonio campus. It has yet to undergo DNA testing. In March 2014 Amanda Danning, a noted forensic sculptor who performs facial reconstructions on historic skulls, received special permission to study the Alamo skull. The artist is convinced she found at least one other clue as to the identity of the deceased. “In the first place, the eyebrows, the nose and the cheekbones are all broken off,” Danning notes, “so what you’re looking at is the overall shape of the cranial bowl and the thickness of the skull. The overall markers and indicators suggest that it was European. I didn’t see any kind of indicators that it was Native American or Mexican, but I’m only looking at the back of the skull.” If Danning’s analysis is correct, that would rule out any Mexican soldiers or Indian converts from the mission period.

Among those buried in the mission compound before or during the 13-day siege may be men who succumbed to wounds suffered during the December 1835 Siege of Béxar. A number of Texians known to have died at the Alamo are listed among the wounded on a muster roll after that December engagement. Several are labeled as “severely wounded,” while defender James Nowlan is listed as “dangerously wounded.” Whether any of these men survived until the March 6, 1836, final assault is unknown. The odds were certainly not in their favor. In a February 13 letter to Texas Governor Henry Smith, Alamo surgeon Amos Pollard spelled out the garrison’s dire medical situation: “It is my duty to inform you that my department is nearly destitute of medicine, and in the event of a siege I can be of very little use to the sick.”

Twenty-two days later Pollard perished with the rest of the garrison. Chances are his lifeless body—like those of most of his fellow defenders—was consigned to the flames of a funeral pyre. And while the hallowed grounds of the Alamo may continue to yield archaeological clues, the fates of many who died in its defense 185 years ago will assuredly remain a mystery. Regardless, there will always be the terrible glory of sacrifice to remember in those flames.

“Death united in one place both friends and enemies,” recalled Mexican Colonel José Enrique de la Peña of that hellish day, adding, “within a few hours a funeral pyre rendered into ashes those men who moments before had been so brave that in a blind fury they had unselfishly offered their lives and had met their ends in combat.”

Even their enemies would remember. WW

Ron J. Jackson Jr. is a regular Wild West contributor and the award-winning author of Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend (co-authored by Lee Spencer White), Alamo Survivors (also co-authored by Lee Spencer White) and Alamo Legacy: Alamo Descendants Remember the Alamo. For further reading he also recommends The Alamo Reader, edited by Todd Hansen, and Alamo Defenders, by Bill Groneman. This article was published in the February 2021 issue of Wild West.