Two Communist superpowers traded shots over a tiny riverine island in a clash with international implications

On Oct. 13, 1969, unknown to the American public, President Richard M. Nixon put the nation’s nuclear forces on high alert. For more than two weeks various unified combatant commands raised their readiness levels, while Navy surface ships and nuclear submarines stepped up activities worldwide. However, unlike the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, this Cold War military operation was shrouded in secrecy—so much so that not even the generals of the commands themselves were briefed on its exact purpose. A prominent theory among historians is that the alert was in response to a potential Soviet nuclear strike on China.

The Chinese had been openly preparing for just such a possibility. That fall Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Mao Zedong had officially placed his country on a war footing. The national economy was mobilized, factories were converted to military use and evacuated into mountains, and Beijing scrambled to construct a massive underground city to shelter from nuclear attack. On October 17 the CCP placed all People’s Liberation Army (PLA) units on emergency wartime condition—the Chinese equivalent of the Pentagon’s DEFCON 1.

Seven years after the Cuban standoff the world was once again on the verge of nuclear war. This time, however, the world’s leading communist powers were pitted against each other in a conflict that traces its origins to a border clash six months earlier on a tiny riverine island in a remote corner of northeast Asia.

Zhenbao (Chinese for “Rare Treasure Island”) bisects the Ussuri River, which marks the border between northeast China and the Russian Far East. The vast surrounding landscape, stretching from the Amur River north to the Stanovoy Range, is a region the Chinese traditionally referred to as Outer Manchuria. By the 19th century, as the declining Qing dynasty was beleaguered by internal rebellion and the Opium Wars, imperial Russia encouraged settlers to encroach on the region. In the 1860 Convention of Peking, at the close of the Second Opium War, a defeated and humiliated China ceded Outer Manchuria to Russia, shifting the Sino-Russian border south along the Amur and Ussuri Rivers. Per international custom river boundaries are demarcated along the median of the main channel. Accordingly, Zhenbao, which lies on the Chinese side of the Ussuri, still belonged to China, but the Russians took control of it anyway, eventually naming it Damansky after a noted railway engineer.

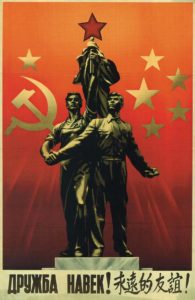

Over the following century ownership of the island remained a nonissue. With the 1949 Maoist takeover of China the inconvenient history of Russian imperialism was ignored in favor of communist solidarity. Chinese and Soviet patrols occasionally bumped into one another on the island. While officers delivered each side’s official protest, soldiers exchanged cigarettes and communist memorabilia. After all, at not even one-third of a square mile the wetland of Zhenbao was relatively insignificant. Hundreds of almost identical islets dot the Ussuri.

By the early 1960s, however, relations between China and the Soviet Union began to deteriorate. As the nations diverged on their interpretations of Marxist-Leninist doctrine and vied for leadership in the communist world, the more than 4,500 miles of Sino-Soviet border—long stretches of which hadn’t been properly demarcated since the 19th century—came under increased scrutiny. Chairman Mao and Nikita Khrushchev, first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, engaged in virulent arguments over the history of Russian imperialism and China’s “unequal treaties,” thwarting attempts at diplomatic resolution.

By the second half of the decade—as Soviet First Secretary Leonid Brezhnev adopted a more hard-line stance on foreign policy, and the Cultural Revolution ravaged China—violence broke out along the Sino-Soviet border. Chinese fishing boats and Soviet vessels rammed each other on the Amur and Ussuri rivers in summer. In winter zealous Chinese Red Guards marched across the frozen river, Little Red Books in hand, to argue and scuffle with Soviet soldiers. There were no more friendly exchanges of gifts when Chinese and Soviet patrols bumped into each other. Instead, soldiers brawled with rifle butts, wooden bats and other weapons. Troops on both sides were under strict orders not to fire first.

Behind the medieval melee on ice, however, each nation was positioning more modern and destructive weaponry. In 1961 a dozen Soviet divisions deployed along the border; by 1969 there were 22. China reorganized its defensive strategy in 1965, shifting its primary military focus from the southeast coast to its northern border. Nuclear weapons were also on the table. In 1964 China detonated its first atomic bomb, becoming the world’s fifth nuclear power. Within three years Beijing also detonated its first hydrogen bomb. In 1967 the Soviet Union constructed its first nuclear missile base in the Transbaikal Military District, due north of the Mongolian People’s Republic, with which it had signed a mutual assistance treaty. A year later Moscow moved missiles and troops into Mongolia. Neither the Soviet Union nor China planned on starting a war, but each was afraid the other might. The Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 only heightened the Chinese leadership’s concerns, cementing Mao’s resolve.

On Jan. 5, 1968, a skirmish erupted between a Soviet patrol and Chinese fishermen on an island a few miles upstream from Zhenbao. During the confrontation a Soviet BTR-60 armored personnel carrier ran over several fishermen. When an angered Chinese mob swarmed the vehicle, a panicked soldier inside opened fire. Four Chinese civilians were killed in the incident, and the news soon reached Beijing. The Central Military Commission advised the Shenyang Military Region to mount an appropriate retaliation. The regional commanders in turn formed a commando squad of elite personnel from garrison units and ordered it to ambush the next Soviet patrol. In a 2014 interview commando Wang Guoxiang, then political officer of the Red One Company of the 217th Infantry Regiment of the PLA’s 73rd Division, recalled lying in freezing snow for seven straight days and nights. The Russians never returned.

Whether due to Soviet intelligence or simple serendipity, a battle was averted. The same cannot be said for Zhenbao a year later.

Spring came late in 1969. The morning of March 2 was as brisk as any Siberian winter dawn, with temps hovering around minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit. Soviet forces in the Far East were busy conducting a military exercise against an imagined Chinese invasion. As part of the exercise all Soviet units pulled back 30 miles from the border, leaving only token garrisons at the outposts. Among those left behind was Junior Sergeant Yuri Babansky, who found himself staring blankly across the snow-covered Ussuri from the 2nd Nizhne-Mikhailovka border post. Around 10:20 a.m. Soviet sentries spotted a Chinese patrol of some 30 soldiers in white winter camouflage marching openly across the frozen river toward Zhenbao. Treating it as a routine affair, the 32 border guards at Nizhne-Mikhailovka boarded a BTR-60 and two GAZ light trucks and went to greet the Chinese. Once on the island post commander Senior Lieutenant Ivan Strelnikov sent Babansky with some two dozen men to confront the Chinese patrol, while he took a half dozen soldiers onto the river in a flanking maneuver. Babansky led his men to the edge of an open snowfield.

Facing him across the field was Sun Yuguo, commander of the local PLA border post. The men might have met before, perhaps in one of the many wild brawls on the ice. But Sun knew the time for brawling had passed, for in the snow just yards from the unsuspecting Soviets lay a company of Chinese commandos, ready to spring an ambush. The commandos were not regular border guards but elite recon troops selected from three army corps in the Shenyang Military Region. Sun’s job as post commander was to lure the Soviets into the commandos’ trap. He had successfully accomplished his mission.

Not 20 feet from Babansky, Wang once again found himself lying in freezing snow. He and his Red One Company had secretly moved onto the island the previous night, dug shell scrapes and laid telephone lines to shore. The commandos had lain motionless the entire night. To maintain silence, each man had been given a packet of cough medicine. Having achieved surprise, they waited for Sun’s signal to jump up and fire their Type 56 assault rifles, variants of the Soviet AK-47.

That signal came in one crisp shot that echoed across the island. Strelnikov’s seven-man squad had run into a much larger group of Chinese on the frozen river, and as Babansky turned to see what had happened, overlapping bursts of automatic fire erupted around him. At such close quarters a half dozen men from both sides dropped within the first seconds of the mad exchange. As he ducked for cover, Babansky could only watch as the Chinese mowed down Strelnikov’s detachment. He assumed command of the surviving troops.

An ambush on Zhenbao had long been in the works within the PLA. Heilongjiang Provincial Military District officials had approved a draft proposal on January 25 and sent it up to the PLA General Staff Department and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was ultimately approved by the highest decision-making circle in Beijing, presumably including Mao, who oversaw all border affairs with the Soviet Union. The PLA then mobilized and transported three reconnaissance companies to the Zhenbao area to train for the operation. On the morning of the ambush senior PLA commanders were gathered in Beijing in advance of the CCP’s Ninth National Congress. Technicians set up a direct telephone connection in a suite of the Jingxi Hotel so Chen Xilian, commander of the Shenyang Military Region, could receive live updates from Zhenbao. The deputy minister of foreign affairs was also present, keeping track of international diplomatic activities and reporting directly to Premier Zhou Enlai, who reported to Mao.

That morning their Soviet counterparts were also making phone calls, albeit far more frantic and confused. Around noon Colonel Demokrat Leonov of the 57th Border Detachment, headquartered some 40 miles south of Zhenbao in Iman, was about to report his unit’s successful completion of the military exercise when news arrived from Nizhne-Mikhailovka. Within an hour Colonel General Oleg Losik, commander of the Far Eastern Military District, was on the phone with a bewildered Alexei Kosygin, chairman of the Soviet Council of Ministers.

Russian political leaders had been caught wholly off guard by the Chinese attack. Brezhnev was overseas, while the Kremlin was preoccupied with continuing fallout from the previous year’s invasion of Czechoslovakia as well as a forthcoming summit with the United States—activities requiring a softer touch on the international stage. After much deliberation the only instruction Moscow could give Losik was to defend the national boundary but prevent a large-scale military conflict. The politically seasoned general understood the seemingly paradoxical order. The battle was to be limited to border troops; there would be no Soviet army reinforcements.

Indeed, the only reinforcements that came to Babansky’s aid that day were two dozen men in a BTR-60 from the neighboring 1st Kulebyakiny Sopki border post, under Senior Lieutenant Vitaly Bubenin. After almost two hours of fighting Leonov finally gave Babansky the order to retreat. By that point only a handful of his 31 comrades remained standing. To cover the decimated patrol’s withdrawal, Bubenin drove his BTR onto the 60-yard-wide Chinese side of the frozen Ussuri to draw fire. When RPG fire knocked out his vehicle, he and three of his men jumped into the 2nd Nizhne-Mikhailovka’s abandoned BTR and continued the flanking assault, madly firing the armored vehicle’s mounted machine guns. Bubenin somehow managed to take out the enemy command post, and the surviving Chinese retreated.

The March 2 engagement did not mark the end of conflict. Though both sides withdrew from Zhenbao itself, each moved up reinforcements. While awaiting Moscow’s approval to commit regular army units, Colonel General Losik deployed the 135th Motor Rifle Division a few miles behind the Ussuri. Its arsenal of equipment included the T-62 tank and the then classified BM-21 “Grad” multiple rocket launcher. From his command post in a Beijing hotel room Chen also raised the stakes, sending up additional infantry and artillery regiments from the PLA’s 67th Division.

Before dawn on March 15 Chinese and Soviet patrols again deployed to the island from their respective riverbanks, sparking a new round of fighting far larger in scale and especially brutal. Soviet infantry pushed forward behind a screen of BTRs, while the Chinese countered with RPGs and 75 mm recoilless rifles. Around noon Colonel Leonov of the 57th Border Detachment finally received reinforcement in the form of four T-62 tanks hastily transferred by Soviet staff officers just hours earlier. As the drivers were unfamiliar with the area, Leonov climbed into the lead tank to direct the attack. Instead of advancing to the island, the tank column circled around it on the frozen river and approached the Chinese bank. The flanking maneuver was thwarted when the colonel’s tank struck a mine and was de-tracked. Realizing the Chinese had mined the very river ice, Leonov ordered the other tanks to withdraw. As the colonel himself abandoned his immobilized T-62, he was struck and killed by Chinese sniper fire, becoming the highest-ranking casualty of the conflict.

By that afternoon the situation was dire on both sides. In his district headquarters Losik still hopelessly waited for Moscow’s order to commit army units. Meanwhile, across the river Chen’s infantrymen had reached their limit. Facing repeated Soviet motorized assaults supported by Mi-4 helicopters, the Chinese were decidedly outmatched in terms of heavy equipment. Wang, who on his return visit to the island was commanding a reinforced platoon, recalled watching one of his soldiers, bare-chested in the minus 30 degree cold, firing one RPG after another at the Soviet armored cars. By the time the platoon finally pulled back, the man was deaf in one ear.

At 5 p.m. sharp 122 mm howitzers and Grad rocket launchers of the Soviet 135th opened fire on the Chinese positions. To Wang the low-velocity howitzer shells and rockets resembled a dense flock of crows rising over the horizon. The shells made a low-pitched, droning sound as they approached, but Wang never heard the explosions, as the hellish barrage temporarily deafened him. After a solid 10 minutes of intense bombardment two companies of Soviet army tanks and infantry surged onto the island. Surviving Chinese strongpoints mounted a fierce resistance, but by 6 p.m. most PLA troops had pulled out of Zhenbao. As evening set in, Soviet troops also withdrew. After more than nine hours of deafening battle, an eerie silence settled over the tiny island now littered with shell holes, wreckage and bodies.

Sporadic firefights and artillery duels broke out again on March 17, mainly in the vicinity of Leonov’s abandoned T-62, which the Chinese ultimately captured. But no more major engagements took place on Zhenbao. As the conflict had already reached the regular army level, and nuclear forces across north Asia were on alert, neither the Soviet Union nor China was willing to risk further escalation. Thus the border situation returned to status quo, and Zhenbao remained a piece on the political chessboard.

As the Kremlin never contacted the Far East on March 15, Losik had unilaterally decided to employ regular troops and the army’s top-secret Grad rocket launchers. He shouldered all responsibility for his actions. Fortunately, the battle had turned in his favor. Two months after the incident his superiors transferred Losik from the Far Eastern Military District to Moscow to head the Malinovsky Military Armored Forces Academy. Promoted to marshal of armored troops in 1975, he retired from the Soviet army in 1992 and died at the venerable age of 96 in 2012. Leonov and Lieutenants Babansky and Bubenin were recognized as Heroes of the Soviet Union for their actions, as was Lieutenant Strelnikov in a posthumous award. A decade later then General Bubenin led his Alpha Group special forces into Afghanistan.

Less than a month after having directed the battle from his Beijing hotel, despite the outcome, Chen was inducted into the Politburo, China’s highest policy-making authority, in the CCP’s Ninth National Congress. He continued to climb the CCP political ladder until falling out of favor in the 1980s and being forced to retire. During the same CCP congress Sun, the PLA border post commander, was enthusiastically greeted by Mao and commended as a “combat hero.” Among the hundreds of others left out of the spotlight, Wang grew disillusioned with the CCP political propaganda surrounding the Zhenbao fight and was quietly discharged in 1979.

Zhenbao itself, that tiny, formerly insignificant dot on the Ussuri, was officially given to China as part of the 1991 Sino-Soviet Border Agreement. Today a modest Chinese memorial park marks the battleground.

A half century later details of the Zhenbao/Damansky Island incident remain shrouded in political rhetoric and communist propaganda. Russian media define the event as the first time since World War II its territory was subject to foreign invasion, while Chinese textbooks refer to it as a “self-defense counterattack.” Each side claims the other fired first. To date there is no consensus on many key details, including casualties. According to self-reported numbers, from March 2–17 the Chinese suffered an improbable 29 dead, 64 wounded and one missing, while the Soviets lost 58 dead and 94 wounded.

Though limited in scope, the clash carried disproportionate historical significance. It was a watershed moment that displayed to the world—most important the United States—the extent of the Sino-Soviet split. Stuck in the quagmire of Vietnam, the Nixon administration looked to China as a potential ally against Soviet hegemony in Asia. Recovering from the brink of total war and faced with the Soviet nuclear threat, Beijing was willing to engage in a Sino–American rapprochement. Neither Mao nor Brezhnev—let alone the soldiers who had exchanged fire across the border—would have imagined the 1969 clash over a tiny island would be a catalyst for Nixon’s Air Force One to land in Beijing three years later. MH

Jesse Du is a history writer specializing in modern East Asia. For further reading he recommends The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World, by Lorenz M. Lüthi, and Beyond the Steppe Frontier: A History of the Sino-Russian Border, by Sören Urbanksy.

This article appeared in the July 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: